This article is funded by the European Studies Undergraduate Paper Prize, awarded by the Council for European Studies.

Introduction

The wake of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1989 featured a dramatic decline in the participation rate of women in government.[1] Research attempting to rationalize this demographic shift has often omitted the sociocultural factors that influence social practice and normative values, specifically within discourses on behavioral changes in the absence of a communist, faux-egalitarian society. Scholars are able to assess how meanings and values are constructed and how they may account for a shift in cultural attitudes towards women, potentially yielding behavioral effects among viewers when considering the role of popular media as a cultural signifier, and subsequently mapping representations of femininity during the Soviet and post-Soviet era of animation.

An investigation of the discourses on femininity and womanhood in Soviet animation seeks to advance the claim that representations of gender roles or connotations of femininity shifted following the dissolution of the Soviet Union and thus contributed to a behavioral norm which discouraged women’s participation in governance and upheld patriarchal gender hierarchies in sociopolitical contexts. During this time, the government-owned company that monopolized the production and distribution of all popular animated content was conjunctively dissolved.[2] The hegemonic principle of conformity is a unique layer in the discourse on femininity that largely disappears after 1989, and is in some ways replaced by more prominent caricatures of masculinity and femininity, as if to compensate.[3] The result is a new representation of state-sponsored behavior. Ultimately, I have sought to identify how gender and femininity were represented in popular Soviet animation from 1950 to 2005. These findings help conceptualize how subliminal messaging regarding sanctioned behavior, featuring submissiveness, modesty, and conformity recodes and maintains hierarchies of power during sociopolitical and economic turbulence.

In order to investigate this, I have reviewed literature regarding representations of femininity and womanhood in Soviet animated adaptations of European folklore. This encompasses the studies of folkloric specialists who engage with the nuances of symbols and rhetoric within animation. This review provides a suggested methodological approach in conjunction with linguistic expertise in Russian colloquialisms.

Theoretical Frameworks

The primary schools of thought that emerge throughout the following scholarship regard the use of media as a cultural signifier and apply two distinct lenses of analysis to their data. Dominant patterns regarding economic status, color theory, and compliance are investigated in existing scholarship. There are auxiliary models of critical rhetoric application and critical social theory that contribute to framing the findings presented by the noted researchers- each advance my own investigation of the meanings and ideas evoked by specific representations of women in animated folklore.

Media theory accounts for the relationship between animation and the derived representations within the texts. Contextualizing the discourse on femininity is contingent upon understanding how the animation serves as an indicator of the values and priorities of a society. Media as a cultural influence is explored via cultivation theory, which dictates that media is pervasive and propagates a “general view of reality over time.”[4] Researchers and theorists classify Gerbner’s cultivation theory as reliant on a model of linearity- if media has an influence on its audience, then those with greater media exposure will overwhelmingly express behaviors or ideas that reflect those being portrayed when compared to non-consumers.[5] The acceptance of cultivation theory as a model of explanation regarding a population’s relationship to media is rooted in observations regarding how popular culture creates a cognitive consensus regarding content.[6] In this context, cultivation theory indicates that the values and priorities perpetuated in media can matriculate into the fabric of cultural understanding.[7] The application of cultivation theory to my research provides a conceptual framework in which the relationship between representation in media and an audience can be explored, justifying research on the use of mass media as a mechanism for influencing societal attitudes. This frames the multiple layers to the discourse on femininity expressed within my texts, specifically discourses on conformity to social practice and gender dynamics.

The critical socialist perspective posits that representations of women in animated folklore were consistently evolving, even prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Essentially, this school of thought considered the critical reception of media by its audience to be indicative that various perspectives of socialism, and ergo various perspectives on femininity, rendered it difficult for the media to shape the values of the post-Soviet community.[8] Consumers of media are awarded agency within this school of thought, negating the alleged production of a false consciousness imbricated with a socialist agenda.[9] The submission of women was valued, but only as a byproduct of misconceptions of “socialist patriotism.”[10] That is, submission is not interpreted to exclusively be valued among women, but rather a part of the greater preference of communal submission associated with socialist doctrine. This school of thought emphasizes the versatility with which women were portrayed, delineated by the facets of the aforementioned submissive behavior, supported in part by assessing the frequency of derogatory colloquialisms as a means of subversive subjugation.[11]

The critical socialist perspective argues that the relevant texts that serve as indicators of societal attitudes towards women are not the animated series themselves, but their critical reception. Researchers like MacFadyen found a lack of consistency among the representations of women across multiple animated platforms following the World War II.[12]MacFadyen explains that the female or feminine characters do not play a significant enough role in the texts to be considered as integral to the messages presented— in a sense, discourses on femininity and womanhood are largely overlooked in the interest of assessing representations of socialist ideology. Methodologically, this school of thought analyzes discourses on women and their behavior as a layer within the discourse on socialism, developing an array of interpretations regarding the valued behaviors of women and place them on a spectrum from submissive to manipulative.[13] The critical socialist perspective advances the claim that this microcosmic discourse on women evolved along with the historical relationship with socialism as a socioeconomic and political prerogative. These findings have compelled me to reverse the critical socialist methodology to bring the focus to the limited screen time of women, analyzing socialism as a layer within the discourse on femininity. This has informed my understanding of the role of conceptions of conformity and how they perpetuate gender roles via representations of preferential behavior of women in animation. I have chosen to view socialism as a facet of the discourse on femininity, as opposed to the other way around, in order to ensure that the meanings and ideas elicited by the text are not obscured by the general assumption that time period and content would immediately render it socialist propaganda and nothing more. This school of thought falters in comprehensively analyzing caricatures of masculinity and femininity, instead concluding that representations are a manifested byproduct of the intention of the production company, too much is left to assumption of intent.

