Making Meaning in a Global Art Market: Presentations of European Artworks by Chinese and Arab “Supercollectors”

This article is funded by the European Studies Undergraduate Paper Prize, awarded by the Council for European Studies.

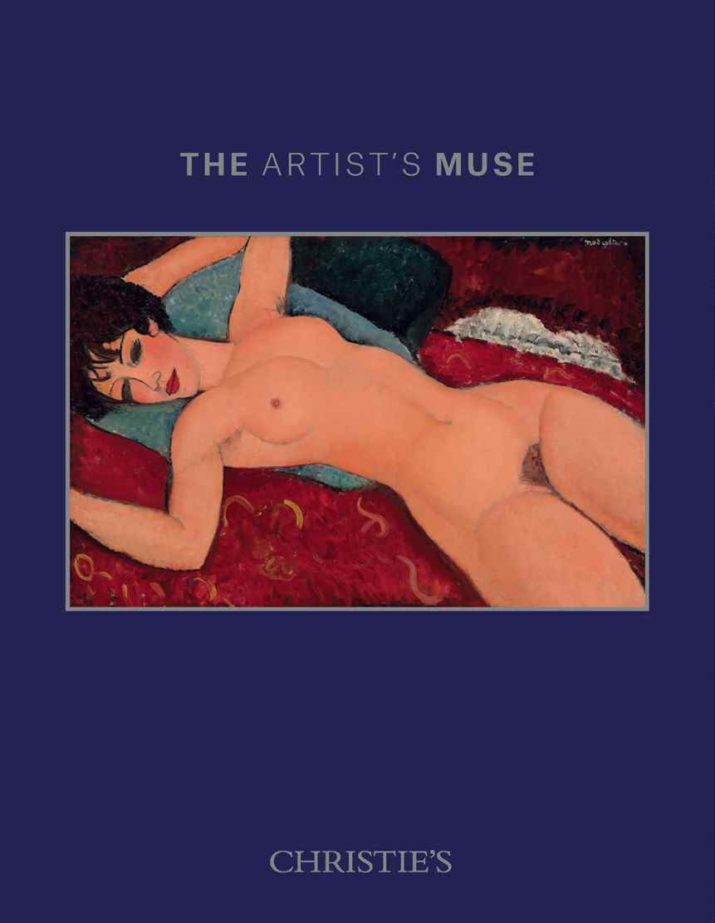

In 2014, the Chinese art collector Liu Yiqian acquired a Qing dynasty porcelain teacup for $36 million. After buying the cup at a Sotheby’s Hong Kong auction, he used it to drink tea and had himself photographed in the act (see figure 1.1). Afterwards, he explained: “Emperor Qianlong has used it, now I’ve used it…I just wanted to see how it felt.”[1] One year later, the same “taxi driver turned billionaire art collector” bought Nu Couché by Amedeo Modigliani for $170.4 million (see figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1 A photograph of Liu Yiqian drinking a Qing Dynasty teacup, taken by Sotheby’s.[2]

Figure 1.2 Nu Couché, a 1917 painting by Amadeo Modigliani, featured on the cover of a 2015 Christie’s auction catalogue. The painting was acquired by Liu Yiqian.[3]

While many collectors shy away from the publicity, Liu was quick to associate himself with the sale and its price, a new record for the artist. According to Liu, he made the purchase for his nation: “It will be a good opportunity for Chinese art lovers to see good artworks without having to leave the country.”[4] Through acquisitions like these, Liu Yiqian, along with his wife, Wang Wei, have become two of the most visible and publicized blue-chip art collectors in China.[5] They exhibit their collection in the Long Museum, a private museum funded and managed by the couple, with separate locations on government land in Shanghai and Chongqing. The Long museum has also featured work by European artists, both past and present, like Rembrandt and Olafur Eliasson.[6]

