“A medium is a technology within which a culture grows; that is to say, it gives form to a culture’s politics, social organization, and habitual ways of thinking.” (Neil Postman)

The bottom of the Web

In the aftermath of the insurgency of US president Donald Trump there was a great deal of concern regarding the problem of “fake news,” often imagined or assumed to be the work of exotic “Russian trolls.” While Russian interference was a minor factor in Trump’s election, the real message of these disinformation campaigns is perhaps one of media literacy—as what seems to have been understood is how to exploit the atmosphere of incivility, paranoia, antagonism and indignation that runs rife across the online forums and comment spaces that together comprise what has been called “the bottom half of the Internet.”[1] This article introduces some of the bizarre rituals and rhetoric of a radical right-wing culture war currently being waged in regions of the Web that are accessible, yet largely hidden from view.

Several years ago, I co-founded the Open Intelligence Lab with a group of young researchers at the University of Amsterdam, with the aim of studying the role of these online spaces in creating a new and distinct style of radical politics known as the “alt-right.”[2] Our research has involved empirical studies of the anonymous online discussion forum 4chan, a key component in a broader, subcultural milieu that we refer to as “the deep vernacular web.”[3] Once known as the subcultural source of many of the web’s best-known memes, in the period that saw the rise of Trump, anonymous posters from these fringe regions of the Web sought to promote bigoted propaganda often under the guise of mocking “politically correct” liberal speech culture. Our research suggests that some of these alt-right memes might move between the margins of 4chan and more mainstream right-wing discussion culture. The speculation is that this process may also occur through the medium of the unmoderated comment section. As explored below, an example of such an unmoderated comment section can be found on the extremely popular American hyper-partisan website Breitbart News, which might thus be conceptualized as an important, and generally overlooked, field of combat in the current online culture war.

#infokrieg

Although a decade ago 4chan was more generally associated with progressive activism—as home to the “Anonymous” hacker movement, which helped provide technical assistance during the Iranian Green revolution—recently 4chan activism has championed politicians on the radical populist right. Indeed, currently, few places online are as rancorous as 4chan, in particular its /pol/ (“politically incorrect”) discussion board, which rose to infamy alongside Trump and the alt-right as the staging ground for the so-called “Great Meme War” during the 2016 US presidential campaign. While 4chan users, or “anons,” enjoy cultivating a self-image of radical leaderless decentralization, in practice coordination tends to be managed by an in-group elite via chat applications. In the case of their involvement in the German elections, for example, anons used the “Discord” chat applications, (with channels named “Infokrieg” and “Reconquista Germania”) to share campaign tactics codified into “Information War” field manuals, as well as assigning faux-military titles such as “Übermensch Influencer” to participants with high numbers of Twitter followers.[4] While they failed in their fantasy of “meming” a European right-wing leader to become head of state—as they imagine themselves to have accomplished with Trump—these coordinated efforts did however arguably push AfD hashtags to the top of Twitter, possibly helping to contribute to the best showing for a far-right party in that country in generations.[5]

4chan’s technical design along with its subcultural preoccupation—which one researcher describes as “an absurd combination of teenage fantasies and fears”—have made the site extremely productive of various image-based memes, slang expressions and bizarre conspiracy theories that have been spreading virally through social media. [6] Since 4chan posts are anonymous, demonstrating one’s fluency in the latest version of a given meme is a key means by which posters to the board (or “anons”) show that they are in fact part of its community. As a result, memes and slang are constantly evolving. Couched in “ironic” humor, /pol/ anons engage in ritualistic forms of indignation and antagonism, which have provided an opening for the extreme-right to mobilize their agenda in the form of memes and slang that seem subcultural and “edgy” in other contexts (as opposed to racist). As a result, these vernacular innovations may come to resonate much more broadly outside of this relatively circumscribed “fringe” community, as a regular part of much more “mainstream” political discussions taking place on the radical, populist right.[7]

Rituals of righteous indignation

This idea of culture war is not new to the right. Indeed, historian of conservatism Corey Robin argues that the right has long sought to wage a counter-revolution against the leftist “enemy from below” whose objective is to extend equality, thereby perverting the natural order of things.[8] While Robin traces this struggle back to Burke, over the course of the past fifty years in the United States fringe elements on the right have developed the narrative of a left-wing bias in establishment news media. Today, the claim that national news broadcaster are in fact the purveyors of “fake news” has become a ubiquitous critique across the thriving “alternative” news ecosystems of many national webs—such as the Dutch YouTube political debate space.[9]

