This is part of our special feature, Networks of Solidarity During Crises.

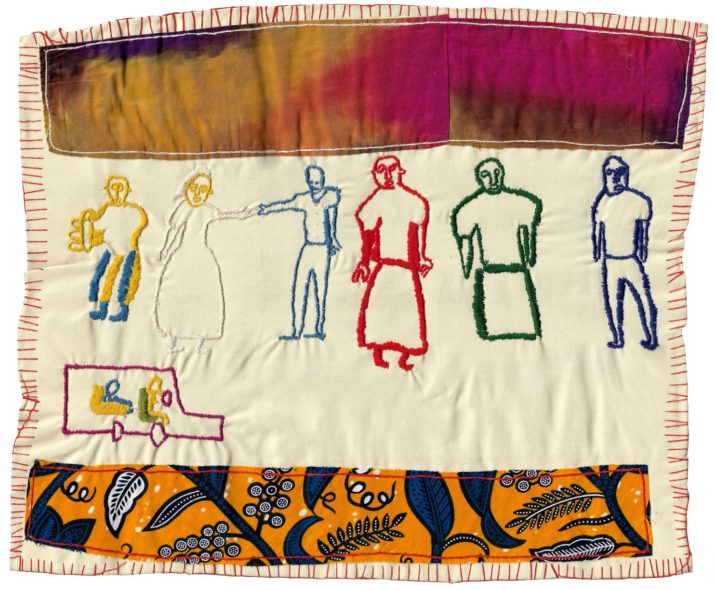

Lucia,[1] a young woman in Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, is abducted, held captive, raped, and brutalized for months. She becomes pregnant and gives birth. To protect reputation for the family, her parents and the parents of the perpetrator pressure Lucia to marry the rapist. Defiantly, she escapes and makes her way to a center that provides refuge and assistance. In a recovery program designed for survivors like Lucia, she creates a story cloth to describe the experience for which she cannot find words.

[photo 1: story cloth, with caption “Forced to Marry My Rapist”]

Lucia says, “I made myself look invisible because no one really sees me.” The leader of the healing circle asks others when they have also felt invisible, and they discuss their experiences together, finding commonality and support.

Common Threads Project is a program addressing the complex psychological needs of women who have been subjected to sexual violence, war, and displacement. In the following pages, we outline the psychosocial consequences of these circumstances, discuss what we believe is needed to be a part of an effective response, and describe the intervention we have implemented for women like Lucia. To access the experiences and healing that can live in a domain beyond words, we have adapted the ancient practice of sewing story cloths as a central aspect of our recovery work.

This phenomenon has been observed across many diverse contexts: women who have experienced severe distress and adversity have often come together to support one another, and to narrate what they cannot speak in the form of stitching story cloths, as seen in this video. Courageous examples of those who have been silenced finding their voices in cloth can be seen in Chilean arpilleras made as testimonials to atrocities committed by the Pinochet dictatorship, in quilts by African American women who were enslaved and in subsequent quilts by their descendants, and in story cloths from South Africa and from the Hmong people of Laos and Cambodia.

Psychosocial consequences of mass trauma

Violence against women and girls is a ubiquitous and pervasive problem, affecting about one in three women worldwide. The psychological, social, medical, and economic consequences are deep and enduring. We have also seen this “shadow pandemic” intensify in parallel with COVID-19. Organizations in many countries are reporting steep increases in all forms of sexual and gender-based violence as women become trapped in their homes with violent intimate partners. Job loss, economic devastation, and high levels of community stress combine to elevate the rates of violence against women.[2]

In regions of armed conflict, sexual violence is a pervasive weapon of war and an effective tool of genocide: devastating individuals and families, terrorizing communities, and contributing to displacement of entire populations. Over the last few decades alone, we have seen this at work in systematic rape committed against millions of women including Rohingya, Yazidi, Bosnian, Syrian, Nigerian, Congolese, Rwandan, and Colombian victims. The perpetrators of these mass atrocities are often treated with impunity while survivors are silenced and their stories excluded from the public discourse.