With a history of breaking price records, a growing list of art-world connections, and stated ambitions to grow the Long Museum into an institution like MoMA and the Guggenheim,[7] Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei are no ordinary art collectors; among followers of the art market, they are called “supercollectors.” Over the last ten years, new supercollectors have appeared in the art world’s “emerging markets,” namely China and the Middle East. They share characteristics with their European counterparts like François Pinault; beyond their collection sizes and private museums, they distinguish themselves from conventional collectors with their positions on the boards of institutions like the Tate Modern and their close relationships with artists, gallerists, and auctioneers. Together, they have helped turn China and the Middle East into major centers of the global circulation of fine art. In 2015, collectors from these two regions together accounted for roughly one third of sales among global auction houses, up from less than one tenth in 2005.[8]

Yet their practices certainly do not go uncontested. Liu Yiqian and Wang Wei encounter much criticism for the selection and treatment of their collection. Critics—most of whom are Western—claim that the couple lacks the knowledge to make informed choices and instead simply purchase whatever appears on the cover of auction catalogues.[9] As they depict it, Liu and Wang mismanage their museum, failing to invest enough resources in security, museum administration, and proper displays. According to one curator, “They are lacking in the absolute fundamentals of how to handle art…It’s the equivalent of walking into a museum here [in New York] and seeing a van Gogh hung upside down.”[10] Overall, these critics claim that Liu and Wang’s intentions and activities have failed to meet the traditional norms and standards of the art world.

These sorts of criticisms are not limited to Liu and Wang. Two businessmen, Adrian Cheng from China and Tony Salamé from Lebanon, both claim to democratize art by showing blue-chip artowrks to shoppers in their high-end malls. Yet critics question their approach to democratization in such commercial settings.[11] Sheikha Al-Mayassa Al-Thani, the sister of the Emir of Qatar, evokes themes like education, heritage, and modernity, but journalists note that her museums are largely empty of locals, and moreover, they point to conservative Qataris who take offense to her acquisitions.[12] The collectors are aware of their criticisms, yet they remain committed to their own depictions of their practices. Facing their critics, they expand their museums and grow their collections—most notably collecting more blue-chip European art. Consequently, they redirect the circulation of such art to new regions.

I argue that these supercollectors do far more than simply move European art out of Europe. Central to their practices is the transformation of the very experience of these cultural objects. Through their museum exhibitions and accompanying catalogs, press releases, interviews, and panel discussions, the supercollectors imbue their European acquisitions with non-European narratives of economic power, national identity, and heritage. Through this process, the supercollectors actually produce new meanings for their art—meanings that are often far removed from the original contexts in which the art itself was produced. There is much more at stake for Europeans than the physical outflow of their cultural objects, then. With the emergence of supercollectors from China and the Middle East, Europeans must come to terms with the new meanings given to the objects that for so long have defined their heritage.

Norms, Meanings, and Historical Change in the Art World

To demonstrate how these collectors actually change the artistic meaning of their collections, it is first necessary to define the meaning of an artwork and outline how it actually comes to be produced. The framework provided by anthropologists Claudia Strauss and Naomi Quinn is useful here because it emphasizes the relation between meaning and the circumstances in which one experiences an artwork. Strauss and Quinn define meaning as “the interpretation evoked in a person by an object or event at a given time…[It] depends on exactly what they are experiencing at the moment and the interpretive framework they bring to the moment as a result of their past experiences.”[13] Accordingly, the moment at which a viewer experiences an artwork depends on where and when it is displayed, which in turn is a function of its circulation in the market. The viewer’s interpretive framework is influenced by the strategies employed to present the artwork. What do the wall labels, promotional materials, and reviews say about it? How is it described by its owner and those in charge of its display? Interpretation is ultimately left to the individual subject, but when an artist, dealer, curator, or collector presents an artwork, he or she can shape how its meaning is conveyed. By production of meaning, then, I refer to an actor’s intentional influence over the moment at which, and interpretive framework through which, he or she experiences a work of art. An actor produces meaning by interpreting the object of interest at a given moment in space and time.

