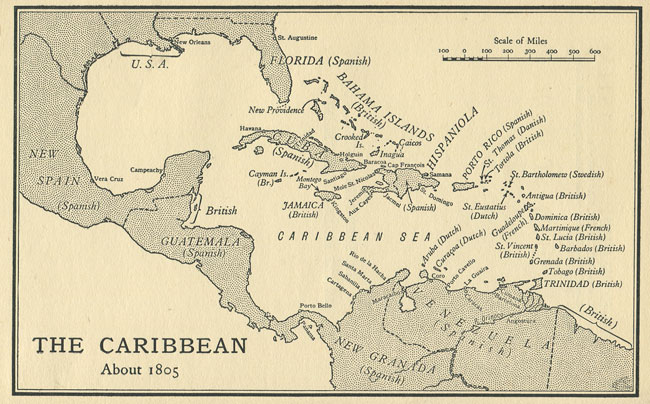

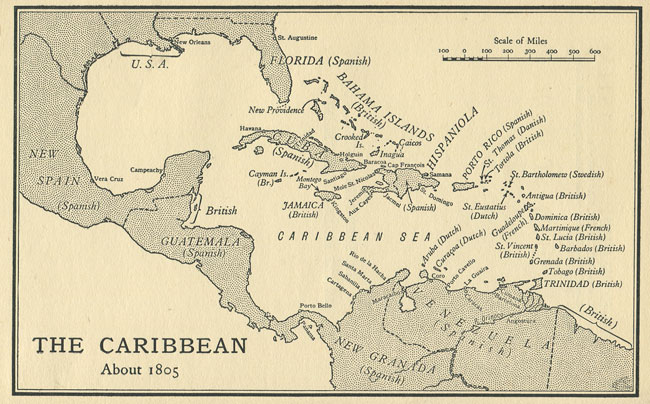

When first formalizing my research plans in early 2018, I conceived of my project concerning the British Free Port Act of 1766 to be about emulation and idea-sharing between various European empires in the Caribbean. This specific act opened up six British Caribbean ports (four in Jamaica, and two in the island of Dominica) to trade with foreigners—the first time in over a hundred years that foreign ships could legally enter any British colonial harbor. Why did Britain liberalize its Atlantic commercial network at this time? The Dutch had established their own free ports at St. Eustatius and Curaçao in the early eighteenth century, the Spanish opened up Monte Cristi in what is now the Dominican Republic in the 1750s, the French created temporary free ports at St. Lucia, Martinique, and Guadeloupe in 1763, and the Danish allowed foreign merchants to trade in their islands of St. John and St. Thomas starting in 1764. Were the British copying these successful reforms? I began my research over the summer expecting to find British policy-makers drawing upon these free port models in their arguments for the Free Port Act of 1766.

Naturally, I realized the picture was much more complicated than merely a story of emulation. I began my summer research by looking in the Parliamentary Archives, the National Archives, and the British Library in London. These archives contained various drafts and the final version of the act; petitions, complaints, and proposals made to Parliament members by merchants, colonial officials, and domestic manufacturers; internal correspondence by MPs and other British decision-makers; and reports on the debates concerning British commercial policy in 1766. I then made a trip to the Sheffield City Archives, which holds most of the records of the British Prime Minister at the time, the Marquess of Rockingham. There, I found relevant personal correspondence between Rockingham and the members of his ministry, as well as a wealth of letters of appreciation and thanks to Rockingham by British manufactures and merchants for his work in passing the Free Port Act.

In sifting through all of these documents, I did uncover evidence that certain British policy-makers considered other free ports as models for successful commercial reform. In particular, observers marveled at the prosperity of the barren Dutch island of St. Eustatius. For instance, Francis Moore reported to Parliament that the Dutch received enough French West Indian produce (sugar, rum, and molasses) “sufficient to load 40 or 50 large ships yearly” and that the Dutch sold £100,000 worth of cloth, as well as high quantities of enslaved peoples and fish, every year to French and Spanish customers through this port.[1] But rather than merely emulating other empires’ successes with free ports, the Rockingham Ministry used the fact that the Dutch, Spanish, Danish, and French had instituted free ports to justify their own creation of these open harbors. Other empires could not complain that Britain was establishing free ports since they themselves had done so already. And such a justification was needed to sooth potential inter-imperial tensions since the British envisioned that their free ports not only would emulate rival ones but also destroy them. When Parliament interviewed several merchants in the winter and spring of 1766 while it was considering the passage of the Free Port Act, many testimonies argued that British free ports would divert trade from the Dutch St. Eustatius (aka “The Golden Rock”). A British free port act, one commentator said, would thus have “the End and Design of Rivaling the Dutch” and could finally “ruin” “that curs’d Rock.”[2]

Another interesting strand of reasoning for British free ports is what I deem “virtual conquest” arguments. Many Britons envisioned that when foreigners came to trade in British Jamaica and Dominica they would become dependent on British goods. Thus, foreign colonies, such as Spanish Cuba and French Martinique and Guadeloupe (which the British had conquered in the Seven Years War from 1756-1763 but relinquished in the 1763 Peace of Paris), could become economic possessions of the British empire. With this line of reasoning, British MP John Huske asked the rhetorical question in 1765, “does not the supplying foreign Colonies with what they want, and taking from them what they produce, so far as this extends, make them the Colonies of Gr. Britain, and this too without the expence [sic] of supporting or defending them?”[3] Free ports, supporters argued, could act as “weapons” in the extension of the British empire, enabling London, without cost in blood or gold, to gain more “subjects” who would readily purchase British manufactures and supply Great Britain with needed raw materials.

