This is part of our special feature on Crime and Punishment.

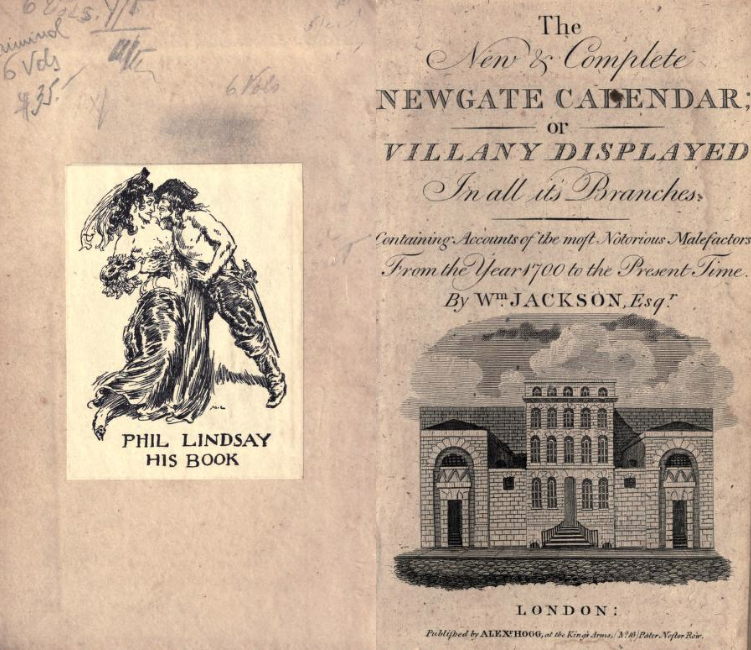

In late eighteenth-century British households, even a few shillings above bare subsistence, The Newgate Calendar, an omnibus of crime stories drawn from court records and newspapers, might have sat on the shelf with the Bible and a copy of one of the many bestselling almanacs published in Britain: The criminal law, the Gospel, and the weather were pillars of British cultural life. The Calendar, first published in the 1790s and regularly in print through the early Victorian era, shows the place of the criminal law in many Britons’ image of their country at the beginning of a nineteenth century in which Britain would reach the zenith of its imperial power. The stories in the Calendar are titillating but nearly all end the same way: A judge, a conviction, and a drop from the scaffold, accompanied by an “improving” reminder to the reader that the law did not see distinctions of rank, and that God’s Providence worked in the courts as well as in affairs of state. The vast majority of people punished by the British criminal courts, then as now, were poor and desperate, but the Newgate Calendar featured a relatively high proportion of gentry and aristocracy. The message readers were meant to learn was clear: British justice was universal and impartial.[1]

In practice, there was a law for the rich and a law for the poor in Britain. In the British Empire, there was a law for whites and another for everyone else. Courtrooms were officially blind to race, but racism was everywhere. In British India, ideas about the particularly delicate viscera of South Asian people were brought in as evidence in cases where whites were accused of murdering Indians. How could a white man have known that his brown servant’s spleen or liver would rupture from a “mild” beating, causing a mortal injury?[2] In the 1880s, in the North-West Territory of British North America, soon to be folded into the Dominion of Canada, Indigenous defendants were convicted or exonerated based on the evidence of colonial officials who claimed expertise in “native” culture and psychology.[3] The law was often enforced with punctilious attention to formal impartiality, but courtrooms easily became echo chambers for expert witnesses who insisted on the existence of biological differences between races and on Britain’s place at the top of a hierarchy of human cultures.

The law was one glory of the British Empire; antislavery was another.[4] The abolition of slavery in Britain’s West Indian colonies, in the Cape Colony, and in Mauritius on August 1st, 1834 was intended to bring the more than 800,000 enslaved people in the colonies out from slavery and into the sheltering arms of British justice. But for former slaves and their descendants, freedom was not autonomy.[5] This was no unintended consequence of the law, nor was it the result of unscrupulous administrators far from Westminster. Most Britons who supported emancipation presumed that the institution of slavery had prevented enslaved people from learning the value of wages; hard work and the accumulation of wealth would need to be taught. At the same time, the Emancipation Act forbade most of the tactics for negotiation that former slaves might have profited by in the new free-labor economy, including work slow-downs and strikes. In 1834, most of these forms of protest were illegal in Britain as well. However, the Emancipation Act added a racial edge to British labour laws through hazily-defined offences like “indolence” that were punished by magistrates and which were based on white observers’ perceptions of freedpeople’s affective states and attitudes toward wage work. All but the most radical white British supporters of the antislavery cause took it as a matter of fact that slavery had bred “indolence” into the bones of black workers. As slavery ended in much of the British colonial empire, the criminalization of black freedom began.

