Translated from the Swiss by Olivia Baes.

Yet, at the end of April, he broke his leg.

On account of early snow the previous Fall, they hadn’t been able to finish chopping wood in Sassette, and they’d gone back there, Théodule Chabbey, old Romain Aymon, Jean-Pierre Carraux, and Fardet – Jean-Luc was the fifth. It is, in the gorge of La Zaut behind Le Bourni, a steep and rocky slope that runs straight down to the flowing torrent, full in this season.

At a very early hour, they had already started their drudgery; the fir trees in question had bent over the void on their own as a result of the weight of the branches up top, there was no need to tie the rope, the men attacked them at the root; when the notch was deep enough, they broke, smashing on the rockery, bouncing all the way to the path.

There was still fog. It had taken shape little by little, rising from the bottom of the gorge like water does in a basin. Strangled between boulders, the great rumble of water filled the air; the men could hardly hear one another. There they were, hanging on the slope: then, a little further ahead, it steepens some more, and suddenly, it becomes a real wall, a hundred-meter wall. Where the bisse runs, a great wooden canal suspended in the air, fixed with beams dug into cracks in the rock, thus reaching the length of the wall up to the areas of lingering snow, from which it gathers the water that serves to irrigate meadows; without which, the climate is too dry, the grass would burn quickly. You see it shrink, still overhanging the void, now like a string, marked in black against the lighter stone, then suddenly turn, disappear.

They worked all morning; around noon they ate; following which, they immediately took up their axes again, for work was calling. Nonetheless, around three, they found themselves rather ahead, as only one out of the five trees they had to chop down still stood standing, the largest one, yes, but old and rotten; and Théodule had started on it, while under him, Jean-Luc and Romain had begun to limb the tree. Neither of them spoke, too busy, and out of breath too; due to habit and the way it forms, the men no longer even heard the great sound of the water, it was turned into silence; nothing but the axes chopping away, the larger strokes, Théodule’s on the fly, and the other shorter and sharper hacks of Jean-Luc and Romain.

The sun had lowered in the sky; suddenly it pierced through the clouds, the large side of the bisse turned pink; somewhere water dripped, there was a damp layer, it shone like gold.

Smoke was rising from the hills, and, faraway, at the bottom of the great valley, the vast land came into view, with the river’s silver bar and at the back of the horizon, a heap of tall mountains. A great bird of prey appeared and hung in the air for a moment; then it fell like a stone.

A small warm wind had blown in, vapors passed, rising then coming undone, much like

fine wisps of ink in the fallen light, where the sun had drowned. You could already smell the damp scent of the evening.

You could still hear the axe hacking away at the heart of the tree, Théodule lifting the tool with the long handle, swinging it forward with a rounded movement of the shoulders; the shiny iron bouncing out of the widening notch. Suddenly the trunk cracked. Théodule cried: “Watch out!” then began to strike again; the tip of the fir tree shook. “Watch out!” Théodule cried once more. But his mouth was still wide open when the trunk showed something like hesitation; it leaned to the right, it leaned to the left, and Théodule barely had enough time to leap back: the entire mass fell, amongst the whistling of branches, collapsed and rolled in a sort of pine needle smoke as bark debris launched into the air around him; then, all of a sudden, Romain, who had hidden behind a large rock, came running, screaming: “Ah! My God! he’s trapped underneath.” And those who were still on the path climbed the slope in great haste.

Jean-Luc was indeed lying there, having been trapped during his escape. His bottom half was trapped, so that only his top half showed, with a face like the white of bread, and wide open misty eyes. The forehead’s skin was split open, blood had trickled down to his moustache; his chest was bare. And did not stir, flat on his back, arms far apart, like those of a man nailed in the shape of a cross.

So that at first they thought he was dead, and Romain, who was pious, crossing himself, said a prayer, as they observed from his moving lips, while the others remained standing there, filled only with great astonishment. Then Fardet removed his hat and said twice: “Hell! Hell!” Théodule, behind his large black beard, had grown even paler than Jean-Luc; he said: “I did cry out, only the trunk was rotten at its core.”