Not all people subjected to the traumas of sexual violence, armed conflict, and displacement will require specialized services for psychological recovery. The human capacity for resilience is most impressive, and with appropriate community support, many individuals may rebound from these very difficult experiences without professional intervention.[3] However, the conditions of ongoing conflict and destruction of social networks and cultural institutions often thwart the capacity for resilience and recovery, meaning that many survivors do need compassionate, skilled care to relieve suffering and promote healing.

The effects of war experiences cannot be reduced to individual “psychopathology,” but must be understood contextually. By working closely with local practitioners and organizations, we gain an appreciation of how well-being and distress are understood in their community, how women respond to the trauma they have experienced, what community supports are already available, and how these crimes are treated by the state. Whether or not it is permissible or safe to speak out about the crimes in their particular context will influence levels of shame and silence for survivors.

Shame, silence, and troubling ripple effects of unaddressed mass trauma may also continue into the future. There are a range of perspectives in the psychological literature on the long-term effects of severe, collective trauma on subsequent generations. Trauma is believed to be transmitted through biological pathways, patterns of attachment, and socio-cultural narratives about the lived experience.[4]

To give just one example, the profound dissociation, which may serve as a survival response in the face of existential threat, is likely to have a significant impact on the children of survivors. When the sufferer becomes disconnected from her own body, the capacity for attachment may be affected. In some settings, the stigma of rape leads to rejection of victims by families and communities. When young girls who have been brutally raped become pregnant and give birth, they may lose all social support. In our work in the DRC, we have seen the strain this loss places on mother-infant attachment. The transmission of trauma to children often happens unconsciously in the earliest processes of affect regulation.[5] The child has an evolutionary biological need to seek and find security and safety—but this is a daunting task when the parents themselves are unable to find a sense of safety in their own bodies or in their surrounding environment.

