Different and Related: Experiences from the Project “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure (FoKO)”

This is part of our special feature, Digitization of Memory and Politics in Eastern Europe.

In the Schröder-Archiv part of the Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte – Bildarchiv Foto Marburg collection, there is a photo of the Church of Saint Ignatius of Loyola in Esztergom in Hungary with the destroyed bridge in the background[1] (Il.1).

The Mária Valéria bridge joins Esztergom in Hungary and Štúrovo in Slovakia, across the River Danube. Since its opening in 1895, the bridge has been destroyed twice, in 1919 and 1944. Decades of intransigence between the Communist governments of Hungary and Czechoslovakia mean that the bridge was not rebuilt until the new millennium. Since reopening in 2001, it serves as a border crossing-point to Slovakia. This story makes this photograph taken in 1985 a symbol of the political, social, and cultural relationships between the two states of Central Europe. The described photo can be seen in the “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure (FoKO),” which was finished and published online this year.[2]

The infrastructure exemplifies introducing methods and tools of digital humanities to the art-historical problems in the multilingual and culturally diverse milieu, but has also built bridges in the region—literally and figuratively—in the real and digital world. This international collaborative research project focuses on the particular achievements of artistic production in East-Central Europe: works of art, architecture, and cultural heritage regarded as highly significant. The transnational cataloged data and images were integrated to present multiple interrelations of artistic developments in East-Central Europe between 1000 and 1800, while also taking into account different national cultures of knowledge, which had been competing for dominance in interpreting matters of history and culture over a long period. It combines cataloging of historical image holdings and the creation of new standardized image material from nine countries (Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Romania). The project was based on the cooperation of three German institutions. Two of them deal with the East-Central European History: the Herder-Institute for Historical Research on East-Central Europe – Institute of the Leibniz Association and the Leibnitz Institute for Historical research an East-Central Europe (GWZO) in Leipzig. The specialists from the Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte – Bildarchiv Foto Marburg – Bildarchiv Foto Marburg agreed to share their knowledge about the practical challenges of indexing of image collections. The partners in the region were: the Polish, Slovakian, and Hungarian academies of sciences and humanities in Warsaw, Bratislava, and Budapest, the Rundale Palace Museum in Latvia, and the Lithuanian Culture Research Institute in Vilnius.

This kind of project is characterized by a juggling between specialist academic cooperation for the common good, protection, and promotion of the shared, human heritage, and politicization of both of the analyzed content, as well as practical activities and motivations of the project partners.

Based on the interpretation and negotiation of the concept of Central and East-Central Europe, there was a discrepancy in understanding between partners. What is more, the framework of a cultural center and its peripheries, together with interpretations of Central Europe based on the sociological context of patrons and commissioners’ networks have been present in the discussion and seem to reflect the balance of power in the region.

The international transfer of knowledge has been accelerated digitally, but it does take place in divergent academic and cultural milieus that are influenced by country-specific political, social, and economic factors, and continue to differ in communication strategies and technical facilities. Even the agreement of all project partners on a canon of objects became a long process because of the factors mentioned above. The final choice is the result of various traditions and political will represented by the institutions as well as the individual interests of researchers participating in the project.

The changing borders and different national cultures of knowledge are especially difficult to organize in the digital environment, which requires absolute precision in classifying of phenomena, defining geographical affiliation or the vocabulary used. Different interpretations, presentations of diverse points of view—or the scientific discourse, to be short—are reduced to the structured data. However, such a common platform becomes an excellent tool for data mining, combination, and finding structural links and interfaces. The FoKO database is a semantic database, which means the use of triples (subject-predicate-object). It is an additional challenge because it requires great precision in the content. It proves to be a daunting task for a historian working mainly with free text and fluid categories that cannot be easily categorized. The transformation of narrative descriptions into structured data is always an act of interpretation and selection. The implemented thesauri (the Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus, the German Integrated Authority File and the Polish Thesaurus for Cultural Heritage) were indeed very useful sources for controlled terminology, but they do not cover the complexity of the “peripheral” region. Some important East-Central European geographical and personal names are not included, or they require verification. There are no appropriate terms for some important artistic phenomena.[3] However, there are no similar controlled vocabularies in local languages. The Polish Thesaurus for Cultural Heritage is an exception here, but its scope is incomparable to the Getty AAT.[4] If we consider, that the controlled external vocabularies would allow integrating the local data into a broader network and so would the data become searchable, we have to postulate urgently the construction of authority files in local languages, as well as the mapping of them on the international standards. This requires not only the interest of researchers but also the political will that would sanction institutionally such projects.[5]

