“Already three hundred times! The weight of these words can only be appreciated by those who know the full difficulty of our national development, the suffocation of the circumstances under which we came of age, and the oppression that pushed forward, as with other manifestations of the nation’s individuality, its art.”[1]

With these words, an anonymous author for the Czech newspaper National Pages (Národní listy), began his article celebrating a milestone: the three-hundredth performance of Bedřich Smetana’s opera, The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta), at the Prague National Theater in September, 1895. These two sentences, moreover, mark a crucial moment in the history of Central Europe, a moment when ethnic identities, imperial relationships, and the histories and cultures of entire peoples were being negotiated. Whether listening to singers at the opera house, participating in gymnastics competitions, or marveling at the exotic offerings of anthropological exhibitions, individuals and institutions were building identities in both explicit and subtle ways. As a part of the larger Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Czech lands of Bohemia and Moravia (today’s Czechia) were subject to imperial control from the Habsburg seat in Vienna. At the same time, the Czech lands were some of the most developed, literate, and industrially crucial provinces in the Habsburg Monarchy. Writers, musicians, intellectuals, and others therefore had to play a delicate game: while they lamented the “suffocating circumstances” of an oppressive regime, they also relied on and encouraged state-funded institutions to provide venues for cultural creativity in order to strengthen their claims to nationhood. Through their cultural achievements—including operatic ones—they argued both for their preeminence among the nationalities of the larger Habsburg Empire, and for greater autonomy within the empire itself.

Through my research on Czech opera, I investigate both Czech and Habsburg history to understand not only the ways in which political and social contexts influenced the creation of music, but also how musical events reflected changes in the concepts of race, ethnicity, and belonging. The three-hundredth performance of The Bartered Bride is an exemplary case study in this regard. First premiered in 1866, The Bartered Bride became the single most beloved of all Czech operas in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Critics and scholars praised the work as a symbol of Czech national character, emphasizing that its music flawlessly represented the essence of the Czech people, regardless of their education or class. By the early twentieth century, authors had published essays on topics varying from how Smetana’s female characters exemplified various characteristics of the ideal Czech woman, to how the joyous singing of the opening village chorus might be extended into a vision of moral philosophy. For these writers, the characters and social relationships found in the opera typified how the community of the nascent Czech nation should be structured

First premiered in 1866, The Bartered Bride was revised by Smetana several times. By the time its final form premiered in 1870, the opera was well on its way to dominance. In 1882, the National Theater celebrated its one-hundredth performance of the opera, with the composer present in the audience; he was to pass away two years later in May 1884. After Smetana’s death, writers, musicians, and institutions began, overwhelmingly, to canonize him as the founder of Czech music, and performances of his music likewise rose in status. The two-hundredth performance of The Bartered Bride took place in 1892, almost exactly ten years after the previous jubilee, and in a new production, no less. One month after the two-hundredth performance, the opera—in its original Czech—opened to rave reviews and international excitement in the imperial capital of Vienna as part of the International Exhibition of Music and Theater. The opera was quickly translated into German and began to make the rounds in European theaters. Meanwhile in Prague, Czech music critics rapturously celebrated the opera’s success, lauding it as the hope of Czech music’s entry into European (and indeed global) consciousness. They argued that it demonstrated Czech cultural and political maturity, especially since it had been so successful with the Viennese. Just over three years later, the opera would already be celebrating its three-hundredth performance, this time in conjunction with another epochal event: the Czechoslavonic Ethnographic Exhibition (Národopisná výstava českoslovanská), held in Prague in the summer and fall of 1895.

This accelerating timeline of operatic performance points toward a number of important developments. First among these was the growth of Czech audiences, which went hand in hand with the growing importance and reach of the Prague National Theater, which had opened permanently in 1883. Growth of Czech cultural life in general was also signaled by the explosion of exhibitions in the early 1890s; a new exhibition palace and grounds were constructed in the Prague district of Holešovice for the Jubilee Exhibition of 1891, celebrating the hundredth anniversary of Leopold II’s coronation as King of Bohemia (an event that Czech patriotic activists, illustrating the overlaps between nationalism and imperial influence, hoped Franz Josef I would echo). It was followed in 1892 by an exhibition of African artifacts collected by the Czech explorer Emil Holub. One month after Holub’s exhibition opened, the Prague National Theater and The Bartered Bride would triumph at the Vienna exhibition, and in 1895 the Czechoslavonic Ethnographic Exhibition—which featured multiple performances of The Bartered Bride—would attempt to hold a mirror up to the Czech nation itself.

