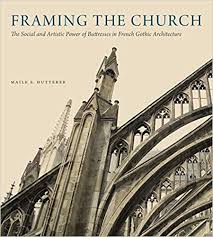

Framing the Church: The Social and Artistic Power of Buttresses in French Gothic Architecture by Maile S. Hutterer

This is part of our special feature on European Art, Culture, and Politics.

Nature abhors a vacuum. As does culture—if by culture we mean the social, economic, and political systems that humans construct. This new book argues that cultural forces co-opted the structures of flying buttresses for a variety of purposes, both sacred and profane. The upper regions of buttresses became ecclesiastical “billboards” to assert the authority of bishops and the sacrality of the liturgy, while at ground level the rectangular compartments between the projecting masonry piers could be closed and put to use either as outdoor shops or as additional chapels accessible from the interior. Spectacle and ostentation were very much part of the story here, as well as more mundane matters such as getting and spending.

This ambitious study explores the aesthetic, symbolic, and economic roles of the flying buttress within the sacred and profane spaces of medieval cities in France. It is a transverse examination across a series of major cathedrals that examines buttresses as sites of social and economic action and display. The projection of buttress supports outside the containing “envelope” of a church wall make a strong visual statement that became a central characteristic of Gothic architecture, creating what the author describes as a “three-dimensional choreography of void and solid, light and shadow, that endowed the outer shape of the church with increased plasticity and drama.” In addition, the visual impact of the flyers in the upper reaches of a cathedral radically transformed their exterior appearance, enabling the creation of taller, lighter, more strikingly visible buildings that projected over an urban landscape. High up at their apex, the sweeping curves of flyers generated complex visual patterns that, combined with the new surge in gigantism, transformed medieval cities and asserted the primacy and authority of bishops and archbishops at a time of profound social, economic and political change—change that was often challenging precisely this authority. Because of their scale and visibility, the flying buttress became a visual symbol of sacrality: two-dimensional patterns representing the transverse section of a church with the broad curves of the flying buttresses were as a result adopted as decorative and framing elements in manuscript illuminations, episcopal seals, reliquaries, choir screens, stained-glass windows and even tombstones, as shorthand for the sacred.

The book is about cathedrals “having their cake and eating it too:” below, at street level, the rectangular compartments created by projecting buttresses generated income as rented shops, while in the lofty regions above the clergy could assert their authority and the sacred character of their mission, a mission that tended to disdain the very sources of the cash income upon which religious institutions increasingly depended. In some cases (Laon, Paris) the revenue generating spaces between buttresses were instead absorbed into the interior of a cathedral by demolishing the original enclosing wall and constructing a new one at the outer edge of the supporting piers, thus creating chapels that could be adopted by donors, lay or clerical. These chapels also, however, were part of an economic system, as they generated substantial income in the form of bequests and donations to the church. So below there is money; above there is the detached and ethereal realm of sacred authority.

The volume moves through a wide range of topics, starting with the forms and aesthetics of flying buttresses, the social and economic factors that determined the use of the spatial compartments they created, and the role of flyers as political gestures and ideological instruments. Hutterer emphasizes the extent to which flyers transformed the appearance of religious architecture by noting how this structural system generated new patterns of light and shade, creating a complex, ever-shifting, exterior armature for a cathedral. In a closing chapter, she develops analogies with defensive architecture, noting that the upper walls often quoted symbolic versions of defensive systems, such as crenellations, and that the fanciful and terrifying figures of gargoyles played an apotropaic role, defending the church against evil. Since so many studies of Gothic focus on the design and history of individual buildings, it is salutary to be reminded of the radical transformation of both architectural structure and urban landscapes that were introduced by the Gothic structural system. Furthermore, comparative case studies of several buildings demonstrate that well into the Renaissance (for example at Saint-Eustache in Paris or Saint-Jean-au-Marché in Troyes) aesthetic considerations could take precedence over structural concerns: certain designs, such as the openwork buttress at Saint-Jean-au-Marché, were adopted in spite of the evident failure of the prototype at nearby Troyes Cathedral. The fact that aesthetic concerns prevailed over good sense and structural stability attests to the symbolic importance of these highly visible architectural forms.