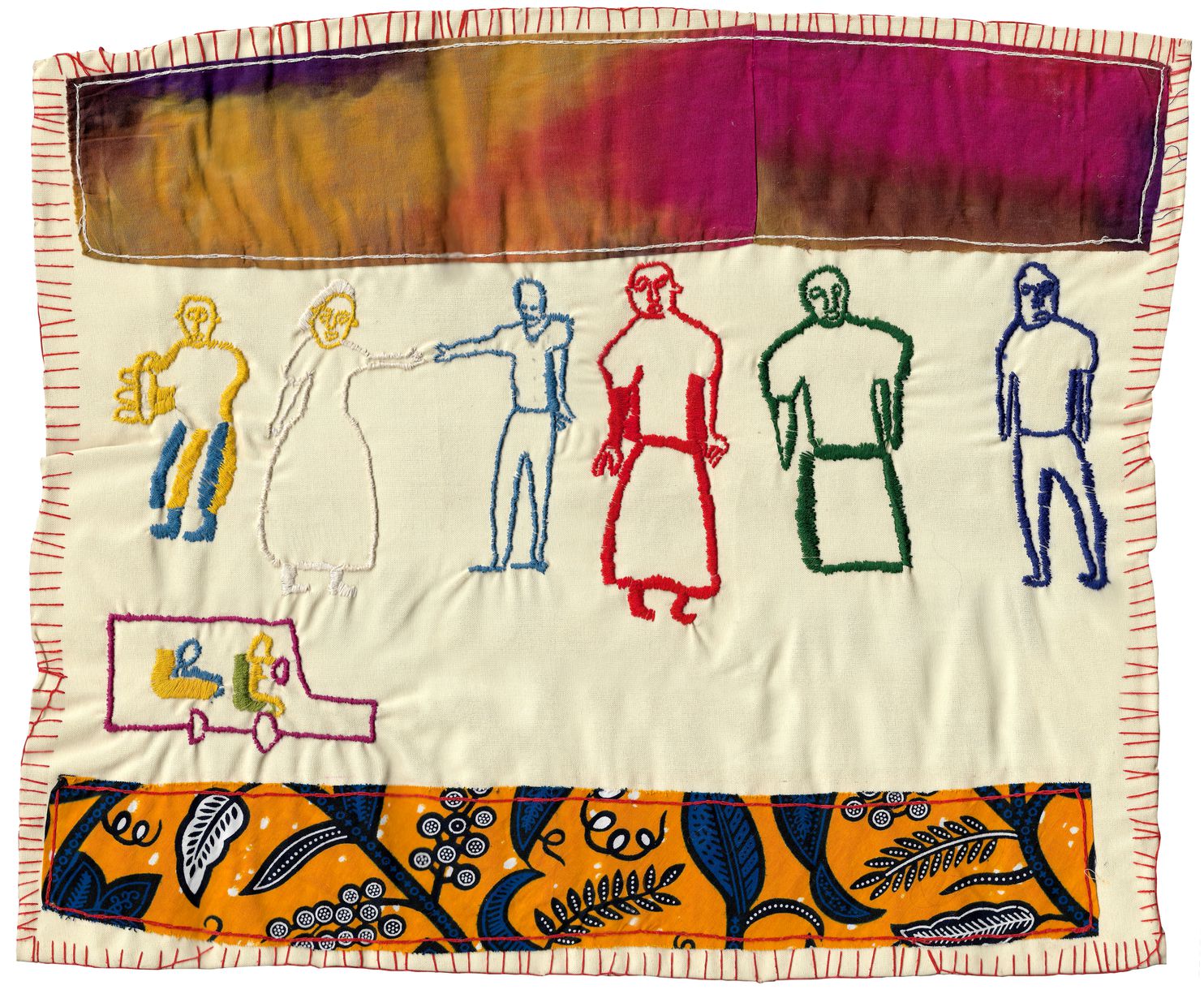

[photo 2: story cloth]

A vision for response

To address the magnitude and depth of mass trauma that is evident in many parts of the world, effective, culturally resonant, sustainable responses to suffering are urgently needed. As well as providing this type of group support, the CTP program respects the local, community-based approaches and the need to address the whole person—somatic, emotional, cognitive, and spiritual. By emphasizing the value of witnessing in the intervention, it allows these silenced crimes to be addressed in more public spaces through the textile art. In our programs, we collaborate with local practitioners who in turn work with a specific subset of the population: women who have been subjected to sexual and gender-based violence in areas of armed conflict and among displaced populations.

It is crucial to avoid pathologizing entire populations who have suffered from mass brutality, and to acknowledge the impact of the socio-political and economic conditions in which people are trying to manage.

There are many fair and reasonable critiques about the imposition of well-intended Western-based trauma interventions that do not take full account of the cultural contexts in which they are implemented, or do not fully engage with the knowledge base of local practitioners. Watters (2010) contends that “within the diversity of different cultural understandings of mental health and illness may exist knowledge that we cannot afford to lose.”[6] We need to value effective indigenous methods of healing already present in the communities and consider how they can be combined (or not) with Western methods.

Bracken (2002), argues for a context–centered approach. He emphasizes that most non-Western cultures do not work with an individualist agenda: “and so major practical difficulties arise when this model is exported.”[7] Bracken quotes Kirmayer (1996) who contends that the need to consider “the social and cultural embedding of distress that ensures that trauma, loss and restitution are inextricably intertwined” and that “psychophysiological processes are embedded in more complex levels of social meaning.”[8] While we believe that some Western methods, if considered carefully and integrated into the local context, can be helpful, we hold these critiques as a compass for our work.

In the humanitarian context, recovery services for survivors of severe atrocities are scarce, and often not as responsive to the above critiques as might be desired. Some women may find their way to medical, legal, economic, or psychosocial assistance. Psychological care provided by international and local aid agencies, in the rare instances where it exists, is often brief, individualized, crisis-oriented, and offers mostly verbal counseling.

