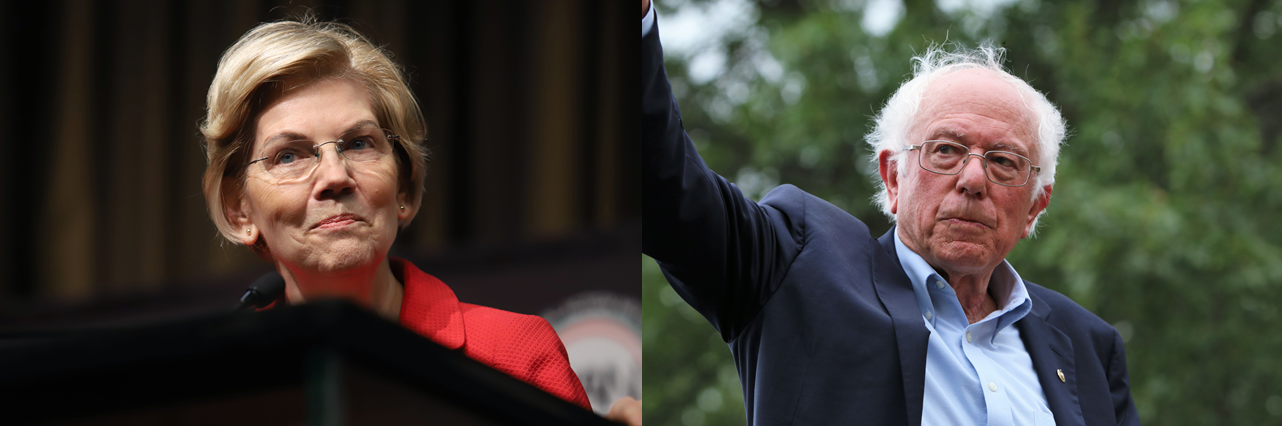

Presidential candidates in the current Democratic primary campaign are proposing major structural changes to America’s political economy in a way not seen since perhaps Ronald Reagan’s 1980 run for President, when he called for the liberalization of America’s labor market, deregulation of industries across the board, and welfare reform. While perhaps less discussed than both candidates’ proposals for the healthcare sector and wealth taxation, Sanders and Warren are part of a broader coalition of legislators calling for the US to adopt elements of Germany’s system of Mitbestimmung, or co-determination. Building on Senate bills that they are co-sponsoring, Senators Sanders and Warren want to tackle rising wealth inequality in the US by giving American workers a newfound role in the ownership and management of their firms. A number of trade unions and progressive organizations have endorsed these and similar proposals, and they have attracted critique and commentary by journalists and analysts from across the political spectrum.

Both Sanders and Warren have framed these proposals in a way that leverages respect for the German economy’s presumed efficiency and productivity. Sanders notes that his program would be “similar to what happens under ‘employee co-determination’ in Germany, which long has had one of the most productive and successful economies in the world.”[1] Warren’s press release concerning the ACA frames the bill as an effort to, “[Borrow] from the successful approach in Germany and other developed economies.”[2] Sanders’ platform calls for 45 percent worker representation on the boards of listed companies and private firms with annual revenues in excess of 100 million dollars. Warren’s platform follows the policy, which she has laid out in S. 3348, which calls for 40 percent worker representation on the boards of companies with tax receipts in excess of 1 billion dollars. Each of these proposals is more aggressive than the Reward Work Act, the most widely supported co-determination bill currently in Congress, which both Sanders and Warren support have sponsored. The Reward Work Act calls for 1/3 worker representation on the boards of listed companies, but even this proposal would mark a sea change in US industrial relations. In terms of board parity and the breadth of application, these initiatives are comparable to the range of German statutes which provide for between 1/3 and ½ worker representation at firms depending on their size.