From August 2nd to August 4th 1834, days after the abolition of slavery, Thomas Coleman, the senior “special magistrate” in Trinity Parish, British Guiana, made a tour of the local sugar plantations: Richmond, Belle Alliance, and Lima. Coleman was one of a few hundred special magistrates recruited under the 1833 Emancipation Act, with a special mandate to enforce the law and mediate disputes between former slaves and former slave-owners. One of the first tasks that special magistrates like Coleman were given was to explain the terms of the Act to newly-emancipated people. This was a difficult task, because the Act stipulated that former slaves would become “apprentices,” legally required to continue to work without pay for the people who had once claimed to own them. At Richmond, Belle Alliance, and Lima, Coleman spent two hours explaining the law, “and referred to the Act of Parliament to prove to them that it was the King’s law, which some of them seemed to doubt.”[6]

John Duke, the young Rector of Trinity Parish, remembered being visited by two other special magistrates, Austin and McCoy, who briefed him on what to tell his congregation about emancipation. A few of the apprentices from Belle Alliance, still convinced that Coleman had lied to them, visited Duke. The preacher remembered that the apprentices told him “the King had freed them.” Duke claimed that he did not make “any remark to them touching a sum of money paid by the people of England for them.”[7] The apprentices had reason to be nonplussed. Under the terms of the Emancipation Act, the British government had established a fund of £20 million to compensate slave-owners for their lost human capital. News from Britain travelled quickly on the plantations, and the new apprentices imagined that the £20 million had purchased their freedom. But the £20 million – raised through loans, a colossal sum, more than a third of the government’s annual budget – was compensation to slave-owners, not a manumission fund.[8]

Moreover, the £20 million did not represent the full value of the capital tied up in human bodies in Britain’s sugar industry. The law that ended slavery in Britain’s colonies sang a hymn to the sanctity of property. It was designed to protect the sugar industry, and to make dispossessed slave-owners whole. The second part of the compensation package for slave-owners was apprenticeship itself. To pay off the rest of the value of their labor, freedpeople who had worked in the fields under slavery would work without pay for forty and a half hours a week until 1840. Enslaved people who did skilled work, or who had worked as domestic servants, would be apprenticed until 1838. In the fields, plantation work usually lasted from dawn to dusk, six days a week. In “crop time,” when the sugarcanes were harvested and processed, most plantations kept the sugar mills and boilers running twenty-fours a day. Near the Equator daylight lasts for roughly twelve hours, with little variation through the year. So by the reckoning of the Emancipation Act, every apprentice now had a little over thirty hours of labour – of “free time” – to sell every week, or to sell to cover crop time.[9]

The Emancipation Act, which the special magistrates enforced reached back into the legal history of England and Scotland and revived the category of “praedial labor” to describe the agricultural work done by enslaved field-workers. Domestics and skilled workers became “non-praedial” workers. Black workers were, legally speaking, from another time and subject to a different set of laws until Britain brought them back into the present. It is not surprising that twenty-nine of the thirty-one Members of Parliaments who owned plantations in the Caribbean voted in favour of the Emancipation Act.[10] However, it is also important to remember that apprenticeship was not contrary to the principles of imperial antislavery or mainstream British abolitionism. Many abolitionists in Britain loathed apprenticeship, but they loathed it because they it seemed unfit for purpose. All but the most radical abolitionists advocated gradual emancipation. British advocates for immediate emancipation were often women, like the philanthropist and writer Elizabeth Heyrick, whose arguments mainline abolitionist found easy to dismiss.[11] The leaders of Parliamentary and public antislavery assumed that slavery had made enslaved people economically incompetent and had pushed them far down the hierarchy of civilization. They agreed that freedpeople ought to be brought slowly into the economic present. They agreed that former slaves would need to be taught how to be free – apprenticeship was anathema to many abolitionists largely because it seemed like a bad education. Abolitionists like Joseph Sturge who advocated for immediate emancipation and complete wage labor, rather than apprenticeship, imagined British missionaries – rather than magistrates – as the appropriate people to teach freedpeople the meaning of freedom.[12]