Current neuroscience helps us appreciate that some types of severe trauma are stored in the body, in sensorimotor phenomena and in visual images, not in words.[9] When we refer to “unspeakable” atrocities, that is exactly the case. Increasingly, we understand that survivors may not have the words for what they have endured, and therefore they need to access non-verbal channels to achieve healing.

Survivors deserve opportunities for transformative recovery, and we have observed that this is possible. By engaging the participants’ creativity and strengths, by allowing the recovery process to unfold at a gradual pace, by making use of both non-verbal and verbal channels for expression, by working to restore the body’s system of equilibrium, and by enlisting the healing power of peer support, we contend that improved mental health and wellbeing is attainable.

We believe that mass trauma calls for collective, rather than individual modalities of treatment. In her classic work Trauma and Recovery, Judith Herman asserts:

The solidarity of a group provides the strongest protection against terror and despair, and the strongest antidote to traumatic experience. Trauma isolates; the group re-creates a sense of belonging. Trauma shames and stigmatizes; the group bears witness and affirms. Trauma degrades the victim; the group exalts her. Trauma dehumanizes the victim; the group restores her humanity.[10]

Within this group framework, we advocate for an approach that involves healing and integration at multiple levels of experience: the somatic, the emotional, the cognitive, the relational, and the spiritual.[11] When severe trauma appears to fragment all domains of human experience, healing should address all systems so that survivors can experience themselves as whole again.

