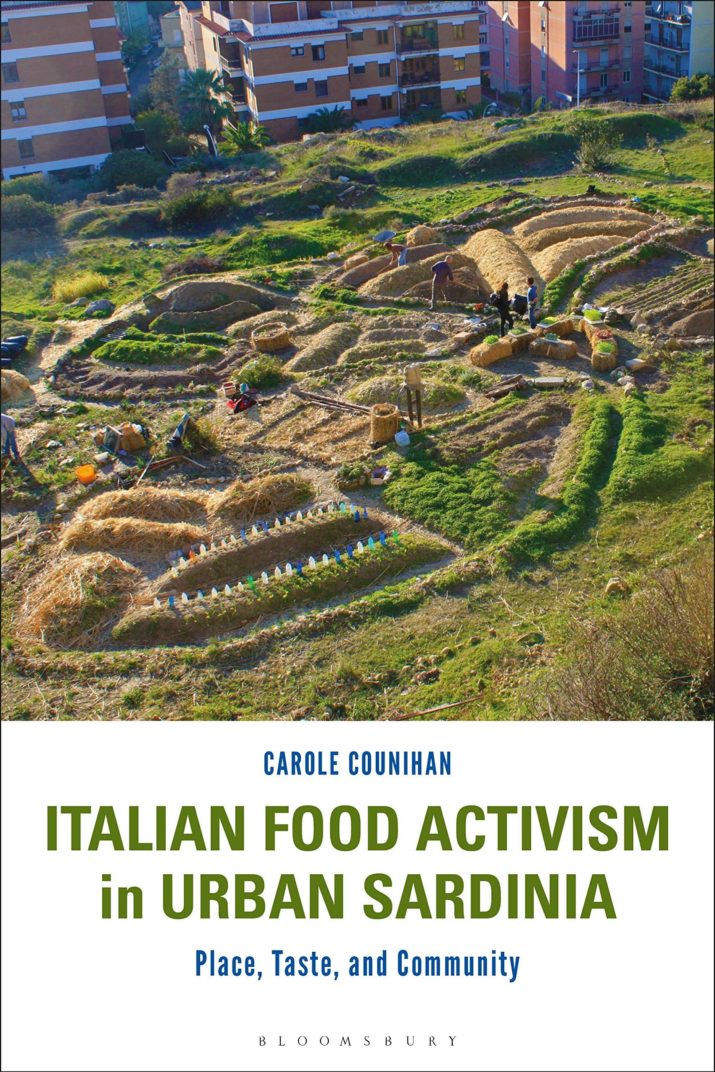

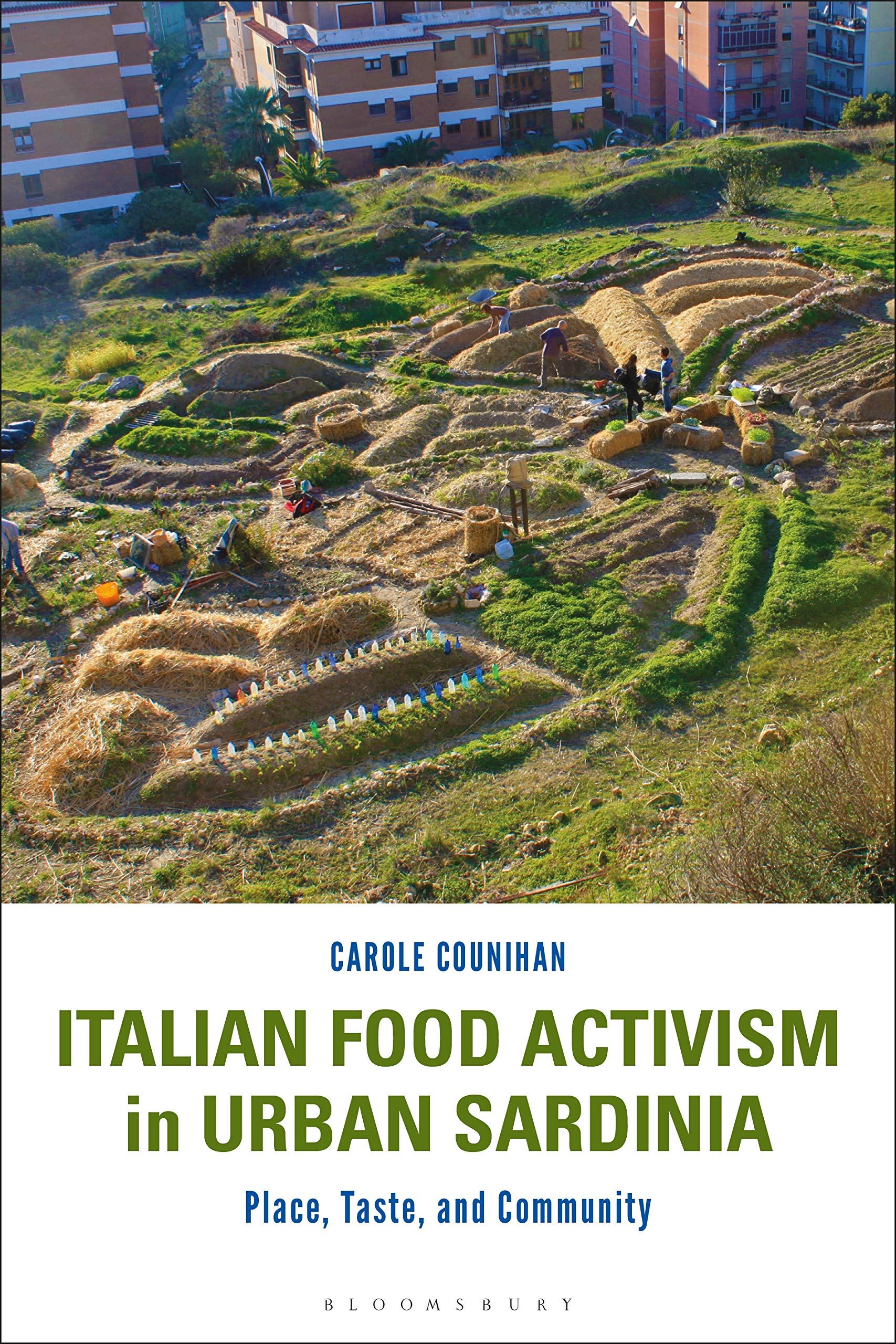

Carole Counihan explores food activism in southern Sardinia. She investigates the work of food activists living in Cagliari, Sardinia’s regional and provincial capital, and its surrounding areas. The choice of Cagliari as the fieldsite for this ethnographic research is dictated by a significant presence of food activism in this area of the island. The study investigates the work of men and women who, from 2011 to 2015, worked in the field of organized alternative food practices or AFN (Alternative Food Networks). Lucy Jarosz has explained that these networks work in reducing the distance between producers and consumers, contrast large scale industrial productions, favor organic and socially and environmentally sustainable agriculture, and use local networks of distribution (2008:321).

The book covers a variety of experiences related to food activism: associationism, food production, food businesses and services, and food education, among others. Counihan, drawing on her previous works with Siniscalchi (2014), defines food activism “as consisting of public efforts to promote social and economic justice through food” and food democracy (3). One of the strengths of this work is its ethnographic approach that emphasizes the work of activists and their experience. The study points out the pioneering and combative spirit required in pushing forward practices that are aimed at contrasting the overbearing power of agro-industrial farming and the often insurmountable obstacles erected by Italian bureaucracy. The testimonies of food activists engage the reader and exemplify the theoretical concepts framing the presentation of each chapter and case study.

Counihan categorizes people involved in food activism as either “food activists,” who push for change in food production and consumption in a militant and organized way, “food advocates,” who work for change inside the institutions, and “food rebels” who are more sporadically and less systematically involved in food activism (3). This classification is, as suggested by the author, somewhat fluid. It falls into a continuum in which those terms are often interchangeable. In fact, food activists can wear many hats. Their role changes depending on the circumstances; one function does not exclude the other, and