Isabelle Graw, an art historian who studies the art market, demonstrates how the production of meaning in the art market has undergone a recent historical shift. Since the emergence of its first modern form in nineteenth-century France, the art market was structured according to what Cynthia and Harrison White call the “dealer-critic system.” In this system, dealers and critics gained autonomous roles as authorities of taste and interpretation. Dealers speculated on the careers of certain artists and found suitable buyers for their work.[14] Critics theorized and publicized the art they deemed most important. They also instructed the public on how to interpret it—in essence providing their viewers with an interpretive framework.[15] It was in this system that legendary art critics like Clement Greenberg operated. Together, dealers and critics often controlled the presentation of artworks, which audiences they reached, and who could even acquire them. In the process, they controlled how the meaning of such art was produced. Art collectors, on the other hand, tended to play a supporting role; the economic capital they provided allowed dealers to keep developing artists’ careers and critics to keep theorizing their work. For the most part, collectors trusted their dealers and critics to determine which artworks to buy and how to interpret them.

During the 1990s, however, the dealer-critic system was replaced by what Graw calls the “dealer-collector system.” Under this system, critics and dealers gradually lost control over the circulation and interpretation of art. According to Graw, “increasingly influential collectors have long ceased to follow the path set down by critics when shaping their interests and preferences. Instead, they look to their own preferences—and those of other collectors.”[16] Following this reversal, dealers now appeal to the tastes of collectors as they compete with each other for collectors’ business. The supercollectors have become what the art historian and critic Thomas Crow calls “market-moving consumers.” Western supercollectors like François Pinault impose “their own claims to expertise and executive authority over the professional staffs to whose training and experience their predecessors were generally content and even proud to defer.”[17] Under the dealer-collector system, then, supercollectors increasingly control the circulation of art and dictate the presentation of their collections. In the process, they have seized influence over the production of artistic meaning.

Producing Meaning in China and the Gulf

Since the early 2000s, supercollectors from China and the Middle East have joined their European and American counterparts in their control over the meaning-making process. In their independently owned museums and engagement with the art world media, they present radically new physical and discursive contexts for experiencing art. The contexts Liu puts forth are striking. In the international publicity generated by his acquisitions, he rarely describes them in conventional aesthetic and art historical terms. Rather, he employs discourses of national pride and market competition. Across his interviews with Western journalists made after the Modigliani acquisition, he consistently argues that collecting blue-chip art and breaking price records are demonstrations of his country’s emergent economic power. In an interview with the New York Times, Liu explained that “Every museum dreams of having a Modigliani nude. Now, a Chinese museum [the Long Museum] has a globally recognized masterpiece, and my fellow countrymen no longer have to leave the country to see a Western masterpiece. I feel very proud about that.”[18] Liu identifies his personal possession of the “globally recognized” painting as a national accomplishment. He highlights the artwork’s status as a “Western masterpiece” to signal Chinese purchasing power. “The message to the West is clear,” he asserts, “We have bought their buildings, we have bought their companies, and now we are going to buy their art.”[19] Liu constructs a discursive space in which the artwork takes meaning as a measure of power in a global market. While the painting’s aesthetic and art historical meanings remain, they are subsumed within a narrative of economic rivalry between China and the West.

Liu elaborates this narrative using the market for Chinese art and the practice of repatriation. “When we are young,” he explained, “we are indoctrinated to believe that the foreigners stole from us, but maybe it’s out of context. Whatever of ours they stole, we can always snatch it back one day. The laws of the market always rule.”[20] Again, Liu situates the collection of art—both Western and Chinese—in a national rivalry enacted on the market. Here, the flow of cultural objects signals a global hierarchy of power. He references a past in which Chinese cultural objects were forcefully taken from their homeland, and he employs his collection as an example of how this flow has reversed, largely due to the success of businessmen like him. In doing so, he aggressively signals China’s new economic and cultural power. Liu’s collection takes on its meaning in this context. Liu frames his art—both Chinese and Western—as symbols of economic power and national pride. He invites the viewers of his collection to regard it as such and in doing so, contests the interpretations traditionally made of these objects.

