This is part of our special feature, Digitization of Memory and Politics in Eastern Europe.

A spotlight on the University of Helsinki.

The Digital Humanities Module at the University of Helsinki is aimed at the MA level and is open to all students at the university. The main learning objective is to help students find a common language among the humanities, the social sciences, and data science. In the long term, this will enable the renewal of a scholarly culture and also prepare students to work as professionals outside academia.

Humanities in Nokia-Land

The overwhelming impact of digitization is hard to deny (especially if you live in the promised land of Angry Birds and Nokia). From teachers at elementary schools to university professors, humanists and social scientists are facing increasing demands related to the use of new applications, methodologies, modes of collaboration, and big data. Simultaneously, university curricula are under pressure to evolve. Amidst all the fuzz about the digital, it is essential to respect the fact that the value of social science and humanities (SSH) research is based upon a critical understanding of human nature, communities, cultures and their interaction, and is thus not dependent on particular technologies or what they enable. Nevertheless, there is no reason to rely on outdated methodologies in developing this critical understanding.

Changing the way core humanities subjects, such as history and cultural studies, are taught is a daunting task. Although there is nothing particularly problematic in teaching programming skills to a humanist who is willing to learn, tying this capacity to actual practice—and renewing how research is conducted—is a challenge. There is also the worry of an emerging scholarly gap between core experts in humanities and those who experiment with new methods on humanities data without producing plausible results from the perspective of the experts in the traditional fields.[1] Research practices in the humanities have developed over centuries, in contrast to the revolution in digital methods that is happening at breakneck speed. New methods are definitely out there, but it may be very difficult to change best practices (and age-old habits) in a particular SSH field. The problem has much to do with funding and staffing. Stanford University aside, at most universities, if a department hires people with computational background, that means that some other type of expertise might be compromised. Digital humanities easily becomes a heated political issue. At the same time, there are justified worries about how new competences are acquired. What, then, should be done?

If we wish to change the practice of, say, historians, we need to tailor their capacities-to-be-acquired to their own interests. Why would they engage in anything if it does not help them in real work? The field of digital humanities (DH) is not a new invention. There have been programming historians in Finland and elsewhere for decades, but still the effects of digital humanities on the working practices of the average historian have been slight or non-existent. The problem is not that most historians have not bothered to learn how to code: there just has not been the need for it. New skills can become part of any profession only when programming ability, for example, produces results that would not otherwise have been achievable. However, with the increasing digitization of our cultural heritage, we are reaching a tipping point. The tide is slowly starting to turn. Why would you not use machine learning to research digitized manuscript material if you have the opportunity to do so? Why would you not apply the ability for critical thinking that a humanist generalist degree provides to face the challenges of the digital world? It would probably secure you a decent job, to say the least. What is more, because of your ability to think differently from all those engineers out there in a company, who knows where you might end up after making a couple of positive contributions? All of a sudden there are good reasons to be (or to become) a programming historian or a digital humanist if you think about the future.

However, judging from where most SSH departments still stand today, the practice of historians, for example, has not yet been transformed, which at the same time makes it challenging to change the way future historians are trained. Given the impact of teaching on research, we are facing a chicken-and-egg stalemate. Conservative professors tend to produce conservative disciples. What we need are significant research results based upon new methods that impact the core research fields. Archaeology is a good example of a field in which particular methods borrowed mainly from the life sciences have changed the way the past is being modelled. Journal articles published in the best traditional forums using new methods should accelerate the transformation in more conventional SSH fields. If we can show that computational methods yield results that are otherwise impossible to show, the scholarly culture will change. Once this happens, the momentum with respect to teaching will also gather pace. People in universities are generally clever enough to do what is necessary to stay in the game. Sometimes this might mean resisting change until you are happily retired, but not everyone is a cynic. For younger practitioners it often means learning new tricks, or to use a more appropriate expression, revising scholarship. It is this change in the scholarly culture that is the greatest obstacle to the digital transformation of the humanities and social sciences. It takes time and it needs a lot more than a few encouraging yet esoteric blog posts or tweets about what can be done with big data.

At the same time, if we are correct in predicting that this digital transformation will eventually happen and that core subjects in the humanities will be renewed, there is no reason not to try and accelerate the process through teaching, not least for the sake of being able to compete on the international level. For this reason, on the incentive of now-retired Dean Arto Mustajoki (https://375humanistia.helsinki.fi/en/humanists/arto-mustajoki) and current Vice-Rector Hanna Snellman (https://375humanistia.helsinki.fi/en/humanists/hanna-snellman), in 2015 I was given free hands to design a Digital Humanities module at the University of Helsinki (on condition that it would be implemented within three months…).