Conceived in 1891, immediately after the Jubilee Exhibition, the Ethnographic Exhibition was intended to show the entirety of Czechoslavonic experience and ethnic character through cataloguing and exhibiting folk practices, costumes, objects from various institutions, music, and reconstructions of important places. Its organizers actively and self-consciously framed the event through an ethnographic lens, and their organizational efforts embodied a drive toward classification, schematization, and encyclopedic knowledge—an epistemological framework born of the imperial context of the exhibition and others like it. Classification, for the organizers, implied naturalness and validity: the heart of what the 1895 Exhibition attempted to showcase, including music. This is what the cultural theorist Anil Bhatti terms “colonial competence,” but just as such competencies could be developed by imperial rulers, so too could they be the purview of regional elites like those who organized the exhibition. Indeed, it was “part of the self-interest of the representatives of the new classified order and its beneficiaries to sustain the autocratically imposed system of classification and impart to it the status of being real and natural.”[2] By codifying a particular way of presenting Czech music for imperial and international consumption, exhibition organizers, the National Theater, and Prague journalists presented a classificatory system that, once accepted by imperial and foreign audiences, the Czechs themselves would want to perpetuate.

On September 25, 1895, in conjunction with the Ethnographic Exhibition, the National Theater staged the three-hundredth gala performance of The Bartered Bride. The exhibition orchestra even played a special concert that day at the palace and grounds showcasing other music by Smetana. Writers again focused on the idealized village life of the opera and how it accorded with the essential character of the Czech nation, but their rhetoric was intensified by the veneer of ethnographic “objectivity” at the exhibition across town and through the trappings of the production itself. Stage designers for the production, the same one that had been staged for the two-hundredth jubilee performance and in Vienna in 1892, had engaged self-consciously in ethnographic methods while creating the staging concept. They went so far as to travel to villages in Western Bohemia, make sketches of individuals and rural structures, and relay these back to Prague as inspiration for National Theater designers. Not only did this help to collapse the distance between the opera’s idealized world and perceptions of Czech ethnic character, facilitating its didactic potential, but it was also a practice that had a long history in European opera dramaturgy as a whole.

While all of these activities no doubt contributed to and popularized understandings of Czech national identity along ethnoracial lines, such explicitly nationalist efforts were at the same time tied up with larger imperial concerns. Officials connected to the larger Habsburg state apparatus actually supported the exhibition rhetorically, symbolically, and, most importantly, financially. Economic support was provided under the auspices of the Bohemian Diet, the regional governing assembly, and the diet president Prince Lobkovicz quietly supported the organizing efforts of the exhibition throughout its entire gestation. Ultimately the diet pledged a direct subvention of 60,000 Austrian gulden and established a guarantee fund of 100,000 gulden to support the exhibition. For comparison, the National Theater budgeted a maximum of 1,000 gulden for the entirety of its material contribution to the Ethnographic Exhibition.

The desire for greater state involvement was also evident among the Czech organizers. The main organizer of the exhibition, a journalist and playwright named František Adolf Šubert—who was simultaneously the director of the National Theater—emphasized the necessity of including both the Bohemian governor and a representative from the diet in the organization of the Ethnographic Exhibition at an exploratory meeting in 1891. The organizing committee eventually designated as honorary chairman of the exhibition executive committee Count Jan Harrach, a member of the Bohemian diet, former delegate to the imperial Reichsrat in Vienna, and president of what is today the National Museum. He was later joined on the committee by Count Jan Lažanský, who was serving simultaneously in the Reichsrat and the Bohemian Diet. By having a presence at Exhibition meetings, not to mention a financial stake in the event, these representatives of the Habsburg state apparatus could tacitly observe, guide, or possibly even co-opt the Exhibition.