The process unfolds similarly in the case of Sheikha Al-Mayassa Al-Thani, sister of Qatar’s current Emir. As chairperson of the Qatar Museums Authority (QMA), the Sheikha directs the foundation of new museums and sponsors exhibitions of living artists from the across the globe. In 2013, QMA sponsored Relics, a Damien Hirst retrospective in Doha. Through this exhibition and its accompanying catalogue, QMA—under the direction of the Sheikha—made Hirst’s opus take on a new significance. One of the essays featured in the text is called “Hirst in Arabia.” It was written by Abdellah Karroum, who is employed by the Sheikha as the current director of Mathaf, the Arab Museum of Modern Art. In this essay, Karroum interprets Hirst’s work in a distinctly Arab context. He writes:

The body of work presented in Hirst’s Doha exhibition reminds us that animals have always existed in the imagery of the Arab peninsula: camels and bees, ants and scorpions…it also draws attention to civilization in these parts as having been built, historically, on the axis of commercial and cultural exchange. [21]

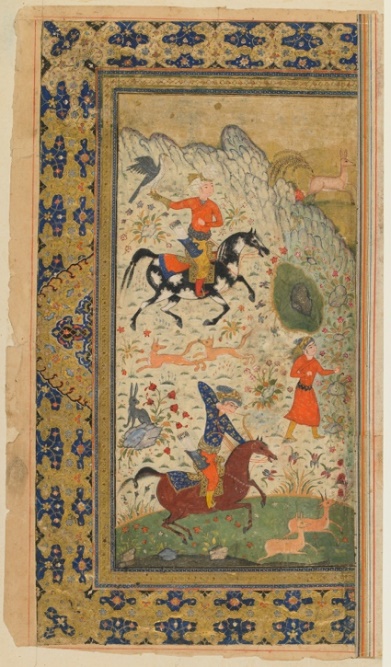

Elsewhere in the essay, he invokes the tales of Arab travelers and Islamic spirituality. In addition, the essay juxtaposes images of Hirst’s work with examples of Middle Eastern art (see figures 2.1 and 2.2 below). These references are far removed from the art’s origin in modern Britain. Through this text, then, Karroum has inscribed Hirst’s work with a new meaning—one rooted in the art’s new (but temporary) location on the Arab Peninsula. As the organizer of both the exhibition and its accompanying text, Sheikha Al-Mayassa was the driving force behind this process. She organized the exhibition, spoke at related events, and hired experts like Karroum to inscribe the art in a narrative about Arab heritage. When viewers encounter Hirst’s work in the exhibition and text, they are primed to engage with this narrative, too.

Figure 2.1: The Immortal, 1997-2005, by Damien Hirst. This was one of the artworks featured in the Relics exhibition.[22]

Figure 2.2: A Royal Hunt, depicted in a Shahnama (Book of Kings) c. 1590-1600, by Firdawsi. This image accompanied Karroum’s essay on Damien Hirst in the Relics exhibition text.[23]

Finding Value in a Collection

The supercollectors spend enormous sums of money to collect and present works of blue-chip art. By acquiring these artworks, the collectors also gain access to the international audiences they attract. What is the value of such an ability? What, for example, does Sheikha Al-Mayassa obtain by paying hundreds of millions of dollars, and by taking on cultural programming as a career, to present the works of artists like Damien Hirst and hire critics to show how they symbolize Arab heritage? I argue that when these supercollectors spend their time and wealth to acquire artworks and reframe their meaning, their practices extend beyond the people and spaces of the art world. The supercollectors mobilize European art in the projects of Chinese and Arab elites.

Sheikha Al-Mayassa employs European art as a tool for Qatari nation-building. Qatar and its neighbors have rapidly transformed into urban and commercial centers. In this transformation, they have been challenged to reconcile their national identity with growing numbers of foreign-born residents.[24] In response, these kingdoms are converting economic capital from oil into cultural capital to strengthen national identities. According to Miriam Cooke, Professor of Arab Cultures at Duke University, the Arab Gulf states are engaging in policies of nation branding “that combine the spectacle of tribal and modern identities and cultures”—a process she denotes with the term “tribal modern.”[25] Central to these policies are investments in culture, education, and tourism that result in the construction of modern public amenities like malls, museums, stadiums, and universities. These amenities are all “branded” with the royal family’s name and images that invoke local heritage. Beyond the promotion of tourism, they reinforce the connection between the royal family and national identity as imagined by the local public.[26]

