1. The Vision of Eating

The gastronomic cliché of our times is that we eat with our eyes—a shorthand which asserts how food looks matters. Had Jackson Pollock copyrighted his drips, half the world’s fine dining venues might be bankrupt, revealing a restaurant industry whose visual vocabulary may be far shorter than advertised. But why advertise at all? It’s counterintuitive that organic matter with the vital duty of imparting nutrition should undergo aesthetic scrutiny at all, particularly as it is consumed orally then passed. The fashion industry shows us how fields not strictly visual are easily infiltrated by the conceptual pull of vision; for many, how bodies are kept warm is ipso facto a matter of looking. So if visual style must be fixed into our culture, what should it do? Is a problem like ugly food simply marketing? Could stylishness undermine our collective vision?

According to Larousse Gastronomique, (occidental) restaurants have been around since the mid-eighteenth century. Since then, the basic formats of food presentation are unchanged. Most prepared foods we enjoy are solid, moist, and fragmented, so the plates and tables they rest on must be flat for the offerings to be stable. If we ate lying—as was fashionable for ancient Greek and Roman elite—foundational change in presentation might quickly emerge. Beyond ergonomics, human health governs much of food’s visual dynamics. (Part of why we don’t lay to eat is to limit acid reflux.) We’re fond of smooth plates for their ease of cleaning, and food’s scale is governed by human sustenance; I would not want to see Anish Kapoor’s Leviathan redone in tempered chocolate, no matter how awesome it looked, for it would be a terrible waste. (In art, it can be conjectured that so long as the article is art, it is not waste.) Finally, and obviously, food must be edible, limiting the ingredients for aesthetic expression. So if the visual variables of food are actually quite limited, what are we truly classifying visually? The ubiquitous logic which tells chefs that salmonella is not an ingredient worth sampling doesn’t apply to visual artists, free to use anything to express meaning; perhaps this is what the surreal cliché gets at; that mouths yearn to taste the fullness had by eyes.

Formally hybridizing visual art and gastronomy by forcing the formats together seemed a way to at least ponder why eating wants so much to do with seeing. Recalling many enlightening visits to MOMA and the rare treat at its upscale restaurant The Modern, I chose this unified setting to contemplate food via the precepts of visual art, to figure out what it was to eat with one’s eyes.

2. Miró via Eye and Mind

MOMA was showing Joan Miró’s The Birth of The World. A proudly Catalan artist who lived through the many horrors of twentieth century Europe—including the Spanish Civil War—Miró worked in several mediums, work famed for its playful engagement with the subconscious. A reputedly ordered man, Miró’s stylistic experimentation lead to childlike pictorial depictions others called surreal, though André Breton, the surrealist progenitor, considered Miró’s work symptomatic of some “arrested development,” more naïve than fantastic. No matter, for Miro was never a man prone to the pomp and circumstance of manifesto makers like Breton, possibly turned away by outside powers given Europe’s embattled century. Miro revolutionized painting as a personal task and it was the very independence inside individuals Miro was drawn to paint, painting inner life to free the form of painting from the bourgeois society of fine art.

Miró’s work has always evoked fondness and respect in me. Recently, in Monopoli, Italy, I saw a Miró exhibit of paper works whose color combinations left me sure that Miró knew much about simplifying choice. When Miró makes quartets of blue, red, green, and yellow, he picks hues that refuse a tertiary vocabulary. In his mature style, Miró’s forms, glyphs, and Klee-like figures offer the unthreatening simplicity of basic shapes. It is these features and what they communicate that not only create serenity within me but advocate the importance of quietude. I also always go close-up, to see how Miró applied paint, an artist, like many, who leaves traces. Contemplating quietude coupled with a technical analysis generally leaves me satiated. Miró seemed a fitting pair with the food at The Modern, an artist whose work is light and playful—positive connotations in the West’s restaurant scene.