The juxtaposition of the image material indexed in the “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure” can also serve as a starting point for the analysis of the art monuments in their political contexts. The state of the preservation of the objects often reflects its political importance in the certain period of time. The communization of the cultural heritage after the WWII led to the dramatic dispossessions and the radical change of functions of many buildings. After 1989, in some circumstances, it became possible to regain monuments by the original owners who lost their right to them. In other cases, new private owners bought the architectural monuments. The privatization of cultural heritage has been associated with various types of problems, but there are many positive examples of successful revitalization, especially when institutions or associations became proprietors or administrators. Revitalization is, of course, a very complex problem at the interface between economic and political issues. The political contexts themselves are very diverse, depending on the type of the revitalized objects, for example, urban complexes, buildings regaining their sacred function or monuments in specific areas.

The process of revitalization is influenced both by the complexity of the monuments’ past as well as its political interpretation. It can be observed in the history of Środa Śląska—a Silesian town situated at the main transport routes joining the East and West Europe. Henryk the Bearded, whose idea was to enhance the economic and political significance of the Silesia region in order to unify the Polish Kingdom, carried out its transformation from a small commercial settlement into a center of urban character. Around 1235, he granted the settlement a special law, based on the Magdeburg law, but adapted to the local conditions (Prawo Średzkie). It was a model on which many other Polish towns were later founded. The town itself is also an excellent example of the challenging geographic affiliations. As part of Silesia, the town became a possession of the Habsburg monarchy in 1526; it was incorporated into the Prussian Kingdom in 1740, and it became a part of Poland in 1945.[6] In FoKO-infrastructure we can find the photographs of this town made shortly after 1950 as well as shots from 2018 (Il. 2).

The author of the oldest photos is the Polish photographer Stefan Arczyński. He was born in 1916 in Essen (Germany) and settled after World War II in Wrocław—a city newly connected to Poland. He documented the reconstruction of Poland, especially the so-called “Recovered Territories.” His photos of Silesian towns embody the history of not always straightforward relations between Poland and Germany. On the contrary, the newest pictures of Środa Śląska by Wolfgang Schekanski show colorful, restored facades of houses in the town regaining its splendor at the intersection of European routes.[7]

After the war, many sacral objects shared a certain fate. While in the western territories of Poland, the abandoned evangelical churches were destroyed, in the area of the Soviet Union the church estates were used by the authorities for secular purposes with full premeditation. The photographs in the FoKO-infrastructure document this process.

The Church of Our Lord in Antakalnis in Vilnius, here in the shots of Piotr Jamski[8] (Il. 3), was built 1696-1712, and between 1945-1992 it was used as a military camp. The three photos of the Church of the Holy Trinity built 1729 in Vowchyn (Il. 4-6), a village in Belarus, depict the fate of the object in different political constellations, from glorious times, through destruction to reconstruction.[9] The originals of all these photos are administrated by the Polish Academy of Sciences, which has a long tradition in documenting cultural heritage in the area of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