Integrated Multidisciplinarity in the Humanities

My vision, ever since I was a doctoral student, has been to promote cross-disciplinary collaboration in the humanities, meaning that digital humanities is not only about training programming historians and that we should move towards a model that works in the life sciences in bringing different types of expertise together and creating a division of labor based on mutual language. This collaboration cannot mean taking on data or computer scientists merely to conduct particular computational tasks, however. The process of revising the culture of humanities research must be based on integration. The magic word in computational humanities and social science should not be “digital,” it should be “integrated.” This will not be easily accomplished, but it should be our goal. When I was designing the Digital Humanities module, I had already embarked on a twin-collaboration project on historical metadata with data scientist Leo Lahti, associate professor in data science and computational humanities in University of Turku, Finland. This helped considerably when the Faculty of Arts recruited computer scientist Eetu Mäkelä (who is currently an assistant professor of human sciences-computing interaction) to help me set up the Digital Humanities program. All of this happened some time before the Helsinki Centre for Digital Humanities (HELDIG) was founded. This chronological context is important because it means that from the very beginning the idea of digital humanities at the Faculty of Arts has been based on cross-disciplinary collaboration at all levels. Since the establishment of HELDIG we have also received crucial help from HELDIG’s coordinating researcher Jouni Tuominen in the organization and coordination of the teaching.