But suddenly Jean-Luc let out a sigh, the red color of blood creeping back under his skin, he looked around him, most likely remembered everything; he said: “It’s nothing, only my legs are trapped.”

They pulled him out from where he was, they laid him out on a flat mossy surface, they placed a garment rolled up in the form of a pillow under his head, and, because Romain had gone to get the small keg, the wine finished warming him and helped him to regain his senses. Then they examined how hurt he was; along with his shirt, his pants had been ripped to bits, and, though one of his legs was only scratched and bruised, when they touched the other, he groaned. Below the calf, the bone had broken, so that it was already very swollen, and, on one side, a black blood clot hung from the wound.

“It’s nothing!” repeated Jean-Luc, for he was courageous. Upon which Romain said to him: “Take another swig.” Jean-Luc drank. The four of them lifted him up, they carried him to the path.

Having made a kind of stretcher with branches and rope, they laid him down on it, then were off. Romain had taken the lead. The others slowly followed the path that borders the gorge, which goes on widening, then opens up, and you arrive in the meadows; then the village appears.

She had come to meet him, and, as soon as she saw a speck in the distance, ran, just as Romain had found her, her sleeves rolled up, her apron soaked (for she’d been doing the dishes and had left in a hurry) – she started to run from afar, and arrived, throwing herself at him: “What’s wrong? she said, what’s wrong?” For she feared that Romain hadn’t told her the truth. Jean-Luc answered her: “I’ve broken my leg.” Then she kissed him in front of everyone, many people having already come; she repeated: “Is that really the truth? the truth? and this blood!” And she wiped this blood, with her handkerchief, then went off towards the house; and when the men arrived with the stretcher, the bed was already made, the water on the fire, the cloth for the bandages all prepared. Then, as soon as Jean-Luc was in bed, she sat near him.

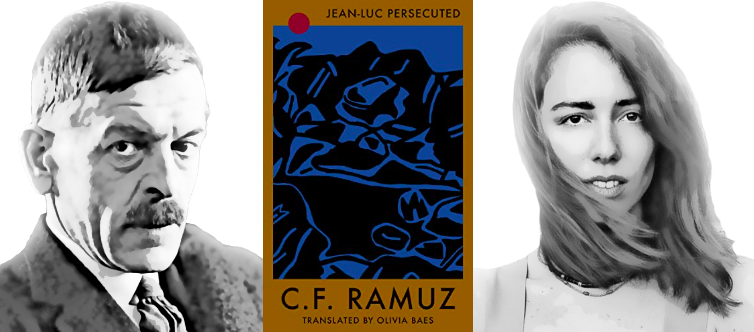

Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (born Sept. 24, 1878, Cully, Switz.—died May 23, 1947, Pully, near Lausanne) was a Swiss novelist whose realistic, poetic, and somewhat allegorical stories of man against nature made him one of the most iconic French-Swiss writers of the 20th century. As a young man, he moved to Paris to pursue a life of writing, where he struck up a friendship with Igor Stravinsky, later writing the libretto for The Soldier’s Tale (1918). Ramuz pioneered a common Swiss literary identity, writing books about mountaineers, farmers, or villagers engaging in often tragic struggles against catastrophe. His legacy is remembered through the Ramuz Foundation, which grants the literary award Grand Prix C.F. Ramuz.

Olivia Baes is a Franco-American multidisciplinary artist who grew up between France, Catalonia, and the United States. She holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Comparative Literature and a Master of the Arts in Cultural Translation from the American University of Paris. She has written multiple feature-length screenplays, including L’Homme au piano and Riches, which was selected as a project in development for the 70th Cannes Film Festival. Her translations include a co-translation of Me & Other Writing by Marguerite Duras (Dorothy, a Publishing Project) and Jean-Luc Persecuted by Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz (Deep Vellum).

This excerpt is published by permission of Deep Vellum Publishing. Translation copyright © Olivia Baes 2020.

Published on June 3, 2020.