Qatar’s “tribal modern” project is called the Qatar National Vision 2030. Its guiding document states that “Qatar’s very rapid economic and population growth have created intense strains between the old and new in almost every aspect of life…Qatar’s National Vision responds to this challenge and seeks to connect and balance the old and the new.”[27] This statement reflects the efforts to connect heritage and modernity that characterize the region’s development projects. The document then proceeds to outline a series of abstract priorities like economic diversification, environmental preservation, and social protection—all in the name of the Qatari people and its Al-Thani leaders.

As the sister of the Qatari Emir, Sheikha al-Mayassa Al-Thani has a personal stake in this national vision, and it is this stake that art collecting takes on relevance. When discussing her collecting practices, she asserts that cultural development allows her to enact the 2030 National Vision. In an official interview published by QMA, she explicitly situates her own organization in this project. “What’s exciting [about Qatar’s cultural sector] is that the various entities that are working towards delivering Qatar’s 2030 vision are working together…QM is only one part of the larger picture. We work closely with the Minister of Culture, Arts and Heritage as well as Katara and Qatar Foundation.”[28] She frequently references the mission of the National Vision and uses it to frame her practices. In a TED talk she aptly titled “Globalizing the Local, Localizing the Global,” she explains: “Life necessitates a universal world; however, we believe in the security of having a local identity, and this is what the leaders of this region are trying to do.”[29] After establishing this context, she then describes her museums and shows some work by Arab artists. By consistently framing her practices as a bridge between global and local, Sheikha Al-Mayassa claims that art collecting and patronage can connect her nation with the global community while allowing it to preserve and express its own identity. In this way, she implies that her art collecting can allow her nation to meet its development goals.

The interpretation of art in Sheikha Al-Mayassa’s museums sits in the same discourse as the National Vision, and this explains the seemingly far-fetched comparisons in the “Hirst in Arabia” essay. Links to this discourse are even more evident in the opening chapter of the exhibition text, which Sheikha Al-Mayassa authored herself. To open the book—a book about a British artist—she writes: “Qatari society is at a pivotal moment in its history. It is both fast-changing, yet determined to maintain its core values and traditions. We want to be modern, but in ways that allow us not to forget our heritage.”[30] She echoes of the National Vision document: “Qatar is at a crossroads. The country’s abundant wealth creates previously undreamt of opportunities and formidable challenges.”[31] When she introduces the artwork of a globally recognized artist, she gives it meaning in the terms of Qatar’s national development discourse. When seen in context of the Qatar National Vision 2030, Sheikha Al-Mayassa’s interpretation of her art collection and exhibitions can be seen as a practice of nation-building.

Conclusion

As demonstrated through the cases of Liu Yiqian and Sheikha Al-Mayassa, the supercollectors’ control over both the circulation and presentation of their art has given them the agency to create new meanings for their collections. Often, these meanings are far removed from the circumstances in which the art originated. When presented by Liu Yiqian, art like Modigliani’s Nu Couché signifies the cultural and economic power of China. For Sheikha Al Mayassa, Damien Hirst’s oeuvre communicates her understanding of Arab heritage, not only to other Qataris, but also to the world. While these artworks certainly retain their previous meanings, the ones they take on mark a significant point of inflection in the objects’ histories. Objects that have historically acted as symbols of European heritage and identity are now embodying the historical narratives of new regions.

In this sense, the rise of supercollectors like Liu the Sheikha also marks a significant development for Europeans. Their regional identity has been—and still is—rooted in objects like the ones now owned by the supercollectors. As Isabelle Graw described, the significations of such objects—and in turn what they say about their historical origins—was largely produced by Europeans artists, patrons, critics, and dealers. Now, as more of the most active and influential collectors come from the art world’s “emerging markets,” the meanings assigned to these European cultural objects intersect with historical narratives foreign to European artists and audiences. While this shift can mean a destabilization in artistic meaning, it can also mean the arrival of new possibilities—ones that are certainly worthy of further inquiry.