Many in America credit Andrew Breitbart, the founder of Breitbart News, as having inaugurated the current and distinctly apocalyptic phase of the right-wing culture war as “an extension of the Cold War that never ended but shifted to an electronic front”, in which “politics is downstream from culture.”[10] More than any other single individual Breitbart is most responsible for reversing conservatism’s longstanding uncool image, thereby laying the groundwork for the emergence of transgressive style of right-wing populism. Ironically enough, it was in fact the tactics of the New Left that initially inspired Breitbart, specifically Saul Alinski’s advise to the would-be radical “to bait the establishment so that it will publicly attack him as a ‘dangerous enemy’.”[11] In appropriating radical left tactics, the radical right populists thus aim to nurture a shared sense of victimhood—what Breitbart called “righteous indignation”—against a censorious liberal establishment obsessed with policing the boundaries of “politically correct” speech.

Similarly, in France new-right populists have conceptualized themselves as engaged in a “metapolitical” culture war also inspired by thinking on the left, specifically by the thought of Antonio Gramsci. In the aftermath of the failure of revolutionary socialism, Gramsci developed the concept of “cultural hegemony.” It meant the cultivation of a “collective will” out of otherwise diverse groups in civil society, via habits, customs and other forms of what he called “common sense”—a reactionary version of which is cultivated by the radical populist right as, for example, captured in the Belgian Vlaams Blok’s slogan “zeggen wat u denkt” [say what you think]. In relation to these tendencies in new-right thought, the argument proposed here is that the bottom of the Web can be conceptualized as a milieu that is conducive to growth and spread of expressions of ritualized indignation and what may be called “memetic antagonism”.[12]

Memetic antagonism

As an introduction to the cross-platform dynamics of this new online culture war, consider the case of the Pizzagate conspiracy theory. Pizzagate helped to redirect attention away from a damaging story concerning then candidate Trump to a narrative concerning the Clinton campaign’s involvement in pedophile sex trafficking centered on a pizza parlor, convincing one man to “self-investigate” the location at gunpoint. While the well-timed release of “dirt” on one’s opponent is nothing new to political campaigns, as far as we can tell, this counter-narrative was not created by the campaign, but rather it appears to have bubbled-up from the bottom of the Web. Indeed, our research found Pizzagate to have been created on 4chan/pol/ in the course of a single day, from which it was then picked-up by the alt-right Twitter celebrity Mike Cernovich (520K followers), and spread more broadly still by the InfoWars conspiracy theory YouTube channel (2.4M subscribers), only to finally appear on Sean Hannity’s Fox News program (3.2M viewers).[13]

Within certain online echo-chambers, Pizzagate resonated with common-sense suspicions long felt towards the Clintons. Insofar as they help to instill an atmosphere of innuendo and of slander into the broader political conversation, conspiratorial memes such as Pizzagate are effective weapons in an alt-right strategy of “reputation warfare.”[14] Instances of memetic antagonism such as Pizzagate are not meant to be objectively true. Rather they are designed for a media environment that privileges the types of us/them narratives that are the stock and trade of the radical populist right. As the Pizzagate pundit Mike Cernovich expresses the strategy: “We can control the narrative on Twitter.”[15]

In his recently published postmortem on the rise of the alt-right, Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation, journalist Andrew Marantz claims that figures such as Cernovich effectively exploited a key vulnerability in the attention economy constructed by Silicon Valley.[16] Marantz’s central argument is that the “engagement” metrics that drive social media reward “activating emotions” (such as fear and anger), which in turn create the perfect environment for the proliferation of bigoted propaganda. As Marantz notes, the alt-right sought to create outrageous and offensive memes that might generate “a surplus of activating emotion” (a tactic that trolls call “triggering”), thereby parasitizing their opponent as “host organisms” in order to spread their messages for free. One can see the same dynamic at work in the case of many of the most successful “fake news” stories, in which those whom found them objectionable or ridiculous were even more likely to spread the meme.[17] Many were unprepared for the alt-right’s “attention hacking” tactics, and as a result of this journalists often unintentionally helped to amplify their messages, a lesson that has taken longer to arrive in Europe.[18] (Indeed, on numerous occasions in my own research I have found myself trying to dissuade journalists from covering the alt-right’s latest attempts to spread their memes.)