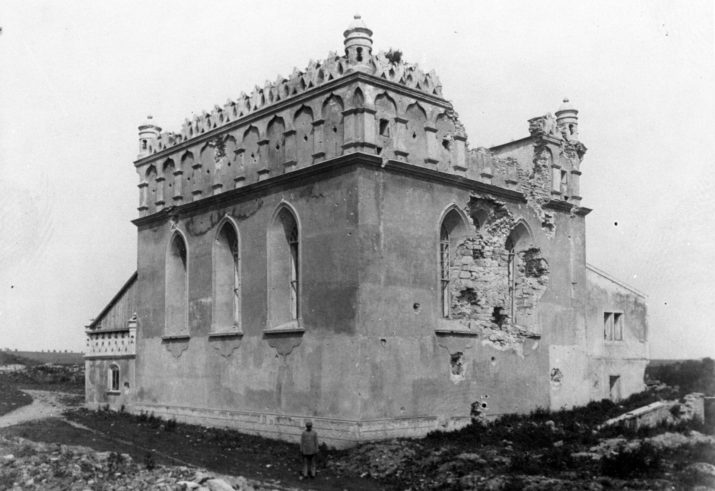

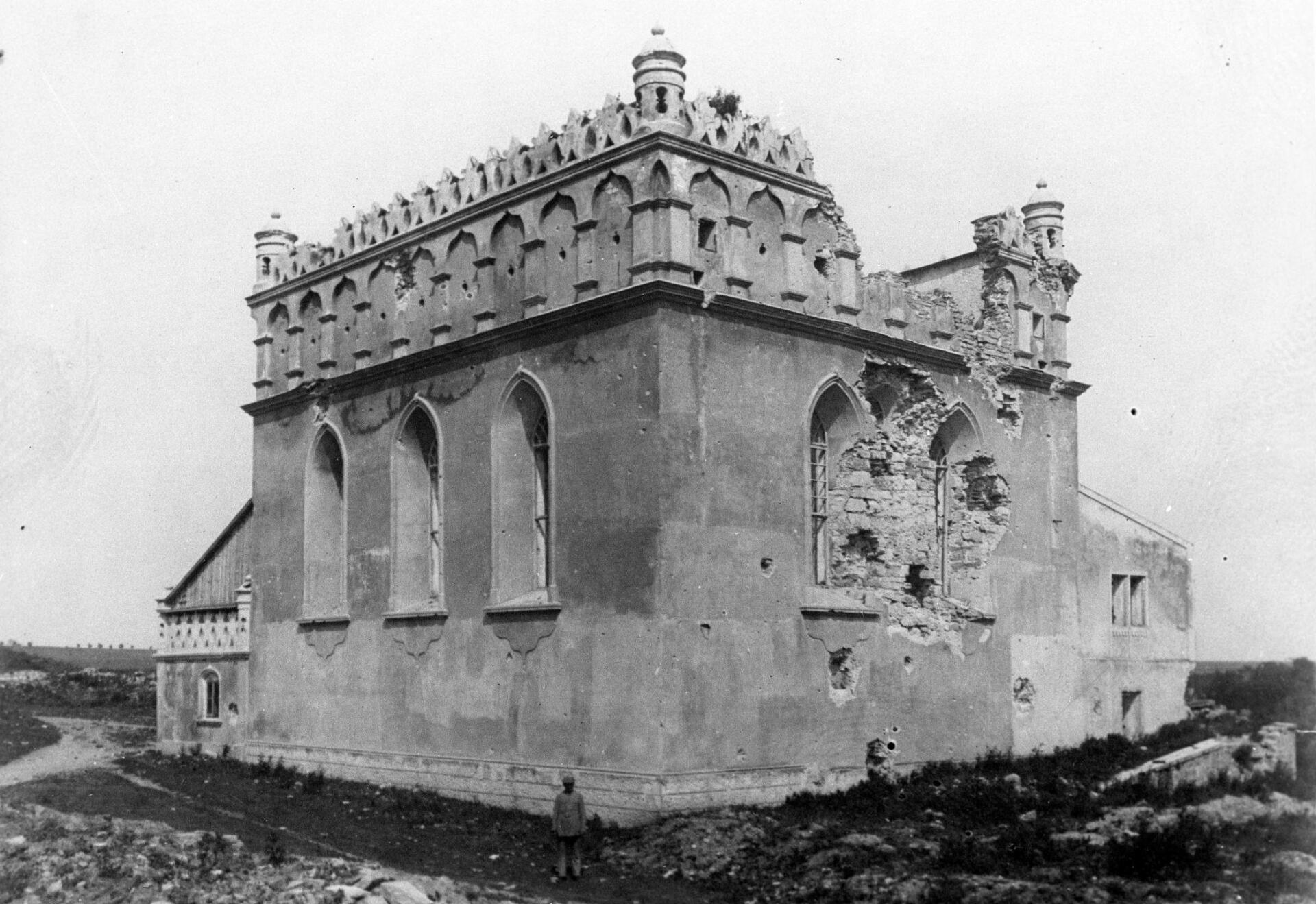

Also, German heritage in the East has been slowly regained (Il. 7). One example is Jeglava (Mitau) in Latvia and its palace that was built 1738-1772 by Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli for Ernst Johann von Biron. It was destroyed not only in 1944, but also during the French invasion of Russia in 1812 and during the February Revolution in 1917.[10] Furthermore, the infrastructure documents the difficult history of the Jewish Heritage in the region. For example, one can trace the changes of functions of Synagogue in Husiatyn and other similar monuments in East Central Europe. Although, in the 1970s, the building was renovated and served as a regional museum, nowadays the state of preservation of the abandoned Husiatyn Synagogue does not differ from its condition after the damage from the 1915.[11] (Il. 8)

Furthermore, such problems as legal frameworks, especially for image rights, are often a part of political reality. Image rights and terms of use are a separate and complicated area of international cooperation, and constitute challenges for cooperative publication of image materials online in many contexts. They were also directly influencing the selection of the image material for the FoKO infrastructure.