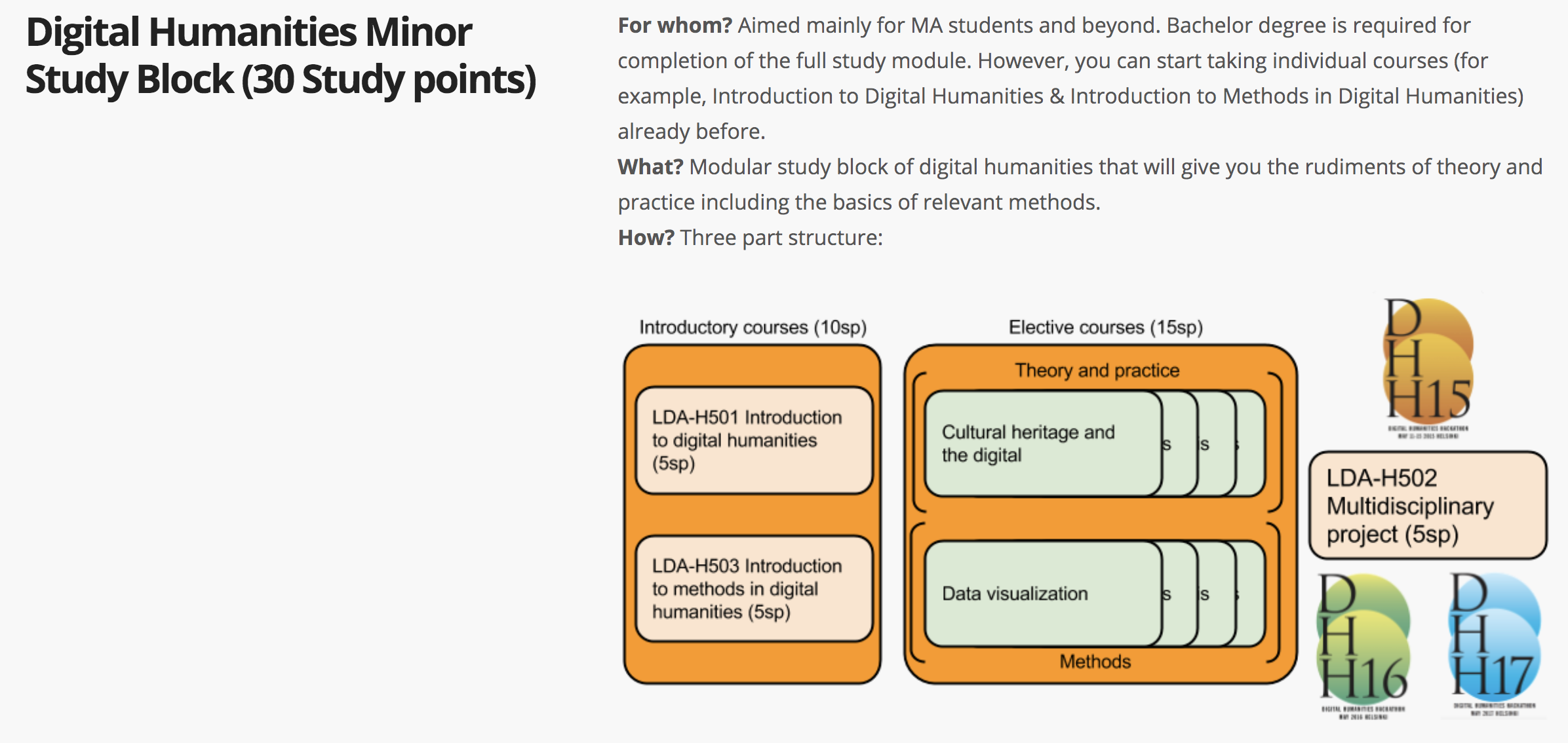

Figure 1. Overview of Digital Humanities Minor Study Block

The first established step in teaching digital humanities at the University of Helsinki was the implementation of a modular minor-subject study block of 30 ECTS credits that could be connected to any MA degree. DH teaching is meant to cater to a varied pool of interests. Hence, the teaching has been designed to include different tracks in the program. There are two mandatory introduction courses that everyone needs to take (general introduction and methods). After this, students are free to elect their own desired courses with an emphasis on either “Theory and practice” or “Methods.” This also allows for a more specific focus on digital culture.

There are many crucial aspects of the digital world in current society in which humanists should be more involved, such as big data, my data, smart cities, the platform and circular economy, and the use of neural networks. A lot of critical thinking should be employed when determining how modern cities are evolving in the light of different digital developments, for example. Converserly, current smart city projects in different parts of the world would definitely benefit from a stronger humanities impact. Questions concerning how to preserve and how to use our cultural heritage in digital form should be part of the ethical training of every SSH student. We should be much better in the arts and humanities at identifying these different current trends as they evolve.

Digital Humanities Minor Study Block (30 ECTS Credits)

For whom? The study block is aimed mainly at MA students and beyond. A Bachelor’s degree is required for completion of the full study module. However, it is possible to take individual courses (for example, Introduction to Digital Humanities & Introduction to Methods in Digital Humanities) beforehand.

What? This modular digital humanities study block gives students the rudiments of theory and practice, including the basics of relevant methods.

How? The curriculum follows a three-part structure. The two mandatory introductory courses of the module are taught each autumn:

- LDA-H501 Introduction to digital humanities (5sp)

- LDA-H503 Introduction to methods for digital humanities (5sp)

After taking those courses, students are free to choose 15sp worth of elective courses from the Theory and practice and Methods selections (10sp if they are already enrolled in an earlier version of this module). The module closes with the LDA-H502 Multidisciplinary project (5sp) that takes place each spring in a hackathon spirit where students work intensively for 8-10 days straight (from morning till evening, and sometimes even during the night, to be able to produce an academic poster and presentation of the group’s work in a public event before the champagne bottles are opened).

The DHH Concept: Helsinki Digital Humanities Hackathon

What is unique about the DH minor at the University of Helsinki—and something of which I am particularly proud—is that the introductory and elective courses have a specific aim: students are able to put their skills and abstract knowledge into practice at the end of each academic year in a multidisciplinary research project entitled Helsinki Digital Humanities Hackathon. Thus, they are acquiring skills that will be useful to them regardless of whether they are thinking about an academic career or aiming to find a job outside academia. Project participants are also able to do real digital humanities work with students and academics from multiple different backgrounds.

The Digital Humanities Hackathon (DHH) is designed for students in the fields of computer science, humanities and social science interested in working on big data, artificial intelligence and machine learning in a humanities framework. The course is also offered separately as part of the data science MA program and at Aalto University for students of computer science. Recruiting data scientists and computer scientists who are interested in SSH research is a key to success in this kind of multidisciplinary endeavor.

The core idea (as in our general vision of where the use of computational methods in SSH research should be taking us) is to apply data science to research questions in the social sciences and humanities. The hackathon gives students of data science the opportunity to apply their knowledge acquired at the university to real-life problems; it also gives SSH students the opportunity to pose research questions on big data and to solve them by means of machine learning and artificial intelligence.

During the hackathon, each group develops a digital humanities research project from start to finish. Working together, they formulate research questions with respect to particular data sets, develop and apply the methods and tools that will answer them, and present their work at the end of the project. The participants learn how to work in multidisciplinary research projects. They also broaden their understanding of digital humanities, and of what it is possible to achieve through such collaboration.