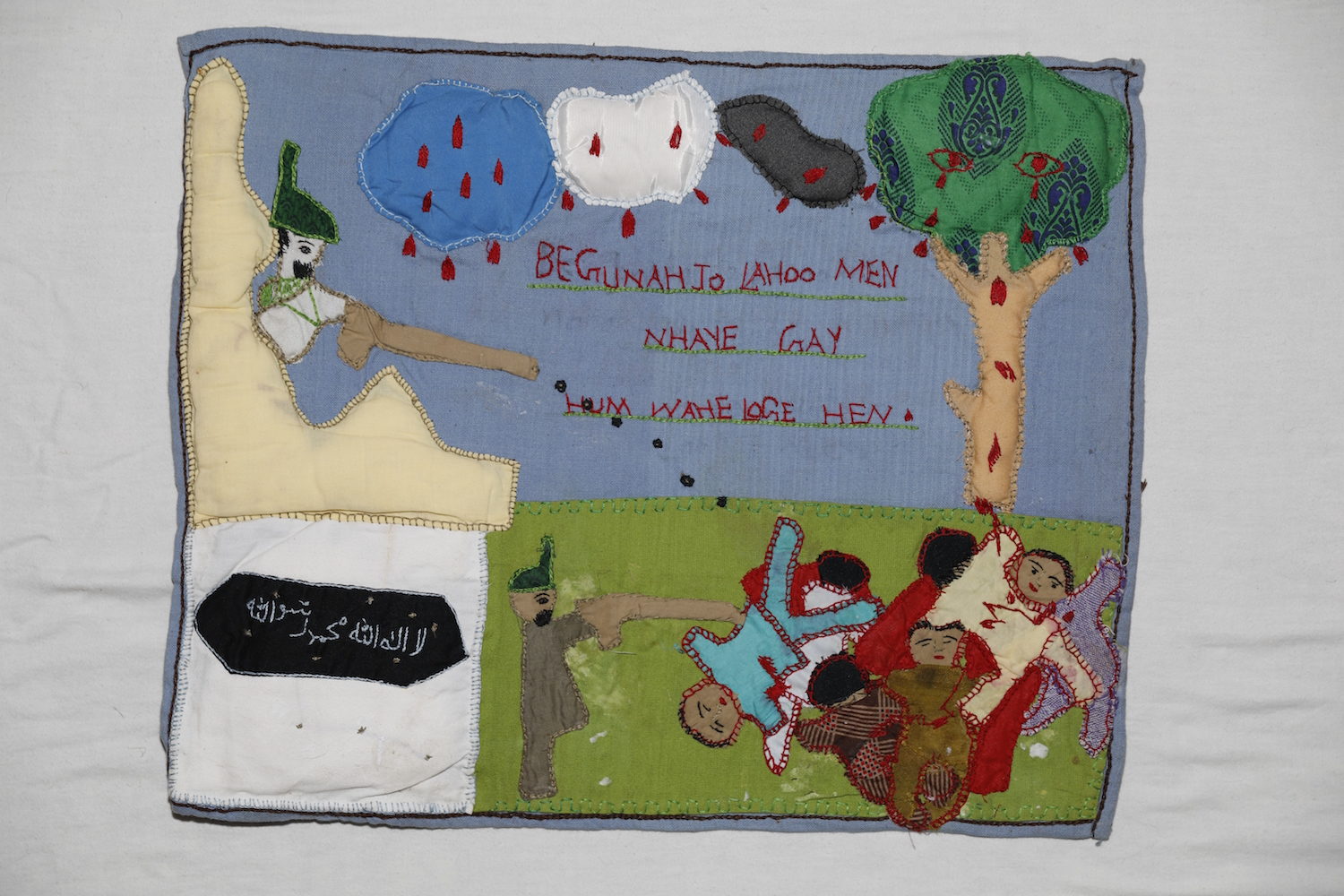

[Photo 3: Story cloth from Nepal]

Following mass trauma, there may be widespread denial of the realities of the sufferers. This makes the need for others to bear witness especially important. Witnessing is important as an act of justice not only for the primary sufferer but also as a way to process the impact for subsequent generations. Dori Laub, whose work focused on the need for trauma survivors to have access to a testimonial community following the Holocaust, contended that:

The role of the witness… is essential to the testimony process in that it provides the survivor with an empathic listener who offers the human connection that makes confronting the reality of trauma bearable.[12]

What is Common Threads Project?

In close collaboration with local partners in Ecuador, Nepal, Bosnia, and DRC, Common Threads Project has developed a program to address lasting psychological wounds for the most severely affected. The ultimate goal, where possible, is not only to restore functioning and reduce symptoms, but to emerge from isolation and shame, to nurture community with others who have suffered in similar ways, to reclaim voice and agency, to rebuild a sense of meaning and purpose, and to make the journey from victims to survivors to agents of change. In this section we describe the methods we have developed to achieve this kind of integrated recovery.

At each site, the circles are facilitated by local mental health practitioners who are well trained, supervised, and mentored by Common Threads Project. Circles of about ten to fifteen women meet with two trained facilitators for six months of intensive weekly sessions.

The making of story cloths is one aspect of a comprehensive, integrative program of recovery in Common Threads circles. The intervention begins with building emotional and physical safety within the group. The circle establishes an atmosphere of support and teamwork before beginning the story cloths. Drawing on techniques from Somatic Experiencing,[13] Sensorimotor Therapy,[14]and Polyvagal work,[15] participants learn exercises that calm and slow down activation, regulate breathing, orient to the here-and-now, and help to reconnect with the body.

Another aspect of the initial phase of the program is providing essential information to the women about the bio-social-psychological impacts of trauma. They find relief in knowing that the symptoms they experience are normal adaptive responses to abnormal circumstances.

