When you enter the British Library in London and make your way up a short flight of stairs, you find a dark and somewhat mysterious space called the “Treasures Gallery.” This ongoing exhibition, described by Time Out as “the holy grail for history buffs,” displays “some of the world’s most exciting, beautiful and significant books and manuscripts” (“Sights for Sore Eyes” & “Treasures of the British Library”). Alongside national treasures such as the Magna Carta, Shakespeare’s First Folio, and drafts of the Beatles’ lyrics, the gallery includes European masterworks such as the Gutenberg Bible and Leonardo da Vinci’s notebook. The exhibit, which is free and open to the public, also displays stunning items from around the world, including a Chinese star chart, a seven-volume Qur’an from Cairo, and a copy of Audubon’s Birds of America (“British Library Treasures”).

The scope and framing of this collection raise a number of questions. How did these diverse “treasures” come to the UK? Why are these objects so valuable? And what does it mean that they are displayed in a “British” space?

To begin answering these questions, I offer a case study of one of the most beautiful items on display in the Treasures Galley: Harley MS 4431, commonly known as the Queen’s Manuscript. This luxurious book is described by the British Library as one of its “best-loved (and most-requested) medieval manuscripts” (Biggs 2013). Visitors who are unable to visit the Treasures Gallery or wish to explore the manuscript more fully can peruse the book through an online digital facsimile (“Harley MS 4431”).

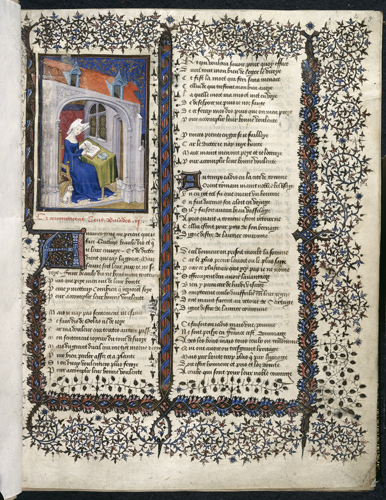

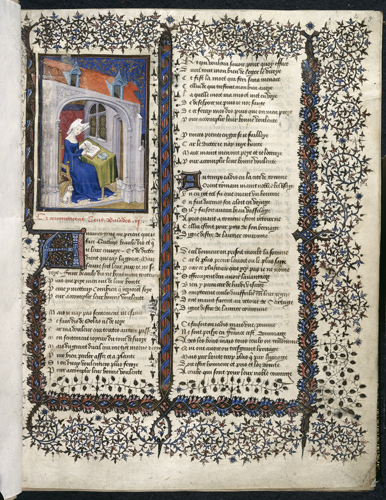

The Queen’s Manuscript is visually stunning—it includes over one hundred colorful illustrations highlighted with gold leaf, and features a complex program of winding scrolls and vines that frame the hand-written text. The textual contents of the book are also impressive—the book’s 398 folios (about 800 pages) present the diverse oeuvre of Christine de Pizan, a French writer active in Paris between 1394 and 1430 (“Harley MS 4431”). The collection contains love lyrics, narrative poems, political manuals, educational treatises, and proto-feminist texts. Christine’s authorial self-portrait can be found on folio 4r (“Harley MS 4431, folio 4r”).

The Queen’s Manuscript was framed as a prestige object at the moment of its creation and continues to command attention today. The book was produced under Christine de Pizan’s direct supervision in her manuscript workshop in Paris, and was presented as a New Year’s gift to Isabel of Bavaria, Queen of France in 1413 (Laidlaw 1987; Laidlaw 2006). This event is commemorated in a large illustration on the opening page of the manuscript. This image shows Isabel in a beautiful bedroom surrounded by a group of courtly women as Christine presents her with the book (“Harley MS 4431, folio 3r”). Christine de Pizan thus intended the lavish book to be treasured and displayed although she could not have anticipated that this resolutely French manuscript would become the centerpiece of a British collection.