The feminist theoretical approach indicates that the discourse on femininity was largely monolithic, attributed in part to the government subsidized Soyuzmultfilm production company. The representation of protagonist women as sexless and submissive is consistent throughout the evolution of the animated content, characterized by the use of color as an indicator of power and musical melodies and lyrics as a signifier of the bucolic and inferior.[14] From a methodological standpoint, this discipline utilizes a folkloric model of analysis in classifying visual imagery or rhetoric within a hierarchal structure of power- it establishes representation in media as a cultural signifier and component of national memory and female identity.[15] This approach maps the dynamics of power within the relationships of male and female characters as opposed to placing value in individual symbols, considering the representation of woman as inferior through their portrayed passivity to be universal and thus constant throughout the contextual framework of analysis.[16]This is seen most prominently in Kononenko’s work, throughout which she finds that women depicted in animated folklore wear clothing similar in color and shape, are admonished for speaking out of turn, and are revered for their devotion to fathers or husbands.[17] However, Kononenko joins other scholars within this school of thought in failing to delineate different representations of women playing different roles— more specifically, there is little to no exploration of the representations of villainous women in folklore. This omission has prompted my reconfiguration of the traditional folkloric model of analysis such that it includes the multiplicity of representation alongside a previously established codification of rhetoric used by and towards women in order to evaluate the nature of an interaction as either positive or negative employed by critical feminist theorists.[18] In using language as a signifier of power and thus an indicator of hierarchal structure, both in regard to gender and economic status, this model, despite its omissions, poses as a valuable method of analysis when applied to discourses on femininity that precisely address language and rhetoric.

Thus within this school of thought, there is a subset of scholarship that emphasizes rhetorical analysis, for which I have employed Gramsci and McKerrow’s explorations of cultural hegemony to interpret the role of language in constructing societies.[19] Gramsci’s conceptions of telos in political rhetoric provide context for how questions of usurping a dominant discourse, in this case the pivot in women’s roles in a newly independent post-Soviet state, have been framed.[20] I have used this understanding of changes in discourse in conjunction with the findings of cultivation theory in order to support my claim that the representations of femininity in animated folklore have created a tangible impact on societal attitudes towards women and, more broadly, gender roles. A literature review of the three schools of thought brings out a number of important elements which will require my careful attention to while uncovering layers of discourse that further expand upon conceptualizations of femininity and womanhood in Soviet animation.

Methodology

This methodology is grounded in the categorical components of the canonical folkloric model of analysis for the purpose of determining the relationality of representations of gender (aforementioned value judgements of positivity or negativity). Based on the codification system employed by scholars within the feminist theoretical approach, this system analyzes relationships between color, language, and systems of power and dominance by synthesizing attitudes towards expression of femininity and meanings educed by visual representations and colloquial language.

This method of analysis has been expanded to further categorize feminine characters by their role in the plot—i.e., whether they are the hero, the villain, or superfluous. This method will be discussed in a later section, as it is first essential to discuss and justify the representations that have been selected for mapping.

Mapping Representations

Scholars have already identified discourses on economic status, socialism, and the subjugation of ethnic minorities within Soviet and post-Soviet animation.[21] I have additionally identified discourses on sexuality and masculinity, the representations of which I will map in a selection of animated films thematically based on adaptations of folklore produced between 1950 and 2005. These five concepts serve as nodal points that contribute to the construction of representations of the female identity in films like The New Bremen Town Musicians, in which the dynamic that exists between the female villain, the innocent princess, and the male characters creates a striking image of valued behavior for women.[22] The discourses produced by the official government texts on representations of women have been supplemented by analyses that seek to account for how attitudes towards wealth, conformity, and the habitus of femininity were constructed. The folkloric model of analysis has overwhelmingly found women represented as submissive, overtly feminine, and as “yokels”, or unintelligent rural people.[23] This in turn contributes to another layer of discourse on socioeconomic status and mandated social practices.[24] Furthermore, the use and proliferation of specific colors serve as indicators of power within the gender hierarchy, as seen in mapping the color red across my primary sources.

Representations of the aristocracy and economic status identify the core and the periphery of society in terms of wealth; the middle-class is the core, and the very poor and very wealthy sit on the periphery.[25] Economic status serves as a traditional signifier within power relationships, and a gap in income becomes apparent between royalty and poor rural communities. This intertwines with the discourse on conformity, which explores an allegiance to social practice via repetition and compliance— this has been interpreted as a discourse on socialism.[26] Discourses on conformity and economic status jointly enforce an acceptance of inferiority within society, which I have found to be perpetuated further as an acceptance of inferiority by women in regard to their male counterparts. It is imperative to look at how the discourses on economic status, socialism, and the subjugation of ethnic minorities serve as facets of what constructs echelons of power and influence. As Fadina notes, “through the mediated constructions and representation of women the gender politics counteracted a move to equality, thus enabling the dominance of patriarchal hierarchy on and off screen.”[27] The additional identifiable discourses on sexuality and masculinity likewise play a role in the creation of systems of dominance, but play a more direct role in qualifying actions or visible attributes as positive, neutral, or negative femininity.