Special magistrates like Thomas Coleman presided over a remarkable moment in the criminalization of blackness in Britain’s empire. Under the slave codes of most of Britain’s colonies, overseers and planters had vast arbitrary power to punish enslaved people for any infraction, real or imagined. The slave codes focused on punishing murders and other various serious forms of physical violence committed by blacks against whites, and on punishing runaways and enslaved people who conspired to rebel against planters. But after emancipation, apprentices suddenly had legal personality, and could be prosecuted for all of the crimes on the statute book. Moreover, under the post-emancipation regime, and particularly in the hands of the special magistrates, apprentices found that the kinds of infractions that might have resulted in a blow from a driver or overseer were now crimes that were subject to official punishment. Special magistrates had the responsibility to punish apprentices who did not work at an appropriate rate with the loss of control over some or all of their free hours. The special magistrates were also responsible for figuring out what an appropriate rate of work ought to be. Special magistrates embodied both the policing and discipline of oppressed people, but also their bureaucratization. As they defined new crimes and new punishments, they were creating the very categories of “civilized” life that they were mandated to police. The Emancipation Act created new crimes, like “indolence” and “neglect of work.” The Act also defined a new set of crimes against the state, including riot and marronage but also new offenses for apprentices, like “the desertion of helpless children” and “desertion of the Colonies to which they belong.”[13]

Back in Trinity Parish, British Guiana, in his sermon on the Sunday of the week of emancipation, the parson John Duke preached from the Book of John, Chapter 8: “If the Son therefore shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed.”[14] The apprentices who heard the sermon felt that they understood what that meant. At Coffee Grove, another plantation in the parish, apprentices told the special magistrate Thomas Coleman that they would only work for wages, and that they were only willing to work without pay for two hours a day in order to pay for provisions from the plantation stores and to cover the rent for their houses and vegetable gardens, “that they thought was ample.”[15] The colonies that were amalgamated into British Guiana, Berbice, Demerara, and Essequibo, had once belonged to the Netherlands. The colony’s slave-owners included Dutch and French, as well as British planters. The colony, unlike Jamaica, Barbados and other “old colonies” in the Caribbean was governed directly by the Crown, rather than by a local legislative assembly, and the colony’s slave code was an amalgam of British and Dutch laws. Guiana, unlike the older island colonies, was also plump with uncultivated land and its sugar plantations were much more profitable. The Emancipation Act took this into account. Under the Act, the labor and capital value of enslaved people in British Guiana and other newer colonies like Trinidad was rated higher than in the older colonies. Labor was more valuable in Trinity Parish, and consequently it was particularly important that black apprentices work for wages with as little negotiation as possible.

Richmond Plantation was owned by Charles Bean. Bean, unlike many British slave-owners, who chose to live in Britain and receive the profits of their plantation as annuities, resided on his plantation. On August 9th, 1834, an apprentice from Richmond named Damon, along with a group of other unarmed apprentices, raised a flag at Trinity churchyard. The flag was white, with a black St. Andrew’s cross through it – a wide black “x” across a white field.[16] More and more apprentices gathered in the churchyard, convinced that Bean and other slave-owners were trying to hijack their new freedom. They simply did not believe that apprenticeship could possibly be the freedom they imagined, or the freedom that news from Britain suggested had been promised to them. They demanded to see the Governor, and refused to return to work expect for wages. They clearly understood and valued wage work, but they did not understand that, in the post-abolition British Empire, their right to negotiate wages was neutered both by overarching laws against “combinations,” but also by laws specific to black freedpeople. When Bean visited, one of the apprentices made a fist at him, “threatening me, saying that I had made the law to injure them, ‘to cut them,’ I think the expression was.”[17] By Sunday morning, the preacher John Duke guessed that there were as many as five hundred apprentices packed into the churchyard at any given time, and as many as a thousand in total. Duke, Bean and the special magistrates all demanded that the apprentices leave the churchyard. They refused. The planters demanded that the Governor, Sir James Carmichael-Smyth, impose martial law. He refused, but he did assemble a group of soldiers and visited Trinity churchyard in person to explain that apprenticeship was not a cruel planters’ joke, but imperial law.[18] The apprentices dispersed.

Damon was executed. Four more apprentices were transported – it isn’t clear to where. There was a tradition in Britain’s slave colonies of sending away enslaved people who had been convicted of a crime to be sold in a colony belonging to another empire. It is possible that the four transported apprenticed ended up enslaved in Cuba or Puerto Rico.[19] Thirty-two more were sentenced to be flogged or imprisoned, but the Governor offered them a pardon. Exemplary punishment was one thing, but enough apprentices had joined the protest that the public whipping of thirty people might lead to rioting. At sentencing, before the Supreme Court of Demerara and Essequibo, the Chief Justice declared that the apprentices were guilty of having “illegally declared and asserted and insisted that they were free.”[20] But what they were really guilty of was not knowing what black freedom was supposed to mean in the British Empire. The judge harangued the defendants for assuming that “freedom” meant “that that they were liberated and exempted from being restrained and compelled by law to the performance of the work and labour which by the law they… were bound to do and perform.” Thomas Spring Rice, at the time Secretary of State for War and the Colonies in Britain, was pleased with the outcome of the case. He wrote to Governor Carmichael-Smyth, that he felt “sincere satisfaction … that the quantum of labour required by law is now regularly performed by the labourers all over the Colony.” He noted, though, that the many wealthy former slave-owners in Britain were anxious to hear about Damon’s occupation of the church-yard. “The mode,” Spring Rice wrote, “adopted of making signals in order to bring the negro population into combined action, exhibit a very formidable state of concert, and should on conviction be followed by severe punishments.”[21]

