This is part of our Campus Spotlight on Appalachian State University.

This is part of our special feature, Me Who? The Audibility of a Social Movement.

Last week, my oldest dog was diagnosed with late-stage congestive heart failure. As she struggled to eat and even to breathe, my partner and I juggled the timing and administering of her growing numbers of medications, both pharmaceutical and herbal, trying in the meantime to focus on work and household duties. There were no days off from our jobs, no casseroles brought by friends and neighbors. Yet, someone in our household was dying, and the questions were not so different for a beloved dog as for a human being: how to let go and when. Annie wasn’t getting regular doses of morphine as my mother did; we were still trying to give her a few more months. But her labored breathing, her days of only a spoonful of food, and her sad, dark eyes told us it was time to part.

As an ecofeminist scholar and poet, I write about other animals, individual animals, because their lives matter. That mattering always unfolds within the larger multi-species world I inhabit, in particular my home in the hardwood cove of red oaks, sugar maples, buckeyes, and beeches where I have been lucky enough to live for almost three decades. This region in the Blue Ridge mountains of North Carolina is one of the most ecologically diverse on our planet, and the flora and fauna of my adopted Appalachian home populate many of my poems.

As well as a practicing poet, I am also trained as a materialist feminist scholar. I was raised by parents who grew up poor, and I understand intimately that the material conditions of a life matter. Moreover, my childhood was also nomadic, sensitizing me to questions of place and belonging. The climate my father established in our family seemed to come down with his surname from the Scots lowlands and borderlands by way of the Ulster plantations in Ireland. Our weather was changeable, tempestuous, quarrelsome. Some days, it’s hard not to feel that the trauma of ancestral displacements reverberates in my bones. Small wonder, then, that when I’ve undertaken literary and cultural studies projects, I’ve written about women, particularly Irish women, in the contexts of property rights, contested land, disenfranchisement, and class trauma.

This dual vocation of academic and poet has felt both necessary and arduous: in the 1980s, reclaiming women’s writing through scholarship felt like putting literal ground under my feet. From that ground have grown poems, and then collections of poems, seven volumes to date, informed by living in a place I have come to love deeply. The Fisher Queen: New & Selected Poems gathers what I hope are some of the best. The character I created to frame them speaks from the Parzival legend: “that’s where they found me, / beyond the usual margins, / in the hinterland of the old text / camping out on the Grail castle grounds / with my solar oven and organic greens.” I wanted a voice irreverent and strong, nimble on the margins. Like other women before me, I’ve found green spaces for both my life and my poems, all the while realizing that the patriarchal structures of the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene leave no place untouched in our emerging era of climate crisis. The Parzival legend unfolds in a wasteland, after all: “I tell you this now because / you’ve got your own wasteland / and you’ll need help / from unexpected quarters,/ new pages for the story.”

Inhabiting a woman’s body and spending weeks in classrooms and archives made me a feminist scholar; living in this cove with hawks, deer, owls, coyote, and possums, I became an ecofeminist. Each day when I walk the ridge I try to know the land and other creatures, hoping that what I learn might speak up in the poems.

Annie learned our mountain ridge relatively late in her life. When we adopted her, we knew only that she had lived some of her eight or nine years in a garage. We learned later, from her confident, brisk stride on sidewalks and asphalt, that she must once have been loved by a suburban walker. Our mountain trails were harder for her. She had clearly not done much hiking, and she sometimes lost her footing on our ridge, careening down a slope too fast. But slowly she learned to understand depth and drop, to stay upright in the winding rush down our trails to home.

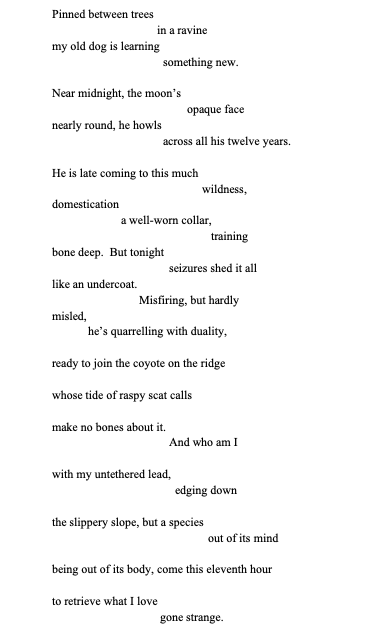

Annie is only the third dog I’ve seen to life’s end. As a lower middle-class kid raised among enlisted families in the Air Force, I lived from posting to posting, country to country, only briefly with dogs, who often had to be left behind or given away. I’ve treasured the dogs of my adulthood, seeing most of them through from puppyhood to old age. Before Annie, there was Beamish. The poem “Millenium,” grew from nursing him through his last months, which were jarred by epilepsy.

