This is part of our special feature, Me Who? The Audibility of a Social Movement.

Translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel.

We turned fourteen that spring, Bella, Momo, and I. We kept to ourselves. In winter we were mostly in Momo’s room but during the hot time of year we kept to Bella’s garden, or the greenhouse when it rained.We listened to the insects and to the rain, watched the droplets on the petals evaporate when the sun broke through. Curious, we watched the flower flies mate in the oxeye daisies—a strange and violent dance that sent shivers through the thin petals. During dry spells we watered at night. Bella filled the green can over by the house and we helped carry it across the lawn. She never asked us to help but neither did she stop us, wordlessly showing us what to do. She knew the names and types of flowers but she rarely shared them and I didn’t ask, it wasn’t important to me. Her flowerbeds dazzled like New Year’s fireworks and like all fireworks they were best at night, when the streetlights’ soft yellow glow spread through the neighborhood.You might have thought the velvety leaves would close up when it was dark but they didn’t.They opened up to the night, screaming at the stars:

I’m over here! Look at me! The night is black BUT I AM IN COLOR! We lived amidst this sparkle and it made me forget that I was Kim, that I had a growing, bursting body.The greenhouse was a free zone, a space governed by other laws.The school days and hallways and my parents’ house—everything fell away when I walked through that glass door. Even Bella became someone else in there. Her eyes were calm and sharp as a knife, her movements were precise and confident. At school she was a chubby girl with red hair and freckles, a girl who preferred to sit quietly and stay invisible for as long as possible. And me, I was a sad skinny thing with lanky legs and an oversized head. My skin flamed with eczema as soon as it came in contact with any unknown substance—I couldn’t handle the hot summer sun or cold winter winds, nor could I eat red tomatoes or golden oranges.They gave me a flaming rash around my mouth and nostrils, and I would have to rub stinky ointment into my skin for days in a row. My girl-skin preferred paper-dry air and wallpapered walls, strip lighting and linoleum, and chlorinated water.

I hated it.

My body clung to me like something foreign—a sticky, itchy rubber suit; but no matter how much I scratched and scraped at it, it was where it was. At night I dreamed of shedding my body. It was so simple, suddenly a zipper appeared in my skin. Sometimes it was along my inner thigh, sometimes across my stomach, along my back or between my legs. I opened it, I could feel the air flowing toward my real skin underneath, like a vacuum seal breaking. And I peeled off my skin, climbed out of it like a soiled garment and I could feel the cool floor against my new soles. But before I could get to the mirror and discover what I actually looked like, I’d wake up.

I told Bella about this dream once, while she was culling her red flowerbed. I was crouching down next to her, handing her the spade and the hand rake, and I told her exactly how it felt—what it was like when my skin loosened and fell off me. Bella had dirt on her face, a blade of grass at her hairline, and she listened earnestly. She didn’t say a word, but I knew she got me.

Yes, we turned fourteen that spring and we hid in the greenhouse to avoid growing up. We stayed away from people our own age, we were wary of heeding the call of the hormones in our blood because we suspected that they could overpower us at any time, without our consent. We knew what was waiting for us: one morning we’d simply get out of bed and know that the time for children’s games was done. We’d look around, see what everyone else was doing, and do the same. Learn to drink, smoke, kiss. Learn to tolerate boys touching us.All we would have to do would be to walk straight ahead, putting one foot in front of the other until our ankle muscles were strong enough so as not to twist when we wore slender high heels.

We didn’t want to, Bella, Momo, and I.

We refused!

Our bodies wailed and writhed, we itched with restlessness. We walked around like large irate animals in our parents’ houses, shouting for something that could still the strange swells, but wherever we looked we all we saw were ready-made Female Models. We shut our mouths and closed our eyes, refusing to accept the inevitable. It was instinctive, an ember in the chest: anything could happen to us—just not that. So we fled to the greenhouse, turned away from the world, sought comfort in the earth and the flowers and the insects.

School days were made up of combat strategy and clashes. People crowded in the hallways, girls with girls and boys with boys. We practiced making it look like we were completely consumed by what was happening in the group.We listened to the person talking or showing off or taking center stage in some other way; meanwhile, we kept an eye on the halls: who was coming and going, where they were walking, what their expressions were communicating. Because it could happen at any time, anyone could make a not-insignificant gesture, a not-insignificant sound with their tongue, or take a not-insignificant step in our direction.

It happened all the time. Some boys would walk past some girls and right when they were in line with each other one of the boys would stick his elbow to his crotch and shoot his forearm up like an erection. He’d tense his arm, squeeze his fist, mimic the sounds he’d heard in the movies he watched with other boys.Another boy would note this gesture and start stabbing his tongue at the inside of his cheek.Then they’d let out a collective howl, and a deluge of fleshy porn dialogue would be unleashed on the girls.

There was only one way to respond: keep your mouth shut and head held high; keep your mask intact even though those words and gestures always got under your skin. Mostly we weathered it.We fixed our eyes on each other and whoever was talking would forget what she was talking about, but she kept talking anyway. We encouraged her with nods, soundlessly we convinced each other that “It’s okay, don’t worry about them, don’t turn around, keep talking, don’t show them you’re afraid, for God sake don’t show that you’re afraid.”