Firstly, the preliminary idea of open access had to be examined in light of existing copyrights and local (national/institutional) regulations. The FoKO database includes a large amount of archival material (photographs from the nineteenth and the early twentieth century). According to legal requirements, the owner of the copyright has to be determined. In practice, this is difficult and sometimes even impossible. The image material in the photographic archives has been collected for many years and it often lacks basic information about owners of copyrights. In the case of the oldest photos, we had to search for the owners of the copyright among the heirs of the photographer. If the photographer is unknown, these efforts may prove futile.

Even though some of the image material was new and well described, open access itself turned out to be an issue. The idea is well known and appreciated by the international research community, but it conflicts with the local legal regulations of many institutions, which are often required to derive income from their image resources.

A legal agreement had to be developed and accepted by all international partners. Every subtle divergence of particular image copyrights and terms of use had to be analyzed and discussed. Moreover, the basic terms needed to be determined and compared in different languages and this led to some unexpected dilemmas. For example, the term “Lichtbild,” (synonym for a photograph, literally “Light-image”), which is crucial in German regulations, has no equivalent in the other languages used in the project.

Moreover, the awareness of these problems, the sensitivity to them as well as the tendency to take a certain amount of risk, is different in different countries and institutions.

Nevertheless, the exchange of knowledge and points of view between the researchers was profitable. The integration of contrasting worldviews and strategies sparked many discussions between project partners. It helped to understand other perspectives, and increased our shared knowledge and enabled the juxtaposition of different methodological approaches.

Emilia Kłoda is an art historian currently working in the Lubomirski Princes Museum at the National Ossoliński Institute in Wrocław. In 2017, she received her PhD from the University of Wroclaw (dissertation topic: “Life and work of the baroque painter Johann Christoph Lischka”). She cooperated on the projects “Virtual Museum of Baroque Ceiling Paintings in Silesia” and “Baroque Painting in Silesia” at the University of Wrocław. Until December 2017, she worked in the project “Scientific infrastructure for art-historical monuments in East Central Europe” at the Herder Institute in Marburg. Baroque art, painting in Silesia, digital art history, and art historiography are her main fields of interest.

Ksenia Stanicka-Brzezicka is an art historian, graduated in 2004 with a thesis on Silesian artists between 1880 and 1945 at the University of Wrocław (Poland). 2004 – 2013 researcher and teacher at University of Wrocław, Faculty of Historical and Pedagogical Sciences. 2014-2017 coordinated the project “Scientific infrastructure for art-historical monuments in East Central Europe” at the Herder Institute in Marburg (Germany), since 2018 member of the Herder Institute Research Academy. Participated in many research projects, most of all in digital humanities, especially digital art history. Research also in fields: art and history of East Central Europe in the 19th and 20th century, art, crafts and industrial design, visual production and practices in the humanities, gender studies.

References

Deteriorating Husiatyn, Ukraine fortress synagogue is for rent, Jewish Heritage Europe, <https://jewish-heritage-europe.eu/2014/11/26/historic-husiatyn-ukraine-synagogue-is-for-rent>. Accesed 13 June 2019.

Historical Atlas of Polish Towns, vol. 4, no. 2: Rafał Eysymontt, Mateusz Goliński, Marta Młynarska-Kaletynowa, Wojciech Ziółkowski (eds.), Środa Śląska, Wrocław: University Press, 2003.

Kłoda, Emilia and Stanicka-Brzezicka, Ksenia, Digital History Goes East. A Database Description of Cultural Heritage Assets: Project “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure”, in: “Visual Resources” (2019), DOI:10.1080/01973762.2018.1553443.

Project “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure”. <https://foko-project.eu>.

Tezaurus dziedzictwa kulturowego. Słownik hierarchiczny pojęć dla dziedzictwa kulturowego – narzędzie wspomagające tworzenie i wykorzystywanie baz danych obejmujących zabytki sztuki. <http://sai.bu.uni.wroc.pl:8080/The2/index.jsp;jsessionid=931521B9BFE15274A87B08384962E59B>

Słowniki kontrolowane, Narodowy Instytut Muzealnictwa i Ochrony Zbiorów – NIMOZ. <https://www.nimoz.pl/baza-wiedzy/digitalizacja/slowniki-kontrolowane/aat>. Accessed 12 June 2019.