Affected like the tides by the moon, the dog’s altered neurology in this poem tends toward rewilding. The narrator’s authority slips as neutral description becomes radical self-doubt. As in many of my poems exploring relationships with non-human animals, here the narrator is as much in need of rescue as anyone else. At the end of the poem the particular becomes communal with “who am I / . . . / but a species / out of its mind / being out of its body,” the speaker attempting to name another kind of mind/body problem, disassociation from the reality of climate crisis that we are all currently living. Is this the historical moment where Cartesian dualism has landed us, our disembodied rationality untethering us from effective action in the face of a planet we are rendering uninhabitable? The experience of caring for my ailing dog as he himself short-circuited across his brain’s hemispheres compelled me to ask this broader question.

The dignity of dogs when ill and dying is instructive. Annie refused the heart meds we coaxed her to take, then clamped her teeth tight against any attempt to push them down her throat. Pleading helped: I think she took the huge Vetmedin tablet more than once to please me. But she seemed to know we were past intervention, and after a few miserable struggles, we took her point. She licked baby food from my fingers, mouthed steamed chunks of sweet potato. That last morning, eager to be let out, she caught my eye as I watched from the window. I was already grieving.

As well as dogs, I have mourned the lives of house wrens and deer in my poems, wailed with neighborhood cows whose calves have been taken and sold. In order to do this, I had to re-embody myself. To fully embrace our own animal bodies is to reclaim our kinship with a multi-species world. When I look back at some of the titles of my poetry collections, I can see that embodiment has always been a focus: The Body’s Horizon (1996), Beyond Reason (2004), Our Held Animal Breath (2011). Early in my graduate student career, I studied the work of the nineteenth century English feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, arguing that in her two Vindication volumes she’d restored the faculty of feeling to the unfolding of reason. Wollstonecraft was working to dismantle disempowering dualisms—reason/feeling, mind/body—through her work. So was I: as a woman earning a PhD in the mid-1980s, I felt that the academic enterprise asked me to leave my body. My class background added to my feelings of dislocation. When I read Marx, Delphy, and Kollontai, the tools for class analysis and then a feminist class analysis became mine. And yet my growing understanding of the material conditions of women’s lives wasn’t complete. The ecofeminists who might have helped me, writers like Marie Mies and Vandana Shiva, Carol Adams and Greta Gaard, hadn’t arrived on the syllabi in my feminist theory classes. And so, years later, I was, ironically, led to the bodily knowledge I needed by illness, dis-ease become disease.

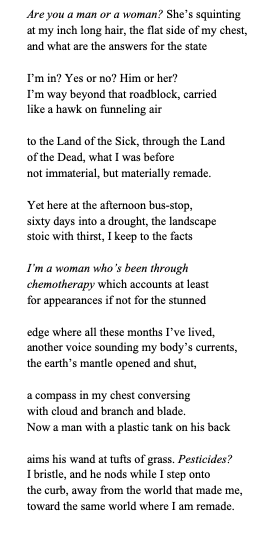

The poems in my fifth collection, Unaccountable Weather (2011), track my experience of breast cancer treatment. Some of these poems are reprinted in The Fisher Queen, the wounding now a part of her story too: “Given the ways the story’s been told, / you’d think the King’s was the only wound. / But I lost one of my breasts in that battle / for static perfection, the small pear of the other / I’d like to keep.” Since there’s hardly a mention of a queen in the medieval romance, Parzival, I was free to give The Fisher Queen a role in the legend: like her husband, she’s been seriously wounded and her recovery, like his, is bound up with the healing of a wasteland. The legend intersects with my own in a poem like “Alter”:

This poem opens with a narrator whose body has been altered by mastectomy; though she calls herself a woman midway through the poem, the identity is one she’s pressured to re-inhabit by an unknown interlocutor, and she makes the choice to shut down the interrogation by naming the new category, if not gender, to which she belongs. Having undergone an otherworldly passage where the usual identifications no longer hold, the narrator is more interested in the bonds she shares with the environment she inhabits. In this drought stricken landscape managed by chemicals, she recognizes the source of her illness and the terms of her adaptation to a wasteland. The man with the wand performs a magic she resists, but in Donna Haraway’s terms, she must recognize that she too is cyborg now.

In the three years we lived with Annie, we learned to take at least one other dog with her to the vet or groomer so that Annie would be persuaded we weren’t going to leave her behind. Each car journey was fraught as she panted in an anxious fidget. When she finally arrived back home, she’d twirl into the living room, barking with excitement. We couldn’t know the memories of trauma those car rides triggered, but they told us something about the resources she plumbed as she lived out her daily resiliencies with us. Her willingness to make a go of an entirely new life in her last years inspired and moved me.