But does this formal similarity mean that co-determination would benefit American workers in the way that it has German ones? And more to the point, what is it exactly that American progressives hope to reap from German-style co-determination? By calling attention to the higher wages and representation that co-determination offers German workers, Sanders and Warren have revived an American tradition of transatlantic dialogue and policy exchange, just as they have prompted a revival of American socialism and progressivism.[3] Yet, paradoxically, the effervescent American discussion around co-determination and German political economy comes at a time when the “German model” itself is increasingly being called into doubt and criticized. Debate has, thus far, largely left the historical and social context of co-determination in Germany unexamined, as well as the ways in which co-determination has been watered down and fragmented in recent years.[4]

What should we make of progressive American interest in such Rhenish practices at a time when Mitbestimmung and other hallmarks of the European Social Model are under relentless pressure to “reform?” More generally, how should we evaluate the differences in political and social conditions between the United States and Germany at present, as well as in the immediate post-war period when such industrial relations systems were established?

How the German System Works and How it was Won

“Co-determination” is often used as short-hand for the body of post-war legislation that mandates that a portion of a company’s supervisory board must be elected by the company’s workers—the dynamic which American progressives are seeking to emulate. However, co-determination or Mitbestimmung more accurately refers to the very principle that workers be involved in and consulted in the management of the firm that employs them—board representation is just one institutionalized form of this more general principle. Just as important and in many ways prior to company-level co-determination is establishment of shop-level co-determination in the form of the works council. The works council or Betriebstrat is elected by workers at a given place of work and is empowered to enforce collective agreements, pursue grievances, and oversee production changes that affect employee working conditions. Works councils also serve as a training ground for workers to learn through practice how to variously confront and collaborate with management. In addition, elected works councils frequently serve as the nominating bodies for candidates to serve on the company’s board. Finally, the trade union movement plays a role in every level of co-determination. Typically, trade union confederations and bussiness associations negotiate major compensation guidelines on the sectoral level. Works council members are frequently affiliated with one or another union, and trade unions serve as links and resources to otherwise isolated works councils.

In principle, there is no reason why Congress could not legislate some form of co-determination in the United States.[5] Rather, the real question is: what would worker representation on corporate boards look like in the United States, where there are no works councils, and where most firms are non-union and lack collective bargaining structures? To the extent that corporate co-determination in Germany and elsewhere is effective at giving workers a consequential “seat at the table,” it is because worker representation in the boardroom is undergirded by a rich ecosystem of works councils that populate the many workplaces and divisions of a given company, and buttressed by a trade union movement which connects workers and works councils across many hundreds and thousands of firms.

The features of the German system have developed in a dialectical fashion through the struggle and compromise between German capital and labor since the late nineteenth century. When the 1891 Worker Protection Act introduced a system of voluntary consultative councils the Social Democratic leader August Bebel dismissed it as a “sham system.”[6] Up through the First World War, the Social Democrats and trade unions pushed for mandatory works councils with real power in their firms. After the end of the Great War and the subsequent eruption of workers’ and soldiers’ soviets across Germany, the 1920 Works Council Act was passed with the goal of institutionalizing and normalizing those revolutionary councils. As Weimar sociologist Emil Frankel put it, a majority of German workers may not have wanted a Bolshevik style council revolution, but they “nevertheless wanted an economic council system which would strengthen their position within the establishment and permit them to have a decisive voice in the whole process of production.”[7] After being suppressed and deformed under the Third Reich, revived trade unions and ad-hoc works councils approached Allied occupation forces to begin rebuilding a system of co-determination for the new Federal Republic. As legal historian Ewan McGaughy has demonstrated, the progressive development of the co-determination system from 1949 onward was only possible because of the relative strength and unity of the trade union movement.[8] Finally, even after the crest of West Germany’s Wirtschaftswunder, the trade union movement and left-wing forces within both the SPD and CDU fought for and won an expansion of corporate co-determination with the Mitbestimmungsgesetz of 1976 at a time when the FDP and business community were pushing to roll back the system.