As I shuttled uptown on the subway, I wondered, does this make Miró an amuse-bouche? Or should I have Miró instead of a dessert? It was the first time I’d measured art with the ruler of food, and instantly this exercise in substitution brought out Miró’s serious side. (This alone, recommends such tests in intellectual synesthesia.) Often, Miró’s composition holds an audience captive through intent sparseness, precise as hieroglyphics to an archeologist’s child. A master of negative space, Miró imparts focus to force his audience to submit to organized visual formats arranged exactly to evoke mystery: the more pristine the arrangement, the deeper we enter the work’s unknown. So, the channel between Miró’s artworks and meaning is tight and direct—so direct, that it sometimes does not even bypass its creator. Mystery is worth arriving at quickly, his works seems to say.

No, Joan Miró is no starter. In the three-course lunch I’d planned, it was right that Miró be the main course. And that was that.

3. Consuming Restaurants

Happy to take walk-ins, The Modern became my test ground. Through his eyes, the young maître’d betrayed suspicion, probably as I’d worn an Eminem-style sweater hoody (it was a freezing day, plus I’d come from the painting studio). Under-forty maître d’s at high-end restaurants are often caught up in manufacturing personas that fit their place of work; it can take decades for a personality to emerge, (if it ever does,) personality that should add to the venue, not mimic its ambience. But this dubious glance did effectively remind me that dress codes in prestigious restaurants are tighter than even the finest art halls of the world. Keeping shtum, I took a bar seat.

The bar of restaurants like The Modern often claims to offer a

different ambience to the main hall—architecturally, The Modern’s bar and lounge are even sectioned by a wall. I find

these casual zones anything but casual, as feigned relaxation is always tenser

than simply acting rigid. Although the hierarchy between staff and patron

contracts at the bar, façades are still complicated, particularly for patrons

who can’t afford to be in such rooms regularly. How you act is important.

One example comes through the common practice of being offered sparkling water without an announced price, though the itemized check always reveals an inflated cost. Restaurateurs exploit patrons who would not otherwise pay the inflated price if listed, by bullying patrons into accepting a rhetorical offer, under the guise that a fine service is offered. Surely I can’t be the only one who has felt gauged by this entirely vulgar strong-arming.

Though Michelin-starred restaurants make good archetypes, even the simplest diners contribute to a similar category of social dynamics, an ongoing loop of coded behavior between proprietor and patron where both civilize each other. The vendor promises a patron hospitality through deference—“how may I help you”—and the greater deference the more luxurious the venue, deference which allows patrons to dominate their subjects, environment, and acquired chattel. Conversely, customers keep the customs of the establishment, both subtle and obvious. In some bars you never curse. In nightclubs you dance. Brothels tender sex.

There are customs in art museums too, I reminded myself, but art’s customs often regard prohibitions that sum to stillness: no flash photography. This stillness isn’t encouraged for tranquility or grace, but for its democratic use catering art to viewers. Most art venues cater a similar way, showcasing art that is substantially different. Hospitality venues, however, vary greatly in their ambience and price, though their ingredients are more similar. Therefore, in restaurants, arguably, ambience is most of what one pays for, ambience that arrives through the eye.