The rectangular spaces created by the projecting support walls at ground level were liminal zones between sacred and profane, and their social and economic potential rapidly became evident. Each cathedral, however, presented a different and possibly shifting approach to the use of these compartments, sometimes determined by property ownership, financial expediency or the ability of the ecclesiastical administration to negotiate the acquisition or control of adjacent property. In Reims, for example, the cathedral treasurer had control of a thin slice of land on the north side of the nave, and his obstinate defense of his turf may have inflected the fate lateral spaces on that side of the building.

The financing of cathedrals and their relationships to the surrounding urban environment are deeply interesting and complex topics; each situation was unique and each cathedral and its clergy had a different relationship to its city. The arrangements of buttress compartments highlight the increasing engagement of cathedral administrations in an overt cash economy even as they disdained the merchants who carried this economy forward in their markets and shops. Long ago, the topic was marvelously explored by Henry Kraus, in his volume of 1979, Gold was the Mortar: The Economics of Cathedral Building, a volume not discussed by our author but of pivotal importance for the topic. Kraus was among the first to address the broad range of the social and economic consequences of cathedral building and to engage with the implications of the vast expense of such enterprises over the long term. (In this regard, it may not be irrelevant that he had been a labor organizer whose move from the US to France in 1956 may have been a delayed response to the McCarthy hearings.)

However, the uppermost regions of flyers, in particular those of Chartres, Reims and St.-Quentin, heavily damaged in World War I bombardment, lift us out of the world of commerce and into celestial hierarchies. In the early decades of the thirteenth century, Chartres set the stage with its monumental statues of bishops inserted into the upper buttress piers. At Reims a multitude of angels placed high and low in the buttresses, many of which carry symbols of the Passion, are described as guardians of the Heavenly Jerusalem and metaphors of the sacred and divine rituals of the liturgy performed within the church.

Hutterer’s discussion is genuinely interesting, and she cites the relevant literature. Yet the discussions of Chartres and Reims in particular tend to elide the granularity and complexities of each local situation: both were sites of severe urban contestation between townspeople and the ecclesiastical hierarchy. There were battles in the streets, accusations of usury, persecutions for heresy, and at Reims the canons and archbishop had to flee for twenty-six months. At Chartres, the disputes also entailed the contested rights of the count, whose palace was a few hundred meters below the south flank of the cathedral. During the decades of its construction, Reims Cathedral was in the process of asserting its absolute right as the site of royal coronations, a tradition that continued with some vicissitudes until 1825. What better ways to assert the rights of ecclesiastical authority at Chartres, or to the sacred and ancient ritual of coronation at Reims, than to decorate the most visible part of a cathedral with statues of bishops as authority figures (Chartres), or angels to identify and contain the notion of sacred space and ritual (Reims)? At Reims, moreover, the angels of the exterior of Reims assert the divine nature of the liturgy while the rigid hierarchy of the archbishop’s authority is manifest in the magnificent stained-glass windows of the chevet interior.

Framing the Church is a provocative and stimulating book, one that is best-suited to historians of art and architecture. But it is also, on some level, too ambitious; it takes on the fluctuating histories of too many sites and bends the evidence to support several theoretical concepts that either override, or exclude, the fragmentary and shifting evidence of each place. Each cathedral had its own long story, and although the overview is interesting and important, many of the finer details have been lost in the shuffle.

Caroline Bruzelius is a scholar of medieval architecture and sculpture in Italy and France. She has published extensively on Gothic buildings and taught at Duke University from 1981 to 2018. Between 1994 and 1998, she was Director of the American Academy in Rome. She now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Framing the Church: The Social and Artistic Power of Buttresses in French Gothic Architecture

By Maile S. Hutterer

Publisher: Pennsylvania State University Press

Hardcover/ 207 pages/ 2019

ISBN: 9780271083445

References:

Kraus, Henry. Gold was the mortar: the economics of cathedral building. Vol. 30. Routledge, 1979/2019.

Published on April 28, 2020.