Translated from the French by Emma Ramadan and Tom Roberge.

Four years, or nearly. The next four years of the boy’s life, which will be the most beautiful, the most marvelous. The trees were nothing. The elms and the planes and the chestnuts: easy climbs, warm-ups. What he will soon ascend is nothing less than the mountain of civilization. The peak of his existence. The summit of his life on earth. And happiness on top of it all, at his highest point.

After that . . . No, let’s not talk about what will come after. Let’s enjoy this.

Boulevard du Temple. Here’s what it’s like: a charming tableau. A beautiful little family. Emma at the piano, Gustave on the oboe, and the young man, there, seated on an easy chair, legs crossed, silk shirt, starched collar, mohair vest, tight pants rolled up in the English style, Derby shoes in kidskin leather (his own clothes, all new, in his size, made to measure) and even, yes, cuff links in the shape of a lyre at his wrists, it’s him. It’s the boy.

They call him Félix.

Father and daughter play opus 30 n° 6, one of the three “Venetian Gondola Songs” as they were called by Mendelssohn. Gustave transcribed them for his instrument. Emma had to insist that he do so, and in the end he gave in. Exhumed the oboe. Resuscitated it. Gustave carved, scraped, bound the fine strips of wood until the reed was perfect. He pinched it between his lips. He blew. It made him a bit dizzy—it had been such a long time. Fastidious reprise: wrong notes, squeaks, slips, inopportune derailments. In addition to the time off, let’s not forget that the oboe is one of the two most difficult instruments to master—the second being the French horn. Gustave’s kind eyes implored his daughter. (Please, let this old elephant and his old horn go off to the cemetery . . . ) She had not yielded. With practice, and after numerous repetitions, it came back. The sound, the pleasure. When the boy heard the song coming from the salon, he had been transported. Oh! the sluice gates that were opening, the flood, the waves that penetrated his heart, the swell that both submerged and cradled him. Tumult and sweetness. It was the voice of his mother, the rare and precious trickle of words she would suddenly let loose in front of the shack, and which he drank in before the wind carried them towards other realms. They were the crepuscular parabolas that Joseph sometimes unwound at the dinner table, like a blessing. It all came together, harmonized, through a mysterious sonorous alchemy, and it practically made him capsize.

Among the forty-eight songs, it’s the three gondola songs that have the most powerful effect on him.

A new year begins. Night falls. It’s cold outside. A few snowflakes float here and there but never seem to touch the ground. It’s nice inside. The three of them together in the music room. A new kind of trinity—“Father, Daughter, and the Simple Spirit,” one of their visiting friends mocked. They celebrate the Magi in their own way. The piano is an Érard, a baby grand piano. The oboe a Buffet- Crampon, not ebony, but grenadilla. The wood shines like black lacquer in the light of the big, four-armed chandeliers. The easy chair is blue velvet.

It develops into a routine. And not limited to Mendelssohn; the repertoire is vast and grows ever larger from week to week. Studies, preludes, nocturnes, fugues, ballads, sonatas, scherzos: everything. Everything is worthy. The important part is in the communion. Osmosis. In those moments the bonds between them tighten, until there’s nothing between them but affection and grace.

When they’re not playing their instruments, they go to a concert, to the opera. The first time, the boy had been flabbergasted, glued to his seat, clutching onto it. The imprint his fingers left in the fabric of the armrests was visible from afar.

Love and art, as Emma said.

She wanted to teach him. Piano, music. She had a half-dozen students, little girls from six to sixteen years old, to whom she gave weekly lessons. She had asked the boy to attend as well. Then she began to give him private lessons. But it didn’t work. Seated at the keyboard, there was a block. The boy understood the advice and instructions, he intellectually absorbed the exercises, but when it came to reproducing them he was incapable. Total paralysis. Just as with words: they simply didn’t come out. And it certainly wasn’t unwillingness on his part, he enjoyed these lessons and did his best— even if, in truth, it was mostly to please his professor (and, in the truest truth, because a small release shook him every time the young woman touched his hand, his fingers, his back, his chin, in order to correct his posture). Not long after starting, Emma had abandoned the effort.

Likewise for reading and writing. After a few hours spent playing school, she had had to admit the failure of her attempts. And their vanity. For in the end, if she hadn’t insisted more, it was because she felt it all risked spoiling the boy, distorting his personality. Inevitably it would have an influence on his spirit, on his way of understanding the world and the things in it—gentle corruption, but corruption all the same—and it was exactly that mode of thinking and that spirit, personal, unique, that fascinated her and that she wanted to preserve at all costs. The teaching she and her peers had received, the education that had been given to them was certainly a window open onto liberty, but wasn’t it also a cage? Wasn’t it a mold, rigid and functional, from which everything was created, fashioned identically? A single model—designed by whom, destined for what?

Until now, the boy had maneuvered in the margins, outside the precepts and rules. So, let him continue! was what, in essence, Emma said. When she observed everything around her, the people who constituted the supposed polite society, what did she see?