4. Back of House

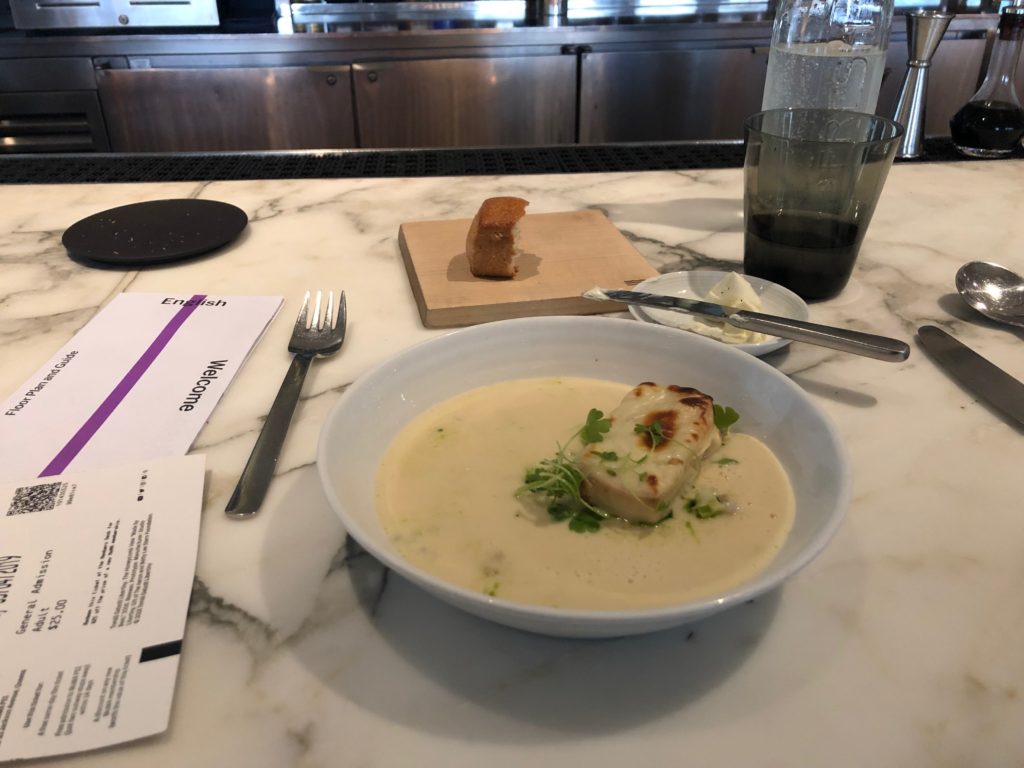

I ordered an appetizer of celeriac soup with Bayonne ham and fontina cheese. Soups are light and so is Miró, I thought. I didn’t know anything about fontina and neither did the barman, as it turned out, but what he could say was that the dish was somewhat of a croque-monsieur in soup—the sort of whimsy that goes with Miró, I thought.

Tiny cubes of gram flour bread came beside three squirts of crème-fraiche butter shaped like Hershey’s kisses. Gestures like these contain the delight of form as function, but also render the food decorational, as such offerings are often unfinished.

Sensing my inquisitiveness, the barman began filling me in on the house sparkling water. “There’s a CO2 system back there,” he said offhandedly, bridging the very status divide that sets his wage. Was it my sweater that signaled I was the type of diner happy to openly acknowledge such a thing as a “back there.” Or was he an ambitious visionary desperate to dismantle barriers separating the lofty front of house from the raw reality of the back?

For art, an intellectual “back there” adds to viewer understanding. In the Miró show I was about to see, the show’s title work—a single large painting—was supported by roughly sixty appendix works and program notes that contribute to the overall sense of a “back there.” And the metaphysical “back there” of all art is what gives art sustained value, through familiar and disguised modes: art history, the mystique of artists, interpretation, the secrecy of markets, and even culture at large. An alternate term for culture’s back of house is education.

The barman’s utterance of a chemical formula broke the ambience, and that teleological clash alerted me to a major difference between restaurants and museums in their mismatch of educational promise. I began to ponder what other expectations differed, and, grateful my glass of sparkling water had not tumbled away, relied on a table to lay out some simple ideas.

5. Comparing Difference in Intended Expectations between Restaurants and Art Museums

| Desired Expectations of | Deliverables at Restaurants | Deliverables at Art Museums |

| Contractual Merit (strict) | Access to – venue – food preparation – service Acquisition of food Check | Entry ticket Access to – venue – proper display of artworks – proper maintenance of artworks – curation – artworks |

| Merit of Deed (condign) | Acquisition of subjective quality via subjective appreciation modes: – oral taste – memory – association – emotion – fun – meditation – social gain – etc. objective modes: – analytic – relative – standardization – ideological – technical – etc. Consistency Satiation of appetite | Acquisition of subjective quality via subjective appreciation modes: – aesthetic taste – memory – association – emotion – fun – meditation – social gain – meaning – etc. objective modes: – analytic relative ideological technical meaning etc. Acquisition of education via – information – recognition – comprehension – experience |

| Surplus Merit (congruent) | Acquisition of positive emotion* Acquisition of education via – information – experience Acquisition of insight via – knowledge – enlightenment – transcendence | Acquisition of (any) emotion* Acquisition of insight via – knowledge – enlightenment – transcendence |