The placement of the Queen’s Manuscript in the Treasures Gallery at the British Library prompts a number of questions. Why does the impulse to treasure and display books cross countries and centuries? How do international politics and national identity play into the acquisition, valuation, and display of cultural objects such as medieval manuscripts? What does it mean that a French manuscript is one of the “best-loved” books at the British Library? While the scope of this article bars a full consideration of these broad questions, an examination of the circumstances in which the Queen’s Manuscript and similar books reached England during the fifteenth-century demonstrates how literature and luxury objects structure cultural identity and illuminates our continuing desire to categorize medieval books as “treasures.”

Completed in Paris in 1413, the Queen’s Manuscript was transported to England as early as 1435. During the 1420s and 1430s, the English experienced a period of temporary success in the Hundred Years War, a long-standing dynastic conflict between England, France, and Burgundy over control of the French throne. Following a series of victories under King Henry V, many English aristocrats, commanders, and soldiers celebrated their position of ascendancy by seizing and purchasing French books and other valuable cultural objects. The acquisition of these books was a political statement designed to assert English control over both French lands and French culture (Catto 2011).

The epicenter of this transfer was the acquisition of the French Royal Library by John, Duke of Bedford, brother of Henry V and recently-named Regent of France. This large cache of books, termed in a later inventory “the grete librarie that cam owte of France,” was a repository of French intellectual and literary works, carefully curated by King Charles V of France to include French translations of the classics, French translations of the Bible, and the work of contemporary poets such as Guillaume de Machaut, Eustace Deschamps, Christine de Pizan, and Alain Chartier (Catto 2011; Stratford 1993). Bedford dispersed many of these French books to English commanders in his service, facilitating the movement of French texts across the Channel and expanding England’s perceived claim to French culture (Catto 2011; Stratford 1993). In addition to the main collection of books held at the Louvre, Bedford also acquired books from smaller royal collections held elsewhere in Paris, including the personal library of Isabel of Bavaria, Queen of France (Vallet, 1858; Adams 2010). It is from this smaller collection that Bedford likely acquired the Queen’s Manuscript.

At some point between 1433 and his death in 1435, Bedford gave the Queen’s Manuscript to his second wife, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, a noblewoman from the Burgundian Low Countries. Like the Queen’s Manuscript, Jacquetta had crossed the English Channel in the context of the Hundred Years War—her marriage to Bedford was intended tobolster the Anglo-Burgundian alliance against the French (Pascual 2011). As a deluxe book from Paris, the Queen’s Manuscript was a material symbol of wealth and legitimacy that Jacquetta may have used to preserve and advance her social and political standing in England after her husband’s death. She was likely aware of the French-royal provenance of the Queen’s Manuscript and the political meaning encoded in its passage to England. The book was a superb example of the artistic and literary French culture over which the English sought dominance. Jacquetta may have capitalized on this social and political symbolism by sharing the impressive French book at social gatherings or displaying it continuously on a lectern at her London residence.

Jacquetta also ensured that anyone who encountered the manuscript knew that this was her book. Like a modern reader asserting their ownership over a favorite book, Jacquetta registered her possession of the Queen’s Manuscript by personally writing her name “Jaquete” and her motto “sur tous autres” (above all others) on the front flyleaf of the manuscript. Jacquetta also inscribed her name in the margins of three additional pages of the manuscript and placed her motto at the base of a fourth page, further reinforcing her possession of the manuscript and leaving evidence of engaged reading (Watson 2017).

Jacquetta was not the only member of the English nobility to acquire and treasure a French book. John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury, Thomas, Lord Scales, and Sir John Fastolf, commanders who served in France under Jacquetta’s husband the Duke of Bedford, also curated collections of books from France. Sir John Fastolf’s collection bears a particularly close relationship to Jacquetta’s. Like Jacquetta, Fastolf acquired books from the French royal libraries through John, Duke of Bedford. Serving as the chief steward of Bedford’s household between 1422 and 1435, Fastolf acquired a substantial cache of continental French books (Harriss 2004). The specific manuscripts Bedford gave to Fastolf were not recorded, but a list of likely candidates can be surmised from a later inventory of Fastolf’s goods made in 1448. The inventory, found in a small booklet held at Magdalen College, Oxford, includes a detailed list of “Frenshe books,” including translations of Livy’s History of Rome, Vegetius’ De re militari, and Aristotle’s Ethics, all texts found in the inventories of the French royal library (Beadle 2008; Delisle 1907).