Life is elsewhere.

The Van Eckes have introduced the boy to a few select friends. Telling, in minute detail, the circumstances of their encounter, the accident, the convalescence, the mystery of his identity and his origins. The story inevitably engendered all sorts of reactions and comments. The boy’s loss of speech, in particular, intrigued them, and, ironically, unleashed their tongues. Every person had their opinion on the subject. When they broached it, Gustave became ashamed, he’d always thought that the crash with the car was the cause of this problem, and consequently deemed himself largely responsible (an intimate conviction that would remain forever stuck in him, like a tiny metal sliver in his flesh). Outside of this limited circle, the introductions were made over many days and at random. Passing some acquaintance, some relation, they took advantage to introduce the boy—Félix—without explaining or expanding. They replied to the questions evasively. With an attitude that made the presence of this stranger seem like the most natural thing in the world, the same as if a distant godson or second cousin had recently arrived from the provinces. But it had the opposite effect, at first. Far from appeasing curiosity, their discretion aroused it. People talked, people gossiped. They embellished, extrapolated. The second cousin became a phenomenon—I heard that the widowed man has a farmhand . . . A retard . . . Apparently hunters found him in the middle of the forest . . . Would you believe he was raised by a pack of wolves . . . Have you seen the size of his teeth? . . . A missionary, yes, brought him back in his luggage . . . He only eats raw meat . . . Half savage, half . . . I was assured that he eats roots exclusively . . . From a primitive population, over there in who knows what jungle . . . And his eyes, have you seen his eyes? . . . The Arrapaos or the Parrareos, something like that . . . He sees in the dark as well as you or I see in the middle of the day . . . I swear his howls send a shiver down your spine . . . Half monkey, half . . . The Rapparaos, that’s it! And suddenly the curious started to parade through their home, exhaust- ing every far-fetched pretext, every harebrained stratagem, to come get a look for themselves. Never had Gustave and Emma received so many visitors. People went to the Van Eckes’ home like they went to the zoo or the natural history museum—or, more cruelly, to the freak show—and they often returned disappointed, because the boy had not perched on the back of an armchair or climbed the curtains, he had not shown his fangs or tried to bite anyone. (Should we demand a refund? At least compensation for lost time?)

Father and daughter had finally understood what was going on. Nothing could have offended them more, especially since they’d taken special care not to exhibit their charge like some vulgar attraction.

“Have you got your tickets?” Emma had said to put an end to it, scowling at the umpteenth curious neighbor who was standing on their landing (a fat lady patroness flanked by two kids dressed as if for the village fair), before slamming the door in her face.

A door that was now only opened sparingly.

Henceforth they were selective. The identification that visitors had to present was the purity of their intentions. Emma and Gustave conferred, evaluated, judged, before granting or denying passage.

Despite that vigilance, they were deceived a few more times. And so on one afternoon, Gustave unleashed a terrible wrath. Their guest that day had seemed above all suspicion. Pierre-Henri Louhans-Mainaut was only a teenager when Gustave had met him, some thirty years earlier. The nephew of a fellow botanist, he often used to accompany his uncle to conventions. Now an honorary member and patron of numerous agronomics societies, to which he’d donated a portion of his inherited fortune. No longer part of that scene, Gustave now only saw him from time to time.

Everything had gone rather well until he was about to leave. Two hours straight they had chatted in the living room, drinking tea and coffee. The boy was present, but their guest had only asked a few questions about him. Rare were the looks he accorded to him and not a single time had he spoken to him. A vase, a lamp had kept more of his attention. On the other hand, the man’s features bloomed whenever his eyes landed on Emma, so much so that the young woman had come to the conclusion that the visit’s sole purpose was, in reality, to get close to her: the discreet beginnings of a courtship. Which was true.

But as he was about to leave, Pierre-Henri Louhans-Mainaut had gotten up and, still without looking at the boy, addressed him for the first time. And to say what? Simply to tell him to go get his coat. Words all the more humiliating because they seemed so natural in his mouth (that tone, that air). Emma’s delicate jaw dropped open. The boy, in his innocent affability, was already carrying out the order when Gustave’s voice erupted.

“Félix, don’t move!”

That tone, that air . . . The three others, surprised, turned towards him. The old man’s eyes had the cold glare of a razor blade. His pale face had rapidly turned purple. One could see the blood fill him, climb, from his neck to his forehead, like a dark wine poured into a glass carafe. When the color had reached the roots of his hair, Gustave exploded.

“What right? . . . How . . . How dare you . . . ? He . . . He . . .” He was stammering, stuttering, spitting. “He’s not a servant! Who do you think you are? For God’s sake, that boy is not your valet!”