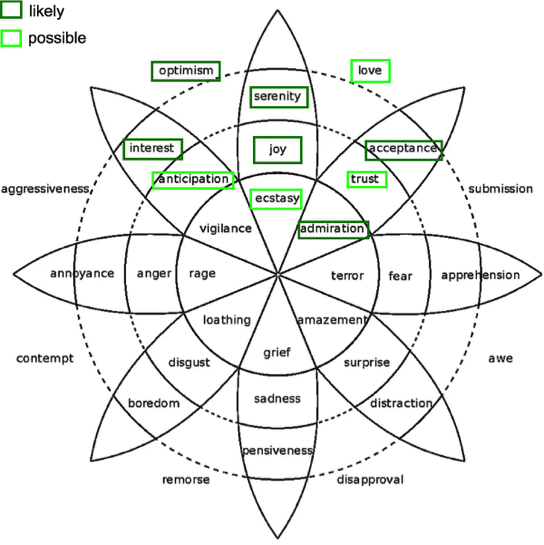

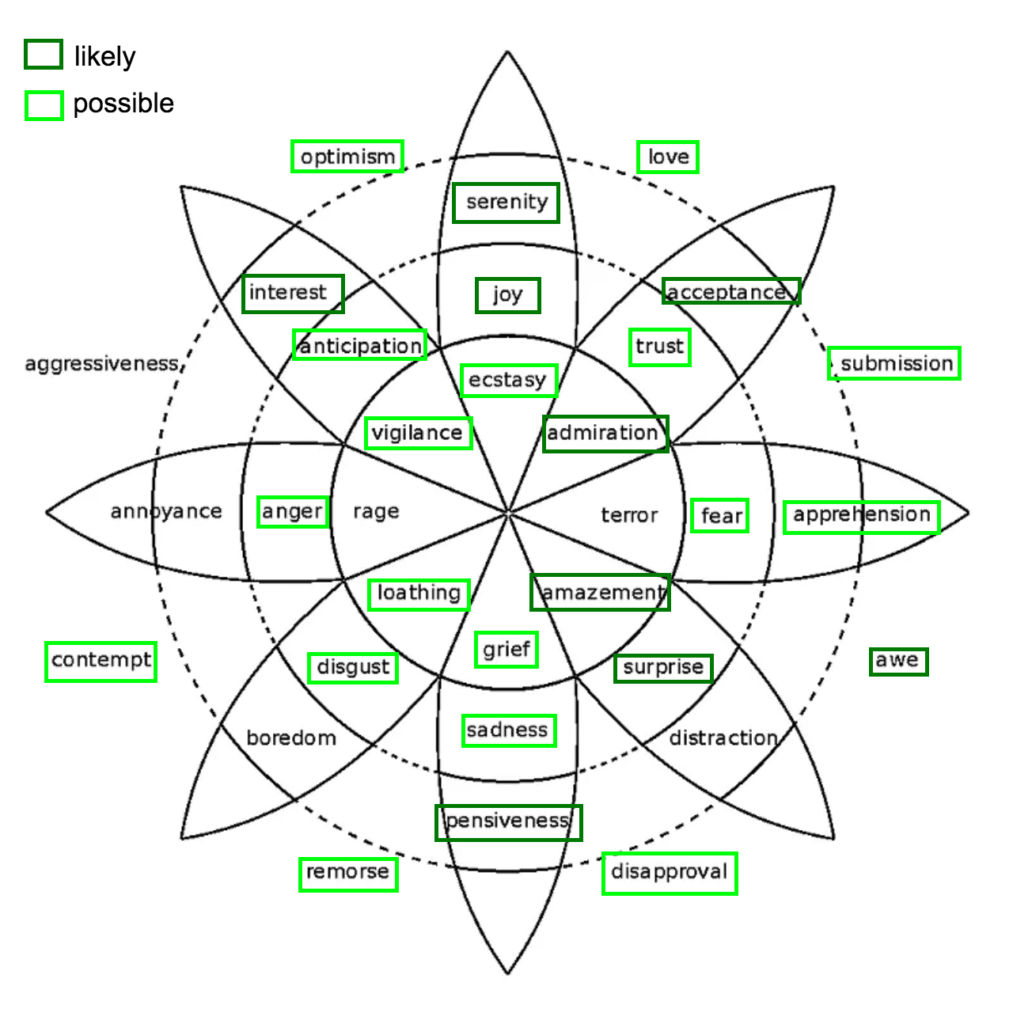

*Comparing difference in intended emotions acquired between restaurants goers and art museum visitors via Plutchik Wheels

Food

Art

6. God’s Triptych

Roman Catholics understand merit in three tiers: strict merit, giving an action what it is due contractually, like wage for work; condign merit, merit earned from deeds but under the sphere of promise, like through work of high quality; and congruent merit, obligation-free, often unexpected merit, akin to benevolence.

See from the table that restaurants don’t promise education as a matter of quality, and that even at the deepest level of merit, restaurants don’t engage non-positive emotions as a gain. (Admittedly, the Plutchik Wheels are personally appraised, though I’m confident most opinions will be similar with respect to the general zoning, and range of emotion associated with food and art.) This means restaurants are emotionally normative, in other words, they want you to feel good, which seems obvious, but is worth considering. Truly important food experiences differ, for instance, some unexpected taste that reminds you of a grandma lost to age, bringing about sadness, pensiveness, and awe. I consider this to be food’s best aspect and chefs often claim the same.

Art has a substantially higher engagement in meaning, and another term for this transfer of meaning is communication, perhaps art’s chief purpose. While the restaurant goer’s subjective assessments is the chief factor of condign merit, the museum visitor appeals to external standards. Education (mostly through the artworks themselves) is a basic expectation in museums. This educational asymmetry implies why standardization is not the concern of art lovers, who rarely preference art due only to prizes, but rather, due to what the art evokes. In contrast, wines to hams are designated with standardized qualities along agreed-upon metrics i.e. the percentage concentration of chocolate.