But sometimes the crowd of boys approached with something unyielding in their eyes, when we were specially chosen and they circled us, standing close, so close their breath built a wall in front of our faces and it was impossible to turn away because they were everywhere.They licked our cheeks with the tips of their tongues, searching for our lips, their boy-hands ran up our thighs and they whispered things, rumbling false declarations of love in saccharine tones.And if you managed to keep your mouth shut the whole time, if you kept your eyes fixed on the ground as they probed you with their hands and tongues, then it would end with a shove to the chest and a loogie at your feet. Before they’d turn their backs on us, they would hiss about what disgusting, ugly cunts we were, so fucking disgusting no boy would ever want to fuck us even if he got paid to do it.

We kept our mouths shut, counted backward in our heads to keep still while waiting for it to pass. But sometimes it burst.Then we hissed back at the boys, Momo, Bella, and I.We hissed at them to leave us alone, trying to tear ourselves from their grip, spit in their faces, knee them. But they were so much stronger; hopelessly, unfairly, unbelievably stronger.All they did was laugh at us, grab us by the wrist and smile at our tiny balled fists. It was them and only them who could decide when the game was over.

I couldn’t handle it. I hated them. I could endure any and every humiliation, if only I didn’t have to deal with those double-edged, backhanded signals directed at us alone, at us girls. The dripping saccharine lines, their hands nonetheless hot against our bodies, their crooked smiles that in spite of everything made something flicker in our chests, only to be tossed aside and spit on, proving just how insufficient and disgusting we were.

At night I lay awake and tried to shut my eyes to what was happening. I tried to forget their hands and their gazes and their breath and I frantically tried to figure out how to rid myself of what provoked them. I daydreamed about revenge, I was large in those dreams, large and tough and strong and my voice was deep. I bellowed at the boys and my voice made their hair blow backward, my saliva showered their cheeks. Then they ran, and I lumbered along like a giant, a hero in the hallways.

But in reality I wasn’t large and tough, I was thin and lanky and there was no way to rid myself of what provoked them.

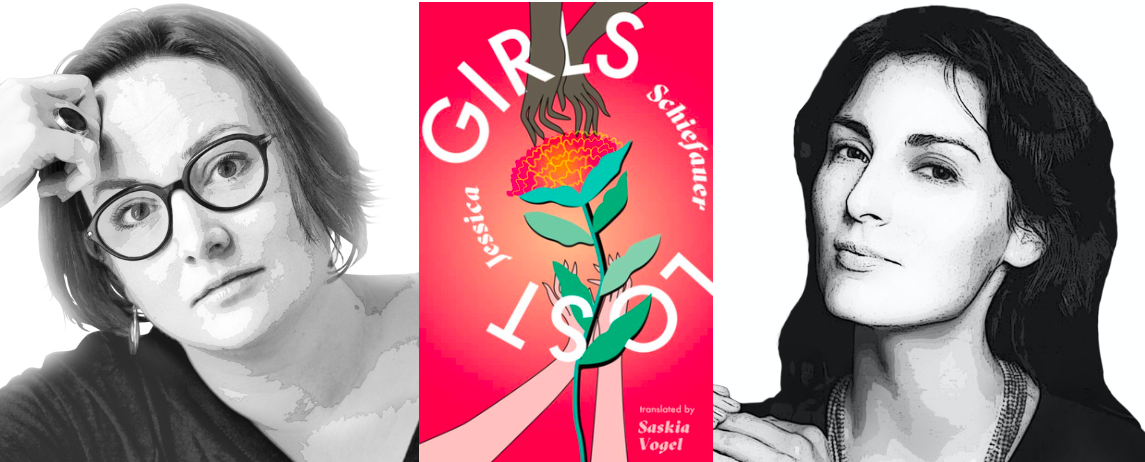

Jessica Schiefauer has established herself as one of Sweden’s foremost writers of literary young adult and adult fiction. She has won the August Prize twice for her books Girls Lost and The Eyes of the Lake. Her books have been translated into several languages and adapted into theater and film. She has contributed short stories to the erotica collection Hot (2012) and the science fiction collection Other Ways: Ten New Utopias (2015), among others. Schiefauer holds a teaching degree in Swedish, English, and creative writing. She lives in Gothenberg, Sweden.

Saskia Vogel is from Los Angeles and lives in Berlin, where she works as a writer and literary translator. She has written on the themes of gender, power and sexuality for publications such as Granta, The White Review, The Offing, and The Quietus. Her translations include work by leading female authors, such as Katrine Marcal, Karolina Ramqvist and the modernist eroticist Rut Hillarp. Previously, she worked in London as Granta magazine’s global publicist and in Los Angeles as an editor at the AVN Media Network, where she reported on the business of sex work and adult pleasure products. Her novel, Permission, was published by Coach House Books in 2019.

This excerpt of Girls Lost is published by permission of Deep Vellum Publishing. Copyright © Jessica Schiefauer, 2011. English translation copyright © Saskia Vogel, 2020

Published on March 11, 2020.