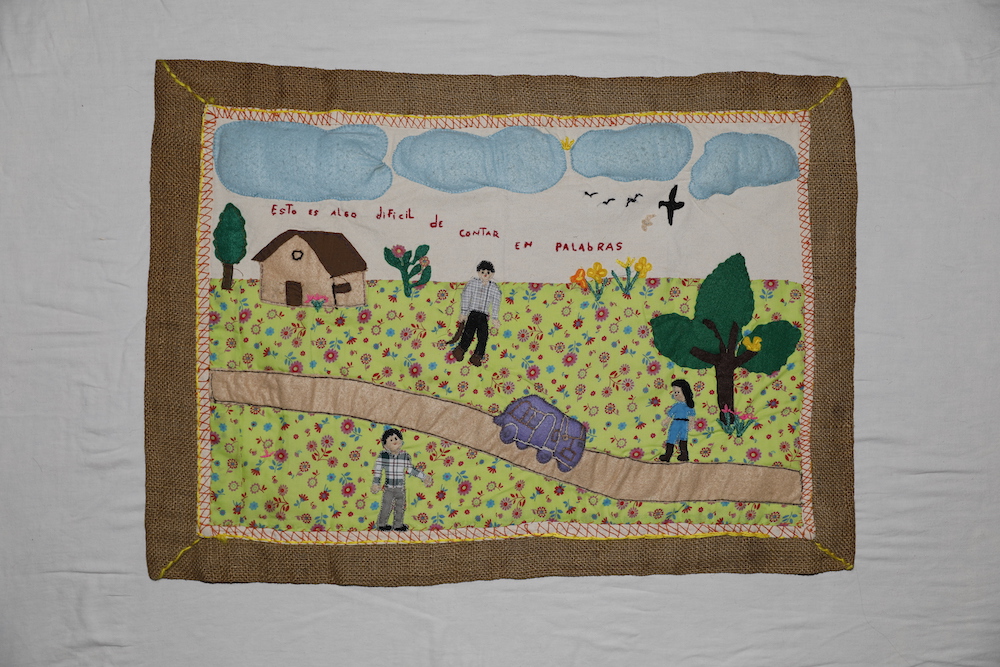

Trauma heals through bonding and attachment and by paying attention to emotional and physiological safety in the room. Once the group has established strong skills for safety and stability, they are ready to embark on story cloths that invite them to share in images, topics that may be difficult to express otherwise. This organic expressive tradition is very well-suited as a foundation for recovery. The story cloths enable a safe process of disclosure at a gradual, gentle pace. There is no pressure to verbalize, and no rush to reenter the traumatic experience. Emotional safety and personal disclosure are enhanced when the hands are busy and there is no demand for eye contact. The slow, rhythmic, meditative action of hand stitching is intrinsically calming and allows the women to tolerate an emotionally intense process in a grounded body-state. Placing one’s inner pain “out there” onto the cloth, brings a sense of relief. A woman in the Ecuador program said “I feel like I’ve rid myself of a heavy load, a load I carried. It’s passed now. I am getting rid of things that I had carried in my heart.”[16] Making an intricate and concrete object out of an experience of suffering seems to offer the creators a sense of mastery, where previously there was a sense of helplessness.

[Photo 4: story cloth from Ecuador]

The participants in Common Threads circles use the story cloths to move from social isolation and stigma into connection; to share their stories, to be understood:

The pain we were going through was inside our hearts for a very long time, but we were unable to pour it out in any form. This was a shared pain…. I have tried to reflect the situation because the situation is indescribable. But with this, I felt quite relieved.[17]

A sense of pride about their strength and capacities begins to replace a sense of shame about what they have endured.

As summarized by Brad Evans and Bracha Ettinger (2016): “We join in sorrow so that silenced violence will find its echo in our spirit, not by imagination but by artistic vision.” They compare art to the work of “maternal healing, when it solicits against all the odds the human capacity to wonder, to feel awe, to feel compassion, to care, to trust and to carry the weight of the world.”[18]

Trauma memories are like small shards of the past that get trapped in the present, often in debilitating ways. By learning to feel a sense of bodily safety and integrity while holding these memories, and to creatively symbolize these memories in the images of the story cloths, a healing process is possible.

Gradually, the women explore the themes and questions raised by the story cloths. They find in them not only memories of trauma, but also evidence of personal strength, oases of safety and support, and lessons of coping. The therapeutic aim is not to simply disclose one’s story, but ultimately to experience those memories in a new way: free of shame, self-blame, survivor guilt, and self-hate.

