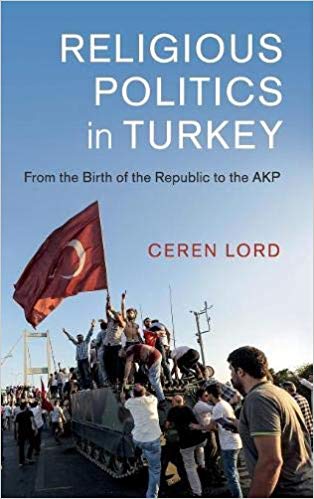

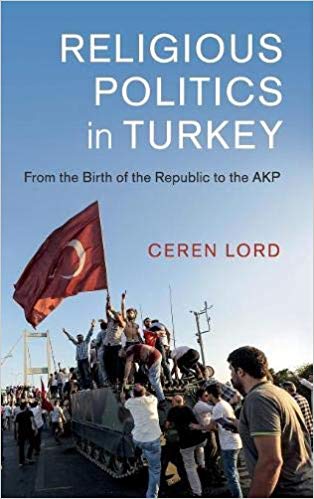

Once regarded as the poster child of Islam’s compatibility with democracy, Turkey is now drawing attention to itself for different reasons. The country’s rapid and unexpected authoritarian turn in recent years has unsettled many observers both at home and abroad. Turkey’s nearly century-old “Kemalist Republic” has been declared dead in the wake of the April 2017 constitutional referendum. With that death, so the argument goes, the potential for a “secular” Turkey has also faded. The conventional wisdom holds that these developments reflect the triumph of the so-called “religious masses” over an authoritarian secularist state. Religious Politics in Turkey: From the Birth of the Republic to the AKP takes issue with this essentializing narrative, contending that it assumes an unchanging reality and monolithic institutions. The book instead casts a light on the enduring contestation within the state over the meaning and place of religion in the Turkish Republic since its foundation in 1923.

Analytically sophisticated and empirically rich, Religious Politics in Turkey is a welcome contribution to a growing corpus of critical scholarship on secularism and secularization in Turkey. Going beyond the rather tired “center–periphery” paradigm and the standard narrative that the authoritarian secularist state co-opted Islamists, Ceren Lord focuses on actors and their choices at critical junctures. “Integration of Islamic authority” into the government through the Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet), she argues, “embedded a religious majoritarian logic within the state” that persisted over time (124). The expansion of religion into the realms of economy, education, and welfare provision under the influence of Cold War politics and neoliberal restructuring of economy in the 1980s further advanced the institutionalization of Sunni Muslim Turkish supremacy. The increasing salience and visibility of religious politics under the current AKP government is thus cast—quite rightly—as a continuation of a long-standing pattern of Islamization (of state and society) in Turkey.

The chief merit of Lord’s argumentis its careful avoidance of determinism. She takes contingency seriously in explaining the inception and expansion of religious politics after 1923, against the backdrop of a growing struggle among various actors over ownership of the state apparatus. In developing her argument, Lord rightly foregrounds the persistence of Ottoman institutions and categorizations in shaping the republican state. In particular, she stresses antecedent conditions like the “intertwined nature of religious institutions and the state” and the strengthening of socio-religious boundaries (46), particularly in the context of the institutional, political, and social changes during the long nineteenth century.

Confronted in the late eighteenth century with European incursions—alongside territorial losses and increasing ethnicization of confessional identity across the empire—imperial elites responded with a series of reforms. These, it was thought, would solve the growing challenges in governing ethno-religious diversity and the organizational crisis within the state. However, they were not unique to the Ottoman Empire. Instead, they were part of a worldwide interest in refashioning the contoursof legitimate statehood, particularly through constitutionalism and legal codification. This period also marks the beginning of a battle within the state apparatus over the place of religion within the political order. The Ottoman loss in World War I, and the subsequent independence war against Allied Forces led by Mustafa Kemal (later Atatürk), catalyzed a broad coalition of factions within the state, despite their opposing views regarding the proper scope of state–religion relations. Faced with a choice between two competing global socio-political projects in the aftermath of the World War I, the founders of the Turkish Republic plumped for the Wilsonian principle of nationalist self-determination over the anti-imperialist internationalism of the Bolshevik Revolution.

Lord hits the nail on the head when she asserts that “the emergence of laicism had been reflective of a power struggle within the state, which involved the elevation of one faction of the independence struggle coalition over others” (53). Signed in July 1923, the Lausanne Treaty between the representatives of Ankara government and the Allied Forces became the founding document of the Turkish Republic. By signing, Turkey was finally admitted as a full member of the league of Westphalian sovereign states premised on the congruence between territory, sovereignty, and population. The very principle of religious majoritarianism was thus as much due to the Ottoman legacies as it was a product of contemporary global trends—a point that is largely bypassed in the book’s main argument even if it is hinted in the empirical discussion.

