Translated from the Italian by Stephen Twilley.

This is part of our special feature on European Art, Culture, and Politics.

June 9, 1948. Mme Cli Laffont has invited me to dinner at her house this evening, to meet Albert Camus.

It’s hot out. Paris is wrapped in a shroud of heat that lifts the houses into midair, like in Chagall’s dreams.

Mme Véra Korène is expecting me in the bar at the Plaza, to introduce me to some of the Brazilian friends she met during her long and painful exile in Rio de Janeiro. Her Brazilian friends are tall, thin, sleek young women with incredibly small round heads. They have very small noses, eyes larger than life, high and narrow foreheads, very narrow mouths, transparent ears, skin coated with that dull splendor that faces have under the moon. They move slowly, lazily; move their arms or turn their back by swiveling their chest, their head immobile, with the lazy litheness of reptiles. Amid that group of young and very beautiful women, women of strange beauty, Véra Korène looks like a Doric column. She reminds me of a solitary column at Delphi, in the white light of Delphi. Véra’s voice is very beautiful, the most beautiful voice in Europe. She calls to me from afar, smiling, her mouth slightly open. Beside her, nearly hidden by the very beautiful Brazilians, is a prince of Braganza, I don’t know which, or why he’s there: pleasant, smiling, discreet, timid. I’ve always had the impression, face to face with this species of young and very beautiful women, that they have genitals in their armpits. When they raise their arms, through the black tuft gleams something rosy, deep, and moist that makes me blush, makes me dizzy. I notice that they’re upset by my gaze, which slips insistently to the hollow beneath their arms. But I’m upset as well, by possessing them all there, in public, in the bar of the Plaza. There’s one, sad and mean, with her eyelashes half lowered, who looks at me with insistence, leaning an elbow on the bar, a glass clutched in one slight fist, the other arm resting along her body. I say to Véra: “I like that girl. Why don’t you ask her to raise her arms?” The girl smiles, and slowly, staring at me through half-lowered eyelashes, slowly raises an arm. I have never seen a woman spread her legs with such wickedness. Something rosy, deep, and moist appears among the curly, glossy black tuft. Smoothing her hair against her neck with one hand, she stares, smiling. I say to Véra, “Let’s get out of here.”

It was already late and Véra hailed a taxi, running after it along the sidewalk for a long stretch. I jumped in the taxi and saw Véra standing at the edge of the sidewalk, solitary and mild. When I got to Cli Laffont’s, Albert Camus was already there, seated on a sofa between two young women. I immediately noticed that he was looking at me with hate. He had an unremarkable tie and an unremarkable hate. I immediately strove not to judge him by his tie, but by his books. Not to pay him back in his own coin. I am always sorry to encounter incomprehension, hate, sectarianism. I always strive not to put myself on the same level as someone who stands before me on spurious grounds.

I did not and do not have, nor will I ever have, any reason to hate or disdain a man and a writer like Albert Camus; I have many reasons to be fond, to esteem, and to be grateful for the author of L’Étranger and La Peste. And it doesn’t matter to me in the slightest if he doesn’t love me, doesn’t esteem me, and perhaps hates me. It’s his business.

I was persuaded, in that moment, that he had nothing better to do than look at me with hostile eyes. I had been told he had no affection for me, and that surprised me, coming from a writer like Camus; it seemed to me not worthy of a man of talent to judge a man without knowing him. For this reason, maybe, I went to him with the unconscious aim of winning him over. I was surprised not only that Camus made no impression on me, but that I didn’t feel inclined to win his affection.

I recall that, at a certain point, someone having asked me what kind of man was Bottai, the former Fascist minister, etc., Camus said sententiously that such men should be dragged before a court, and then shot. I didn’t like this brisk manner of understanding justice, and I asked Camus what made him think Bottai should be shot. Camus, without looking at me, replied that all these men, assassins, etc., should be shot. I replied that not only was Bottai no assassin, he was in fact quite incapable of hurting a fly. But I understood very well that Camus wanted to imply that I too should be shot. This absurd idea made me laugh, coming from a man like him. And I was astonished to see how casually many people judged others without knowing them. I would have liked to respond that, if he wanted to shoot Bottai, let him first try to shoot the many Bottais that exist in France as well. But I kept quiet, not seeing a need to give weight to the words of a man who spoke under the influence of a preconceived hostility, and just to give himself the air of a Saint-Just.