Finally, my research findings pushed back against a dominant strand in the, albeit limited, historiography on the British Free Port Act of 1766. Scholars such as B.D. Bargar, Paul Langford, Richard Bourke, and Nancy Koehn have interpreted the Free Port Act as a move towards “free” inter-imperial trade in the British empire and a fundamental break in Britain’s “mercantilist” or closed system of commerce ruled by the Navigation Acts from the seventeenth century.[4] These historians state that establishment of the British free port system marked an early moment in what would come to be known as “free trade,” i.e. deregulated commerce between various nations intended to benefit all parties that diverged from the fundamental principles of the Navigation Acts, which sought to direct trade to benefit Great Britain exclusively. But my research has shown that the Rockingham ministry’s motivations concerned the relative power and wealth of Great Britain over her rivals rather than the absolute wealth of most of its subjects, and particularly its colonists. The administration meticulously crafted the act, in terms of the goods that could be bought and sold, not to help British colonists gain riches explicitly and unequivocally. Parliament would open up trade primarily to benefit Great Britain’s merchants and manufacturers and at the expense of other empires, as the “virtual conquest” arguments demonstrate. Economic thinker William Hargraves captured this mentality when he wrote to Rockingham directly in March 1766 and stated that while he was “very fond of the Act of Navigation” he believed “a little alteration would be very advantageous” namely that “our Colonies may have liberty to export our manufactures and merchanize [sic] imported from Great Britain in Foreign Bottoms.”[5] The Free Port Act did just that. The purpose of this legislation was to advance British domestic mercantile and manufacturing interests, and did not preference the colonies’ economies. While diverging slightly from the “letter” of previous laws, the motives being this reform were consistent with the “spirit” of the longstanding Navigation Acts.

There exist multiple strands for where this project could go, beyond the article that I have written detailing these reasons behind the Free Port Act. If this act really conformed to the “spirit” of the Navigation Acts, unlike many historians have supposed, it may fit in with the pre-Revolution narrative of unpopular British colonial legislative reforms that stoked animosities in British North America, which eventually resulted in rebellion and independence by colonists who felt unfairly maligned and increasingly controlled by the British metropole. Notions of free ports’ potential for the “virtual conquest” of spaces beyond Britain’s political control may help trace a genealogy of considerations regarding Britain’s so-called “informal empire” of free trade in Latin American countries in the nineteenth century. And finally, the dual mentality of emulating rival free ports in order to destroy them can shed light on this wave of commercial reforms occurring in the Caribbean in the 1750s and 1760s. While, on the surface, it may seem like a time of idea-sharing and increasing commercial connections, the establishment of British free port was also steeped in jealousy, competition, and a desire for economically ruining rivals. This movement resembled more of an arms race than a moment of peaceful collaboration and integration. Did Spanish, French, and Danish policy-makers share this jealous emulation mindset when instituting their free ports?

This project has opened up and illuminated questions concerning motivations for the United States’ foundation, Britain’s strategy of “informal” empire in Latin America, and the development of “freer” forms of commerce in the cosmopolitan Caribbean. I hope to explore these areas of investigation further in my dissertation, with my analysis of the British Free Port Act of 1766 standing at the center of this research.

R. Grant Kleiser is a Ph.D. student studying the early modern Atlantic world at Columbia University. He is working on a dissertation topic concerning the British Free Port Act of 1766, its inter-imperial practical and intellectual origins, and its effect on the American Independence movement, new conceptions of British political economy and commercial imperialism, and subsequent theories regarding free trade. He is generally interested in smuggling and counter-contraband policies, reforms, and reactions throughout the French, Spanish, Portuguese, and British imperial spheres.

This research is sponsored by the Alliance-CES Pre-Dissertation Research Fellowship funded and awarded in collaboration by Alliance and the Council for European Studies (CES) at Columbia University.

[1] Francis Moore, “Thoughts on the Expediency of Opening Free Ports in Dominica, by a Person who Resided some years at the Island of St. Eustatius,” May 1766, British Library (BL), Add. Ms. 33,030, f. 253.

[2] See Edward Davis to Marquess of Rockingham, undated (ca. 1766), Wentworth Woodhouse Muniments (WWM) Rockingham Papers (R), 37/4.

[3] Mr. Huske’s Scheme for Free Ports in America,” ca. 1765, BL, Add. Ms. 33,030, ff. 318-323.

[4] B.D. Bargar Lord Dartmouth and the American Revolution (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1965), 38; Paul Langford, The First Rockingham Administration, 1765-1766 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973), 207; Richard Bourke, Empire and Revolution: The Political Life of Edmund Burke (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015); and Nancy Koehn, The Power of Commerce: Economy and Governance in the first British Empire (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994). Bourke and Koehn go so far as to say the Free Port Act undermined and challenged the very principles of the Navigation Acts.

[5] William Hargraves’ Dissertation on Trade, March 22, 1766, WWM/R/96/2, f. 34.

Published on January 16, 2020.