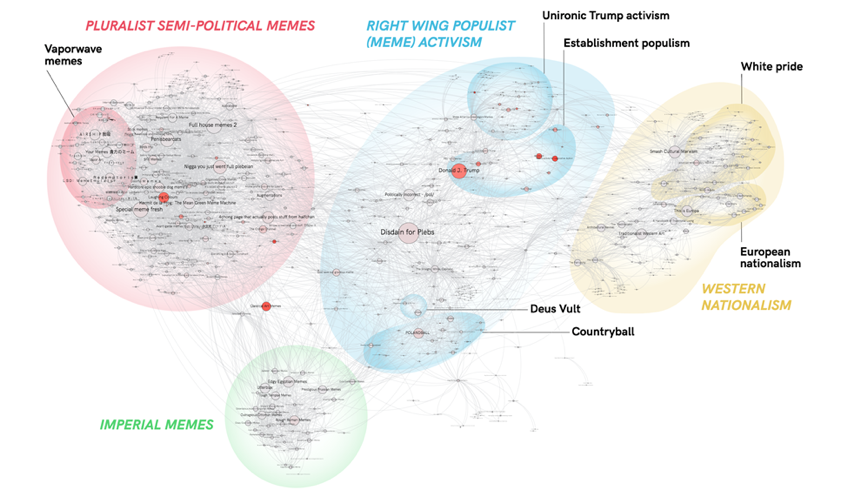

Fashy Facebook, c-2017 (OILab)

Another particularly successful alt-right culture warrior whom Marantz profiles is Mike Enoch. Further to the extreme-right than Cernovich, Enoch started the Facebook page “Fashy Memes”, which he claims spawned many other alt-right meme Facebook pages.[19] In early 2018, the Open Intelligence Lab created a “like network” depicting how alt-right memes had proliferated on Facebook, with thousands of such pages devoted to imagery of imperial glory, Western and European nationalism, white identity and peculiar genres such as countryball, which offers a kind of adoring user-generated parable on the rise of right-wing populism in Europe.[20] Maps such as this seem to challenge an article of faith, once quite common to our field, that dispersed, decentralized, and easily available communications technologies would lead to an embrace of cultural diversity and the efflorescence of other such liberal democratic ideals. Most of these pages were however relatively small and obscure with the notable exception of that of Donald J. Trump and in particular Breitbart News, the comment section for whose website was—as we will now see—a central stage of battle in the Great Meme War.

Comments as a memetic medium

While there is a large body of literature that seeks to answer the question of why radical right populism has emerged at this particular moment of history, there is a paucity of empirical research concerning the dynamics by which the rituals of indignation and antagonism as described above travels from the fringe to the mainstream. One of the few exceptions here is the analysis by Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts of how, in the course of the 2016 US presidential election, the term “globalist” spread from its apparent origins on a white nationalist website, via articles on the website of Breitbart News, ultimately to appear in a New York Times story—written by a reporter who was apparently oblivious to the term’s dubious etymology.[21] By analyzing occurrences of the term in articles from across the political spectrum before it had been popularized by Breitbart journalists, Benkler et al. argue that, originally, “globalist” had clearly been an anti-semitic “dog-whistle.”

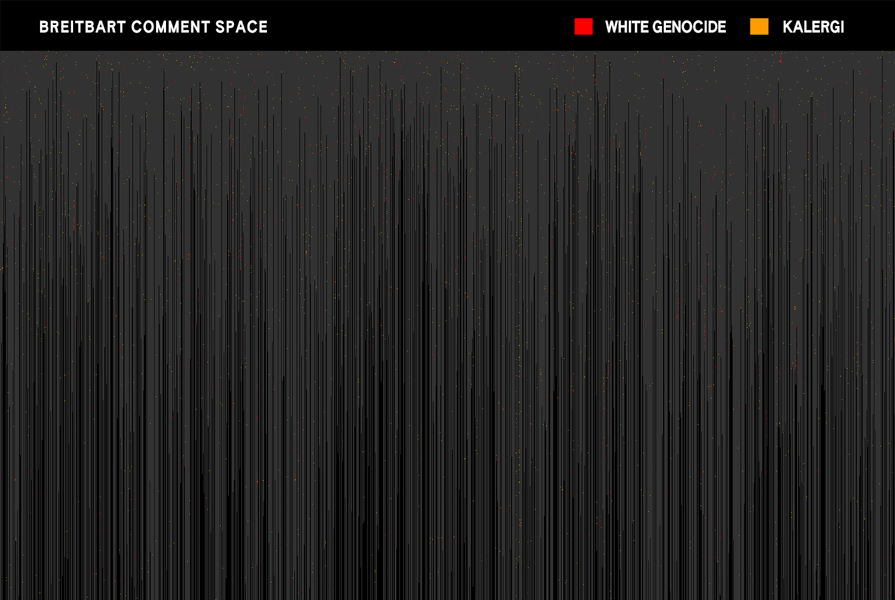

Benkler et al.’s broader analysis concerns how a network of alternative right-wing news sites anchored around Breitbart News succeeded in keeping the media narrative focused on the issues of Islamophobia and of immigration to the benefit of the Trump campaign.[22] In adopting a traditional political communications approach, concerned with “framing and agenda-setting,” Benkler et al. however overlook the significance of the role of comment space. Unlike almost any major newspaper yet akin to many social media sites Breitbart, as it turns out, had an extremely lax moderation policy during the period that, according to Benkler et al., it helped to steer frame media’s agenda on the topics of Islamophobia and immigration. In scraping Breitbart’s comment space from the same period of time analyzed by Benkler et al., one is struck by the frequency with which posters used many of the alt-right slang expressions developed an popularized by /pol/ anons and white nationalists.[23]