Spencer Kaplan graduated in 2017 with a BA in International Studies and Economics from the University of Chicago. As an undergraduate, he developed an interest in studying transnational cultural economy. This led him to pursue coursework in various disciplines, including art history, anthropology, sociology, and economics. His undergraduate work culminated in a research project titled “Making Meaning in the Global Art Market: Case Studies of Chinese and Arab Supercollectors.” As part of this project, he analyzed the practices and discourses employed by four well-known art collectors in China and the Arab Gulf. During this project, he wrote the essay he submitted for the CES Undergraduate Prize.

This article is funded by the European Studies Undergraduate Paper Prize, awarded by the Council for European Studies.

References:

Adam, Georgina. “Wang Wei on the Second Long Museum.” Financial Times, May 9, 2014. https://www.ft.com/content/6d4f6990-bf36-11e3-b924-00144feabdc0.

Al Thani, Sheikha Al Mayassa. Globalizing the Local, Localizing the Global, 2010. https://www.ted.com/talks/sheikha_al_mayassa_globalizing_the_local_localizing_the_global.

Al-Thani, Sheikha Al-Mayassa. “Foreward.” In Damien Hirst: Relics, edited by Nicholas Serota, Francesco Bonami, Michael Craig-Martin, Abdellah Karroum, Damien Hirst, and Qatar Museums Authority, First edition. Milano, Italy: Skira, 2013.

“Art Market Trends.” Artprice, 2005. http://imgpublic.artprice.com/pdf/trends2005.pdf.

Chen, Te-Ping, and Olivia Geng. “Chinese Art Collector Stirs Pot With Sip of Tea from $36-Million Cup.” The Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2014. http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/07/21/art-collector-stirs-pot-with-sip-of-tea-from-36-million-cup/.

Cooke, Miriam. Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

Crow, Thomas. “Historical Returns.” Artforum International 46, no. 8 (2008): 284–91.

Fan, Jiayang. “The Emperor’s New Museum.” New Yorker, November 7, 2016.

Firdawsi. A Royal Hunt. Folio from a Shahnama (Book of kings), ca. -1600 1590. Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/edan/object.php?q=fsg_S1986.188.2.

Fromherz, Allen J. Qatar: A Modern History. London: Tauris, 2012.

Graw, Isabelle. High Price: Art Between the Market and Celebrity Culture. Berlin; New York: Sternberg Press, 2009.

Hirst, Damien. The Immortal. Formaldehyde, 2005 1997. http://www.damienhirst.com/the-immortal.

Hossenally, Rooksana. “Qatar’s Royal Patronage of the Arts: Glittering but Empty.” The New York Times, February 29, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/world/middleeast/qatars-royal-patronage-of-the-arts-glittering-but-empty.html.

Karroum, Abdellah. “Hirst in Arabia.” In Damien Hirst: Relics, edited by Nicholas Serota, Francesco Bonami, Michael Craig-Martin, Abdellah Karroum, Damien Hirst, and Qatar Museums Authority, First edition. Milano, Italy: Skira, 2013.

Long Museum – All Exhibitions.” The Long Museum. Accessed March 12, 2017. http://thelongmuseum.org/en/exhibition/all_event/.

“Modigliani’s Nu Couché (Reclining Nude) Leads a Night of Records in New York | Christie’s.” Christie’s, November 10, 2015. http://www.christies.com/features/Modigliani-Nu-couche-Reclining-Nude-leads-a-night-of-records-in-New-York-6782-3.aspx.

“Qatar National Vision 2030.” General Secretariat for Development Planning, July 2008. http://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/qnv/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

Qin, Amy. “Chinese Taxi Driver Turned Billionaire Bought Modigliani Painting.” The New York Times, November 10, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/11/arts/international/liu-yiqian-modigliani-nu-couche.html.