frequently, a blending of the three roles occur. A food advocate can be at once a food rebel and a food activist. The testimonies presented in the study prove how multifaceted food activism is. However, I find the broad definition of food activism presented in the opening of the study somewhat problematic when applied to the case studies presented. It seems to me that not all the examples discussed fall into such a definition of food activism, or at least they do not exactly comply with the ideas of “social and economic justice” that the definition conveys. In particular, many of the experiences of food activism presented do not focus on social and economic justice, but rather on the rediscovery of local products, traditions, and identity. I am referring here to young farmers working on the production of wine made with autochthonous grapes, or the works of restaurant owners rediscovering local products and recipes. The impact of the work of food activists has possible repercussions on the economy and society of the territory, but food activism in Sardinia is still in an initial, developing phase and it cannot produce any significant change in the Sardinian economy and society. It certainly has the potential to reverse a trend that favored agro-industrial and large-scale production over more sustainable and small-scale businesses, but at present its effects on society and economy are minimal.

Another point that I believe needs clarification is the connection between food activism and organic agriculture. All examples described connect food activism with organic food production and I wonder if food activism can be separated from organic practices or rather if they are constitutive of the work of food activists. Moreover, it would have been interesting to see some references to studies that bring into question the real sustainability of organic agriculture, which requires more extensive use of the territory, since organic products and crops freed from chemical products and genetic engineering produce less and consequently generate larger soil consumption. Organic agriculture is assimilable to subsistence agriculture, which in the past, and especially in Sardinia, has not produced wealth, but on the contrary has kept many farmers in poverty for decades. Is food activism based on organic agriculture really promoting social and economic justice?