And Gustave the wild boar continued like that, growling, trashing, raving, and advancing towards their visitor, who, frightened, retreated under duress, retreated, retreated, until he stumbled over a low table and tipped backwards, frantically but vainly clutching at the air, and dropping heavily onto his behind, a scene that unleashed in the boy, in his innocent spontaneity, a burst of his thunderous laughter.

Oh how Emma had admired her father in that moment. How proud she had been of her dear, very dear Papa. When she stepped in between him and the odious man, it was mainly because she had been afraid that Gustave would have some kind of apoplectic attack. Without a word she walked Pierre-Henri Louhans-Mainaut to the exit, handing him, in passing, his infamous coat, which he did not even take the time to put on, fleeing as quickly as possible, clothed only in his shredded vanity.

Adieu, unsavory character.

Finding her father back in the living room, Emma forced him to sit back down, loosened his tie, made him drink a big glass of water, and then, reassured, finally allowed herself to enjoy the hilarity, mixing her own cascade of laughter with the boy’s.

This episode closed the book on visitors. In fact, all interest in the phenomenon waned. Novelty doesn’t last, we grow bored as we become impassioned: quickly. The affair had hardly lasted three months in their small society. Now they are left in peace. They are free, Gustave, Emma, Félix, to revel in the essential: love, art, and Paris.

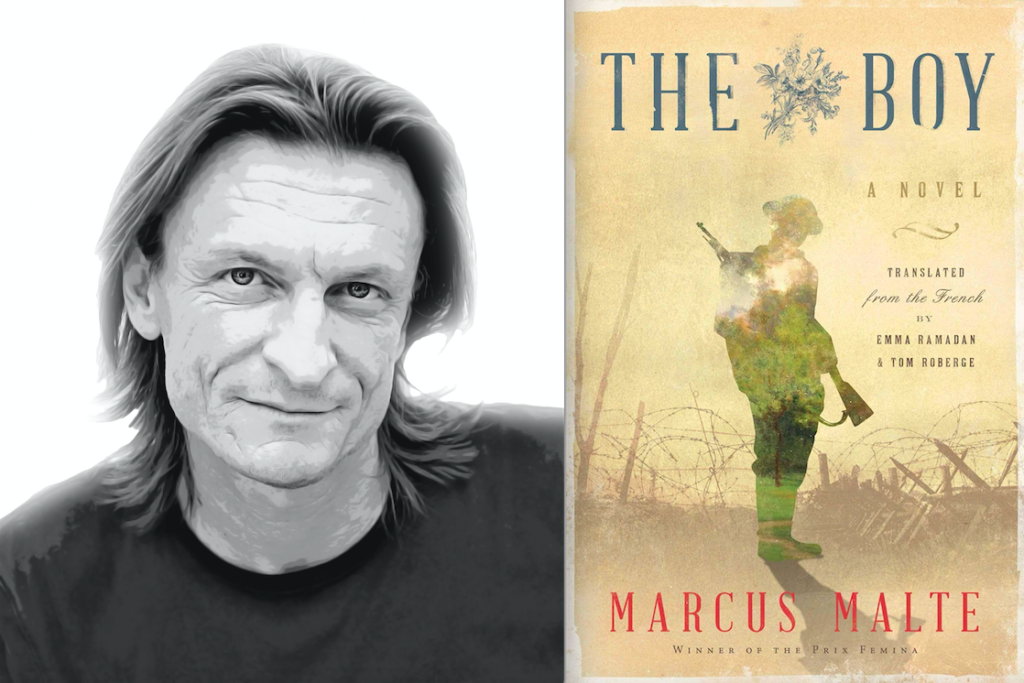

Marcus Malte was born in 1967 in Seyne-sur-Mer, a small harbor city in the south of France, along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. As a child, Malte immersed himself in literature, discovering the novels of John Steinbeck, Albert Cohen, Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Jean Giono. He began writing in elementary school and chose to major in film studies after graduating from high school. At twenty-three, Malte became a projectionist in Seyne-sur-Mer’s historical movie theater and soon wrote his first short stories. Later in the 1990s he began reaching broader audience with a series of novels, a couple of hard-boiled detective stories where Malte created the recurrent character of Mister, a jazz pianist. His fiction includes Garden of Love his first real success (rewarded with a dozen literary prizes, including the Grand Prix of the readers of Elle, police category, 2007) Les Harmoniques (Prix Mystère de la Critique, 2012) and more recently Le Garçon (The Boy) for which he received the famous Femina Literary Prize (2016). The Boy is his first novel to be translated into English.

Emma Ramadan is a literary translator based in Providence, RI where she is the co-owner of Riffraff bookstore and bar. She is the recipient of a PEN/Heim grant, an NEA translation grant, and a Fulbright fellowship for her translation work.

Tom Roberge is co-owner of Riffraff bookstore and bar in Providence, Rhode Island. He learned French as a Peace Corps volunteer in Madagascar and was formerly the Deputy Director of Albertine Books, a French language bookstore in New York.

This excerpt from The Boy is published by permission of Restless Books.