If corporate co-determination in the United States is meant to deliver higher wages, profit sharing, and a real level of self-management and self-ownership for American workers, it must be understood that in Germany it is not corporate co-determination alone that delivers these things. Rather, it is strong and dynamic trade unions and works councils that have delivered and sustained the co-determination system. This is not to say that the United States or any place needs to have German style works councils, but that whatever the forms of co-determination instituted by statute, they will only be potent and effective if the United States sees a resurgence of working-class politics and organizing at every level.

The Causes of the German Model’s Contemporary Challenges

The German system’s evolution under globalization and liberalization over the last thirty or more years, the subsequent decline in the strength and comprehensiveness of the codetermination system domestically, and the mixed results of its export abroad all make clear the centrality of independent working-class politics to the effectiveness of co-determination. The declining power and inclusiveness of Germany’s trade unions is demonstrated by the fact that while in 1996 70 percent of German workers were covered by sectoral wage agreements, by 2017 only 47 percent enjoyed such protections.[9] Since the 1980s, under the pretense of worker empowerment and the imperative of “flexibility”, works councils gained the ability to agree to supplemental open-clauses with management in abrogation of larger sectoral agreements. This almost always results in less-beneficial agreements pushed by management at the shop level. Political efforts to diminish the presence of trade unions in the co-determination process, and to exclude them entirely from certain new industries, have further fragmented the co-determination system. Likewise, the development of supply chains and offshoring has limited the power of co-determination domestically, and has made co-determination less universal as workers in foreign subsidiaries are excluded from board-level representation, and only in some cases do they have access to the works council system. Even in the EU where there have been steps to bridge this gap, German trade unions are still faced with the pressure to move production East where German employers can take advantage of cheap, disempowered labor. In the best of cases, trade unions in particular sectors have managed to protect certain existing jobs and hard-won benefits, but have rarely prevented offshoring to cheaper labor markets.[10]

Nor has German co-determination been proven exportable per se. Optimistic projections that German multinationals might serve as conduits of Germany’s enviable prosperity and industrial peace have been proven wrong again and again. German multinational firms in China balance imperatives to take advantage of a local labor force that is prohibited from organizing while maintaining the allure of German companies as “cutting-edge” and “good” employers.[11] In Hungary, where, like much of Eastern Europe, post-communist governments passed labor and industrial relations statutes on the German model, the general weakness of the labor movement and the exclusion of trade unions by management often undercuts the potential power of works councils and worker representatives.[12] Absent strong self-organization by workers in the form of trade unions or otherwise, works councils and board representation can be rendered nominal or even coopted by management – tools of legitimation not dissimilar to the disciplinary role of “official” trade unions that existed under socialism. A final instructive episode which illustrates the limits of the German model both in Germany and outside is the inability of the Global Works Council of Volkswagen and its board representatives to protect the organizing rights of VW workers and works council members at VW’s Tennessee assembly plant, despite its representation on the auto group’s supervisory board.[13]

Progressives in the US must understand that if co-determination is a desirable model on which to reform American capitalism, they must also work to foster a strong and viable labor movement to give life to these institutions. The RWA and ACA make no specific provisions for the election of worker-board-members, but defer to the National Labor Relations Board. While in Germany and elsewhere worker members of the board often come up through works council and union activities, it’s unclear what such a nomination and election process would look like at an American company such as Walmart or Amazon where workers lack organizations and are meticulously atomized by management. The top-down introduction of board-level co-determination could result not in a newfound degree of clout for American workers, but in a new plebiscitary form by which American managers can manufacture consent in the workplace and virtue-signal to the general public. With a strong and dynamic enough labor movement, however, one can imagine American workers responding by demanding more substantive representation in the workplace, much like the Social Democrats of the early twentieth century. To this end, like German statutes, American laws ought to lay out a process for nomination and election of worker board members that is as democratic and worker-run as possible. With recent strike victories across both the service and manufacturing sectors, and with more Americans approving of unions than at any time since the 1970s, the time is ripe to pair co-determination legislation with other laws aimed at the broader regeneration of the labor movement and independently organized working class power.

