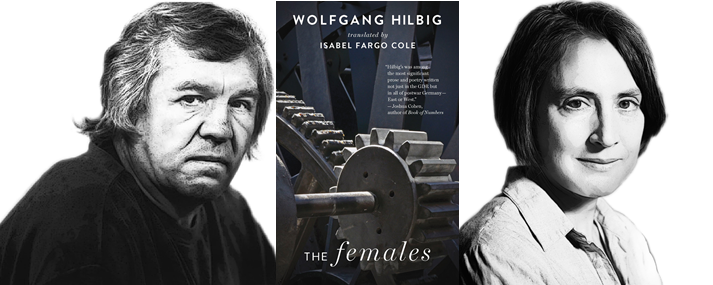

Translated from the German by Isabel Fargo Cole.

It was hot, a damp hot hell, sweat emerged from all my pores. I began excreting smells, how strange, as though something within me were starting to mold, an extraordinary fromage, as though I smelled of my eyeballs, which bulged and welled with what seemed a sort of slime, a turbidity likely rising up from my loins, a twinge from the groin that brushed my heart, stinging; it dug slowly into my brain, but I hadn’t felt its onset. I’d become unfit for the tool shop, and was sent down to the basement to arrange steel casting molds and cutting tools on the shelves, neatly and cleanly, as I was told. Cleanly—but wherever my moist hands touched the molds, rust appeared a few days later. During inspections these spots earned me reprimands, and I began to brush the molds with oil, oil that sizzled on the brown surfaces, emitting a burned smell; but stronger by far was the smell I myself emitted. Great flaking scabs infested my elbows, white eruptions that smelled of sour milk, and I hunkered inert at the table in the humid basement, not even shocked but dismayed to see all my fears confirmed with such absurd consistency, all my thoughts turned almost purposefully into stagnant poison. Daily, and later several times a day, I masturbated in the basement, treading that shimmering spittle across the concrete floor; there was not the slightest reason for these abuses, not even a physical urge; you swine, I told myself, hurry up, or some-one will walk in on you. But it took me longer and longer; I whipped myself into increasingly harried states, but the twinge from my hips never faded; meanwhile I went on sweating, outpourings that paralyzed and weakened me, my member drained my last remaining strength, and when I shook myself with my weary fist I spluttered out nothing but a dry, painful cough. I went on sweating, though the windowless basement, lit by a single light bulb, seemed cooler than the air of those three summer months smoldering outside the factory.

A bit more light fell through a square grate in one corner of the ceiling; it came from the pressing shop above the basement, where the machines pounded away. Much earlier, when this factory had produced munitions, using prisoners from the camp directly attached to it, valuable metal lings had been dumped into the basement through this grate. Now it served as the hatchway for a mechanical hoist that lowered the often extremely heavy molds—which I dismantled, cleaned, reassembled, and gave labels and numbers—from the pressing shop. But no one would open the grating for me; left open for hours unattended, they said, it would be too dangerous for the women who worked in the pressing shop and had to walk back and forth past it. I dragged the molds down to the basement via circuitous routes and steep stairways, which took days at a time. Following these bouts, I wouldn’t touch a thing at first; I’d sit still at the table, tensely attending to the tremble of my musculature, the quiver of my lungs, signals that quieted only gradually; the tools’ sharp edges had chafed my hips and sweat burned fiercely in the wounds, which seemed to sink deep into my body, as though my nerve cords were injured, the currents of my senses severed.

And the pressing shop was where the females worked—rough the grating above me, damp, smoldering heat flooded down with steady force. I sat on a chair beneath the grate amid this hot tide, hidden in semidarkness, several bottles of beer by my chair; when I drank, the beer seemed to gush instantly from all my pores, lukewarm, not even changing temperature inside my body. It was a ceaseless strain—head constantly tilted back—to stare through the grate into the light, always hoping to see the women up there step across the bars. Sometimes I climbed onto the chair, almost touching the iron grid with my brow, to gain a narrow, densely crisscrossed view into the pressing shop; I could see the short stepladder, a bit more than a yard high, by which the women reached the capacious hopper of a mill that ground away with a terrible racket, reducing scraps of cooled plastic—left from the casting of coil-like radio parts in the presses—to granules enough for reuse.

