This is part of our special feature, Me Who? The Audibility of a Social Movement.

“As for the war, that is for men…” – Hector to Andromache, The Iliad

The very notion of women in combat throws the boundaries between masculinity and femininity into question. The military is an important state institution and its gender assumptions and narratives are constantly referenced and reproduced in society as a whole. While this seems apparent for nations in combat, it also holds true for most societies in peacetime and can be ascribed to the archetypal idea that men fight wars to protect their nation, their families, and their honor, while women are supporting their efforts by caring for homes and children. There have only been two proven cases in the history of state militaries that used women in combat: The West African Dahomey Kingdom of the eighteenth century and the Soviet Union in World War II. Soviet female soldiers were efficient and feared warriors, but they were collectively discharged after the war. Thirty years later, with the enforcement of equality laws throughout the world, state militaries have started to integrate women beyond support units, but in the ca. twenty militaries that have fully integrated women, the number of women in combat positions is still low (Schølset 2013). This dynamic influences the fundamentals of a gendered society, as Egnell (2016) puts it:

If women can make significant contributions to…the most masculine and patriarchal of all worlds, there are few limits left in terms of women’s participation and empowerment in other sectors of society.

There seems to be the general assumption that by simply allowing women into the game, they are automatically part of the game. Much effort is thus dedicated on how to make positions and systems pro-forma accessible for women. But how does being in the game change women, men, and the underlying constructions of systems and organizations? Even in the military, traditional gender narratives are transformed into more complex narratives, not so much because the status of women or their role description changes, but because structures and assumptions in which they operate change.

Women in combat: beyond the binary?

A theoretical baseline for the narrative change in which women in combat operate is provided by both Anthony Giddens’ and Ulrich Beck’s concept of reflexive modernity, and Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of liquid modernity (Giddens 1990, Beck 1994, Baumann 2000). Both concepts believe that the globalized world builds on creative (de-)construction and ongoing co-construction of social practices. For deconstructive purposes, feminist scholars traditionally ask: where are the women? Here, we can draw from Judith Butler’s classical work of feminist thought concerning the performativity of gender: there is no “real” or “natural” gender; it is merely a social construction and practice independent from material bodily facts (Butler 2006). Hence, masculinity and femininity are social norms, produced only through everyday interactions of thinking, feeling, and interacting. Butler’s ideas are no longer contentious. They lie at the center of what is standard gender theory, and if we consider gender to be a construct that is performed based on social practices that are constantly examined and reformed, we have to analyze what this means in the social structures and practices of our case––the constructions of gender in military organizations.

Cohn (2013) offers a good starting point for looking at traditional symbolism of gender narratives relating to combat and the military:

War and peace are profoundly gendered on a symbolic level. War is associated with action, courage, seriousness, destruction, weapons, explosions, violence, aggression, fury, vengeance, protection, mastery, domination, independence, heroism, “doing,” hardness, toughness, emotional control, discipline, challenge, adrenalin, risk- all terms which are coded “masculine” in most cultures. Peace, in contrast, is associated with passivity, domesticity, family, tranquility, softness, negotiation, compromise, interdependence, nonviolence, a “being” rather than a “doing,” a lack of action, excitement, challenge and risk, an absence rather than a presence- all, in short, coded “feminine” in most cultures.

The common and still prevalent argument for women’s exclusion from combat is that “women are located literally and metaphorically between child-like innocence and physical incapacity,” making them “civilians by nature” (Kinsella 2011). Consider the universal moral and legal code that deems women and children illegitimate targets in war. Combine that deeply held norm with the idea that women are naturally weaker than men and thus unfit for battle. It is no wonder that their presence was thought to “spoil” unit cohesion. Cohn (2000), however, shows us the hypocrisy of these arguments, stating that they are only “seemingly objective and neutral” and in fact function as an “institutionally acceptable form of expressing many otherwise not officially sayable negative feelings about women” and asserting male superiority, while “expressing rage and grief about the loss of the military as a male sanctum.”

