European Studies at Maastricht University: Problem-Based, Interdisciplinary, and International

This is part of our Campus Spotlight on Maastricht University.

Between Belgium and Germany on the most Southern border of the Netherlands is situated the historic city of Maastricht. Its citizens speak several languages by default, and the international atmosphere is a permanent feature in the numerous cozy cafés in the city-center. While Maastricht is the oldest town in the Netherlands, it hosts the youngest Dutch university. After the demise of the mining industry in the 1970s, the government of the Netherlands suggested the establishment of a University as a route to further regional development in this previously mining town. And so was Maastricht University founded in 1976. It rapidly built a reputation for being an innovative higher-educational center employing the didactic concept of Problem-Based Learning (PBL), and established remarkably quickly an academic tradition that is currently ranked sixth among the universities under fifty.[1]

European studies at Maastricht University

In February 1992, the city of Maastricht hosted the signature of the founding treaty of the European Union—the Maastricht Treaty. Moreover, Maastricht is a relatively short drive to the European institutions in Brussels—close enough to observe them in detail, yet at a sufficient distance to study them critically. Against this background, it is not surprising that Maastricht University (UM) hosts the biggest bachelor program in European studies in the Netherlands. Launched in 2002, the three-year degree welcomes annually about 300 students from all over the globe, with as many as eighty percent of learners coming from abroad (forty different nationalities). Germans (32 percent), Dutch (20 percent), and Belgians (14 percent) comprise the largest groups of students, but Eastern and Southern Europe are well-represented as well. This allows for genuine cultural exchange and a productive mix of perspectives for the sake of comprehensive analysis and understanding of contemporary European phenomena. The culturally diverse student body forms a truly international classroom, and allows for an excellent simulation of decision-making under heterogeneous conditions. In addition, students are exposed to various cultural, legal, economic, and political norms as materialized in the various viewpoints expressed during the problem-driven tutorial discussions. This confronts them with the intricacies of Europe, and they achieve deep understanding based on a direct, first-hand experience.

The Bachelor of Arts in European Studies (BA ES) at Maastricht University aims to form critical analysts for the unique political, legal, historic, economic, and cultural space that Europe represents today. The program trains students to examine and understand complex contemporary European processes such as: economic crises in the context of interdependency, cross-border migration, the rise of populism, or international security dilemmas in their internal and external contexts. These are phenomena that require an interdisciplinary platform of analysis, and this is exactly what the Maastricht ES bachelor has cultivated for nearly twenty years to date.

The program is an intellectual mix of humanities and social sciences reflecting the diverse faculty coming from the disciplines of philosophy, history, law, sociology, economics and political science. Teaching is structured so that a combination of members from different departments contribute to each educational course (typically eight weeks in length). More than sixty percent of the staff come from abroad. Such diversity creates an atmosphere that strengthens the international orientation, and ensures case studies from all corners of Europe are examined within the program. This interaction across national and disciplinary boundaries is at the heart of the ES didactic vision and one of its core strengths (as regularly confirmed by alumni).

Problem-based learning

The BA ES, like all other programs at Maastricht University (UM), follows the didactic method of Problem-Based Learning (PBL), a teaching method grounded in four guiding principles, according to which learning is approached as a constructive, collaborative, self-directed, and contextual process. Characteristic of the PBL approach is that it encourages students to take charge of their own learning process. It places emphasis on dialogue and collaboration, which are facilitated through the small-scale educational set-up (e.g. tutorial groups of twelve to fifteen participants). Lectures complement the tutorial group discussions, usually by clarifying complex concepts and theories, or placing processes in context and building links between sub-themes within the larger problem that is analyzed.

The UM teaching philosophy rests on the conviction that learning is a collaborative process. More than that, with PBL, students are in the driving seat of the educational process, and that means that they have autonomy in how they approach the main problem that is posed in front of them in the course. Furthermore, they are constantly challenged by the didactic organization of course assignments to search for answers to the main problem by defining learning goals, and answering them (which in turn leads to new learning goals). By activating prior knowledge, PBL invites them to draw links with other courses and their own background, as well as with societal developments.

