This is part of our special feature, Imagining, Thinking, and Teaching Europe.

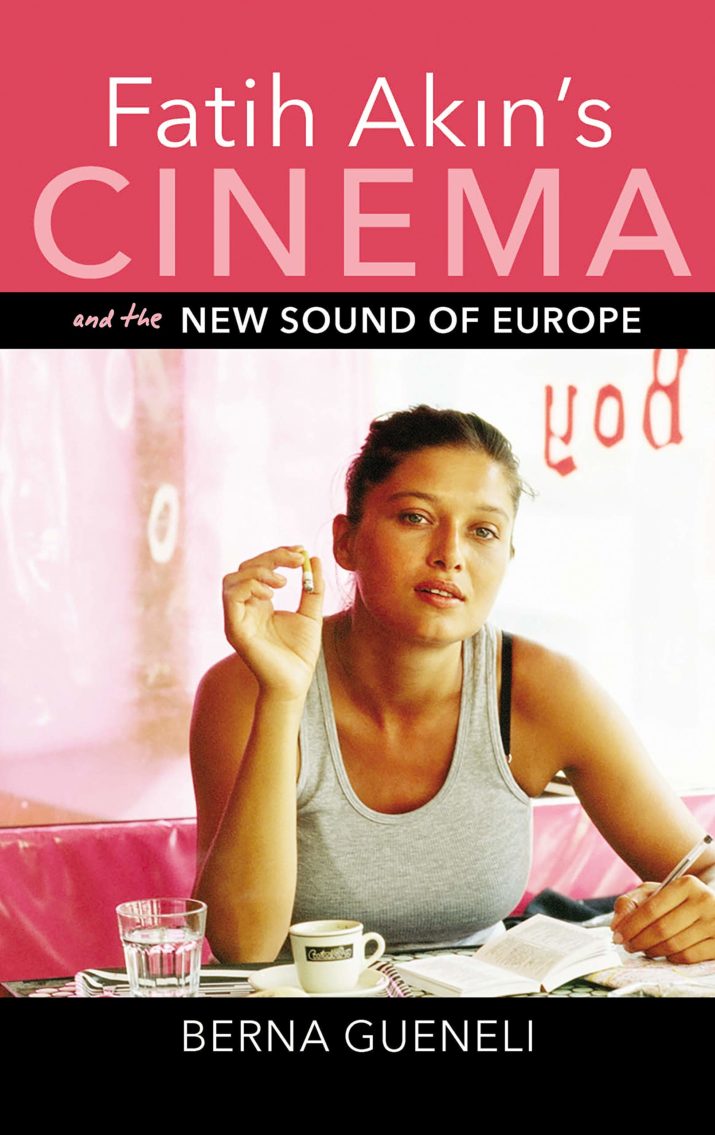

Fatih Akın’s Cinema and the New Sound of Europe is a welcome addition to the scholarship on German-Turkish auteur director Fatih Akın. Focusing on the first period of Akın’s career, which author Berna Güneli terms a period of “Turkish German Entanglement,” (6) the book examines three films in depth. These include two films from Akın’s trilogy “Love, Death, and the Devil” (2004-2014)—namely Head On (2004) and On the Edge of Heaven (2007)—as well as the earlier road movie In July (2000). Güneli’s analyses uncover multifaceted links to Turkish film history, particularly through casting, setting, and soundtrack decisions that reference iconic Yesilçam films from the 1960s-1970s (107-109; 113). The final chapter also delves further into the diverse cinematic references that Akın synthesizes in his work, while also briefly touching on additional films from Akın’s oeuvre, including Short, Sharp, Shock (1998), Soul Kitchen (2009), The Cut(2014) and In the Fade (2017). Highlighting the uncategorizability of Akın’s cinematic practice, Güneli draws connections between his work and Hollywood-, European art house-, and European popular films, as well as select films from New Turkish Cinema. Here Güneli also shows how the films of Nuri Bilge Ceylan—an important director of New Turkish Cinema—expand the trajectory of “European” film, by mixing elements of art house cinema and Yesilçam melodrama to focus on rural Turkey. In short, Güneli reads Turkish cinema as integral to a European cinema it has traditionally been deemed separate from, while also underscoring the transnational dimensions of “Turkish” and “European” cinema alike.

At the core of Güneli’s film analyses are the diverse “soundtracks” of Akın’s films. In her specific focus on polyphony, Güneli builds on previous scholarship, which has situated Akın’s work in the tensions between a “Fortress Europe” marked by borders and exclusivity and a “New Europe” marked by mobility and integration (18). The linguistic and musical diversity of Akın’s films, she argues, upends the fantasy of a multilingual Europe made up of homogenous, monolingual nation states (111-112); inherently polyphonic in nature, the aural elements of Akın’s films work together with the visual to present rather a transnational vision of Europe that is not confined to the Schengen or EU realms. Akın’s cinematic practice, she concludes, “undermines [the EU’s] Schengen freedom of movement… by extending the spheres of Europe well into northeastern Turkey, and by … including sounds associated with the peripheries of a geopolitical Europe” (11). The strength of Güneli’s work lies in her attention to a multitude of said sounds—including music, urban and rural sounds, languages, dialects, and accents.