In modern society, the inclusion of female combatants, however, seems necessary and unavoidable, not only as a matter of law, but also as a symbolic matter of representation and diversity (Kronsell 2012).

The “respect for the rule of law” argument is straightforward. The law banning female combat has never been an internationally recognized legal concept and is now coming into conflict with national and international laws supporting gender equality (Percy 2019).

The representation argument posits that every part of society should be represented in the military. This argument, however, receives nuanced forms of critique. While Seifert (2005) argues that this is impossible because femininity and the military are incompatible, other argue that this form of representation is impossible and women who become soldiers no longer act their sex and are “desexed” (Kinsella 2011). Rather than being representative Cohn (2013) argues, women are caught between two extremes: “any form of femininity a woman enacts threatens to mark her as ‘not a real soldier;’ however, if she fails to ‘do femininity,’; she is ‘not a real woman,’ she is a ‘dyke’ or a ‘bitch.’”

In line with this thought, Kronsell (2012) claims “the goal is to be ‘one of the boys’ although not identical to a boy or man.”

While the “representation argument” refers to diversity of the outside (i.e. the civilian sphere) the “diversity argument” is concerned with the internal structures of the military. On the one hand, combat units can benefit from women’s inclusion because diversity benefits all organizations (Haring, 2013). On the other hand, women benefit combat missions not because they possess certain features “by nature” but because they were socialized to inhabit them (Bender, 2005). Importantly, Egnell (2013) shows the limits of “including for diversity”:

If women are recruited as “peace-makers,” or for their oft emphasized compassionate, diplomatic or communicative skills, they are also most likely to play “character role”…where such skills are valued…within military organizations, women will be used to fill competence gaps (and most often what is perceived as non-essential and peripheral duties) rather than being allowed to have an impact on the organization as a whole, or to compete with men on equal terms.

In the context of both military representation and military diversity, it seems masculinity is seen as the binary opponent of femininity. In practice, the sudden presence of women disrupts and challenges inherent hegemonic masculine norms of the military and therefore the entire military apparatus. And while the military as a state institution is not immune to the effects of re-constructions of the world order and should hence also be open to reflexive re-self-conceptualization, the gender question seems to be noticeably different. It puts the organization under pressure to either revise or valorize its own self-conception, internal structure, and culture. The organizational re-constructiveness blurs the lines between the military as an institution and the soldier––creating inherent ambiguities in the self-conception. This is also connected to the wider question of military competences: is “fighting power” the main scale on which to evaluate a military’s strength? And is this power defined in accordance with the actual operational needs? The assumption that existing military culture and structure are perfectly adapted to the needs of modern militaries can limit the organization’s capacities and has profound impacts on the integration of women. Their inclusion is, from an institutional point of view, limited to “avoiding damage while maintaining the existing order” (Egnell 2014).

Cooking, children – combat? Women and the bundeswehr

Until very recently, the German armed forces (Bundeswehr) was an institution that tried avoiding such damage at all costs. It had a strong social and legal rule against female combat, a rule never lifted due to internal change, but due to external pressure.

After 1945, both the German public and military actively distanced themselves from martial ideals and heroism. The Bundeswehr of 1955 was built by the Allied powers to explicitly exclude any warrior stereotypes that existed under the Nazi regime. Instead, its soldiers were to ground their identity in democratic values and loyalty to EU and NATO. At the time the new German constitution included compulsory military service for men while excluding women from armed service, legislatively enshrining the “norm against female combat.” This was based on a culturally internalized social norm against female combat, dating back to the World Wars: a women’s role, in war and peace, was to be a mother for her family and the nation (Campbell 1993:313; Hagemann/Schüler-Springorum 2002). After World War II, the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) reinforced this narrative and firmly placed the woman in the sphere of “Küche, Kinder, Kirche” – cooking, children, church. In 1975, the Bundeswehr opened medical and in 1991 music corps for women, where they served as stereotypically gendered non-soldiers. Only in 2000, the legal rule against women serving in combatant functions was lifted after a ruling of the Court of Justice of the European Union considered it discriminatory. Within months, the law and the constitution were changed, granting women unrestricted access to all roles within the military, yet without challenging the social norm against female combat.

