Translated from the French by Adriana Hunter.

I was informed that my stepfather had died when I was called by Bichat Hospital while I was at the PEN Festival in New York. I’d set off for the United States when he’d already been in intensive care for a week. Still, his condition was not deemed to be life-threatening, and it didn’t strike me as vital to stay in Paris to visit a man in an induced coma and pretend to support my mother. I called once a day and grasped that Guy’s condition was deteriorating, with an endless round of alternating antibiotics and anti-inflammatories proving ineffectual and ultimately lethal. I was happier not being there. It would have been even more ignominious simulating affection than revealing my indifference to medical staff who have seen it all and can’t be fooled.

I never liked my stepfather, and I can’t believe that this absence of affection was not reciprocated. There was, as they say, no connection.

I was eighteen months old when he married my mother. The job of father was very much vacant, but he was in no hurry to snap it up, and anyway, I wasn’t especially disposed to his taking it. In the end, the position was never filled. Some people will draw conclusions from reading the study by Pedersen et al. (1979) about a father’s determining influence on a male child’s cognitive development. For anyone else, let’s say the father figure chose another route.

Guy and I never saw eye to eye. I have no recollections of tenderness, or empathy, and I can’t have been much older than the age of reason when I decreed that he was a moron—a premature verdict, granted, but one that was not later invalidated.

I remember once unleashing a personal opinion at home. It must have been inadvertent because it wasn’t something I did frequently, given that I was never satisfied by the debates prompted when I expressed my ideas. On this particular occasion, I was eleven; it was during the upheavals of May ’68 and I’d made what—I admit—was a sweeping pronouncement, calling de Gaulle’s minister for interior affairs, Michel Debré, a “dumbass.” My step-father retorted that “if he was such a dumbass he wouldn’t be where he is.” I immediately identified this statement as servile stupidity, although the formula that spontaneously came to mind was, “This guy’s such a dumbass,” which proves that the word “dumbass” came to me readily. I chose not to waste my time on an unproductive conflict, a decision that, on the threshold of adolescence (a phase well suited to so-called character-building confrontations), is proof in equal measures of wisdom and a superiority complex.

My stepfather respected every form of authority—be it hierarchical, police, or medical—and it so happens he also obeyed my mother. Weak with the strong, he was quite naturally strong with the weak. He was a teacher and enjoyed humiliating his pupils, taunting one in front of the others. That was his teaching method.

Born in late 1931, Guy was twelve when Paris was liberated at the end of World War II, twenty-five when events in Algeria stepped up a notch. A lucky generation but also a misbegotten one, their teenage years shoe-horned between the Occupation and the Algerian War of Independence. He was born too late to collaborate with the Nazis, too soon to torture North Africans. There’s nothing to prove he would have done either. Even performing despicable acts takes a bit of moral fiber. He probably wouldn’t have had it in him to refuse climbing up into a watchtower.

My mother and Guy were that rare thing: a loveless codependent couple. She was never without him, he was never without her, they were never together.

Guy’s death didn’t bother her either way, except that it heralded true solitude on a day-to-day basis, and she could not yet envisage this for herself. On the other hand, it was crucial that she shouldn’t be suspected of this indifference. Keeping up appearances was a social activity that had always strenuously mobilized her energy. Which is why my mother had gone to the hospital every day, because this—as she kept telling herself—was what duty required. She would take a sudoku and sit beside her deeply comatose husband, but boredom would settle in all too soon. She would resist it for a while, then couldn’t help herself asking a nurse or a doctor for some excuse to justify her imminent departure. “I’ll have to go home,” she would say. “There’s no point in my staying here, is there?” Bolstered by some such dispensation, she was then quick to flee.

So I heard that Guy had died when I was in New York. I handled administrative questions long-distance. Then I went home. For the funeral.

That’s when I discovered that my mother was crazy.

Let’s be clear on this.

I always knew my mother was crazy but I won’t be discussing that here.

She had lost touch with reality long ago, but her husband managed everyday issues in such an orderly way that he had succeeded in disguising the evidence. After his death, my mother’s madness descended into burlesque.

The morgue was almost deserted. There were five of us, maybe six.

The servants of death otherwise known as funeral parlor staff have a vocabulary all their own. My mother had hers too, a rather more immediate one. There was no common ground.

When the body had been laid out and nestled in the coffin’s silk lining, one of the men in black came through to the waiting room and asked my mother gently, “Madame, would you like to view the deceased?”

“View him?” my mother asked indignantly. “He’s not some house I’m thinking of buying, he’s my husband!”

The man must have heard it all before, and he went on with his detailed protocol. He wanted to know whether we would like the coffin to stay slightly open so that, in keeping with a rather morbid tradition, family and friends could catch one last glimpse of the loved one. But this was how he put it:

“Would you like us to do an exhibition?”