Contextual Framework

The absence of the faux-egalitarian doctrine of communism after 1989 partially accounts for ideological and subsequent behavior shifts among polity. Expanding upon these representations in the broader historical context of 1950 to 2005 provides a basis for the evaluation of the shift in animated thematic elements that parallel the ideological shift of the time period within post-Soviet states. In order to connect the two, it was essential to analyze how the discourses presented by the government, and later by independent animators, constructed meanings surrounding femininity and womanhood. Primary source selection was contingent upon both the popularity of the film and the time period in which it was produced. Soyuzmultfilm produced hundreds of films from the early 1950s until 1989 at the dissolution of the Soviet government, and thus a look at their most popular films focusing on folklore reveals an official government discourse on femininity.[28] For the purpose of investigating meanings associated with the content itself, I did not select films that are based on Russian or Ukrainian folklore, such as the poetry of Pushkin, for analysis. Instead I reviewed adaptations of stories by the Brothers Grimm or western European rural folklore.[29] This decision was made on the grounds that animated adaptations of national folklore tend to adhere closely to their written texts, and as such the visual imagery does not necessarily add any new meaning.[30] Tracing representations of the five aforementioned layers of discourse intertextually informs our understanding of what meanings are being constructed, in that repeated tropes and positive indicators become apparent across the board. Following the disbandment of Soyuzmultfilm, very few animated pieces based on folklore were produced and thus I have selected all produced between 1989 and 2005 for analysis of the following layers of representations.

Generation of Evidence

The films were viewed a minimum of three times each. The first round of viewing included the notation of which characters wear red and the duration of their time on screen. As explained by feminist scholar Kononenko, the use of red serves as an indicator of values by those opposed to royalty and, consequentially, in favor of communism. Kononenko’s argument is that the “good characters” who wear red are examples of purity and the ideals of citizenship.[31] During this first viewing, it was also noted what each character wore to pay notice to any changes in costume in future representations in films produced later. These observational data allow for a researcher to determine if a change in visual representation has occurred in multiple reproductions of a story over the course of several decades. In the series of films based off of the folklore of the musicians of Bremen, an originally German story, the clothing of the characters shifts drastically. My initial observations of the highly sexualized version of the female “baddie” leader in The New Musicians of Bremen, which was produced nearly four decades after its predecessor in 1971, indicated that clothing and exposure of skin would serve as an indicator of a shifting attitude.[32]

Within the analytical stages of my investigation, the application of the folkloric model of categorization contextualizes what meanings are evinced by this change in presentation, making it critical for me to carry out this process across all films. During the second viewing, I noted the characterizations of each character on the basis of their identifiable behavioral attributes, such as aggression, or docility, or rebellion. The means of identification have been provided by the folkloric model of analysis developed by Kononenko.[33] After this viewing, the identities were cross-referenced with the initial list of individuals who wore the most red. This was done in order to establish a relationship between behavior and the color of the clothing, including the presence of red, yellow, and green. Based on review of feminist scholarship, there are different meanings associated with these three colors, depending on if the wearer is male or female. Furthermore, color demarcation also correlated with socioeconomic status and power. This second viewing served as a time to note what characteristics within the folkloric model of analysis were present within each film. At this stage, characters were categorized according to this model as having a specific quality such as passivity. The third round entailed notification of specific words used by male characters towards female characters and vice versa such as to establish a relationship between them. Doing so utilizes the work conducted by linguists such as Prokhorov, who previously identified which colloquialisms are signifiers of inferiority.[34] This viewing laid the foundation for which analysis could be conducted after all data were collected, in which physical representation and language were integrated into creating a comprehensive representation of women.[35] A network of representations across the films presented itself as informing one another’s meanings in visual representation and rhetoric.

I have elected to model my classification system off of the feminist folkloric model of analysis developed by Kononenko as opposed to the Aarne-Thompson-Uther model of folkloric analysis due to the latter’s lack of systems of classification for aspects specific to femininity and the construction of gender.[36] Data analysis was conducted via NVivo, which classified data cases based on period of production and thus the producing agent. Again, films produced following the disintegration of Soyuzmultfilm in 1989 were compiled by independent animators with no affiliation to the government.[37] I created specific cases for each character that appeared in the film, categorizing them as follows:

Figure 1: Character Specification

| Bride (Female) | Hero (Male) | Hero (Female) | Villain (Male) | Villain (Female) | Witch (Female) |

I then established specific cases for characters that appeared in both Soviet and post-Soviet films. Each character was sorted into a case before being coded with the appropriate nodal points, as determined based on their representation in part of the film. The nodal classification included both their dialogue and visual presentation.