The case of gender narratives in the Bundeswehr is valuable for understanding gender in the military more broadly since it highlights how non-linear gender constructions are, even in the military. The narratives can be analyzed through its communication campaigns. They are bridging internal truths and external publicity campaigns. I show this along four timelines: one dating to the time before the judgement in 2000, and then progressively from 2010-2013; 2013-2015 and 2015-2018.

Before 2000

Before 1999, there was little public engagement with gender narratives in the military or militarized masculinity. Conscription was culturally accepted as a mechanism to make boys “grow up.” Military masculinity was only discussed in the context of the peace movement, which lobbied for the abolition of the whole institution. The compulsory military service saved the armed forces from recruiting personnel overly active. Most material published before the suspension of conscription focuses on the purpose of the military rather than more sophisticated narratives of soldier identities.

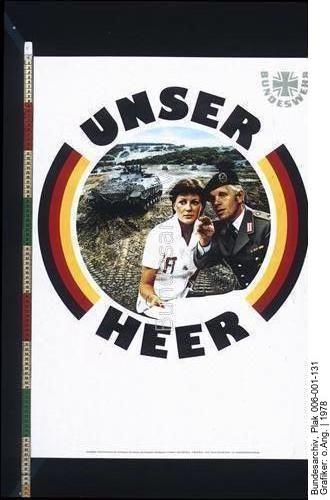

Figure 1: Recruitment Poster 1990. Text: “Soldiers are ensuring operational readiness of an air defence site”. ©Bundesarchiv

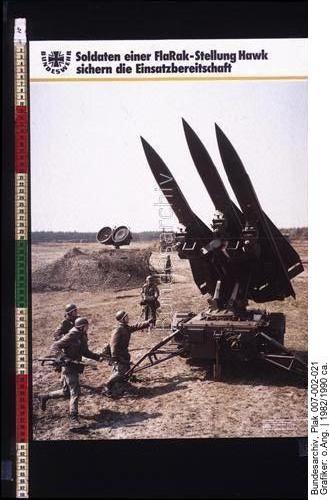

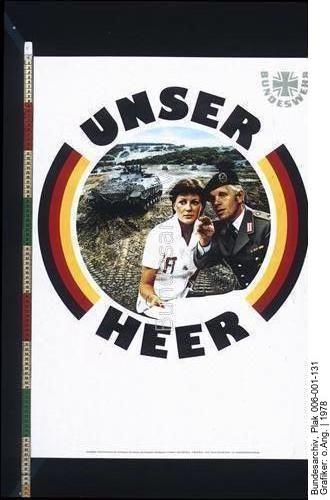

If images of women appear at all, they are portrayed as attentive, subservient, either in clearly feminine roles or being saved by men.

Figure 2: Image Poster 1978. Text: “Our Army”. ©Bundesarchiv

2010-2013

Between 2010 and 2013, three important caesuras influenced the Bundeswehr’s gender narratives. First, in 2010, the Bundeswehr suffered the first soldiers killed in battle since its founding, marking the turning point for its conceptualization as a peacekeeping organization and making the role description and requirements more robust. Second, the German government suspended conscription in 2011, marking a new era in the Bundeswehr’s constitution. The third caesura was the appointment of Ursula von der Leyen as the first female Minister of Defense and chief of the armed forces in 2013.

To define the transformation from conscription to voluntary service, the Bundeswehr launched the campaign “We. Serve. Germany.” (Wir. Dienen. Deutschland.), aiming to condense its tradition and self-conception. Yet the gender narratives are anything but transformational: On the left, a woman in uniform squads down about to embrace two young girls. On the right, a man in full combat gear holding an assault rifle observes a scenery with multiple armored patrol vehicles. While the female soldier is a faceless mother waiting to embrace her daughters, the man embraces his rifle closely. The observer’s relationship with the female soldier is protective: she exposes her back, is unarmed, and solely focused on the children. The observer’s relationship with the male soldier is contrary: he displays a protective posture and is in command of the situation. The images are transporting gender narratives of the strong, masculine combatant and the motherly woman.