Like Jacquetta, Fastolf used French books to communicate his social standing and cultural prestige. In 1450, Fastolf commissioned a luxurious new copy of Christine de Pizan’s Epistre Othea, an allegorical treatise that takes the form of a verse letter written by Othea, the goddess of Prudence, to Hector, the young prince of Troy (Christine de Pizan 2017). Now Oxford, Bodleian Laud. Misc. 570, this lavish book was made using a continental copy of Christine’s text (“Oxford Bodleian Laud. Misc. 570”). Fastolf had his personal motto “Me Fault Faire” (I must act) incorporated throughout his new book (Driver 2009). While Jacquetta inserted her presence into the Queen’s Manuscript through marginal annotations, Fastolf went one step further, asserting his possession of French literary and artistic material by commissioning a new customized manuscript. Through this act of duplication and cultural appropriation, a “French” manuscript was re-made as an “English” manuscript.

As these examples demonstrate, deluxe manuscripts played a central role in articulating cultural identity and negotiating political ascendency during the fifteenth century. During the Hundred Years War, English aristocrats such as Bedford, Jacquetta, and Fastolf curated a hybrid Anglo-French identity, a posture that underwrote England’s political claim to France. This self-fashioning was achieved, in part, through the acquisition and circulation of luxurious French manuscripts. English aristocrats personalized, displayed, and gifted these valuable cultural objects, using them to build a cultural identity that reflected their successful military campaigns in France.

So, how does this history illuminate our understanding of how and why medieval manuscripts are displayed today? As we have seen, these literary and artistic masterworks are complex symbols of cultural identity. In the fifteenth century, the Queen’s Manuscript served as a material indicator of England’s nascent (and ultimately temporary) Anglo-French identity. In a similar vein, how might the display of the Queen’s Manuscript in the Treasures Gallery at the British Library speak to the construction of cultural identity in Britain today?

In the Treasures Gallery, the Queen’s Manuscript is displayed amidst an international collection that reflects Britain’s engagement with Europe and the wider world. Jane Austen’s juvenilia can be viewed alongside the musical score of Handel’s Messiah and a highly decorated Ethiopic Bible (“British Library Treasures”). In the same way that the Queen’s Manuscript enabled English aristocrats to perform an Anglo-French identity in the fifteenth century, the Treasures Gallery speaks to Britain’s past and current desire to style itself as culturally international.

The mission of the British Library mirrors the Treasure Gallery’s double focus on national history and international engagement. One the one hand, the BL describes itself as the “national library of the United Kingdom” and notes its aim to “build, curate and preserve the UK’s national collection of published, written and digital content” (“British Library – About Us”). At the same time, the BL is dedicated to international outreach and collaboration. The BL notes: “We work with partners around the world to advance knowledge and understanding…The British Library has a distinctive and important role to play alongside others in this global system, not least as our collection is perhaps the most international of its kind” (“British Library – About Us – International”). The British Library thus frames itself as a national entity that is actively engaged in an international cultural network.

The mission of the British Library, the composition of the Treasures Gallery, and the display of the Queen’s Manuscript illuminate how books can be used to negotiate the relationship between national and international identity. The dual construction of British identity as both insular and international owes much to a medieval history of European conquest, several centuries of global colonialism, and half a century of participation in international communities such as the European Union. The Treasures Gallery at the British Library presents this long history to a national and international public through a curated collection of books and other cultural artifacts. The objects on display have carried different meanings across time. Many items were acquired through conquest and served as symbols of political dominance. Today these items are reframed as examples of international exchange and collaboration. The Treasures Gallery invites visitors to “discover stories that shape the world,” cultivating an enthusiasm for geographically and temporarily diverse literary traditions and framing international engagement as central to the past, present, and future of Great Britain ( “Treasures of the British Library”).

Sarah Wilma Watson is a Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Haverford College. Her research examines the interrelation of gender, book history, and transnational literary culture.

References:

Adams, Tracy. The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2010.

Beadle, Richard. “Sir John Fastolf’s French Books.” Medieval Texts in Context. Ed. Graham D. Caie and Denis Renevey. London: Routledge, 2008. 96-112.

Biggs, Sarah J. “Christine de Pizan and the Book of the Queen.” Medieval Manuscripts Blog, The British Library. 27 June 2013. https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2013/06/christine-de-pizan-and-the-book-of-the-queen.html Accessed May 25 2019.