Figure 2: Nodal Classification

| Attitude | Femininity | Masculinity | Othering | Red | Sexuality |

The rationale for each node is as follows:

Attitude was classified as positive, negative, or neutral. This is in reference to the audience’s attitude toward a character and was determined by interpretation of the character’s role in any given scene. This could shift within a film— for example, attitudes towards a witch might be negative in the beginning, but through a plot of redemption, that shifts to neutral or positive. This interpretation is justified by Prokhorov’s rhetorical analysis, which identifies key words and phrases as positive, negative, or neutral, in conjunction with the application of Fadina’s classification of action as moral or amoral.[38] Femininity is classified by Schipper’s construction of feminine representation, which accounts for length of hair, style of clothing, mannerisms, and pitch of voice.[39] This classification was only applied to characters that overtly exhibited prototypical representations of femininity. This is not to be conflated with sexuality, which is later explained. Masculinity is also classified by Schipper’s construction of the masculine as it relates to the feminine within folklore and encompasses lack of emotional expression, physical show of strength, and exemplified bravery.[40] Like femininity, this classification does not encompass all male characters, but rather only those who align with the aforementioned traits. Sexuality is the codification of sexual expression or promiscuity as determined by the clothing, animated physique, and seductive actions of female characters. Sexuality is additionally used as an identifier for female characters who sought out their male romantic interest instead of vice versa. Othering, or the subjugation of ethnic minorities, is a classification of behavior or appearance that distinguishes a character as inferior on account of their ethnicity. This classification was established on the basis of rhetoric and action towards and by the character.[41] Factors that determine the “othering” of a character included the presentation of low intellect, impoverishment, and a rural setting. Red is further deconstructed featuring three subsets: Red, Red + Green, and Red + Yellow. Characters were submitted to a category simply based on the color of their clothing and accessories. This was done in order to identify patterns and subsequently analyze the implications of the use of color. Representations mapped on the basis of these classifications create a system of patterns from which meaning has been derived.

Analysis

Within the discourse on femininity and womanhood presented in Soviet animation between 1950 and 2005, I have observed two patterns of representation emerge regarding the use of the color red and the operationalization of sexuality. This advances Kononenko’s original claim regarding color theory through the incorporation of an adjusted methodology. Moreover, this analysis introduces the notion of female sexual prowess to the broader discourse, for which the academic consensus has previously determined that all folkloric women are portrayed as sexless.[42]

The Use of Red

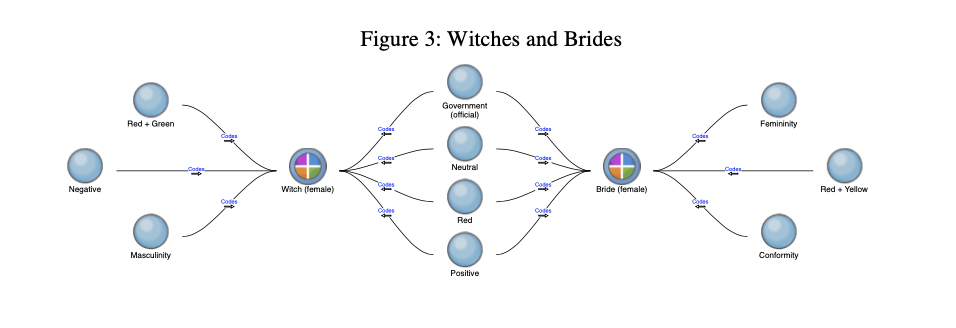

My first claim is that the use of the color red evokes themes of subjugation and submission through Soviet and post-Soviet animation due to its prolific use among marginalized characters. Red is thus an indicator of the submissive, depending on the degree to which it is being used to characterize appearance. In The Bremen Town Musicians, the princess serves exclusively as a love interest for the male protagonist, the Troubadour, and has no speaking lines.[43] She wears all red, silently complies with plot devices, and represents the ideal object of desire for both the protagonist and the audience.[44] This plot arch exists throughout the majority of animated folklore, and a dichotomy between female brides and witches is consistent throughout. Analysis of representations of both groups prior to 1989 yields a distinction between the colors that red was invariably paired with, as seen in Figure 3 below.

Red and yellow associate with brides, while red and green are present in representations of witches. This reveals two things: the first is that yellow and green, when paired with red, illicit meanings that contribute to the discourse on femininity. However, a pattern regarding the qualities associated with brides and witches, in particular what they share, forges an understanding of what attributes are valued. It is clear that attitudes towards witches and brides can be equally positive or neutral depending on the context of the text. For example, the witch in The Flying Ship helps the male hero impress the princess that he hopes to marry by vanquishing villains together.[45] However, the predominant pattern that emerges correlates negative attitudes with masculinity and femininity with conformity in reference to brides. The masculinization of witches’ features is perpetuated in all of the Soyuzmultfilm produced pieces (which is noted in the figure by the shared governmental, or official actor, producing the discourse) and implies that in breaking from the bridal character arch, they relinquish their femininity and womanhood. This concept will be addressed within my second claim, which will elaborate on how these nodal points construct gender.