For example, in another meeting, Count Harrach persuaded the organizers not to publicly announce their efforts to recruit Slovak contributors to the Exhibition. What is today Slovakia was at the time part of the Hungarian half of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Harrach’s caution to keep secret Slovak involvement was in part an effort not to antagonize the politically powerful Magyar nationalists in the Hungarian parliament. At the same time, this move prevented or at least delayed the growth of pan-Slavic feelings in the public arena by keeping separate two constituencies that might otherwise have banded together in creating nationalist headaches for the Habsburgs. By allowing the Ethnographic Exhition to proceed with their blessing, Habsburg officials could curtail the centrifugal pull of nationalist organizing, providing government support and thereby making themselves necessary for Czech cultural life. As Count Harrach was careful to point out at an early organizing meeting in 1891 regarding the emperor, “the same love that connects His Majesty to all [his] nations will of course powerfully and effectively contribute to the success of the Czech ethnographic exhibition.” If nothing else, the Habsburgs were keeping an eye on things.

The three-hundredth performance of The Bartered Bride in 1895 was part of a larger set of questions occupying not just Czech nationalists, but writers, musicians, and intellectuals across Europe. These questions were, ultimately, questions of power: who had the power to define the essential character of their own communities; which cities and which peoples had the power to define belonging, presenting themselves as centers to which events were reported; and who had the power to place themselves at the top of various cultural hierarchies, whether musical or racial? Through operas like The Bartered Bride and events like the Czechoslavonic Ethnographic Exhibition, Czech intellectuals advocated for their cultural maturity and attempted to claim a prominent position at the pinnacle of the cultural hierarchy of Central Europe. Nationalists and politicians in turn hoped that this would simultaneously demonstrate political maturity, and with it the ability to govern the Czech lands autonomously within a federated version of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Opera was but one facet of a broader discourse, however. In late April 1892, three years prior to the Ethnographic Exhibition and one month prior to the International Exhibition of Music and Theater in Vienna, Emil Holub’s South African Exhibition opened at the Holešovice palace and grounds. Holub was a Czech explorer who, inspired by figures like David Livingstone, spent more than ten years traveling through parts of southern Africa, collecting a variety of plant and animal samples as well as tribal artifacts. The exhibition in Prague (which had also been shown earlier in Vienna) displayed the fruits of his travels, showcasing a popularized, racially stereotyped, and deeply influential vision of the “Dark Continent” for curious audiences. Czech newspapers were astute in pointing toward the exhibition’s significance:

Let us not say that Africa is as Hecuba to us; science is the property of all peoples and the Old World will gradually not suffice for a growing population. He who contributes to the discovery of new productive natural sources, who searches for new ways of distributing and exchanging crops and products, or even new sites for colonization; to him belongs honor and recognition—and among African explorers, Dr. Holub has worked hard to earn this.[3]

The exhibition and its reception positioned Holub, and by extension the Czech people and their Habsburg rulers, at the forefront of African exploration and colonization. At the opening ceremony for this exhibition, the imperial governor even exhorted audiences to regard the exhibition as an opportunity for study, so that Africa might be made “useful.” Such rhetoric was but another way to position the Czech people at the upper reaches of yet another hierarchy: as a group that colonized rather than was colonized, with all the attendant ethnoracial assumptions that entailed in late-nineteenth-century Europe.

As we look back on all this cultural activity from our “Western” perspective in the early twenty-first century, we would do well to consider the ways in which practices like music can be mobilized for the purposes of nationalist agitation. Virulent ethnoracial conceptions of difference and otherness continue to lead to discrimination, violence, and mass death. It is imperative that we, as contemporary advocates of culture and cultural history, identify what our role has been in the shaping, creation, and dissemination of these ideas. More importantly, by revealing the constructive nature of nationalisms both historical and contemporary, we may indeed find ways to counter the ideas that justify horrific violence.

