Countries in the Global North have and continue to maintain political borders by employing a rhetoric of protecting the nation from racialized outsiders. Like Italy, Spain’s geographical proximity to Africa has put Spain on the forefront of this debate as migrants not only enter Spain, but also travel to other countries in the European Union. Silvia Bermúdez’s latest book Rocking the Boat offers a timely look into how musical narratives produced in Spain serve as cultural responses to legislative measures to secure entry into Europe, and portray the experiences of transnational migrants from the early 1980s to 2011. Drawing on the concept of “Fortress Europe,” first used during the Second World War to refer to defending Europe from outsiders (Seaton 1981), Bermúdez applies the term to the dangerous process of migrants attempting to enter the EU via its southern boundaries. By placing her close reading of song lyrics and melodies at the forefront of her analysis, Bermúdez skillfully brings together contemporary issues in the fields of Iberian studies, Migration studies, and musicology. This three-pronged approach allows Bermúdez to explore the sociocultural responses to measures to secure Fortress Europe within the context of Spain’s 1985 Immigration Law and the current economic and social crisis.

Racial anxieties, both past and present, frame the book by way of musical responses to migration. Rocking the Boat opens with a reference to W.E.B. Du Bois’s 1900 lecture regarding “the problem of the color line” (3) to give historical depth to her study of how musicians approach race and racism within the geopolitical context of transnational migration. Bermúdez argues that one must take into consideration how the racialization of migrants in Europe has emerged through a decades-long process of migration from the Global South and East to the Global North. The musical analysis brings together insights from multiple disciplines to trace the discourse of migration during the period studied in depth. While the book prioritizes studying the music itself, Bermúdez does enter into conversation with Theodor Adorno’s 1990 essay “On Popular Music,” by considering the role of enjoyment in social identity formation related to transnational capitalism and the consumption of music and, thus, transatlantic success. It is this success that forms the basis for Bermúdez’s musical selections. The musical groups and cantautores (singer-songwriters) studied mostly choose undocumented migrants as the subject for their songs and they span a variety of musical genres and hybridizations. Despite the emphasis on Madrid and the predominance of Castilian Spanish, this song list also includes “Oveja negra” by the Basque group Barricada, Joan Manuel Serrat’s “Salam Rashid” in Catalan, and “A ba’ele” (“The foreigners”) by Las Hijas del Sol includes some lyrics in Bubi. The four chapters following the introduction chronologically examine how migration has entered Spain’s cultural imaginary.

Bermúdez successfully balances the transnational context of her book with a commitment to exploring this context in the musical analysis that comprises the bulk of Rocking the Boat. The scope of the book and the variety of experiences that it encapsulates, from representations of Muslim migrants to homages to Lucrecia Pérez, a Dominican migrant murdered in Madrid, are both specific to the Iberian context and broad enough to speak to the larger European and transnational contexts. The musical analysis running through the book provides ample space for readers to trace how musicians’ attitudes about migration have changed in line with Spain’s political and social responses to undocumented migrants and larger movements of transnational capitalism. Chapter 1 centers on Radio Futura, Mecano, and the cantautor Joan Manuel Serrat, all very successful musicians during the Movida madrileña, the distinct musical scene that emerged in Madrid during the transition to democracy beginning in the late 1970s and continuing through the early 1980s. Bermúdez posits that the songs studied in this chapter represent the beginning of a trend in which artists “participate in the articulation of a Spanish racial imagination vis-à-vis migration” (63). It is in this first chapter that Bermúdez stakes a claim for analyzing the songs as soundtexts through a process of close attention to lyrics and melodic analysis. One should note that the melodic analysis only appears in chapter 1 courtesy of the assistance of musicologist Eduardo Viñuela, and David Thurmaier provides the chords for “Disculpe el Señor” in chapter 2. Given readers’ varying points of entry into Rocking the Boat, a more sustained discussion regarding the social changes in Spain during the transition to democracy would have been helpful, particularly with respect to Helen Graham’s 1995 article cited in the introduction about the role of music during the dictatorship.

Chapters 2 and 3 feature the 1990s and how the discourse about migration centered on race. Bermúdez tracks this changing discourse through the ways that songs articulate interactions with and the experiences of migrants, thus illuminating cultural responses to the political rhetoric surrounding migration in Spain and the EU at large. This micro to macro approach proves beneficial for providing evidence for how these artists bring awareness to migrant issues. Bermúdez tackles the problematic representations of the migrant-Other in songs like Pedro Guerra’s “Contamíname” in chapter 2, and in chapter 3 migrants speak to their own subjectivity as postcolonial migrant subjects in the case of the Equatoguinean group Las Hijas del Sol. The police brutality surrounding Lucrecia Pérez’s murder highlighted in several songs as well as the aunt and niece duo Las Hijas del Sol would lend themselves to discussing the intersection of race and gender, yet many of the popular artists studied are male. While Bermúdez brings forth excellent insights in her close reading of lyrics and includes a thorough selection of songs, she could have spent more time analyzing the individual songs. Nevertheless, Bermúdez guides readers to identify the many thematic commonalities and allusions to contemporary issues among the songs studied.