The Common Threads approach emphasizes the strengths and capacities of the participants, and works to build the self-esteem that has typically been eroded by circumstances of oppression. The women take pride in their work, and find new ways to express themselves. “I think that now I am stronger, I believe in myself more.”[19] Circle participants gain self-confidence in sharing their work with one another. Later the women create collective story cloths that focus on commonality, and on their sense of a shared present, and possibilities for the future.

Once they have completed the initial six-month program, survivors sometimes decide to display their story cloths publicly as a way of amplifying their voices beyond their own healing circle. These exhibits give others a chance to bear witness to both the suffering and the courage of the survivors who made them.

“Only Some Cross to Safety” is a collective story cloth made by a circle in Bosnia to recall a moment during the war when Bosnian Serb troops surrounded their village, forcing them to flee over the mountains. When they reached the bridge, men and teenaged boys were held back by the soldiers while women and children were allowed to cross. Many of their family members were never seen again. One of the group comments

“When I take a look at our work I see so many details, I see all of us … On this cloth are parts of our lives.”[20]

One of the circles of women in Bosnia choose to exhibit their group story cloth in a public place in a community hall at the entrance to the Una National Park. As a woman in the circle said:

After everything it is a proof how we are connected, how much we are close to each other. It is so special and beautiful, we are together on that cloth like here in reality. I am proud of our work![21]

It was crucial to the women that the work be viewed by others. Common Threads Project is not only a psychotherapy intervention, but it also works to create testimonial communities. Because the circle becomes like a new “family,” the women often opt to continue to meet together going forward, without the facilitators.

The need to tell our stories to others has been a part of human experience since people began to draw their “stories” on the walls of caves. Story-telling allows us to describe our personal experiences and make meaning of them with others.

The story cloths that the women create in Common Threads Project are the core of a nuanced therapeutic process, precariously balanced between the desire to remember and the desire to forget. On the one hand, we need to tell our stories to be understood, but at the same time, we are designed to protect ourselves from the profound pain of remembering. The story cloths may be one way to manage that paradox.

Integrative psychotherapy that is culturally appropriate and effective for trauma is needed for many women who have been subjected to sexual violence, but it is not sufficient. This kind of psychological support for trauma treatment must also be accompanied by legal actions that counteract impunity, socioeconomic measures that strengthen the life circumstances of women, community work toward reintegration of victims, and considerable efforts to alter the gender norms and social structures that perpetuate violence against women.

Rachel A Cohen, PhD. is a clinical psychologist and Founder and Executive Director of Common Threads Project. Before launching this organization, she was in clinical practice for nearly 30 years. Specializing in trauma recovery, she has designed projects and trained local staff in post-conflict areas, including Bosnia, South Sudan, Uganda, Kenya, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ecuador, and Nepal. She earned her doctorate from the University of Michigan in 1986, and a certificate in global mental health from the Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma in 2010.

Catherine Butterly, Msc, is a Psychotherapist, Family Therapist, University lecturer and Programme coordinator of the M.A in Counseling at Webster University, Geneva, Switzerland. She has worked in the field of trauma for over 20 years in a variety of settings and locations. She is a senior advisor and trainer with Common Threads Project in Bosnia and Eastern Congo and collaborates with a number of organisations working with people in insecure environments resulting from war and displacement.

References:

Bracha Evans and Brad Ettinger, “Art in a Time of Atrocity,” New York Times, December 16, 2016.

Bessel Van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma (New York: Viking, 2014).

Caren Grown and Frank Bousquet, “Gender inequality exacerbates the COVID-19 crisis in fragile and conflict-affected settings,” World Bank Blogs, July 9, 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/dev4peace/gender-inequality-exacerbates-covid-19-crisis-fragile-and-conflict-affected-settings Common Threads Project, unpublished internal report, 2018.

Deb Dana and S. Porges, The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018).