Drawing on Michel Chion’s theory of the “acousmatic”—or a recorded sound employed in film to depict a setting different from that of its enunciation—Güneli notes that viewers must always engage in a process of “mapping” filmic sounds. Yet in a road movie like In July, she argues, “sound maps Europe” (48). In other words, sound works together with the routes and landscapes of the film to present a “diverse and multiethnic vision of Europe” (67). In the opening scene in Bulgaria, for example, the main character Isa (Mehmet Kurtuluş) plays a song by popstar Sezen Aksu in his car, which he is using to transport the body of his deceased uncle from Germany to Turkey. This reverse movement of Turkish pop music, which has historically been imported to Germany from Turkey in the form of tapes, points to a multidirectionality of migration that is reflected in the broader soundtrack of the film. Within In July, for example, Güneli analyzes Aksu’s music alongside that of Brooklyn Funk Essentials—a multiethnic band employing elements of acid-jazz, funk and hip hop—and the Hamburg-based Brazilian-German reggae band Niños con Bombas, to name only three of the films diverse musical influences.

Güneli’s attention to the musical soundtrack of The Edge of Heaven is similarly perceptive. In her analysis of Turkish-German character Nejat’s (Bakı Davrak) first perusal of a German bookstore in Istanbul, for example, Güneli notes Akın’s choice of diegetic music: an arrangement of Bach’s “Minuet in G Minor” for the banjo, performed by the US musician John Bullard. Whereas Bach typically symbolizes high-brow German culture, the instrument of the banjo is more readily associated with Irish or American folk music. Together with a fake Goethe quotation employed earlier in the film, Akın’s implementation of an Americanized Bach song subverts the concept of a (highbrow) German Leitkultur—or leading culture—which is otherwise hinted at through the shelves of books surrounding the two men. In contrast to the recognizable, (if slightly “accented”), Bach, Güneli notes how other key sounds in the film that have otherwise been deemed alien to German culture—such as the call to prayer—serve rather as a point of connection between diverse characters.

Güneli also pays due attention to localized music, such as the traditional melodies (Yusuf Kaba’s “Çamburnu”) and Black Sea dialects (Kazım Koyuncu’s “Ben seni sevduğumi”) featured in the soundtrack of The Edge of Heaven. She then ties this into her focus on the linguistic diversity of the film, which employs multiple accents and dialects of German, Turkish, and English. While Güneli highlights elements of multilingualism in all of Akın’s films, her analysis of The Edge of Heaven is particularly skillful, as she unravels what she terms a democratization of accented languages. Here, Güneli goes beyond Hamid Naficy’s concept of an accented cinema, which describes a specific mode of production marked by the migration, exile, and displacement of postcolonial and so-called Third World filmmakers living in the West. In a film like The Edge of Heaven, “accented” language and linguistic variation is rather the norm, and monolinguality a minoritized exception. Within this linguistic soundscape, dialects are furthermore detached from a limited sense of geographic locality. Güneli notes, for example, how the character Ali Aksu utilizes sounds otherwise associated with the Black Sea dialect of Turkish even when he is speaking German. This form of contact, she argues, “characterizes languages as permeable, flexible, and in constant change” (120). While not every viewer has the linguistic capabilities to discern such subtleties, this is also part of the democratizing aspect of the film, which does not single out migrants and foreigners as different. Rather than act as a force of exclusion, the film’s multilinguality thus also has a democratizing function for viewers, who experience the film through subtitles.

Güneli’s analysis of multilingualism in Head On is similarly insightful. In her analysis of the second-generation Turkish-German character of Sibel (Sibel Kekilli), for example, Güneli does not simply link the ease with which she traverses national borders to her ability to seamlessly code switch between German and Turkish. She delves further into the multiple registers of German and Turkish that Sibel navigates, in order to underscore how language is closely tied to the film’s simultaneous employment and subversion of stereotypes. These same questions pertain to Sibel’s cousin Selma (Meltum Cumbul), who is a successful businesswoman from Istanbul. Selma’s use of a high-register, Istanbul dialect of Turkish is but one marker of her independence and financial success in the film. Although this raises other stereotypes about the relative value of certain dialects over others, Güneli highlights Selma’s significance as “a rare, talkative, urban, and secular view of Turkish femininity in German film” (89), which counters earlier portrayals of feminine domesticity in films such as 40 Square Meters of Germany (1986) and Yasemin (1988).

Overall, Güneli provides fresh and multifaceted readings of Akın’s films. While her analyses highlight Akın’s particular “aesthetic of heterogeneity” from the diverse perspectives of casting, costume, and setting, I have chosen to focus here on her astute observations regarding sound, which will appeal to readers far beyond the field of Turkish-German studies, to those working in European studies, film history, multilingualism, and sound studies. Through careful attention to detail, Güneli successfully highlights the linguistic and musical range of Akın’s soundscapes, to demonstrate the particular manner in which his films aurally diversify Europe, without ever exoticizing certain sounds as Other or as foreign. In conjunction with Akın’s diverse casts and the multiple regions his films traverse—including Germany, Turkey, and the Balkans—the unique mix of sounds presented in Güneli’s book underscore an important normalization of ethnic minorities in Europe (6). This normalization has important ramifications for European cinema at large, within which Güneli skillfully locates Akın’s cinematic practice. At the same time, she brilliantly demonstrates how Akın leads his viewers to reconsider the geographic and linguistic borders of “Europe” beyond the political borders of the EU, and its ideological and constructed social forms of identification such as whiteness and Christianity.

Kristin Dickinson is Assistant Professor of German Studies at the University of Michigan. Her teaching and publications focus on questions of world literature, multilingualism and cross-linguistic remembrance, nationalism and the history of language reform, and non-ethnic modes of belonging in both Turkish and German contexts. Her current book manuscript DisOrientations: German Turkish Cultural Contact in Translation (1811-1946) is under review for the Germans beyond Europe series with Penn State University Press.

Fatih Akın’s Cinema and the New Sound of Europe

By Berna Güneli

Publisher: Indiana University Press

Paperback / 208 Pages / 2019

ISBN-13: 978-0253024459

Published on June 3, 2020.