From that vantage point I could see two or three women, the oldest and strongest, who were assigned to work the hand presses. Backs turned toward me, they sat on tall three-legged stools that swayed and seemed to squeak; due to the heat they dispensed with cushions, the mass of each gigantic behind completely swallowing the stool’s round wooden seat; like all the women in the shop, they wore nothing but thin brightly colored smocks, and when they thrust themselves upward to the presses’ long levers I saw that their smocks were hiked up, that they sat back down with parted legs, and that their knees finally tilted inward as their bare or clog-shod feet pressed down on the ends of the long, wide pedals to lock the molds in place; their behinds rose ten inches above the seat and for a moment their thighs seemed to slacken, their buttocks to sag, then tensing to utmost firmness, perhaps pressing intensely fragrant substances into the taut fabric of their smocks; the women—of whose upper bodies I could see only a narrow strip above the waist, since a crane track that crossed the hall spoiled much of my view—had seized in both fists the upward-tilting levers and brought them down by latching on with all their heavy bodies’ weight, doing this, I sensed, with deep sighs, as though a log had been split in their chests; the machine’s top part then sank down onto the firmly fixed jaws of the mold, discharging a portion of the boiling, steaming plastic; the women, remounting their seats, held down the phallus-like lever so that the plastic released from the nozzles could cool as their thighs gripped the seat’s hard surface; I knew that the women’s upper arms had stiffened to iron, that their shoulder muscles, shoulder blades, and clavicles had fused into one hard, armored form; then their fists, already drained of blood, let the levers spring back up to open the jaws and eject the two or three cooled coils from the molds’ laps. All this was the work of no more than thirty seconds. The women were paid by the piece, and the crew at the hand presses constantly changed, so that throughout the week I could watch nearly all the older women as they worked these machines—always women of similar stature, of similar heft and strength, all similarly dressed, with the damp fabric of their smocks stretched to breaking over the swells and bulges of their prodigious bodies—and often I saw them blur in the fumes of their effluvia, their backs’ brightly flowered expanses spilling into the shimmering air of those three summer months that, in the cloud-core of the pressing shop, were nothing but a seething stench of rubber and plastic. Under their stools I noticed big dark puddles; I speculated that they had formed from the women’s sweat or even their urine, but soon surmised resignedly that it was merely the worthless residue of the cooling water trickling from leaky joints in the molds, which the women, unresisting, allowed to bathe their legs.

Now and then men stepped lightly across the grating above my brow, the men from the tool shop, moving elegantly, wearing almost spotless uniforms, holding delicate, harmless tools; their job was to ensure that the machines ran smoothly, and quickly per- form minor repairs, strutting unperturbed through the racket, fanning themselves, chatting near the ventilators; none of them heeded the lewd, uncouth remarks the women yelled in their direction over the hiss of the presses, the pounding of the machinery, the howling of the mills, the crunch of the cutting tools, through the whole rhythmically gathering and splitting fabric of noise—remarks I heard clearly, but did not understand.

The women never crossed the grate. Rarely, unexpected and quick as a ash, they’d skim some little corner of my vision: alas, they passed in twos or threes without ever setting a clog on the iron lattice, their shadows barely flitting over me; for a fraction of a second I’d hear their voices, an incomprehensible, indistinguishable chatter; they were contourless cylinders of darkness, speechless silhouettes wafting across me; all I could see were the objects they carried, pressed to their hips: large, evidently heavy cardboard boxes which alone could be clearly discerned hovering over the grate. I wouldn’t see the women again until they stopped at the stepladder by the waste mill. This was the long-awaited moment when I’d press my brow, my face against the grate to see—to see one of the two women climb the stepladder to lean forward over the mill hopper, at which I’d fail to notice a third woman following the first two with a bucket in her hand. It was the moment when the hem of the smock worn by the forward-leaning woman on the ladder seemed to slip far up the reddened backs of her thighs, when the smock’s flimsy synthetic fabric seemed to blaze in the light of the nearby window, in that white-hot thrust of sunlight; the moment when the heavy, slightly gaping buttocks must be revealed instantly, as if through some trick of physics in an incalculable second, soon, instantly, exposing a point of in- visible darkness, the lightning-like moment when a hot drop of sun must in flame the nerves of the flesh that would be freed—I had no idea what I meant by that—and the moment in which the third woman following the other two indulged in a savage jest, doubtless repeated a hundred times over: with a mighty swing of her arms she tossed the contents of the bucket, five or six liters of cold clear water, in one sharp, perfectly calculated jerk of unthinkingly perfect aim, sending the water in a beeline through the burning air and under the smock of the woman on the ladder, right between the woman’s thighs, slapping the entire backside of the woman’s lower body, at which a shriek of amusement from the woman on the ladder immediately confirmed her most grateful acceptance—anticipated, but still startling—of the unerring bull’s-eye: oh what welcome coolness!; I saw nothing, I saw the surge of water rebound in spray; what I’d wanted to see was swamped, washed away and warped by water; as the water coursed to the ground, shot toward the grate and spilled into the basement through the iron lattice, I leaped from my chair to capture it with my cupped hands, which could not catch it, with my face, instantly spattered, with my nose, with my gaping mouth, as though I could grasp some trace—some barely perceptible bloom of femininity that might have been washed o and carried along, that, for all the rapidity of the incident, must have infiltrated the water a tiny bit—grasp it, devour it, retain it in a single pore of my skin, even if I never noticed. Nothing met my lips but dust washed from the floor, nothing clung to my hands but the fouled water’s gasoline smell, all I had in my nostrils was the burned-rubber smell, the inhuman smell of plastic which, cooled for a few seconds by the water, now tasted even more vivid and more obscene.