Kyle Shybunko is a PhD candidate in the History Department at New York University. His dissertation, “Foreign Foundations and Hungary’s Transition from Communism to Neoliberalism, 1982-1994,” investigates the role of West German and American foundations and democracy promoters in fostering particular models of civil society and visions of democratic capitalism in Hungary. Currently a Doctoral Fellow at the Remarque Institute, he has been a Visiting Fellow at the Karl Polanyi Institute for Global Social Studies at Corvinus University and a Visegrád Fellow at the Open Society Archive in Budapest.

References:

[1] https://berniesanders.com/issues/corporate-accountability-and-democracy/ – Steven Hill of the Hans Böckler Stiftung notes that “Germany’s example already has been a huge help in raising the credibility of this proposal,” https://www.steven-hill.com/co-determination-takes-the-spotlight-in-the-us/.

[2] https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Accountable%20Capitalism%20Act%20One-Pager.pdf

[3] Kiran Klaus Patel, The New Deal: A Global History (2017); Mary Nolan, The Transatlantic Century (2012); Daniel T. Rogers, Atlantic Crossings (1998).

[4] For a range of commentaries on the proposals: “Elizabeth Warren has a plan to save capitalism,” by Matthew Yglesias, Vox, August 15, 2018; “Elizabeth Warren Plans to Destroy Capitalism by Pretending to ‘Save’ It,” by Scott Schackford, Reason Magazine, August 15, 2018. “Bringing the Workers on Board: The Catholic Roots of Co-determination“ by Matthew Mazewski in Commonweal, March 19, 2019.; “Worker Representation on Boards Won’t Work Without Trust” by Raffaella Sadun, August 17, 2018 in Harvard Business Review.

[5] Ewan McGaughey, “Democracy in America at Work: The history of Labor’s Vote in Corporate Governance,” Seattle University Law Review, Vol. 42, 2019. McGaughey argues that the passage of co-determination laws at the Federal level might be difficult, but not uniquely so, and that passage at the state level is eminently practicable.

[6] As quoted by Ewan McGaughey in “The Codetermination Bargains: The History of German Corporate and Labour Law,” LSE Law, Society and Economy Working Paper 10/2015, page 19. This paper offers a superb account of the evolution of co-determination in German law over the course of the long 20th century.

[7] Emil Frankel, “The German Works Councils,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 31., No. 5 (Oct., 1923), 714-715.

[8] McGaughey 2015, 35-38.

[9] Wirschafts- und Sozial-wissenschaftliches Institut. Tarifbindung und betriebliche Interesenvertretung: Ergebnisse aus dem IAB-Betriebspanel 2013, 287. Collective Bargaining Report 2018, 16.

[10] Bramucci, Allessandro; Zanfei, Antonello (2014) : The governance of offshoring and its effects at home: The role of codetermination in the international organization of German firms, Working Paper, No. 40/2014, Hochschule für Wirtschaft und Recht Berlin, Institute for International Political Economy (IPE), Berlin.

[11] Boy Lüthje, “Exporting corporatism? German and Japanese Transnationals’ Regimes of Production in China,” in Chinese Workers in Comparative Perspective, ILR Press, 2015. “…the prospect of the German model of labor relations becoming another successful export in China remains limited…the missing key is in the almost complete lack of collective bargaining relations and the weakness of the respective collective actors.” [36].

[12] For the weakness of trade unions and of labor law in Hungary, see for example Irene Schipper “Electronic assembly in Hungary: how labour law fails to protect workers,” in Flexible Workforces and Low Profit Margins: Electornics Assembly Between Europe and China, ed. Jan Drahokoupul et al. ETUI, 2016.

[13] https://www.labornotes.org/blogs/2019/06/volkswagen-declares-war-against-works-council-and-german-union

Published on February 24, 2020.