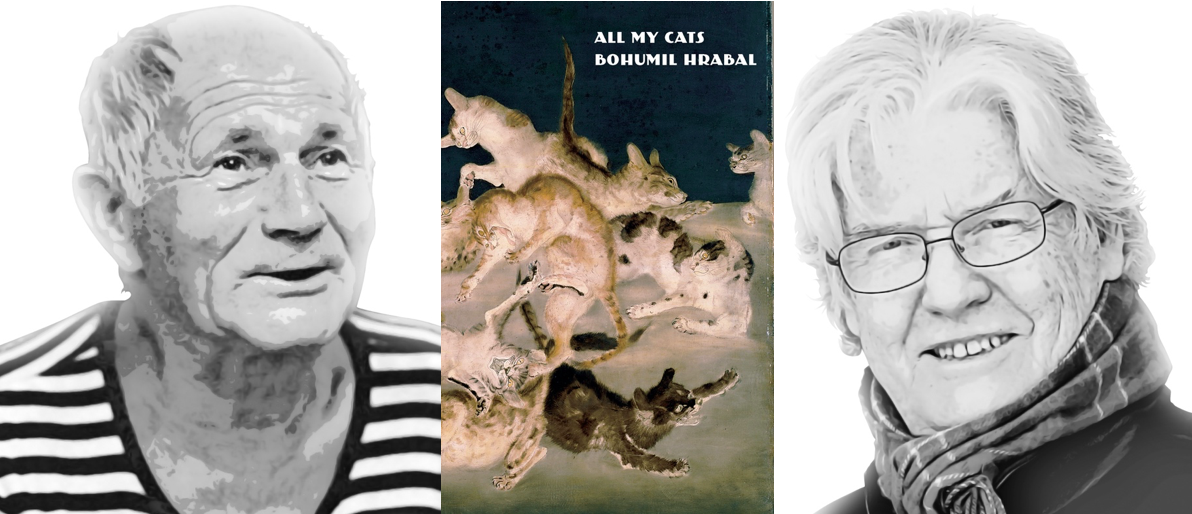

Translated from the Czech by Paul Wilson.

Back then, I went to the movies in Semice, where they were showing Mr. Fellini’s La Dolce Vita. As soon as Steiner appeared –– a handsome man playing the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor –– and then when I saw his wife and children, I began to feel queasy, and when it came to the scene where the paparazzi shoot Mrs. Steiner with their cameras as she comes home from shopping, and when I saw those two children lying in their apartment, shot dead, and their father and murderer, Mr. Steiner, lying dead by his own hand in his armchair, I began to tremble and had to get out, so I pawed and clawed my way from the center of the row just to get away from there. Mr. Steiner had been as terrified as I was for the future of his children and he killed them just as I killed those kittens, and the stray cat that winter evening, except that I had foolishly decided to remain in this world, and not to take my leave of it, as foretold by Mařenka, who died and left behind the large handbag with the green handles in which my grown-up kittens would often play or sleep, a memento of her prophecy. And just as I had once suffered from chronic stomach pains, it was now my heart that ached, because my soul was sick, as was Dr. Steiner’s, or Raskolnikov’s, when he murdered those two old women, foolishly believing that it would mean no more than killing two human lice.

One Sunday afternoon Blackie came down with a temperature. She jumped out of the basket where the kittens were and ran to me, shivering with the fever and I stroked her but she began to writhe in convulsions. At first, I wanted to put her back in the basket and take her straight to the vet in Ř.čany, but she clung to me, pressing herself against me, then lay down while I stroked her gently and she was so damp with sweat she looked as though I’d pulled her out of the river. Then my wife came and urged me to take Blackie to Ř.čany, but I felt Blackie would get over it and besides, if we took her by car now, she could go berserk and start clawing at us, because she was starting to become unhinged. The fever had addled her, and I was convinced that, as will happen to dogs, she had distemper and the disease had given her convulsions.

And sure enough, Blackie stopped paying attention to me, and then she began clawing at me and I had to take a rag, and then a blanket, and hold her down. So violent were her convulsions that it was like trying to hold on to a live carp and I could feel that she was slippery with sweat.

And so I held her down, pinned her to the floor and called out to her and swore to her that I was right there with her, but she howled and spat and hissed at me as though she’d discovered that it was me who’d killed her babies, that I was the guilty one, that my hands were steeped in blood, and that the hands she had once so loved now terrified her, and the realization of all that had driven her mad. The longer I held her down, the greater was my fear that, because she was so strong, if she slipped from my grasp, she would fling herself at me, so I pushed down harder and harder. Suddenly, something snapped, and she went limp. I was still on top of her, and when I removed the blanket I saw that she was dead. One terrible eye was still open, staring at me, and in that horrifying eye I could see everything I loathed about myself.

Bohumil Hrabal (1914–1997) was born in Moravia and started writing poems under the influence of French surrealism. In the early 1950s, he began to experiment with a stream-of-consciousness style, and eventually wrote such classics as Closely Watched Trains (made into an Academy Award-winning film directed by Jiri Menzel), The Death of Mr. Baltisberger, and Too Loud a Solitude. He fell to his death from the fifth floor of a Prague hospital, apparently trying to feed the pigeons.

Paul Wilson has translated books by Václav Havel, Bohumil Hrabal, Ivan Klima and Josef Škvorecký. He lives in Canada.

This excerpt from Memoirs of a Polar Bear is published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © 1965 by the Bohumil Hrabal Estate, Zurich, Switzerland. Copyright © 2019 by Paul Wilson.

Published on October 29, 2019.