“An exhibition of what?” my mother asked anxiously. Then she added (and the rationality of it reassured her), “He had a lot of neckties.”

The undertaker looked at her, perplexed.

Eventually the time came to screw down the lid. There was no one there anyway.

“We’re closing, madame.”

My mother glanced at her watch.

“Do you close for lunch?” she asked fretfully.

I laughed. And that’s when I realized I was a monster.

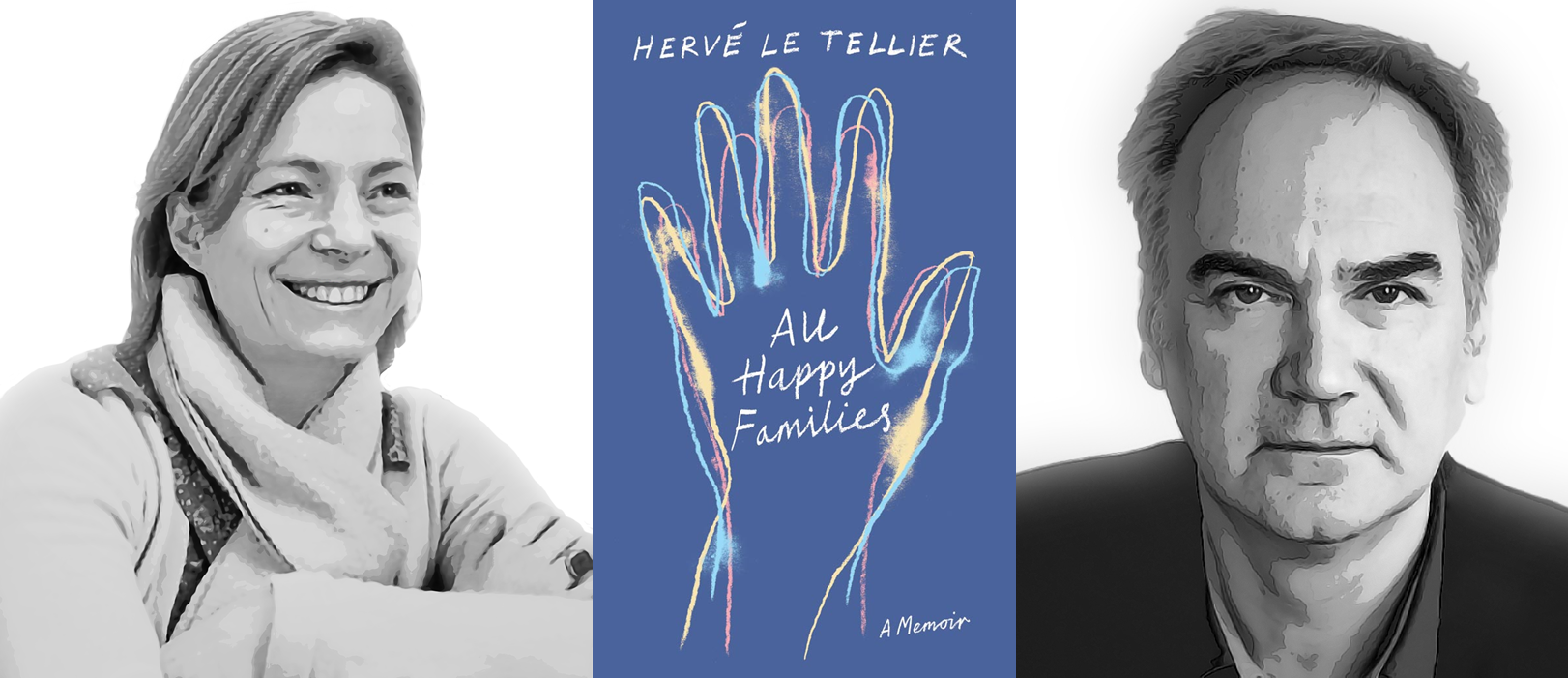

Hervé Le Tellier is a writer, journalist, mathematician, food critic, and teacher. He has been a member of the Oulipo group since 1992 and one of the “papous” of the famous France Culture radio show. He has published fifteen books of stories, essays, and novels, including Enough About Love (Other Press, 2011), The Sextine Chapel (Dalkey Archive Press, 2011), and A Thousand Pearls (Dalkey Archive Press, 2011).

Adriana Hunter studied French and Drama at the University of London. She has translated more than fifty books including Electrico Wby Hervé Le Tellier (winner of the French-American Foundation’s 2013 Translation Prize in Fiction). She won the 2011 Scott Moncrieff Prize, and her work has been shortlisted twice for the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. She lives in Norfolk, England.

Excerpted from All Happy Families by Hervé Le Tellier, published by Other Press on 26 March 2019. Copyright © Hervé Le Tellier. Reprinted by permission of Other Press.

Published on March 5, 2019.