The bachelor in European studies curriculum

Having functioned successfully for fifteen years, the BA ES curriculum is currently undergoing a comprehensive reform. After careful preparation (which started in 2017) and adaptation of the various courses within interdisciplinary course planning groups, the renewed curriculum has been phased-in starting from September 2020. The educational vision behind the new courses maintains the key features that have proven to be successful throughout the years, while enhancing the (analytical) links between the different courses. In practice, this means that the problem-based learning didactics and the interdisciplinary approach remain at the heart of each course, but next to that was introduced an explicit theoretical and conceptual toolbox geared toward answering in a systematic way the main course problem. Each course is devoted to an overarching question—or main problem/social challenge—that contemporary Europe faces. For example:

- How are political communities formed, organized, and maintained in Europe?

- How to conduct economic integration and to reap the benefits of a single market under conditions of cultural and political diversity and economic disparities?

- How to establish and sustain legal order beyond the nation-state?

- What keeps political regimes in power and under which conditions do they decline?

- How effective and democratic is decision-making within international organizations?

The BA ES aims to train students to approach such questions as researchers, whereby they need to reach out to various branches of literature in order to answer them. The exact mix and proportion is for the students to establish, driven by their interests and inevitable biases and predispositions toward, for example, history, political science, or law.

This teaching philosophy was first put into practice by forming interdisciplinary teams (course planning groups), which were charged with defining each overarching course question/problem. Secondly, the team had to break each key course question into sub-questions or problems, and on that basis create weekly course assignments (two assignments per week for the duration of seven weeks, i.e. each course contains fourteen sub-problems). Thirdly, each course planning group had to make two sets of choices about:

- The scope of the course—the covered phenomena, cases studies, or empirical observations that need to be understood and interpreted. These choices were made based on the defined sub-problems. For example, in an assignment about intergovernmental conferences and the political origins of the founding treaties, a case study pertains to the negotiations of the Maastricht treaty.

- The analytical toolbox applied in the course—the concepts, models, theories, and analytical frameworks that ensure the systematic digestion of the selected phenomena, cases, events, and observations. For example, in an assignment about intergovernmental conferences and the political origins of the founding treaties, liberal intergovernmentalism and neofunctionalism are studied as theoretical lenses.