Everything in Digital Humanities in Helsinki is geared towards multidisciplinary collaboration. Our hackathon also functions as an international summer school for CLARIN-EU, European Research Infrastructure for Language Resources and Technology, that supports cutting edge data-driven research at Europe-wide level and DARIAH-EU, Digital Research Infrastructure for the Arts and Humanities, that aims to enhance and support digitally-enabled research and teaching across the arts and humanities. Our hackathon thus offers an international experience for our students and for outside participants. The feedback on DHH we have received over the years has been overwhelmingly positive.

#DHH19, the 2019 version of Helsinki Digital Humanities Hackathon, gathered students and researchers in the fields of humanities, the social sciences and computer science at the University of Helsinki in May 2019. During a week and a half of intensive multi-disciplinary work, the groups applied digital methods to a variety of datasets, with the goal of solving research questions on the following themes:

- The Many Voices of European Parliamentary Debates

- Genre and Style in Early Modern Publications

- Brexit in Transnational Social Media

- Newspapers and Capitalism

In addition to offering the teaching module, we aim to provide learning opportunities to researchers in humanities and the social sciences, as well as to anyone willing to study digital humanities independently. To serve these audiences, we run a Digital Humanities Research Seminar and we have multiple online learning materials in active development.

Future Developments

Currently, we are in the process of expanding the 30-credit minor-subject study module to a full-size MA track in Digital Humanities by 2020. The idea is also to move towards offering a select group of MA students the opportunity to integrate into relevant research groups at the University. The teaching is divided between mandatory and elective courses, and project courses organized specifically with this integration of students into research in mind. We will also engage in closer collaboration with different disciplines in the design of specific courses to enhance the overhauling of subject matter and the development of new methods and theoretical approaches. We do not intend to forget training for life outside academia, either. In the future, we will work even more closely with employers in the designing of particular courses. One potential and valued profession that is open to humanities students is that of an upper-secondary school teacher. Closer collaboration with schools, cities and the Ministry of Education and Culture is needed to meet the changing needs in the teaching of humanities in upper-secondary schools. Thus, the profile that we aim for in our MA track in digital humanities serves two general objectives: 1) renewing the scholarly culture in particular areas of the humanities through the introduction of innovative methods in history, for example; 2) meeting the challenge of digitization in the training of humanities professionals to maintain their core ability for critical reflection in the digital world, and at the same time to participate in multidisciplinary collaboration with professionals of different backgrounds.

A crucial concept in the philosophy of teaching digital humanities at the University of Helsinki is that of open science. As humanists, we should be able to tackle difficult questions such as reusability in science, the relevance of equality, and the essence of democratic practices in society, as well as the renewal of the scholarly culture. A further aim is to challenge the border between the quantitative and the qualitative. The STEM disciplines (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) need SSH research as much as Humanities need them. Without a society-wide hermeneutic understanding of the world, we will soon start slipping towards a dystopia in which democratic principles are undermined. That is just one reason why we need integrated digital humanities.

For a short introductory video of the module aimed at prospective students at the University of Helsinki, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QNTFoqLfKRE

For a video introducing the Helsinki Digital Humanities Hackathon, see: https://youtu.be/CX-ZhLYmLa0

Mikko Tolonen (PhD in history from the University of Helsinki) is a researcher with a background in history of philosophy and intellectual history who has spent a large slice of his life considering if, why and how private vices lead to public benefits. In his post-doc years Tolonen awakened to the full potential of modern data processing techniques in historical research. Currently, he is Assistant Professor and subject head of digital humanities at the Department of Digital Humanities at the University of Helsinki and the leader of the Helsinki Computational History Group (COMHIS). In 2015-17 he worked also in the National Library of Finland and its project on digitized newspapers as professor of research on digital resources. He is the chair of Digital Humanities in the Nordic Countries (DHN) and member of the executive board of the European Association for Digital Humanities (EADH). His current main research focus is on an integrated study of early modern public discourse and knowledge production that combines metadata from library catalogues as well as full-text libraries of books, newspapers and periodicals. In 2016, together with his research group, he was awarded an Open Science and Research Award by the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture.

[1] For a debate about the value of computational methods in a traditional humanities field, cf. Nan Z. Da, “The Computational Case against Computational Literary Studies,” Critical Inquiry 45, no. 3 (Spring 2019): 601-639 and https://critinq.wordpress.com/2019/04/12/more-responses-to-the-computational-case-against-computational-literary-studies/.

Photo: Abstract tech background | Shutterstock

Published on September 10, 2019.