“British Library – About Us.” The British Library. Accessed May 25 2019. https://www.bl.uk/about-us

“British Library – About Us – International.” The British Library. Accessed May 25 2019. https://www.bl.uk/about-us/our-vision/international

“British Library Treasures – Collection Items.” The British Library. Accessed May 25 2019. https://www.bl.uk/british-library-treasures/collection-items

Catto, Jeremy. “After Arundel: The Closing or Opening of the English Mind?” After Arundel: Religious Writing in Fifteenth-Century England. Ed. Vincent Gillespie and Kantik Ghosh. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011. 43-54.

Christine de Pizan. Othea’s Letter to Hector. Trans. and Ed. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski and Earl Jeffrey Richards.Toronto: Iter Press, 2017.

Delisle, Léopold. Recherches sur la librairie de Charles V. Vol. 1-2. Paris: H. Champion, 1907.

Diaz Pascual, Lucia L. “Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Duchess of Bedford and Lady Rivers (c. 1416-1472).” The Ricardian 21 (2011): 67-91.

Driver, Martha W. “ ‘Me fault faire’: French Makers of Manuscripts for English Patrons.” Language and Culture in Medieval Britain:The French of England, c. 1100-c1500.Ed. Jocelyn Wogan-Browne. York, UK: York Medieval Press, 2009. 420-43.

“Harley MS 4431.” British Library Catalog of Digitised Manuscripts. Accessed May 25 2019. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Harley_MS_4431

“Harley MS 4431, folio 4r.” British Library Catalog of Illuminated Manuscripts.

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMINBig.ASP?size=big&IllID=28574

“Harley MS 4431, folio 3r.” British Library Catalog of Illuminated Manuscripts.

https://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts/ILLUMINBig.ASP?size=big&IllID=35552

Harriss, G.L. “Fastolf, Sir John(1380–1459).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. Online edn, Jan 2008. Accessed 16 Aug 2017. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9199

Laidlaw, James C. “Christine de Pizan: A Publisher’s Progress.” The Modern Language Review82.1 (1987): 35-75.

______. “Christine de Pizan: the Making of the Queen’s Manuscript (London, British Library, Harley 4431).” Patrons, Authors and Workshops: Books and Book Production in Paris around 1400. Ed. Godfried Croenen. Leuven: Peeters, 2006. 297-310.

“Oxford Bodleian Laud. Misc. 570.” The Digital Bodleian. Accessed May 25 2019.https://iiif.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/iiif/viewer/9fac8874-7559-4dca-a772-70556ade8146#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&r=0&xywh=-3289%2C-232%2C9337%2C4618

“Sights for Sore Eyes: Alternative Places to Visit in London.” Time Out: London. July 17 2018. https://www.timeout.com/london/things-to-do/sights-for-sore-eyes-alternative-places-to-visit-in-london

Stratford, Jenny. The Bedford Inventories: The Worldly Goods of John, Duke of Bedford, Regent of France (1389-1435). Vol. 49. London: Society of antiquaries of London, 1993.

“Treasures of the British Library.” The British Library. Accessed May 25 2019. https://www.bl.uk/events/treasures-of-the-british-library

Vallet de Vivirille, Auguste. La Bibliotheque d’Isabeau de Bavière, femme de Charles VI, roi de France. Paris: J. Techener, Libraire, 1858.

Watson, Sarah Wilma. “Jacquetta of Luxembourg: A Female Reader of Christine de Pizan in England.” Women’s Literary Culture and the Medieval Canon. University of Surrey. February 27, 2017. https://blogs.surrey.ac.uk/medievalwomen/2017/02/27/jacquetta-of-luxembourg-a-female-reader-of-christine-de-pizan-in-england/

Acknowledgements:

Sarah Wilma Watson would like to thank Daniel Davies and Erika Harman for reading a draft of this piece and offering numerous helpful suggestions. She would also like to thank Dr. Eleanor Jackson at the British Library for sending her information about the current display of the Queen’s Manuscript.

Photo: The Queen’s Manuscript –British Library MS Harley 4431, f. 4r. Copyright ©British Library Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts.

Published on September 10, 2019.