Figure 3: Pictures form image leaflet “Wir. Dienen. Deutschland.“ 2011. ©Bundeswehr

2013- 2015

Soon after von der Leyen took office, she actively worked on increasing the attractiveness of the military as an employer on the inside and out, framing it as a modern organization with good career prospects and benefits.

Figure 4: Recruitment campaign 2013/ 2014. Text: “Doctor’s assistant; paratrooper; administrative specialist”. ©Bundeswehr

At that time, a recruitment campaign was launched that specifically targeted women and shows the conflict that arises with the attempt to integrate women into the battlefield without challenging assumptions of gender: The job description has to be “normalized” and “civilized” so that women can take it on. The image seemingly aims to show the variety of career choices for women in the Bundeswehr, from civilian assistant to specialized combatant. By displaying it as one of many jobs, being a combatant is normalized – even for women. The job is flexible, it does not have any special requirements and is as “clean” as the women and her surroundings. Following public criticism because of its sexist nature (e.g. Spiegel Online 2014), the Bundeswehr issued a statement explaining the campaign was designed by female soldiers. The intended messages were “every female soldier is a woman first”. The head of the MoD HR department is quoted: “Women have special qualities and strengths that we, the Bundeswehr, want to profit from more” (Bundeswehr 2013; Reimann 2014). The campaign has no reference to the specific work of a soldier or the concepts of combat but suggests what a “real” woman should look like (pretty!), implying that women’s “special qualities” are of a different kind. Although the campaign portrays becoming a combatant as an accessible option, it characterizes women as interested in a career that fits the “feminine” lifestyle, negating what the job of a soldier or even a combatant entail. Although at that point the Bundeswehr tried to acknowledge the reality of female soldiers and their work, it is striking how inherently non-disrupted traditional gender stereotypes were at the time of this campaign.

2015- 2018

In 2015, the Bundeswehr launched a campaign focused on the unique features of soldiering instead of portraying it as a job like any other. They expanded their social media presence, allegedly opening up the “black box military,” with formats showing various military professions, their everyday work, exercises and missions abroad.

Figure 5: Top: Picture from image leaflet “Im Visier” 2017; Bottom: Recruitment campaign 2018. Text: “#secure”. ©Bundeswehr

The gender narratives here are much more varied than in previous campaigns. The male soldier is seen embracing a child without being emasculated or shunned from the group, whilst the female soldier appears in full command of the situation and integrated into a functional work unit. The role the respective gender takes on is reversed. The submissive element is taken out of the parenting image while the woman’s pose is supported by the slogan #secure.

Figure 6: Recruitment campaign 2018. Text (top to bottom): “Do what really matters”; “#Leading”; “Follow your calling”. ©Bundeswehr

The most powerful image shows a female leader––she still looks feminine, yet with no obvious sexualization. Behind her is a docked submarine at sunset. The picture is significant in several ways: Submarines have historically been one of Germany’s more prestigious military branches, and it is one of the technical military fields in which Germany is an international leader. Submarines have traditionally been closed for women in most militaries; and the picture shows a female soldier with the slogan #leading and “follow your calling,” suggesting that her calling is to be a leader. This creates the narrative of a female soldier who is a woman and a military leader, not in any, but in a highly prestigious, formerly exclusively male combat branch.

These images show the gradually changing gender narratives depicted in the Bundeswehr’s official communications, replacing the traditional binary by more liquid, perceivable yet non-static, gender narratives.

The soldier of the future: liquidizing the binary

Although feminist and constructivist literature overwhelmingly reject gender binaries, the military thus far has not. The modern world challenges the structures and standards of operation of the military on all fronts, but they can only be met by the military if it continues to liquidize its gender narratives and attempts to integrate various identities instead of assimilating them into pre-existing binaries. The archetype of the traditionally masculine warrior is being challenged on all fronts. Criticism about sexist behavior and sexist rituals in the military turn “manly banter” into criminal offences. All the while women are taking up more space in the discourse about war and peace as speakers and subjects, changing policies. Digitization and new weapon systems change the face of war from face-to-face physical combat to remote and hybrid forms. If the gender narratives change, they open up binary assumptions to more complex constructions which are not necessarily “de-gendered” or “re-gendered” but possibly and as a first step, as in the case of the German military just ‘less’ gendered.