Dori Laub, “Testimonies in the treatment of Genocidal Trauma,” Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 4:1 (2002).

Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The globalization of the American psyche (Free Press, 2010).

Haley Peckham, Epigenetics: The Dogma-defying Discovery that Genes learn from Experience.

The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy, July 2013.

Jill Salzberg, The Texture of Traumatic Attachment: Presence and Ghostly Absence in Transgenerational Transmission’ The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 2015, Volume LXXXIV, N.

Joop T. V. M. De Jong, “Closing the gap between psychiatric epidemiology and mental health in postconflict situations,” The Lancet 359 (2002).

Judith L. Herman, Trauma and Recovery (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

Laurence J. Kirmayer, Landscapes of Memory: Trauma, narrative and dissociation. In P. Antze & M. Lambek (eds.), Tense Past: Cultural Essays on Memory and Trauma (London: Routledge, 1996).

Pat Bracken, Trauma, Culture, Meaning and Philosophy (London: Whurr Publications, 2002).

Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Claire Pain, Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy, (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006).

Peter A. Levine, Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2015).

[1] Pseudonym to protect privacy

[2] Caren Grown and Frank Bousquet, “Gender inequality exacerbates the COVID-19 crisis in fragile and conflict-affected settings,” World Bank Blogs, July 9, 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org/dev4peace/gender-inequality-exacerbates-covid-19-crisis-fragile-and-conflict-affected-settings

[3] Joop T. V. M. De Jong, “Closing the gap between psychiatric epidemiology and mental health in postconflict situations,” The Lancet 359 (2002), 1793-1794.

4 Haley Peckham, Epigenetics: The Dogma-defying Discovery that Genes learn from Experience.

The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy, July 2013.

[4] 4 Haley Peckham, Epigenetics: The Dogma-defying Discovery that Genes learn from Experience.

The Neuroscience of Psychotherapy, July 2013.

[5] Jill Salzberg, The Texture of Traumatic Attachment: Presence and Ghostly Absence in Transgenerational Transmission’ The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 2015, Volume LXXXIV, N.

[6] Ethan Watters, Crazy Like Us: The globalization of the American psyche (Free Press, 2010), 7.

[7] Pat Bracken, Trauma, Culture, Meaning and Philosophy (London: Whurr Publications, 2002) 73.

[8] Laurence J. Kirmayer, Landscapes of Memory: Trauma, narrative and dissociation. In P. Antze & M. Lambek (eds.), Tense Past: Cultural Essays on Memory and Trauma (London: Routledge, 1996), 173-198.

[9] Bessel Van der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body in the Healing of Trauma (New York: Viking, 2014).

[10] Judith L. Herman, Trauma and Recovery (New York: Basic Books, 1992).

[11] By spiritual we mean not just organized religion, but meaning-making, sense of purpose, and however spirituality might be defined in the local context.

[12] Dori Laub, “Testimonies in the treatment of Genocidal Trauma,” Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 4:1 (2002), 65.

[13] Peter A. Levine, Trauma and Memory: Brain and Body in a Search for the Living Past (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2015).

[14] Pat Ogden, Kekuni Minton, and Claire Pain, Trauma and the Body: A Sensorimotor Approach to Psychotherapy, (New York: W. W. Norton, 2006).

[15] Deb Dana and S. Porges, The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation (New York: W.W. Norton, 2018).

[16] Interview with participant in Bosnia, unpublished internal report, Common Threads Project, 2018.

[17] Interview with participant in Nepal, unpublished internal report, Common Threads Project, 2015.

[18] Bracha Evans and Brad Ettinger, “Art in a Time of Atrocity,” New York Times, December 16, 2016.

[19] Interview with participant in Bosnia, unpublished internal report, Common Threads Project 2018.

[20] Interview with participant in Bosnia, unpublished internal report, Common Threads Project, 2018.

[21] Interview with participant in Bosnia, unpublished internal report, Common Threads Project. 2018.

Published on October 13, 2020.