Revisiting the primary claim with an awareness of the complementary attitudes and gendered attributes that the use of green and yellow perpetuate facilitates a greater understanding of their implementation. The economic stratification that exists within folklore yields three levels: aristocracy, peasant class, and subjugated ethnic minority.[46]The bride exists either on the aristocratic or peasant plane, while witches are presented similarly to persons who appear with darker skin tones and variants in textured hair.[47] Thus, yellow becomes associated with wealth and generally positive representations of female behavior. I interpret the correlation between the use of yellow/red and themes of conformity when explicitly applied to female characters to refer to the reinforcement of the value of submissive behavior. When women are portrayed positively in folklore they are following the rules outlined by their father, typically a king.[48] MacFadyen’s omission of a specific focus on female characters accounts for his generalization.

While yellow is indicative of higher social and economic status, green serves as its antithesis. The presentation of green/red with characters who are isolated, made a spectacle of, or evocative of negative attitudes reinforces the understanding that the behaviors of and values held by characters in green are not favorable. Ultimately, these layers generate a comprehensive account for how women in red are linked to inferiority to their male counterparts.

Red indicates an object of desire, with the desirable quality being subservience. I acknowledge that the meanings associated with the use of red evolve throughout the historical contextual framework of analysis. Red is also seen as a mechanism of representations of conformity and socialist ideology.[49] However, these themes can be simplified as the operationalization of subjugation under the pretense of faux-egalitarianism.[50] Thus when viewed through the theoretical feminist lens, this desired adherence to socialism in turn represents the hegemonic value of submission.[51] I am therefore able to support the claim that red is a signifier of valued passivity.

Disruption via Sexuality

My second claim is that sexuality is weaponized through the representation of sexuality as negative when, in the context of the scene, it disrupts the gender hierarchy. This disruption occurs due to the association of sexuality with masculinity in female characters.[52] I make this claim because contextually, sexuality is only overtly expressed by female characters that serve as an antagonist. Within The New Bremen Town Musicians, released in 2000, the leader of the “baddies”, or Ataman, is visually represented differently than in the first two films in which she appears, despite her possessing the same goal of overthrowing the king and taking his money for herself.[53] In this film, the third and final installment in the Bremen trilogy, she no longer wears red and is shown wearing clothing that exposes her skin and contextually resembles the paraphernalia of a prostitute.[54] She is now portrayed with more masculine facial features and on account of the alterations to her physical representation in addition to the negative rhetoric used towards her by other characters, I am able to categorize her as a villain.[55] This new presentation of a sexualized version of Ataman has usurped the hierarchy and thus her lack of submission withdraws her from consideration as a “real woman.”[56]

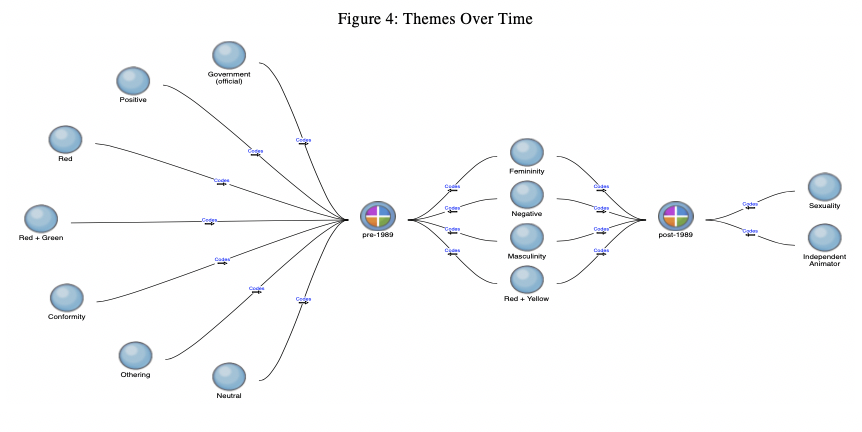

This is a repetitive theme explored by scholars who implement the folkloric model of analysis for characterizing the valued behavior of women in animated folklore.[57] It is seen here that women in Soviet and post-Soviet animation are not meant to be seen as sexual beings but instead must fit within a specific set of expected behaviors, and violating this is systematically discouraged. In Sister Alena and Brother Vanya, Alena pursues a romantic interest and is in turn drowned along with her brother Vanya by a witch, only to be saved by said heroic male.[58] Alena is forcibly reduced to her status of inferiority by the necessity of the rescue. Despite possessing some power over elements of the supernatural, witches reside at the bottom of the power hierarchy. This is conflated with conceptions of witches as a subjugated minority featuring a masculine or unattractive physique. Witches become subhuman due to their inability to be categorized among other female figures in folklore. The analysis conducted thus far has utilized films produced prior to 1989 due to the lack of folkloric adaptations produced following the collapse of Soyuzmultfilm, in part the result of the shift in thematic content of post-Soviet films.[59] Animated production of the post-Soviet era more closely resembled a commentary on the economic disarray of Russia in the 1990s, as well as a desire to stray from the minimalist style of animation renowned in the late 1960s in favor of cartoons in the vein of Disney.[60] Contextually, a general thematic shift is a nod to the region’s desire to move away from Soviet ideology deemed regressive. I posit that the pause on producing folklore effectuated an effort to separate media culture from tradition and the past. Only three folkloric adaptations were produced after 1989.