Breitbart comments graphic, May 2016-May 2017 (OILab)

While discussions of the Pizzagate conspiracy theory do appear with some frequency in Breitbart’s comment space, perhaps more compelling for a European audience are the cases of “white genocide” and “Kalergi”. Discussions of “Kalergi” concern a conspiracy theory alleging that an early advocate of European unification (Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi) had a secret plan to instigate the “biggest genocide in human history” by “breeding-out… indigenous Europeans” and “the encouragement of mass non-white immigration.”[24]Similarly, “white genocide” is an alt-right meme expressing the idea that “the international Jewish system, the capitalist system and the forces of globalism seek to erase the European people”—in words taken from apromotional video for the alt-right’s 2017, “Unite the Right” rally.[25] While these terms did not appear in any of the Breitbart’s articles, their persistent use in the comment space demonstrates how even mainstream (if hyper-partisan) news organizations can function as discussion forums for normalizing extreme-right frames.

The post-meme war era

Gradually, since the election of Donald Trump, and with increasing momentum in 2019, public sentiment has shifted against Silicon Valley for their purported role in creating conditions favorable for the growth and spread of the reactionary nonsense that seems to benefit the radical populist right. In the conclusion to his analysis of the rise of the alt-right, Andrew Marantz argues that it is unlikely that this change in public sentiment would have occurred had Trump not won and Brexit not occurred. In the past few years many alt-right outlets—including InfoWars in the US and Red Ice TV in Sweden—have been “de-platformed” by social media, thereby dramatically limiting the size of their audience. As our research has shown, in the course of the last year, much of the extreme content on YouTube, for example, has now been deleted—leading, in turn, to the proliferation of a host of “alt-tech” sites.[26]

In spite of the fact that many of the egregious online extremists may have been censored, according to Marantz, in the past few years the alt-right have nevertheless succeeded in opening the “Overton window” of socially acceptable opinion to the extent that statements of bigotry that would have seemed unimaginable to many only a few years ago are now regularly expressed by radical right politicians.[27] What social media platforms offer these politicians is the capacity to attune their messages to resonate with reactionary tone of anti-PC discussion that thrives at the bottom of the web. Since the time of Burke part of the right’s strategy to defeat the left has been to study and copy their tactics. While this bicameral left/right metaphor is inadequate to address the contemporary populist problematic, it is nevertheless important for those who identify with the left to study the new right’s memetic rituals of indignation and antagonism. At the same time, it is equally important, however, not to follow them down that perilous path.

Marc Tuters is an Assistant Professor affiliated with the Digital Methods Initiative and the director of the Open Intelligence Lab at the New Media and Digital Culture program of the University of Amsterdam where his research focuses on radical online subcultures.

References

[1] Reagle, Joseph M. 2015. Reading the Comments: Likers, Haters, and Manipulators at the Bottom of the Web. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

[2] While this term was originally coined to describe Anglo-American movements primarily based online, it has been it has more recently been extended to the European context, as indeed have their online culture war tactics. See: Waring, Alan. 2019. The New Authoritarianism: Vol. 2: a Risk Analysis of the European Alt-Right Phenomenon. Stuttgart: ibidem.

[3] de Zeeuw, Däniel and Marc Tuters. 2019. “The Internet Is Serious Business: on the Deep Vernacular Web and Its Discontents.” Cultural Politics. (forthcoming)

[4] Pomerantsev, Peter. 2019. This Is Not Propaganda: Adventures in the War Against Reality. London: PublicAffairs. p.67

[5] Davey, Jacob, and Julia Ebner. 2017. The Fringe Insurgency: Connectivity, Convergence and Mainstreaming of the Extreme Right. London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue. p. 19-24

[6] Uitermark, Justus. 2017. “Complex Contention Analyzing Power Dynamics Within Anonymous.” Social Movement Studies 16 (4): 403–17.

[7] While the majority of posts to 4chan/pol/ do originate from Anglo-American ip addresses, many posts also come from Germany, Netherlands, Sweden and France amongst other European nations.