Christopher Campo-Bowen is an Assistant Professor/Faculty Fellow in the Department of Music at the NYU Faculty of Arts and Science. He completed his Ph.D. in musicology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. His research focuses on music in the Habsburg Monarchy in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially on the relationships between music, ethnicity, gender, and empire. He has published articles in the journals Nineteenth-Century Music, Cambridge Opera Journal, and The Musical Quarterly and presented at various national and international conferences. Christopher received a Fulbright grant for the Czech Republic to perform dissertation research; he also held a Howard Mayer Brown Fellowship from the American Musicological Society and was the recipient of a Council for European Studies Mellon Dissertation Completion Grant. He is currently a Provost’s Postdoctoral Fellow at NYU.

[1] “Již třistakrát! Váhu toho slova oceniti jen dovede, kdo zná celou tvrdost našeho národního rozvoje, dusivost poměrů, jimž bylo nám odrůstati, tíseň, která tlačila, jako jiné projevy individuality národa, i jeho umění.” “Hudba. Třisté provozování ‘Prodané nevěsty,’” Narodní listy, 27 September 1895, 6.

[2] See Anil Bhatti, “Heterogeneities and Homogeneities,” in Understanding Multiculturalism: The Habsburg Central European Experience, ed. Johannes Feichtinger and Gary B. Cohen, 17–46 (New York: Berghahn Books, 2014), 29.

[3] “Neřikejme, že Afrika nám jest Hekubou; věda jest majetkem všeho lidstva a stará země ponenáhlu nestačí pro rostoucí populaci. Kdo přispěje k poznání nových pramenů plodné přírody a hledá nové cesty šíření a výměně plodin i výrobků neb i osadnictví, tomu přísluší česť a uznání—a toho perně dobyl si mezi africkými cestovateli—Dr. Holub.” See “Jihoafrické výstava,” Světozor 26, no. 23 (22 April 1892): 276.

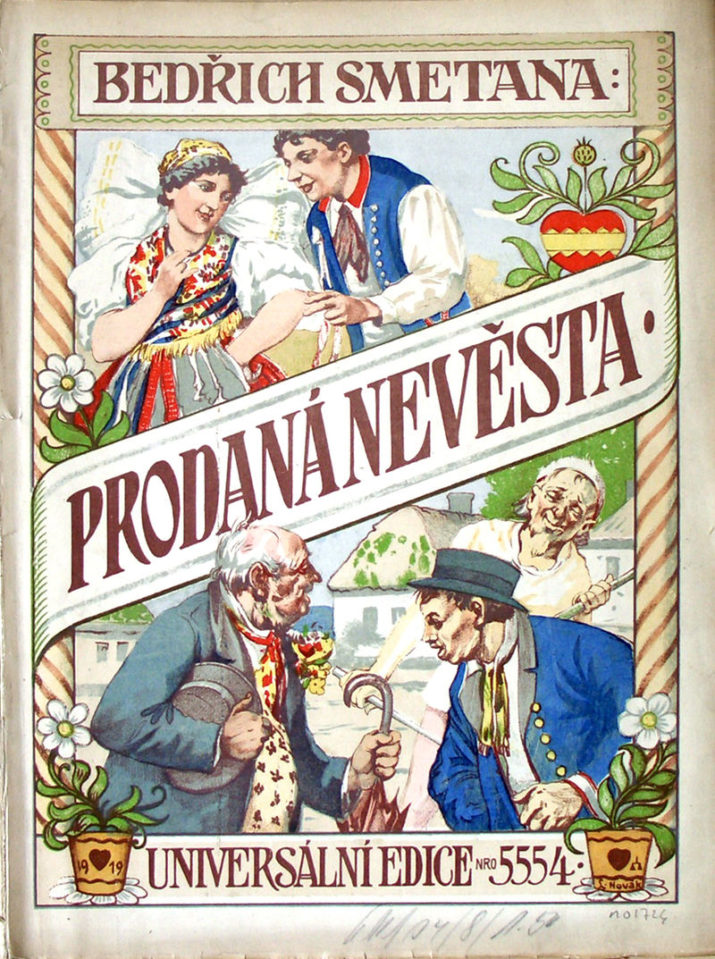

Photo: Colorfully illustrated cover of a Czech edition of the “Prodaná Nevěsta” score, published around 1919, depicting several of the opera’s leading characters | Shutterstock

Published on January 6, 2020.