In Grey Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood, released in 1990, animators parody the demise of the USSR.[61] Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother fall victim to the wolf and are rescued by the huntsman, as per the original plot. Unlike traditional representations of the ailing grandmother and vivacious young girl, Babushka Theresa is voiced by a man, wears strikingly low-cut clothing, repeatedly hits Little Red over the head with a ladle and smashes Red’s head into a table.[62] This disruption of accepted feminine behavior in turn produces negative attitudes towards her, remaining consistent with the other films in this time period case classification.[63] Analyzing all of the women with speaking roles in each post-1989 film produces a similar result; the women are coded abrasive and unpleasant, sometimes referred to as such by other featured characters. Figure 2 on the previous page visually demonstrates the clustered characteristics shared by all female characters in Soviet and post-Soviet animation.

Adaptations produced prior to 1989 share a unique relationship between a positive discourse produced by the official actor. This does not indicate an overarching positive representation of female characters, but rather the glorification of compliant women who do not deviate from an expected pattern of behavior. Attitudes towards female characters fluctuate between positive and negative classifications depending on their role within a plot. Thus, a female character who does not exemplify the valued qualities of subservience and passivity will not be viewed positively by her fellow characters or an audience. Conversely, male characters maintain a level of liberty in their ability to deviate from traditional story arcs and still fluctuate between positive and neutral attitude classifications.

The introduction of independent animators after 1989 consequentially brings sexual expression to the forefront of the admonition of nontraditional females. The immediate implication of this pattern is that women who display aggression, through physical violence as with Babushka Theresa, or through ambition as with Princess Greta in the Wilhelm Hauff fairytale Little Longnose, are punished. This perpetuates the value associated with keeping women in their place, and reinforces aforementioned appraisal of quiet, one-dimensional women. I acknowledge that while this claim seems straightforward, it is more difficult to distinguish a clear pattern throughout all Soviet animation due to the overwhelming lack of female representation in conjunction with the rare use of overtly expressed sexuality in these texts. The New Musicians of Bremen is unique in its portrayal of women, first in that it portrays a woman as anything other than a mother or a love interest, in addition to its visual cues.

An argument against the validity of my claim could be made by pointing to this rarity as an invalid indicator of prevalent cultural models. I would refute this due to the contextual framework in which this work exists. The visibility of The New Musicians of Bremen is on average equivalent to that of the animated films being produced at the time. This film’s critical and commercial success must be seen as without relation to its two predecessors and instead compared to other primary sources that emerge following 1989. Given this, the content of the film can be viewed as an indicator of value systems with similar trustworthiness to other primary sources, thus making representations of Ataman a valid indicator of perceptions of sexuality. In considering each representation as valid, it is possible to postulate as to the effects of exposure to these meanings and ideas bolstered and preserved in animated media.

Conclusion

The discourse on femininity and womanhood in Soviet and post-Soviet animation exemplifies the value placed on submissive behavior by state and non-state producers and how specific rhetoric and visual cues perpetuate this idea as illustrated by the vilification and masculinization of femme characters who disrupted gender hierarchies in their respective narratives. I have advanced the claims of scholars who have reached similar findings in their research by broadening the scope of classification to create a more comprehensive understanding of how these themes were constructed. Understanding the mediums in which systems of values are ingrained within a culture and, furthermore, using animation as a signifier of cultural attitudes at any given time in history forges conceptions of how societies code and recode sanctioned behavior and build institutions. These representations contextualize how state and polity interact, in that the state can operationalize its ideological agenda via material investments which then influence the societal consciousness. The social authority of any state can be found in the minutiae of animated interaction, compelling viewers and scholars to be critical of the agency of media consumers in conjunction with critiques of manifestations of state ideology on screen.

My decision to pursue an interpretive research design in the interest of providing an analysis of how symbols can influence cognitive change and behavioral action may make it more difficult for other researchers to replicate my study, given the variances in interpretations for certain symbols. Thus, the trustworthiness could potentially be challenged, given my lack of expertise in Russian linguistics and my reliance on previous scholarship to label and organize specific behaviors of symbols. However, a thorough sense of Soviet cultural competence has been fostered by my upbringing by defectors of the USSR.[64] My fluency in conversational Russian, over a decade of exposure to Soviet animation, and the completion of multiple academic courses centered on Russian history have provided me with a broad understanding of both the region and the manner in which audiences interacted with the media that they consumed. In expansions upon this project, it would be beneficial to break down discourses on femininity in animated folklore based on content specific to a country so as to reduce the generalization of post-Soviet states as a single entity. The inclusion of an analysis of Soviet animated folklore without the parameters of the origin of the folklore would construct a more explicit representation of the culture of each post-Soviet state. This research is a fundamental exercise in turning to different vessels of communication as a means for explaining social phenomenon. Animated folklore that perpetuates the preference of passive women and the increase in the vilification of women who sought to upset the gender hierarchy in post-Soviet animation does not account for the stark decrease in the participation rate of women in government following 1989. There are grounds for the consideration of animated folklore as cultural documents that, when contextually framed by telos and cultivation theory, may serve as a facet of accounting for why the culture surrounding women in a position of legislative power changed.