Apprenticeship was short-lived. In 1838, the intransigence of the legislatures of the old slave colonies, particularly Jamaica, led to the collapse of the system. Antislavery activists in Britain called apprenticeship a continuation of slavery by another name, and planters called it an unfair burden on their plantations. Consequently, the tendency among many historians has been to treat apprenticeship – and special magistracy – as an aberration.[22] But the special magistrates continued to work in the former slave colonies after the end of apprenticeship, and the essential idea that black people in the empire needed a different set of rules governing their economic lives survived. The waves of British missionaries who descended on the former slave colonies in the 1830s shared the same assumptions about black incapacity as former slave-owners did. But where former slave-owners thought corporal punishment would force black workers to accept the logic of wages and the discipline of capitalism, missionaries aimed to show their congregations that wage-work was virtuous.

The special magistrates did not invent imperial racism, or contempt for black people in the British Empire. In the same 1824 speech to the House of Commons in which he framed his plans for gradual emancipation, a group of reforms that became known as “Canning’s Resolutions,” George Canning compared black freedom to Frankenstein’s monster, “the splendid fiction of a recent romance,” a creature “possessing the form and strength of a man, but the intellect only of a child.”[23] The special magistrates didn’t create the racist assumptions driving Canning’s program of gradual emancipation, but they were charged with building everyday rules of wage work and labour discipline that embodied it in practice and that constantly reinforced and affirmed it. The British justice system was one of Britain’s most valued exports, one of the gifts that the British Empire believed it gave to the people it ruled. In Guiana in 1834, Damon was hanged for insisting on a version of black freedom that was prosecuted as a crime against post-emancipation capitalism. Charles Bean, the man who had once claimed to own him, would later claim more than £16,800 from the Slave Compensation Commission.[24]

Padraic X. Scanlan is Assistant Professor in the Department of International History at the London School of Economics and Political Science. He is the author of Freedom’s Debtors: British Antislavery in Sierra Leone in the Age of Revolution(Yale University Press, 2017), which was awarded the 2018 Wallace K. Ferguson Prize by the Canadian Historical Association and the 2018 James A. Rawley Prize by the American Historical Association.

References:

[1] On the eighteenth-century criminal law, see Douglas Hay, “England, 1562-1875: The Law and Its Uses,” in Masters, Servants, and Magistrates in Britain and the Empire, 1562-1955, ed. Douglas Hay and Paul Craven (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 59–116; Douglas Hay et al., Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England, Revised (London: Verso, 2011); Peter Linebaugh, The London Hanged: Crime And Civil Society In The Eighteenth Century, 2nd edition (London: Verso, 2006).

[2] Jordanna Bailkin, “The Boot and the Spleen: When Was Murder Possible in British India?,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 48, no. 02 (April 2006): 462–493.

[3] Catherine L. Evans, “Heart of Ice: Indigenous Defendants and Colonial Law in the Canadian North-West,” Law and History Review 36, no. 2 (May 2018): 199–234.

[4] Seymour Drescher, “Whose Abolition? Popular Pressure and the Ending of the British Slave Trade,” Past & Present, no. 143 (May 1994): 136–66; Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation, 1707-1837 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 350–60.