This may be because restaurant goers in a technocratic world like to know what’s in the chattel they acquire; it’s always my soup, yet in museums, always the Nan Goldin. Art viewers (and even owners) are content to know only vaguely what constitutes artworks through scant words describing of medium: oil on linen. The artist’s name somewhat replaces standardized merit schemes, perhaps as works are unique and rarity is desired. A great dish, however, wants to be remade consistently, and tried by many. Here lies every fine restaurant’s paradox; it hopes to sell often but to an exclusive few, inducing increasingly complicated social reactions, which borrow the desired rarity of art. The current global trend sees higher spending of disposable income in hospitality from a broader class set; this adds to the complication. Food’s advantage over art in dissemination has made cuisine the most quickly democratized cultural arena of the twenty-first century, owing partly to media’s efficiency in raising awareness. But restaurants, particularly in “fine dining,” run the risk of pushing apart the very status hierarchy food can bring together by using visual aesthetics, design, architecture, and notions of ambience to increase the social barriers of entry—all justified through price. If food is to elevate itself as a cultural form to the status of literature or music, education must form part of restaurants, to replace the abundant props and posturing. This means food should also contain useful and evocative ideas by employing meaning as an ingredient, a mammoth challenge for chefs and restaurateurs, but one they have begun. Meaningful restaurants will allow restaurant goers experience of great insight.