Food activism has been met with criticism. In particular, some scholars (Allen and Sachs 2007) have highlighted the scarcity of feminism despite the substantial presence of female activists. Counihan does not observe a great discrepancy in the role of male and female food activists; she did not observe overt sexism either. I found this observation particularly relevant in the context of Sardinian society often described as having a strong matriarchal structure. The case studies presented delineate the profile of strong women who embraced food activism and devoted themselves to this cause despite the numerous difficulties caused by the intricacy of Italian bureaucracy, the scarcity of reliable food suppliers, and the diffidence of some Sardinians towards associationism. Moreover, in some of the cases presented, women who decided to focus on food activism as their job, started their businesses with their companions and ended up having to manage their activities alone as the hardships of making food activism a source of revenues contributed to the deterioration of their relationships. Some of these women were able to carry on with their activities thanks to their extraordinary dedication and hard work. The role of Sardinian women in food activism on the island appears rather significant and might have a connection to Sardinian social structure.

Overall, I find that the key term in the study is territory or territorio in the original Italian. Counihan makes the choice of leaving this word in the original because she finds that the English translation does not convey the same exact meaning as territorio. The scholar remarks that the word territorio is semantically richer and more complex than its English equivalent. This choice is effective as the word territorio establishes a connection with the local culture and identity and it is a crucial element in the process of identity formation. Territorio as an identitarian component is particularly important for Italians who often identify more with their region or city of birth than with the Italian nation. Sardinians, in particular, show a visceral attachment to their island and a strong Sardinian identity. Anna Cossu, one of the activists and leaders of Slow Food in Cagliari interviewed by Counihan, defines herself as “sarda sarda,” or very Sardinian, an identitarian sentiment shared by many Sardinians (20). The use of the word territorio emphasizes the links it has with identity and it remarks its specific relevance, which goes behind its primary meaning. The reference to territorio is present in all the experiences of food activism mentioned in the study; from the work of the local chapter of Slow Food to food entrepreneurs’ businesses. The study highlights how territorio informs the work of many food activists who consider it fundamental in the process of rediscovery of local products and in the safeguarding of Sardinian identity. The revival of all that is Sardinian, from the land to the Sardinian language, is a way for Sardinian people to reappropriate themselves, to come to terms with what it means to be Sardinian, and with the specificity of this island. It looks like Sardinian food activism founds itself on a strong identitarian base that incorporates social and political ramifications. These social and political implications might not be easily grasped by readers who are not familiar with Sardinian history and politics, in particular with self-determination movements that demand greater political and economic autonomy for the island. Counihan makes some references to Sardinian history in the body of the study and in the footnotes, but I believe some more frequent references to central Sardinian political events could have helped the reader to better understand the emphasis given to territorio by Sardinian food activists.

Counihan’s study presents a multifaceted analysis of food activism on the island. She portrays a multiplicity of initiatives, private and public, ascribable to food activism. Although the study inscribes each case study within a theoretical frame, it is very approachable, even for readers who have no background on food activism. The anthropological approach puts at the center of the study, activists involved in a variety of initiatives from the organization of tasting events to the creation of businesses, mostly restaurants and stores that approach food activism from an economic perspective. The work presents a very inclusive idea of food activism, with the term food activist being applied to people active in associations like Slow Food, to activists who work together with the Sardinian government to revitalize and save Sardinian biodiversity, teachers involved in the promotion of traditional Sardinian food, restaurant owners, urban garden promoters, food store owners. Readers who identify activists as supporters of strong actions aimed at changing social and political situations, might not agree with this definition which Counihan use to connect all people surveyed in the study even those who looked at farming Sardinian products as an economic opportunity more than a real engagement with food democracy.

This work introduces the reader to a variety of food activism practices. Each chapter exemplifies food activism theories through the lively testimonies of food activists that Counihan interviewed for her study. The cases presented in the book reveal a strong identitarian component of food activism in Sardinia. This aspect of food activism on the island could be further explored with reference to the cultural and historical specificities of the region.

Giovanni Dettori is a Ph.D candidate in Comparative Literature at Binghamton University. The title of his dissertation is Sardinian and Corsican Literature: Minority Literatures and Identities in Two Western Mediterraean Islands.

Italian Food Activism in Urban Sardinia: Place, Taste, and Community

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Hardcover/ 176 pages / 2019

ISBN: 9781474262286

References

Allen, Patricia and Carolyn Sachs. “Women and Food Chains: The Gendered Politics of Food.” International Journal of Sociology of Food and Agriculture 15 no.1 (2007): 1-23.

Counihan, Carole, and Valeria Siniscalchi. Food Activism: Agency, Democracy and Economy. (London: Bloomsbury, 2014)

Jarosz, Lucy. “The City in the Country: Growing Alternative Food Networks in Metropolitan Areas.” Journal of Rural Studies 24, no. 3 (2008): 231-244.

Published on April 28, 2020.