I had gradually begun to transform into a sickness. Like all things I produced, this transformation was utterly excessive; an agony not quite human, it was no longer that of an animal, either. It led to my dis- missal from the factory, though the details aren’t worth mentioning; I lived in circumstances in which the symptoms outweighed the causes, or, rather, the causes kept transforming into the symptoms; I hid in my apartment by day and went out only at night, in the dark, roaming the town’s deserted streets, soliloquizing, holding rousing speeches to myself, sweating, covered with milky green pustules. A terrible thing had occurred, the worst thing ever to have happened since I’d learned to contemplate life from the outside, since I’d learned to use life to manufacture descriptions which made an inner life possible for me. A terrible thing, yet I was supposed to call it beauty. If I’d managed anything like it before…I’d always doubted I could…the discrepancy this time was most stark, it was appalling, nothing about the event could be transformed into a beautiful idea for my inner life. Earlier, I hadn’t minded making lth glitter; in earlier writings that I’d submitted for publication—that I’d submitted…I grinned…to pressure, or removed from myself in some other way, or that had been removed from me—the horrors had at least been palatable; I’d cloaked them in cheap mystication, and though I’d never been able to establish them on the market, at least their sale was being discussed. Oh, these lovely prisons—in words like these I’d described the trash cans on the street, described them not quite as useful, but as reflectors of magical moonlight, I’d made them gleam in the sun like big tins, I’d called their glitter silver.

But now something had happened that I couldn’t so easily bend to my will, not any sort of defilement, but rather a lack of richness, an especially painful loss; the town seemed to have suddenly shed a certain part of its makeup; at first I thought it had shed one of its smells. e insanity must have begun the day I was let go from the factory; since that day, at least, I’d felt the lack of some particular thing: venturing out in the evening I struggled for air, it was as though the air were drained of a special aroma, an aroma I needed in order to live. I sought the cause of this sensation; then came a suspicion that grew stronger, and soon I roamed for days at a time just to see how right I was, for nights at a time just to confirm my hideous suspicion: all the females had vanished from town. It was no help at all to sense I was possessed by an obsession, in my overpotent head a cascade of letters blazed: all the females of the species had vanished from town, and with them had fled every trace of femininity. Not only that, I felt that even feminine nouns had fallen out of use; I thought I suddenly noticed people in town referring to trash cans as der Kübel instead of die Tonne. When I saw those trash cans from afar, set up in long rows along the curbs that summer—something unlikely to change, as the trash collection service was still more dysfunctional then than in the winter—at first I’d think a line of unshapely females was loitering there, dully iridescent in the bluish streetlights, and I’d hurry toward them. I’d realize they were just the trash cans I saw every night, from their gaping orifices hung rubbish that looked hairy, that had some indefinable evil about it. I went so far as to impetuously embrace a trash can and lift it from the ground, as one sometimes does in the first ardent moments of reunion—that was possible at this time of year, when the containers generally held nothing but rotten fruit and crumpled paper, perhaps some old clothes—and confirmed that what I embraced was a cool, ugly bin of smeary metal that repelled me; I set it back on the ground with a crash and was surrounded by flies that had been resting in the rubbish of the containers and suddenly seemed to regard me as a better place, but then flew away in outrage when I snatched at them.

Wolfgang Hilbig (1941–2007) was one of the major German writers to emerge in the postwar era. Though raised in East Germany, he proved so troublesome to the authorities that in 1985 he was granted permission to emigrate to the West. The author of more than twenty books, he received virtually all of Germany’s major literary prizes, capped by the 2002 Georg Büchner Prize, Germany’s highest literary honor.

Isabel Fargo Cole’s translations include The Sleep of the Righteous, by Wolfgang Hilbig (Two Lines Press); Boys and Murderers by Hermann Ungar (Twisted Spoon Press, 2006); All the Roads Are Open by Annemarie Schwarzenbach (Seagull Books, 2011); and The Jew Car by Franz Fühmann (Seagull Books, 2013).

This excerpt from Old Rendering Plant is published by permission of Two Lines Press. Translation copyright © 2018 by Isabel Fargo Cole.

Published on October 2, 2018.