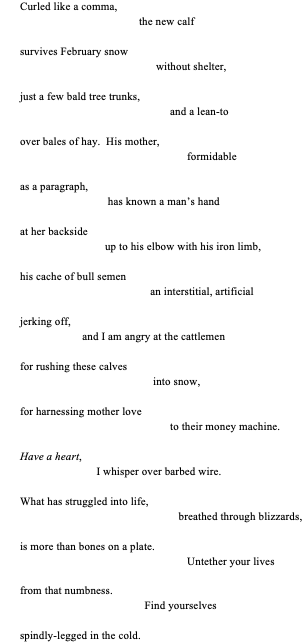

Newly aware of my own vulnerable animal body, after my illness I stopped eating animals. I could no longer ignore the bodies of cows and chickens, pigs and sheep who lived and died miserably so that I could satisfy a craving. When I learned that consuming their bodies might even have helped to promote the cancer initiated in my breast, the choice was clear. Still later I discovered the devastating impact of animal agriculture on the world’s forests, water systems, and climate. Like the Fisher Queen, I had found that the health of my own body was tied to planetary health: the wasteland was in me. Working to heal myself would never be separate from working to heal the planet. As part of this process, I read and integrated the writing of ecofeminist Carol Adams, whose The Sexual Politics of Meat (1990), Neither Man Nor Beast (1994), and The Pornography of Meat (2004) articulate the intersectional oppressions between women, other human Others, and nature, including animals. I began to write poems with other animals as the subject of their own lives. “Calf” arose from witnessing in my neighborhood the breeding of cows so that they often gave birth in the dead of winter, their calves exposed to brutal cold.

Carol Adams included this poem in The Carol J. Adams Reader: Essays and Conversations 1995-2015, in part, I think because it works to inspire empathy in readers for whom the cultural norm is commodification of animal bodies. Moreover, the poem names the economic system that exploits female animals for their reproductive capacities, entreating human actors to intervene and carnist readers to cease to be complicit. Living as an ecofeminist in the Anthropocene, I can’t make poems do my bidding; but after ten years of poetry practice as a vegan, I am sometimes visited by what I imagine the land and the other animals would have me say. Annie has come home one last time, and she rests now in the side of our mountain ridge. Beside me in spirit as I’ve written, she was quite certainly the subject of a large, grand life. I am honored to have shared her last chapters.

Kathryn Kirkpatrick is Professor of English at Appalachian State University where she teaches and writes about environmental literature, animal studies, and Irish studies from an ecofeminist perspective. She is also affiliate of the Gender, Women’s and Sexuality Studies program there. She is the author of seven books of poetry, including collections addressing female embodiment, climate change, human illness, and nonhuman animals (Unaccountable Weather (2011) and Our Held Animal Breath (2012)). The Fisher Queen: New & Selected Poems(Salmon Press, 2019) was recently awarded the NC Literary & Historical Association’s Roanoke-Chowan Poetry Prize. For more about her work go to kathrynkirkpatrick.org

References

Adams, Carol J. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. London: Bloomsbury, 2015.

———-. Neither Man Nor Beast: Feminism and the Defense of Animals. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

———-. The Carol J. Adams Reader: Writings and Conversations 1995-2015. London: Bloomsbury, 2016.

———-. The Pornography of Meat. New York: Lantern Books, 2015.

Delphy, Christine. Close to Home: A Materialist Analysis of Women’s Oppression. London: Verso, 2016.

Gaard, Greta. Critical Ecofeminism. Lexington, KY: Lexington Books, 2019.

Kirkpatrick, Kathryn. “Sermons and Strictures: Conduct Book Propriety and Property Relations in Late-Eighteenth-Century England,” in History, Gender, and Eighteenth-Century Literature, ed. Beth Tobin. University of Georgia Press, 1994, pp. 198-226.

———-. “Going to Law Over That Jointure’: Women and Property in Castle Rackrent.” Canadian Journal of Irish Studies. 22:1 (July 1996): 21-29.

———-. The Body’s Horizon: Poems. Chapel Hill: Signal Books, 1996.

———-. Beyond Reason: Poems. San Antonio: Pecan Grove Press. 2004.

———-. “’Between Breath and No Breath’: Witnessing Class Trauma in Paula Meehan’s Dharmakaya.” An Sionnach: A Journal of Literature, Arts, and Culture. 1:2 (Fall 2005): 47-64.

———-. “Between Country and City: Paula Meehan’s Ecofeminist Poetics,” in Murmurs that Come out of the Earth: Eco-critical Readings of Irish Texts, ed. Christine Cusick. Cork, Ireland: U of Cork Press, 2010.

———-. Our Held Animal Breath: Poems. Cincinnati, OH: Wordtech Editions. 2012.

———-. Unaccountable Weather: Poems. Winston-Salem, NC: Press 53. 2011.

———-. The Fisher Queen: New & Selected Poems. Co. Clare, Ireland: Salmon Press. March 2019 (distributed in the U.S. by DuFour).

Kollontai, Alexandra. Selected Writings by Alexandra Kollontai. New York: W.W. Norton,

1980.

Mies, Marie and Vandana Shiva. Ecofeminism. New York: Zed Books, 2014.

Marx, Karl. Capital : A Critique of Political Economy London: Penguin, 1993.

Von Eschenbach, Wolfram. Parzival. London: Penguin, 1980.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman and A Vindication of Vindication of the Rights of Men. London: OUP, 2009.

Photo: Human and wolf head profiles united by woodcut pattern on the subject of unity of all living things | Shutterstock

Published on March 10, 2020.