Shayna Vayser is a BA/MA candidate at American University’s School of International Service, who completed her undergraduate degree in International Relations in 2019. Now a graduate student in the International Communication program, she is continuing her interdisciplinary research on cosmopolitan citizenship, race as technology, and global media governance. Her undergraduate work in gender construction and rhetorical analysis continues to inform her interest in integrating communications studies and theories of identity formation into the practice of state-building and media development, most recently explored in her work, “Women in Red: Femininity and Womanhood in the Soviet Union.” This research contextualizes contemporary Russian policies and attitudes towards women’s rights through an analysis of Soviet media.

References

Aarne, A. and Thompson, S. Types of Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography. Helsinki: Academia Scientarum Fennica. (1961).

Balina, Marina and Birgit Beumers. “To Catch Up and Overtake Disney?: Soviet and Post-Soviet Fairy-Tale Films”. Fairy-Tale Films Beyond Disney: International Perspectives. Routledge, (2015). 30-82.

Britsyna, Oleksandra, and Inna Golovakha-Hicks. 2005. Folklore of the Orange Revolution. Folklorica. (2005). 15-47.

Charland, M. “Finding a horizon and telos” Quarterly Journal of Speech. (1991). 2-22.

Chomsky, Noam. “Propaganda and Media”. Western Terrorism. Pluto Books. (2013). 31-33

Grossberg, L. “Marxist dialectics and rhetorical criticism” Quarterly Journal of Speech.(1979). 14.

Fadina, Nadezda. “Fairytale Women: Gender Politics in Soviet and Post-Soviet Animated Adaptations of Russian National Fairytales.” University of Bedfordshire. (2008). 1-367.

Flanagan, Scott C. “Media Influences and Voting Behavior.” In The Japanese Voter. Yale University Press, (1991). 297-331.

Grey Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood, Directed by Garri Bardin. Russia, 1990. Harris, Jonathan. “Leaning to Live with Pushkin: Pedagogical Texts and Practices.”

Greetings, Pushkin! Stalinist Cultural Politics and the Russian National Bard. University of Pittsburgh Press. (2016). 95-103. Kitzinger, Jenny. “The Debate About Media Influence.” In Framing Abuse: Media

Influence and Public Understanding of Sexual Violence Against Children. Pluto Books, (2004). 11-31

Kononenko, Natalie. “The Politics of Innocence: Soviet and Post-Soviet Animation on Folklore Topics.” The Journal of American Folklore 124, no. 494 (2011): 33-290.

Little Longnose, Directed by Ilya Maksimov. Russia, 2003.

MacFadyen, David. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges: Russian Animated Film since World War II. McGill-Queen’s University Press (2005). 8-167.

McKerrow, R. E. Critical rhetoric: Theory and praxis”. Communication Monographs. (1989). 2-15.

Neuman, Iver B. “Discourse Analysis.” Qualitative Methods in International Relations. St. Martin’s Press, LLC. (2008). 61-77.

Norris, Stephen M. “Animating the Past.” Blockbuster History in the New Russia: Movies, Memory, and Patriotism. Indiana University Press. (2012). 215-233.

On the Trail with the Bremen Town Musicians. Directed by Inessa Kovalevskaya. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1971.

Potter, W James. “The Linearity Assumption in Cultivation Research”. Human Communication Research. Vol 47, No 4. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. (1991). 562

Prokhorov, Alexander. “Arresting Development: A brief history of Soviet Cinema for Children and Adolescents.” Russian Children’s Literature and Culture. New York: Routledge.(2008). 55-160.

Schippers, Mimi. “Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony.” Theory and Society, vol. 36, no. 1. (2007). 85-102.

Sister Alena and Brother Vanya, Directed by Olga Chadatajewa. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1953.

Sloat, Amanda. The Civic and Political Participation of Women in Central and Eastern Europe. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development. (2004). 1-10.

The Bremen Town Musicians, Directed by Inessa Kovalevskaya, Yuri Entin, Vasily Livanov. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfiln, 1969.

The Flying Ship, Directed by Garri Bardin. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1979.

The Frog Princess, Directed by Mikhail Tsekhanovsky. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1954.

The Little Scarlet Flower. Directed by Lev Atamanov. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1952.

The New Bremen Musicians. Directed by Aleksander Gorlenko, Vasily Livanov. Produced by Vladimir Dostal. 2000.

Zipes, Jack. The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films. Routeledge. (2011).

Zompetti, Joseph P. “Toward a Gramscian critical rhetoric”. Western Journal of Communicatoin. (1997). 2-10.

[1] Sloat, Amanda. The Civic and Political Participation of Women in Central and Eastern Europe. (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development, 2004). 3.

[2] Norris, Stephen M. “Animating the Past.” Blockbuster History in the New Russia: Movies, Memory, and Patriotism. (Indiana University Press, 2012). 217.

[3] Kononenko, Natalie. “The Politics of Innocence: Soviet and Post-Soviet Animation on Folklore Topics.” (The Journal of American Folklore 124, no. 494, 2011): 142.

[4] Kitzinger, Jenny. “The Debate About Media Influence.” In Framing Abuse: Media Influence and Public Understanding of Sexual Violence Against Children. (Pluto Books, 2004). 13.

[5] Flanagan, Scott C. “Media Influences and Voting Behavior.” In The Japanese Voter. (Yale University Press, 1991). 322.