“Women in war disrupt the order of things,” says Kinsella (2011) and yet it seems that the order of things is as much under constant re-construction, as the very concept of war and the concepts “male” and “female.”

Elisabeth Pauline Gniosdorsch holds an MSc in Conflict Studies from the London School of Economics and Political Science, where she conducted the research this article is based on. Before that, she studied Political Science at Freie Universität Berlin and the American University in Cairo. Her interests lie in defense and security policy, which she feels are in desperate need of progressive, non-masculine perspectives. She currently works as a management consultant for the German Armed Forces.

References

Acker, Joan. 1990. Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations. Gender & Society. 4. 139-158.

Ahrens, Jens-Rainer, Bender, Christiane, and Apelt, Maja. 2005. Frauen im Militär: Empirische Befunde und Perspektiven zur Integration von Frauen in die Streitkräfte. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Apelt, Maja. 2019. “Militär und Krieg: der kämpfende Mann, die friedfertige Frau und ihre Folgen”. (Military and War: The Fighting Man, the Peaceful Woman and their Impact). Kortendiek, Beate, Riegraf, Birgit, and Sabisch, Katja. Handbuch Interdisziplinäre Geschlechterforschung. Springer Fachmedien.

Apelt, Maja, and Scholz Sylka. 2014. „Männer, Männlichkeit und Organisation“ (Men, Masculinity, and Organisation). In: Funder, Maria (ed.). Gender Cage – Revisited: Handbuch zur Organisations- und Geschlechterforschung. 1 ed. Nomos.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Polity Press.

Beck, Ulrich. 1994. Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Polity Press.

Bender, Christiane. 2005. „Geschlechterstereotypen und Militär im Wandel. Symbolische und institutionelle Aspekte der Integration von Frauen in die Bundeswehr“ (Changes in Gender Stereotypes and Military. Symbolic and Institutional Aspects of the Integration of Women into the Bundeswehr). In: Ahrens, Jens-Rainer, Bender, Christian, and Apelt, Maja. (eds.). Frauen im Militär: Empirische Befunde und Perspektiven zur Integration von Frauen in die Streitkräfte. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Campbell, D’Ann. 1993. Women in Combat: The World War II Experience in the United States, Great Britain, Germany, and the Soviet Union. The Journal of Military History, 57, 301-323.

Bundeswehr. 2013. Anzeigen-Kampagne: Frauen werben für Frauen. Originally retrieved from: http://www.frauen-in-der-bundeswehr.de (Accessed on 15.08.2019).

Butler, Judith. 2006. Gender Trouble. Routledge.

Cohn, Carol. 2000. “How Can She Claim Equal Rights When She Doesn’t Have to Do as Many Push-Ups as I Do?”: The Framing of Men’s Opposition to Women’s Equality in the Military. Men and Masculinities, 3, 131-151.

Cohn, Carol. 2013. Women and Wars. Polity.

Connell, Raewyn. 2005. Masculinities. Polity.

Egnell, Robert. 2013. Gender Perspectives and Fighting. Parameters, 43, 33-41.

Egnell, Robert. 2014. Gender, Military Effectiveness, and Organizational Change: the Swedish Model. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Palgrave Macmillan.

Egnell, Robert. 2016. Gender Perspectives and Military Effectiveness: Implementing UNSCR 1325 and the National Action Plan on Women, Peace, and Security. Prism : a Journal of the Center for Complex Operations, 6, 72-89.

Giddens, Anthony. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Polity in association with Blackwell.

Goldstein, Joshua. 2004. War and Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hagemann, Karen, and Schüler-Springorum, Stefanie. 2002. Home/front the Military, War, and Gender in Twentieth-Century Germany. Berg.