As the Lausanne Treaty went into effect, the non-Muslim subjects of the Ottoman Empire became the minority citizens of the Turkish Republic. Religious difference in the republic defined the majority–minority distinctionas the new conceptualization, rather than continuation, of inter-ethnic and political relations. At the same time, religious difference became inconsequential in the governance of family law as a unified secular civil law was passed in 1926. This was, however, not because of a promise, as Lord notes (56), that the Turkish delegation gave during the Lausanne negotiations. After heated discussions, Article 42 of the Treaty stipulated a return to the organizational structure that was in place before the enactment of the 1917 Ottoman Law of Family Rights, which had significantly limited the non-Muslim millets’ legal autonomy. Even though the Turkish delegation opposed the suggestion—they asserted that pre-1917 pluralism in family law would produce a “state within a state” and that the new Turkish state would in any case enact a secular civil law ensuring equal treatment of its citizens regardless of religious affiliation—the final version of Article 42 left family matters to the jurisdiction of religious law without institutionalizing a deadline for the enactment of a secular code (Adar, 2019). Legislation of the 1926 secular civil law only became possible after the non-Muslim communities were convinced to renounce their right to Article 42 in 1925.

A radical secularization program was rolled out after 1925. The primary aim, as Lord points out, was to strip the ulema (but also non-Muslim religious authorities) of their power in order to consolidate the secularists’ position within the state. The program also sought, however, to weaken the salience of religious justifications in everyday social sphere as well as in the domestic sphere—a point that does not receive much attention in the book. For instance, the adoption during the Lausanne negotiations over Article 42 of wording that drew a clear distinction between “secular” and “religious”—had not existed before the collapse of the empire. Such secular understanding of social and domestic life was different from, and in fact, at odds with an ethno-religious understanding of nationhood (what Lord identifies as “religious majoritarianism”) that was shared by a broad coalition of actors. The foundational paradox that arose from these two competing understandings of religious difference left the state apparatus in the following decades open simultaneously to contestation and consensus (Adar, 2019).

The increasing Islamization of state and society in the post-1946 era emerged from the tensions of this foundational paradox, rather than merely from the tradition of “religious majoritarianism.” The outcome might have been different, however, if not for the catalyzing effects of various factors over time. Lord particularly draws attention to the contingent effects of political liberalization, Cold War geopolitical concerns, and a neoliberal restructuring of the economy in 1980s. Equally important but relatively underdeveloped are two other factors. The first is an increasingly prominent Kurdish-Turkish conflict starting in the 1970s and culminating in the eruption of a violent conflict in the 1990s between the Kurdish guerrilla and the Turkish army. The second is the eruption of the Arab Spring in 2011 and the subsequent de facto disintegration of Saudi Arabia’s decades-long coalition with Sunni Islamists through the Muslim World League initiative.

Policies are never neutral with respect to politics, which invariably shape and are shaped by alliances and cleavages among actors. What happens at any key historical moment is not inevitable. It is instead an outcome contingent on historical processes and actors’ decisions. Lord’s book is a valuable contribution in this respect. A captivating book and a welcome addition to a growing genre of critical scholarship on secularism in Turkey, Religious Politics in Turkey would nevertheless have benefited from a discussion over what other paths might have been taken in the long and contested process of state formation, consolidation, and perhaps now even disintegration. What would have happened if Turkey had transitioned to multiparty elections later (or sooner)? How would history have unfolded had political actors responded differently to the Kurdish–Turkish conflict? Where would be we had the Arab Spring not erupted or ended differently? Questions that interrogate and historicize the trajectory leading to our current conjuncture are better able to shed light on the present predicament than hand-wringing over the demise of a romanticized and much overstated secular past.

Sinem Adar is currently an Einstein Fellow at Humboldt University of Berlin. As a comparative historical sociologist, Dr. Adar’s research focuses on mechanisms of inclusion and exclusion in religiously diverse societies, and their implications for identification processes. Her academic publications have appeared at Sociological Forum, Political Power and Social Theory, The History of the Family, and peer-reviewed edited volumes. She is also a supporter of public sociology, and occasionally writes for broader audiences in online magazines such as Jadaliyya, Open Democracy, ResetDoc, Muftah and Al Jazeera.

Religious Politics in Turkey: From the Birth of the Republic to the AKP

By Ceren Lord

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

Hardcover / 363 pages / 2018

ISBN: 9781108472005

To read more book reviews click here.

Published on September 10, 2019.

References

Adar, Sinem. 2019. “Religious Difference, Nationhood and Citizenship in Turkey: Public Reactions to an Interreligious Marriage in 1962.” The History of the Family. Accessible at the link: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1081602X.2019.1633380.