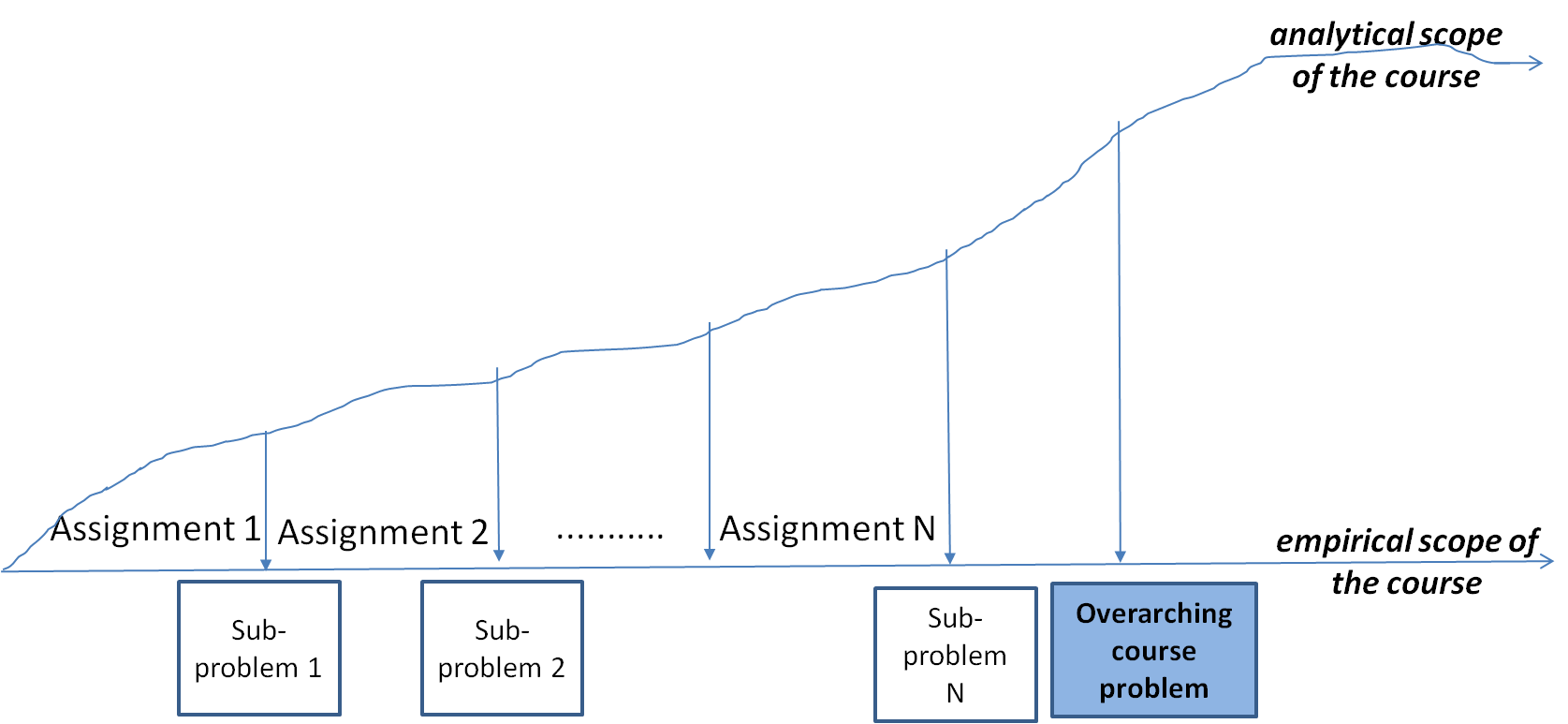

In a nutshell, course designers had to carefully select the most adequate examples of (historical) developments that illustrate the chosen central problem and its sub-problems, but also propose ways to study them, i.e. to make a choice of interpretative schemes, models, and theoretical mechanisms that provide a lens to the chosen sub-problem for the assignments (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Course organization under problem-based learning

The two streams should have a synergic relation at the level of sub-themes covered in each assignment. Ideally, the analytical complexity grows with each assignment—students are introduced to ever more complex concepts, theories, models, and methods from various disciplines that provide an answer to the overarching problem. At the end of the course, students have acquired a comprehensive understanding of the main problem, and are able to apply analytical tools to unravel the sub-problems and further learn about this or related subjects/topics.

Course example: EU Law

In the course on EU Law, the overarching interdisciplinary question serving as the main course problem is: “How to organize and sustain a legal order beyond the state?” This main problem is composed of legal, political, socio-cultural, and public administration sub-questions such as:

- How is consensus reached between political leaders of various European states?

- What is the dynamics of intergovernmental conferences that transform political consensus into legal treaty provisions?

- How are treaties organized and how do they serve as primary legislative framework that conditions all secondary legislative acts?

- What are secondary legislative acts and how are they adopted in the EU system of governance?

- What are the possible procedures and institutional arrangements that sanction deferring member states, and how to minimize political bias in such decisions?

- What role do cultural norms play in shaping judicial traditions in Europe (e.g. in implementing EU law)?

Each of these sub-problems forms the basis for one course assignment and is linked to suggested literature. After Year 1, students are especially encouraged to find additional literature by themselves. All courses follow this pattern, forming a coherent curriculum.

The student journey goes through three phases. The first—fundamental—is common for all ES students and introduces the key disciplines in the program, as well as the basics of social scientific theories and methods. The second—elective—provides further in-depth knowledge in one of the disciplines that form the core of the ES program: international relations, law, history, cultural studies, political science, and economics. In the final phase—graduation—students choose among three graduation options that analyze topical contemporary European challenges.

Following the course design outlined above and a unified syllabus structure, the BA ES offers simultaneously a broad interdisciplinary enquiry of Europe (which students can steer), and a coherent curriculum (which provides structured approach and guidance). In this way, the curriculum organization mirrors the subject of its enquiry—Europe is often depicted as a unique socio-cultural space united in its diversity. The BA ES at Maastricht University allows for an exploration of this diversity and Europe’s versatility through a coherent analytical lens anchored in problem-based learning.

Elissaveta Radulova is Assistant Professor at the Political Science Department of Maastricht University and the program director for the Bachelor in European Studies (BA ES). She holds degrees in international relations and European public affairs, and defended a PhD thesis on the non-tangible (discursive) effects of international organizations on domestic policy-making processes. She examines the conditions in which good governance emerges and can be sustained. Among her current research interests are: interest aggregation and representation within the regulatory system of the European Union (EU), and the usage of expertise by EU policy-makers.

[1] According to the THE Young Universities Ranking, accessed on 16 September 2020.

Photo: Maastricht, Netherlands, February 2018. Sculpture with 35 aluminium stars by Maura Biava to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Maastricht Treaty, the basis of the European Union | Shutterstock

Published on November 10, 2020.