Haring, Ellen. 2013. What Women Bring to the Fight. Parameters, 43, 27-32.

Kanter, Rosabeth Moss. 1977. Men and Women of the Corporation. Basic Books.

Kinsella, Helen M. 2011. The Image before the Weapon: a Critical History of the Distinction between Combatant and Civilian. Cornell University Press.

Kronsell, Annica. 2012. Gender, Sex and the Postnational Defense Militarism and Peacekeeping. Oxford University Press.

Kümmel, Gerhard. 2002. Complete Access: Women in the Bundeswehr and Male Ambivalence. Armed forces & society, 28, 555-573.

Kümmel, Gerhard. 2008. „Truppenbild mit Dame. Eine sozialwissenschaftliche Begleituntersuchung zur Integration von Frauen in die Bundeswehr.“ (Troop Picture with Lady. A Sociological Study on the Integration of Women into the Bundeswehr). Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut der Bundeswehr.

Kümmel, Gerhard. 2014. „Truppenbild ohne Dame. Eine sozialwissenschaftliche Begleituntersuchung zum aktuellen Stand der Integration von Frauen in die Bundeswehr“ (Troop Picture without Lady. A Sociological Study on the Integration of Women into the Bundeswehr). Sozialwissenschaftliches Institut der Bundeswehr.

Mathers, Jennifer. 2013. Woman and State Military Forces. In: Cohn, Carol (ed.) Women and Wars. Polity.

Percy, Sarah. 2019. What Makes a Norm Robust: The Norm Against Female Combat. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4, 123-138.

Schjølset, Anita. 2013. Data on Women’s Participation in NATO Forces and Operations. International Interactions, 39, 575-587.

Seifert, Ruth. 2005. Weibliche Soldaten: Die Grenzen des Geschlechts und die Grenzen der Nation [Female Soldiers: Limits of Gender and the Limits of Nation]. In: Ahrens, Jens-Rainer, Bender, Christiane, and Apelt, Maja (eds.) Frauen im Militär: Empirische Befunde und Perspektiven zur Integration von Frauen in die Streitkräfte. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Reiman, Anna. 2014. Bundeswehr blamiert sich mit Frauen-Kampagne [Bundeswehr Blunders with Women’s Campaign]. Spiegel Online. 02.10.2014 Retrieved from: https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/bundeswehr-werbekampagne-fuer-frauen-blamiert-von-der-leyen-a-994997.html (Accessed on 03.03.2020).

Images

1- Bundesministerium der Verteidigung. 1990. Soldaten einer FlaRAk-Stellung Hawk sichern die Einsatzbereitschaft. Bundesarchiv [Federal Archive]. Retrieved from: https://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/archives/barchpic/view/2195830 (Accessed on 15.08.2019).

2- Bundesministerium der Verteidigung. 1978. Unser Heer. Severin Schmidt GmbH + Co., Graphische Werke Flensburg. Bundesarchiv [Federal Archive]. Retrieved from: https://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/archives/barchpic/view/7255106 (Accessed on 15.08.2019).

3- Bundesministerium der Verteidigung. 2011. Untitled. Wir. Dienen. Deutschland. Das Selbstverständnis der Bundeswehr. pp. 4, 6. (Accessed on 03.03.2020)

4- Bundesministerium der Verteidigung. 2013. Untitled. Originally retrieved from: http://www.frauen-in-der-bundeswehr.de/ (Accessed on 15.08.2019).

5.1- Bundesministerium der Verteidigung. 2017. Untitled. Arbeitgeber Bundeswehr Im Visier. Ausgabe (Vol.) 5. Summer 2017 (Accessed on 03.03.2020).

5.2- Bundeswehr. 2018. No Title. Bundeswehr Karriere Retrieved from: https://www.bundeswehrkarriere.de (Accessed on 03.03.2020).

6- Bundeswehr. 2018. No Title. Bundeswehr Karriere. Facebook 19.10.2018 (Accessed on 03.03.2020).

Published on March 10, 2020