For the entire evening Camus behaved like a man deeply offended by I don’t know what, and I thought that that behavior failed to impress even the ladies, and that it was proof of scant intelligence. But since Camus is an intelligent man, I could not attribute such willful severity to anything but a desire to appear pure, intransigent, heroic, resolute, severe, a ridiculous desire if that’s what it was. Etc., etc., etc., etc. I would have understood Camus wanting to shoot Bottai, if the latter had been a writer, it being the deep-seated wish of every writer to have other writers shot. But Bottai is not a writer; therefore, he could not provoke a shred of jealousy in a Camus. I thought that Camus, as a writer, wanted to shoot everyone who wasn’t a writer, and this idea also seemed strange to me, because we would before very long find ourselves living in a world without any writers, without anyone who wasn’t a writer, populated only by a Camus resplendent in his unique, solitary glory. But I abandoned this idea as well, as preposterous. And I concluded that perhaps Camus was alluding to me, only to me, out of jealousy as both a man and a writer. Now, I am a puny writer in comparison with a Camus, and as far as male jealousy goes, I am not such an Apollo as to compete with a Camus. And I settled on the idea that Camus wanted to have me shot to prove to himself his capacity for heroic acts, etc. And I imagined the scene: me blindfolded, tied to a chair or a stake, and Camus alone before me, with a rifle in his hand, a steady gaze, an expressionless face, a bare head. I pictured him taking aim for a long time, squeezing the trigger, and missing the target. And then I would have gotten to my feet, and I would have said to him, etc.

I saw Camus in that heroic attitude that evening, and so I will always see him: armed and alone, ready to shoot a man whom he didn’t know, a man who had never done him any harm and who in terms of fashionable rhetoric found himself in much better conditions than him. And I wonder what the hell Camus ever did to have the right to shoot others.

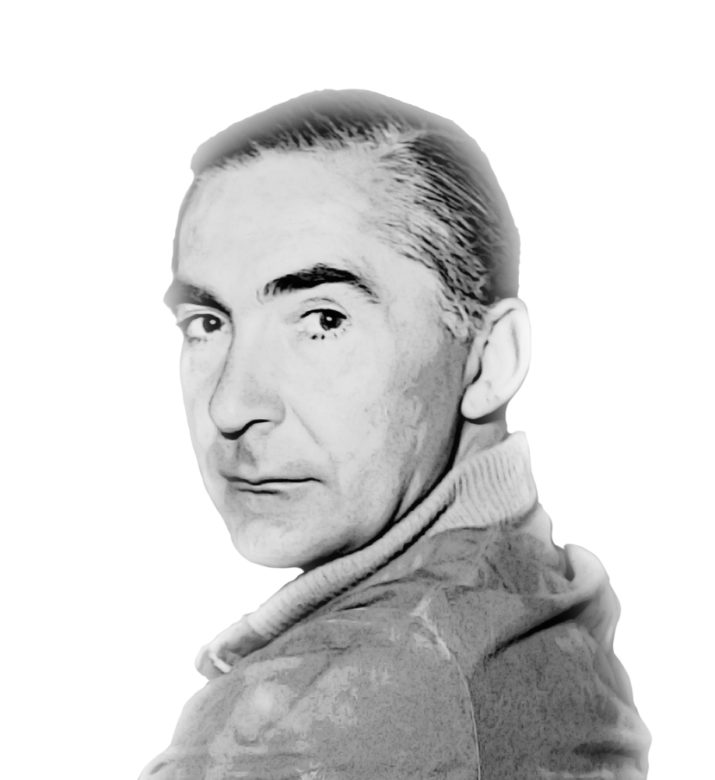

Curzio Malaparte (pseudonym of Kurt Erich Suckert, 1898–1957) was born in Prato, Italy, and served in World War I. An early supporter of the Italian fascist movement and a prolific journalist, Malaparte soon established himself as an outspoken public figure. In 1931 he incurred Mussolini’s displeasure by publishing a how-to manual entitled Coup d’État: The Technique of Revolution, which led to his arrest and a brief term in prison. During World War II Malaparte worked as a correspondent, for much of the time on the eastern front, and this experience provided the basis for his two most famous books, Kaputt (1944) and The Skin (1949). His political sympathies veered to the left after the war. He continued to write, while also involving himself in the theater and the cinema.

Stephen Twilley is the managing editor of Public Books. His translations from the Italian include Francesco Pacifico’s The Story of My Purity and Marina Mander’s The First True Lie, and for NYRB Classics, Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Professor and the Siren. He lives in Chicago.

This excerpt is published by permission of NYRB Classics. Copyright © Curzio Malaparte. English translation copyright © Stephen Twilley 2020.

Published on April 28, 2020.