I hope diners will one day dine at more tables of knowledge than status, a tremendous challenge given the intoxications of status. The great worth of aesthetics is that it can buttress knowledge, as shown by museums that make a noble business of bringing about public education and enlightenment, if not transcendence. Food should use aesthetics better.

7. Test Results

When my celeriac soup was poured at the bar, I furrowed my brow. To pay $18 and see the remains of a pouring jug wasted is pure pretense, and a middle finger hoisted from restaurant owner to chef, one of many examples of ambience negating food intentionally.

Did the dish look like art? In the sense that the croque monsieur was off-center and a choice had been articulated, yes. Beyond that, plates of food never really do, partly because plates— empty or full—look like the mass-produced commodities they are. But visual clichés are often capitalized on by restaurants, clichés that are slow to change, because of high yield. For example, this soup was sprinkled with microgreens, which restaurant diners have tasted for over a decade, diners who all know that though they look cute as hell, they basically taste of nothing. Chefs know too, because if they believed microgreens tasted good, they’d make soups and sauces from only them—so far, not one intelligent chef has. But, because emotional positive reinforcement is the cornerstone of restaurants, the industry’s slow cycle of aesthetic vogue goes by without the good scrutiny that makes innovation.

Eating with our eyes is an act of classification, and we govern cuisine through the social status gained by improved aesthetics (even if that use of aesthetics is a detriment to the aesthetics themselves). There is a similarity between microgreens and bail bonds, both objects that keep patrons from social exclusion. But beauty should belong to everyone and nature is strong proof. Though status symbols are here to stay, they should be as fresh as the microgreens that constitute them, if freshness and innovation are metrics that even matter. Real status should be earned by virtue, and food culture owes it not just to its public, but to its ingredients to act with vision.

By the bottom of the soup bowl, I felt drained. I took an escalator up to the Mirós and viewing the artwork left me suddenly nauseated. Miró’s painterly textures looked like vast slabs of luncheon meat, and his once-whimsical glyphs, like hairs to be caught in the throat. The Birth of the World hadn’t the clarity I expected, and, awash with grays, infiltrated the celeriac soup with its moody mystery.

Not wasting a bite, I cast my eye over all sixty works, and felt funnel-fed with ideas, like a foie gras goose. The results of my formal gluttony were a feeling of bloating before the three-courses were even through. Engorged, I wondered if my hopes for restaurants were beyond human ability, but what I did confirm, was that seeing a single important painting rendered ambience a trivial if not vulgar expression of visual aesthetics.

Returning to The Modern for my dessert, the aesthetics of fine dining felt disenchanting. The memory of my black walnut financier is faint. I barely tasted at all. My dessert’s technical prowess was redoubt, but the worth of all its subjective joy was overshadowed by the monumental nobility of MOMA and what vision can stand for.

8. Conclusions

Today, cuisine is not alone in having visual aesthetics infiltrate its core, but more visual influence isn’t always virtuous. The consequence of style warrants study, and simple format swaps study culture surprisingly well. Stapling art with food, I was reminded that eyes are not chiefly for consuming pleasure, but for seeing clearly, and that society may have forgotten this.

Art museums teach that pleasure is not the only point of culture, though food, and the environments of luxury, remind us just how complex taste in a social world is. For now, thinking is free, so new concepts can mediate a capitalist culture and its ostentations, though, admittedly, even the discovery of concepts has a cost: time, efforts, and in this case, $68.55 of ticketing and checks.

If taste matters at all, it should matter not just in color or garnishes, but at the root constituents of culture. Restaurants and museums alike could improve by questioning their responsibility to civilization. True vision is a worthy matter of taste, and makes not only immense artists and unforgettable chefs, but civilians of merit.

Mark Chu is an Australian painter, and a past writer for Melbourne’s Good Food Guide. Mark has been accepted to attend the Complex Systems Summer School at the Santa Fe Institute this June for his research proposal on establishing a scientific classification system of art.

Published on April 5, 2019.