[5] On conflicts between freedpeople and colonial officials over the meaning of emancipation, see Thomas C. Holt, The Problem of Freedom: Race, Labor, and Politics in Jamaica and Britain, 1832-1938 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992); Thomas C. Holt, “The Essence of the Contract: The Articulation of Race, Gender, and Political Economy in British Emancipation Policy, 1838-1866,” in Beyond Slavery: Explorations of Race, Labor and Citizenship in Postemancipation Societies, by Frederick Cooper, Thomas C. Holt, and Rebecca J. Scott (University of North Carolina Press, 2000), 33–59; Diana Paton, “Punishment, Crime, and the Bodies of Slaves in Eighteenth-Century Jamaica,” Journal of Social History 34, no. 4 (June 1, 2001): 923–54; Diana Paton, No Bond but the Law: Punishment, Race, and Gender in Jamaican State Formation, 1780–1870 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2004); Melanie J. Newton, The Children of Africa in the Colonies: Free People of Color in Barbados in the Age of Emancipation (Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 2008); Natasha Lightfoot, Troubling Freedom: Antigua and the Aftermath of British Emancipation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

[6] Testimony of Thomas Coleman, Enclosure No. 4, British Guiana Despatch No. 4, 1835 (278-I) Papers Presented to Parliament, by His Majesty’s Command, in Explanation of the Measures Adopted by His Majesty’s Government, for Giving Effect to the Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies, Part I, Accounts and Papers (London: Great Britain, House of Commons, 1835), 201.

[7] Testimony of John Halloway Duke, Enclosure No. 4, British Guiana Despatch No. 4, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 195.

[8] On the financial history of emancipation and compensation, see Nicholas Draper, The Price of Emancipation: Slave-Ownership, Compensation and British Society at the End of Slavery (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[9] On the broad contours of the Emancipation Act and sugar-plantation labour, see J. R. Ward, British West Indian Slavery, 1750-1834: The Process of Amelioration (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988); William A. Green, British Slave Emancipation: The Sugar Colonies and the Great Experiment, 1830-1865, 1st paperback edition (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991); W.L. Burn, Emancipation and Apprenticeship in the British West Indies (London: Jonathan Cape, 1937).

[10] Robin Blackburn, The Overthrow of Colonial Slavery 1776-1848, 2nd edition (London: Verso, 2011), 457.

[11] See Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate, Not Gradual Abolition, Or, An Inquiry Into the Shortest, Safest, and Most Effectual Means of Getting Rid of West Indian Slavery (London: Hatchard, 1824).

[12] On Sturge and the Baptists in Jamaica, see Catherine Hall, Civilising Subjects: Colony and Metropole in the English Imagination, 1830-1867 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002).

[13] Circular Despatch, Lord Stanley to the Governors of HM Colonial Possessions having Local Legislatures, 19 October 1833, 1835 (177) Abolition of Slavery. Papers in Explanation of the Measures Adopted by His Majesty’s Government, for Giving Effect to the Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies. Part I. Jamaica. 1833-1835., Accounts and Papers (London: Great Britain, House of Commons, 1835), 22.

[14] Testimony of John Halloway Duke, Enclosure No. 4, British Guiana Despatch No. 4, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 197.

[15] Testimony of Thomas Coleman, Enclosure No. 4, British Guiana Despatch No. 4, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 201.

[16] Eleventh Criminal Session: Extract from the Criminal Note Book of His Honour the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Demerara and Essequibo, 23 September 1834, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 188.

[17] Testimony of Charles Bean, Enclosure No. 4, British Guiana Despatch No. 41835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 205.

[18] Sir James Carmichael-Smyth to Thomas Spring Rice, 9 August 1834, British Guiana Despatch No. 114, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 157.

[19] See John Savage, “Unwanted Slaves: The Punishment of Transportation and the Making of Legal Subjects in Early Nineteenth-Century Martinique,” Citizenship Studies 10, no. 1 (February 1, 2006): 35–53; Philip J. Schwarz, “The Transportation of Slaves from Virginia, 1801–1865,” Slavery & Abolition 7, no. 3 (December 1986): 215–40.

[20] Sentencing of Damon et al., Enclosure No. 4, British Guiana Despatch No. 4, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 198.

[21] Spring Rice to Carmichael-Smyth, 1 November 1834, Despatch No. 2, 1835 (278-I) Abolition of Slavery, Papers in Explanation, Part I, 181.

[22] Green, British Slave Emancipation, 136–134; Holt, Problem of Freedom, 57–60; Hall, Civilising Subjects, 115; Burn, Emancipation and Apprenticeship in the British West Indies, 196–266; William Law Mathieson, British Slavery and Its Abolition, 1823-1838 (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1926), 228–56; Paton, No Bond but the Law, 53–82.

[23] Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 15 March 1824, “Amelioration of the Slave Population in the West Indies,” Parliamentary Debates: Forming a Continuation of the Work Entitled the Parliamentary History of England from the Earliest Period to the Year 1803, vol. 10 (London, 1824), cc. 1103.

[24] See British Guiana Claim 2290 (Richmond), Centre for the Study of the Legacies of British Slave-ownership (UCL), “Legacies of British Slave-Ownership,” 2018.

Published on November 8, 2018.