Chapter 4 takes a look at identity politics, artists’ social consciousness, and the hybridization of musical genres in Spain’s twenty-first century musical landscapes. Bermúdez informs readers that singers have started using hybrid genres like Concha Buika’s flamenco fusión to make listeners aware of and question the “epistemic violence exerted in the defense of the motherland” (137). Bermúdez informs readers that Buika’s own identity as a second-generation Spanish black woman who grew up on the island of Mallorca is central to the title of her song “New Afro Spanish Generation” from her 2005 album Buika. Bermúdez connects Buika’s process of mixing salsa and flamenco in the song to the artist rethinking musical, national, and racial identities. More elaboration on the production of the music studied in this chapter as it relates to the hybridization of genres would be beneficial here. Bermúdez’s use of definitions and theoretical insights is solid overall, although her claims for twenty-first century mestizaje and convivencia in this chapter remain somewhat tenuous without more direct comparisons to how Spain’s colonial history in Latin America feeds into current musical trends. With a new generation of artists who have upheld the centrality of race in contemporary Spain, the chapter opens up possibilities for future scholarship as these artists continue to produce music. I consider Rocking the Boat timely at a moment when Pedro Sánchez, the new Prime Minister of Spain and general secretary of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE), begins making agreements with other EU leaders on the migrant crisis while inflammatory racist rhetoric against migrants continues to appear throughout the Global North.

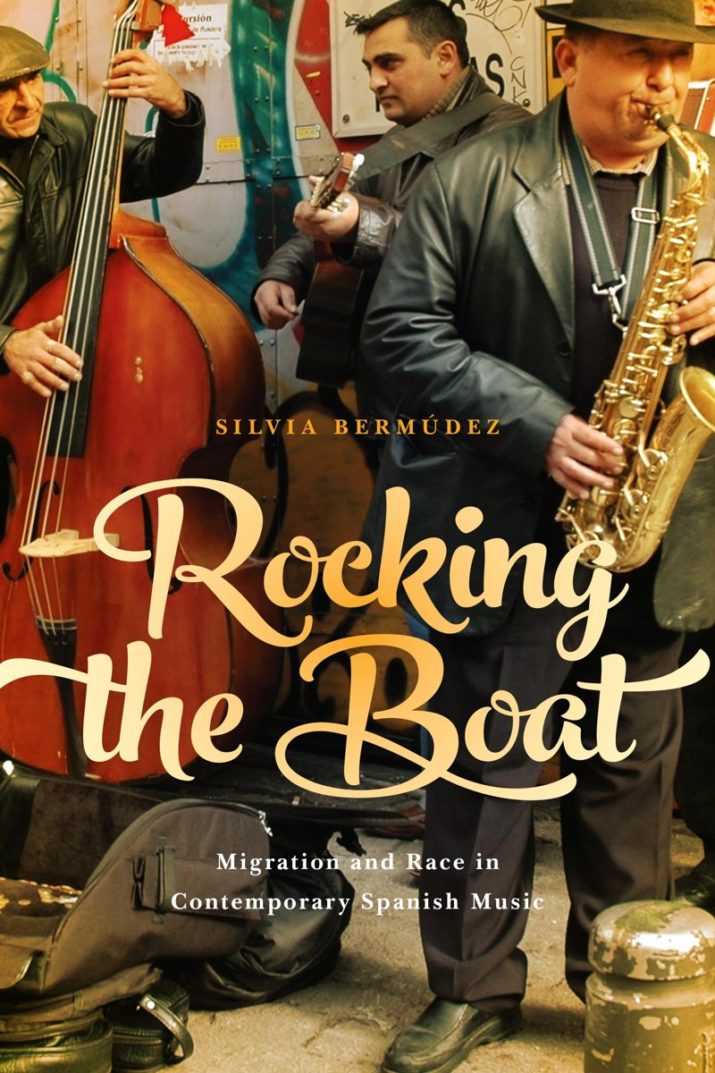

Bermúdez’s thorough close reading and clear prose make Rocking the Boat a good selection for undergraduate seminars and graduate course syllabi, and Hispanists and music specialists will also appreciate her multidisciplinary approach. Thanks to her training in Spanish literature and culture, Bermúdez shows a deep engagement to the texts studied that provides readers with an in-depth awareness of how Spain’s contemporary musical landscapes have formed. This emphasis on close reading means that readers should already be familiar with Spain’s transition to democracy and present migration debate, although the book offers many contextual signposts for those who are not specialists. Compared to related multidisciplinary works such as Frances Aparicio and Cándida Jáquez’s edited volume Musical Migrations: Transnationalism and Cultural Hybridity in Latin/o America, Rocking the Boat focuses more on racialized representations of migrants in music than the lived experiences of the artists and the interactions between migrant and resident communities in Spain. The few images in the book help bolster her argument about how migrants have disrupted sites emblematic of Spain’s national identity, helping to bridge the gap between the songs and lived experiences. The brief summaries of Spanish politics during each decade studied, translations of Spanish song lyrics reproduced in the text, and URLs to artists’ websites and other pertinent contextual information all allow for an engaging and accessible reading experience.

Reviewed by Angela Acosta, The Ohio State University

Rocking the Boat: Migration and Race in Contemporary Spanish Music

By Silvia Bermúdez

Publisher: University of Toronto Press

Hardcover / 183 pages / 2018

ISBN: 978-1-4426-4852-4

To read more book reviews click here.

Published on October 2, 2018.

Click here for our special feature on Beyond Eurafrica: Encounters in a Globalized World.