[6] Potter, W James. “The Linearity Assumption in Cultivation Research”. Human Communication Research. Vol 47, No 4. (Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 1991). 562

[7] Chomsky, Noam. “Propaganda and Media”. Western Terrorism. (Pluto Books, 2013). 32.

[8] MacFadyen, David. Yellow Crocodiles and Blue Oranges: Russian Animated Film since World War II. (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005). 44.

[9] Chomsky, Noam. (2013). 32.

[10] Balina, Marina and Birgit Beumers. “To Catch Up and Overtake Disney?: Soviet and Post-Soviet Fairy-Tale Films”. Fairy-Tale Films Beyond Disney: International Perspectives. (Routledge, 2015). 76.

[11] Prokhorov, Alexander. “Arresting Development: A brief history of Soviet Cinema for Children and Adolescents.” Russian Children’s Literature and Culture. (New York: Routledge, 2008). 122.

[12] MacFadyen, David. (2005). 132.

[13] MacFadyen, David. (2005). 28.

[14] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 127.

[15] Fadina, Nadezda. “Fairytale Women: Gender Politics in Soviet and Post-Soviet Animated Adaptations of Russian National Fairytales.” (University of Bedfordshire, 2008). 302.

[16] Britsyna, Oleksandra, and Inna Golovakha-Hicks. 2005. Folklore of the Orange Revolution. (Folklorica, 2005) 15.

[17] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 122.

[18] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 72.

[19] Zompetti, Joseph. “Toward a Gramscian critical rhetoric”. (Western Journal of Communicatoin, 1997). 3.

[20] McKerrow, R. E. Critical rhetoric: Theory and praxis”. (Communication Monographs, 1989). 4.

[21] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 44.

[22] The New Bremen Musicians. Aleksander Gorlenko, Vasily Livanov. Produced by Vladimir Dostal. (2000).

[23] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 115.

[24] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 142.

[25] Prokhorov, Alexander. 2008). 74.

[26] MacFadyen, David. (2005). 81.

[27] Fadina, Nadezda. (2008) 17.

[28] Norris, Stephen M. (2012). 217.

[29] Harris, Jonathan. “Leaning to Live with Pushkin: Pedagogical Texts and Practices.” Greetings, Pushkin! Stalinist Cultural Politics and the Russian National Bard. (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2016). 98.

[30] Fadina, Nadezda. (2008) 262.

[31] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 143.

[32] The New Bremen Musicians. Aleksander Gorlenko, Vasily Livanov. Produced by Vladimir Dostal. 2000.

[33] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 113.

[34] Prokhorov, Alexander. (2008). 122.

[35] Charland, M. “Finding a horizon and telos” (Quarterly Journal of Speech, 1991). 3.

[36] Aarne, A. and Thompson, S. Types of Folktale: A Classification and Bibliography (Helsinki: Academia Scientarum Fennica, 1961).

[37] Norris, Stephen M. (2012). 217.

[38] Fadina, Nadezda. (2008). 302.

[39] Schippers, Mimi. “Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony.” (Theory and Society, vol. 36, no. 1., 2007). 86.

[40] Schippers, Mimi. (2007). 88.

[41] Prokhorov, Alexander. 2008). 134.

[42] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 127.

[43] The Bremen Town Musicians. Inessa Kovalevskaya, Yuri Entin, Vasily Livanov. Soyuzmultfilm. 1969.

[44] The Bremen Town Musicians. Inessa Kovalevskaya, Yuri Entin, Vasily Livanov. Soyuzmultfilm. 1969.

[45] The Flying Ship, Directed by Garri Bardin. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1979.

[46] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 127.

[47] Britsyna, Oleksandra, and Inna Golovakha-Hicks. (2005). 33.

[48] The Little Scarlet Flower. Directed by Lev Atamanov. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1952.

[49] MacFadyen, David. (2005). 56.

[50] Britsyna, Oleksandra, and Inna Golovakha-Hicks.(2005). 24.

[51] Fadina, Nadezda (2008). 290.

[52] Fadina, Nadezda. (2008). 270.

[53] The New Bremen Musicians. Aleksander Gorlenko, Vasily Livanov. Produced by Vladimir Dostal. 2000.

[54] Fadina, Nadezda. (2008). 271.

[55] The New Bremen Musicians. Aleksander Gorlenko, Vasily Livanov. Produced by Vladimir Dostal. 2000.

[56] Fadina, Nadezda. (2008). 271.

[57] Kononenko, Natalie. (2011): 127.

[58] Sister Alena and Brother Vanya, Directed by Olga Chadatajewa. Soviet Union: Soyuzmultfilm, 1953.

[59] Norris, Stephen M. (2012). 217.

[60] Zipes, Jack. The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films. (Routeledge, 2011).

[61] Zipes, Jack. (2011).

[62] Grey Wolf and Little Red Riding Hood, Directed by Garri Bardin. Russia, 1990.

[63] Little Longnose, Directed by Ilya Maksimov. Russia, 2003.

[64] Neuman, Iver “Discourse Analysis.” Qualitative Methods in International Relations. (St. Martin’s Press, LLC., 2008). 68.

Published on January 16, 2020.