Struggles for Climate Justice: Uneven Geographies and the Politics of Connection

Struggles for Climate Justice: Uneven Geographies and the Politics of Connection

By Brandon B. Derman

Publisher: Palgrave Macmillan

Recommended by Hélène B. Ducros

Climate (in)justice is one of those terms that has surfaced as environmental concerns have become prominent in public debates and scholars, activists, community leaders, and policy-makers have joined in a reflection on the differentiated effects of anthropogenic climate change on populations across the globe. But what does it mean? What does climate injustice look like and who is responsible for it? Once identified, what obligation for action does it trigger and what are the challenges to contesting climate injustices? What are the resources needed to successfully address it? What are solutions, who is seeking them, with what means, and at what scales? On what grounds do people disagree about what to do and how? What are the local, national, and international legislative frameworks under which change is made possible (or impossible)? With what other “justices” does climate justice conflate? Those are among the many questions that Brandon Derman’s latest book helps ask and answer through the notion of relationality. Struggles for Climate Justice: Uneven Geographies and the Politics of Connection is articulated around the key premise that climate justice is about the “politics of connection,” which rests on three intersecting sets of relations. These include an array of socio-ecological, socio-spatial, and governmental configurations operating at different scales and under the impetus of various actors’ responses to injustice.

Focusing on these relationalities as co-producers of climate injustice, the book unearths what other injustices and inequalities have historically partaken in the unevenness of stark climate change consequences for the most vulnerable populations, raising the thorny and compelling question of “climate rights.” As he considers well-chosen case studies and different COPs (conference of the parties under the UNFCCC) he attended, Derman disentangles a global climate governance landscape where geo-economic power politics plays out to devise climatic futures that are contested. From disappointments in Copenhagen in 2009 over limited mitigation decisions, to the hopes generated by the Paris Agreements―championed for having redefined the relationships between those countries deemed to hold responsibility for anthropogenic climate change and those incurring the most damaging effects―the volume critically explores global climate mandates, also delving into alternative frameworks, such as transnational activism. This book is set to become a foundational tool for climate justice policy advocates and local leaders in marginalized communities, as well as students and scholars of environmental studies, geography, social movements, and public international law.

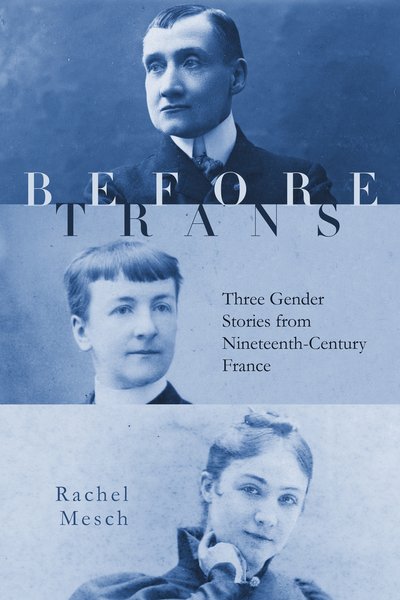

Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France

By Rachel Mesch

Publisher: Stanford University Press

Recommended by Louie Dean Valencia-García

Trans lives matter—and so do the lives of gender non-conforming people from before we had our modern understanding of trans identity. Rachel Mesch’s Before Trans: Three Gender Stories from Nineteenth-Century France focuses on the lives of three gender non-conforming people in France’s post-revolutionary period: Jane Dieulafoy, Rachilde, and Marc de Montifaud. More than anything, this book argues historians need to look back at the past, knowing what has been learned about gender variability more contemporarily, to see ways in which that variability played out in the past—on its own terms. Rather than spending her time talking about the need for trans history, the author provides a path forward for historians by doing that hard work. Using queer theory in practice, the immensely readable book provides excellently researched biographies strung together to show complex worlds where gender norms mattered, but could be transgressed. While focusing her study on artistic and literary circles, Mesch’s figures are fighters and adventurers, anti-feminists, and fin-de-siècle writers. Mesch admits to having once understood “Joan Scott’s famous delineation of gender as a ‘useful category of historical analysis’” in “chiefly binary terms.” For this reason, Mesch has expanded her own work here to consider variability—creating nuanced, intimate portraits of her subjects. The nineteenth century historian argues, “my own fields of French literature and history have largely overlooked [gender variability], even in their explorations of the history of sexuality.” Mesch’s book adds an important contribution to recent work in trans history, including that of Thomas Abercrombie and C. Riley Snorton. Like those authors, Mesch avoids placing contemporary terms onto the past—respecting the agency and identities of the historical figures studied.