Zdrójkowski, Zbigniew “Geneza prawa średzkiego i jego rola dziejowa (1223-1511)”, Studia z dziejów Środy Śla̜skiej, regionu i prawa średzkiego, ed. Ryszard Gładkiewicz, Wrocław: University Press, 1990, pp. 53-69.

[1] Deutsches Dokumentationszentrum für Kunstgeschichte – Bildarchiv Foto Marburg, Inv. Nr. fmc1309634; Esztergom, Church of Saint Ignatius of Loyola, Project Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure. <https://foko-project.eu/#/object/de/foko_Object6529f?q=Esztergom&id=foko_Object6529f>. Accessed 12 June 2019.

[2] Project “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure”. <https://foko-project.eu>. See also: Emilia Kłoda, Ksenia Stanicka-Brzezicka, Digital History Goes East. A Database Description of Cultural Heritage Assets: Project “Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure”, in: “Visual Resources” (2019), DOI:10.1080/01973762.2018.1553443.

[3] For example fortifies churches in Romania, Hungary, and Ukraine that are described as “Wehrkirche” or “Kirchenburg”. In the German dictionary of art, there is a slight difference in meaning, but there is no comparable distinction in other languages; or a unique group of churches in Silesia designated by polish researches as “kościół halowo-emporowy” – in English texts was used the German term “Wandpfeilerhalle type”.

[4] Tezaurus dziedzictwa kulturowego. Słownik hierarchiczny pojęć dla dziedzictwa kulturowego – narzędzie wspomagające tworzenie i wykorzystywanie baz danych obejmujących zabytki sztuki. <http://sai.bu.uni.wroc.pl:8080/The2/index.jsp;jsessionid=931521B9BFE15274A87B08384962E59B>. Accessed 12 June 2019.

[5] In 2013 in Poland, The National Institute for Museums and Public Collections (Narodowy Instytut Muzealnictwa i Ochrony Zbiorów – NIMOZ) signed the preliminary agreement with the Getty Institute i The J. Paul Getty Trust to create the Polish version of the AAT, see: <https://www.nimoz.pl/baza-wiedzy/digitalizacja/slowniki-kontrolowane/aat>. Accessed 12 June 2019.

[6] Historical Atlas of Polish Towns, vol. 4, no. 2: Rafał Eysymontt, Mateusz Goliński, Marta Młynarska-Kaletynowa, Wojciech Ziółkowski (eds.), Środa Śląska, Wrocław University Press 2003; Zbigniew Zdrójkowski, Geneza prawa średzkiego i jego rola dziejowa (1223-1511), in: Studia z dziejów środy śla̜skiej, regionu i prawa średzkiego, ed. Ryszard Gładkiewicz, Wrocław University Press 1990, pp. 53-69.

[7] Środa Śląska, Układ miejski, Project Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure. <https://foko-project.eu/#/object/de/foko_Object42897?q=%22%C5%9Aroda%20%C5%9Al%C4%85ska,%20Uk%C5%82ad%20miejski%22&id=foko_Object42897>. Accessed 18 June 2019.

[8] Vilnius, Išganytojo bažnyčia, Project Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure. <https://foko-project.eu/#/object/de/foko_Object1d93d5?q=%22Ko%C5%9Bci%C3%B3%C5%82%20Chrystusa%20Odkupiciela%20na%20Antokolu%22&id=foko_Object1d93d5>. Accessed 18 June 2019.

[9] Воўчын, Касцёл Найсвяцейшай Тройцы, Project Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure. <https://foko-project.eu/#/object/de/foko_Object3625a9?q=%22Church%20of%20the%20Holy%20Trinity%22&id=foko_Object3625a9>. Accessed 18 June 2019.

[10] Jelgava, pils, Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure. <https://foko-project.eu/#/object/de/foko_Object1711f2?q=Mitau&id=foko_Object1711f2>. Accesed 18 June 2019.

[11] Гусятин, Cинагога, Monuments and Artworks in East-Central Europe Research Infrastructure. <https://foko-project.eu/#/object/de/foko_Object1bb185?q=Synagogue&id=foko_Object1bb185>. Accessed 13 June 2019; Deteriorating Husiatyn, Ukraine fortress synagogue is for rent, Jewish Heritage Europe, <https://jewish-heritage-europe.eu/2014/11/26/historic-husiatyn-ukraine-synagogue-is-for-rent>. Accesed 13 June 2019.

Published on September 10, 2019.