[8] Robin, Corey. 2011. The Reactionary Mind: Conservatism: From Edmund Burke to Sarah Palin. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[9] Tuters, Marc. 2019. “Fake news and the Dutch YouTube political debate space” Rogers, Richard, and Sabine Niederer (Eds). The Politics of Social Media Manipulation. Amsterdam: Report for the Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. pp 152-166

[10] Breitbart, Andrew. 2011. Righteous Indignation: Excuse Me While I Save the World. New York: Grand Central Publishing. p. 3

[11] Alinski, Saul. 1971. Rules for Radicals: a Pragmatic Primer for Realistic Radicals. New York: Random House. p. 100

[12] Tuters, Marc, and Sal Hagen. 2019. “(((They))) Rule: Memetic Antagonism and Nebulous Othering on 4chan.” New Media & Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819888746

[13] Tuters, Marc, Emilija Jokubauskaite, and Daniel Bach. 2018. “Post-Truth Protest: How 4chan Cooked Up the Pizzagate Bullshit.” MC Journal 21 (3). http://journal.media-culture.org.au/index.php/mcjournal/article/view/1422.

[14] Rosamond, Emily. 2019. “From Reputation Capital to Reputation Warfare: Online Ratings, Trolling, and the Logic of Volatility.” Theory, Culture & Society 0 (0): 1–25. doi:DOI: 10.1177/0263276419872530

[15] Cernovich and others had developed these manipulation techniques in the “pick-up artist” scene, which had grown in popularity in the late-2010 by teaching “beta males” how to seduce women through “controlling the frame.” Indeed, as Marantz notes, it was in large part Trump’s “alpha male” public image that politicized many young men previously uninterested in parliamentary politics, including Cernovich himself.

[16] Marantz, Andrew. 2019. Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation. New York: Viking.

[17] boyd, danah. 2018. “You Think You Want Media Literacy… Do You?.” Lecture at South by Southwest. March 9. https://www.sxswedu.com/news/2018/watch-danah-boyd-keynote-what-hath-we-wrought-video/

[18] Phillips, Whitney. 2018. The Oxygen of Amplification: Better Practices for Reporting on Extremists, Antagonists, and Manipulators Online. New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

[19] On their website The Right Stuff, Enoch and his colleagues promoted the phrasal meme “((()))”, used as an anti-semitic harassment technique used to target journalists on Twitter. While he was was a committed “white nationalist”, Marantz reports that Enoch initially claimed that his anti-semitism began as a “joke” primarily intended to shock. Soon, however, he found himself hemmed-in by the committed anti-semitism of anons on 4chan/pol/.

[20] Hagen, Sal. 2018. “From Vaporwave to Penisbearcats: Facebook’s Vernacular Meme Neighbourhoods.” OILab. February 22. https://oilab.eu/from-vaporwave-to-penisbearcats-facebooks-vernacular-meme-neighbourhoods/ (Note that Facebook has since shut down its API making it practically impossible to create a map of this granular detail).

[21] Benkler, Yochai, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts. 2018. Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp 105-144

[22] Especially in the aftermath of the European refugee crisis these same issues have worked to unite the right in Europe, often towards the ends of an atavistic idea of a Europe, which appears paradoxical given their frequently vehement anti-EU stance.

[23] In the best case we might posit that these commenters are ignorant of origins of these terms, as in case of the reporter mentioned above. More troublingly they may be aware of how these terms resonate on the extreme-right, thereby assenting to their politics by adopting their vernacular.

[24] These words are actually quoted from a speech given to members of the European Parliament by the British National Party MEP Nick Griffin. For more on the Kalergi Plan conspiracy. Aee: Thorpe, Benjamin James. 2018. “The Time and Space of Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-Europe, 1923-1939.” PhD dissertation. University of Nottingham.

[25] Elements of this same white nationalist narrative also appeared in the manifesto of the Christchurch New Zealand mass shooter, who presented his murder of fifty-one Muslim worshippers in the spring of 2019 as a defense of “the European people.”

[26] OILab. 2019. “4chan’s YouTube: a Fringe Perspective on YouTube’s Great Purge of 2019.” OILab. June 17. https://oilab.eu/4chans-youtube-a-fringe-perspective-on-youtubes-great-purge-of-2019/

[27] Recently, for example, following his party’s strong showing in the 2019 Dutch provincial elections, the radical right, populist politician Thierry Baudet, evoked the spectre of an endangered “Boreal people,” which was widely considered to have been a white nationalist dogwhistle.

Photo: Fake news on internet in modern digital age | Shutterstock

Published on January 16, 2020.