“With Modigliani Purchase, Chinese Billionaire Dreams of Bigger Canvas.” The New York Times, November 17, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/18/arts/international/with-modigliani-purchase-chinese-billionaire-liu-yiqian-dreams-of-bigger-canvas.html.

“Sheikha Al Mayassa: ‘Art Has No Boundaries.’” CNN Money, April 8, 2016. http://www.cnn.com/2016/04/08/arts/sheikha-al-mayassa-art-qatar/index.html.

Sheikha Al-Mayassa, Al-Thani. “Exclusively from Our Chairperson.” Qatar Museums, 2014. http://www.qm.org.qa/en/blog/exclusively-our-chairperson.

Strauss, Claudia, and Naomi Quinn. A Cognitive Theory of Cultural Meaning. Publications of the Society for Psychological Anthropology 9. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

“The Art Market in 2015.” Artprice, 2015. http://imgpublic.artprice.com/pdf/rama2016_en.pdf.

Waldmeir, Patti. “Lunch with the FT: Wang Wei.” Financial Times, January 29, 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/5781c56a-c4f5-11e5-808f-8231cd71622e.

White, Harrison C., and Cynthia A. White. Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World. New York, London, and Sydney: John Wiley and Sons, 1965.

[1] Te-Ping Chen and Olivia Geng, “Chinese Art Collector Stirs Pot With Sip of Tea from $36-Million Cup,” The Wall Street Journal, July 21, 2014, http://blogs.wsj.com/chinarealtime/2014/07/21/art-collector-stirs-pot-with-sip-of-tea-from-36-million-cup/.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Modigliani’s Nu Couché (Reclining Nude) Leads a Night of Records in New York | Christie’s,” Christie’s, November 10, 2015, http://www.christies.com/features/Modigliani-Nu-couche-Reclining-Nude-leads-a-night-of-records-in-New-York-6782-3.aspx.

[4] Amy Qin, “Chinese Taxi Driver Turned Billionaire Bought Modigliani Painting,” The New York Times, November 10, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/11/arts/international/liu-yiqian-modigliani-nu-couche.html.

[5] “Blue-chip” artworks are painted by globally prestigious (usually Western) artists. They are conventionally included in art historical canon. Thus, they are expected to be stable, if not growing, in monetary value. Though these artworks vary in medium, they are most commonly paintings.

[6] “Long Museum – All Exhibitions,” The Long Museum, http://thelongmuseum.org/en/exhibition/all_event/.

[7] In an interview, Wang Wei once said, “I would like the Long museums to become a platform for international exchanges – my models would be MoMA or the Guggenheim.”

(Georgina Adam, “Wang Wei on the Second Long Museum,” Financial Times, May 9, 2014, https://www.ft.com/content/6d4f6990-bf36-11e3-b924-00144feabdc0.)

[8] “Art Market Trends”; “The Art Market in 2015.”

[9] Patti Waldmeir, “Lunch with the FT: Wang Wei,” Financial Times, January 29, 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/5781c56a-c4f5-11e5-808f-8231cd71622e.

[10] Jiayang Fan, “The Emperor’s New Museum,” New Yorker, November 7, 2016, 32–33.

[11] Of Salamé’s opening exhibition, a critic wrote that “the specter of shopping haunts the entire display.” (Kevin McGarry, “At Aishti Foundation, Art Is a Commodity,” Artnet News, November 2, 2015, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/aishti-art-commodity-351914.)

[12] Rooksana Hossenally, “Qatar’s Royal Patronage of the Arts: Glittering but Empty,” The New York Times, February 29, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/01/world/middleeast/qatars-royal-patronage-of-the-arts-glittering-but-empty.html.

[13] Claudia Strauss and Naomi Quinn, A Cognitive Theory of Cultural Meaning, Publications of the Society for Psychological Anthropology 9 (Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 6.

[14] Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World (New York, London, and Sydney: John Wiley and Sons, 1965), 94.

[15] Ibid., 119.

[16] Graw, High Price, 123.

[17] Thomas Crow, “Historical Returns,” Artforum International 46, no. 8 (2008): 8.

[18] Amy Qin, “With Modigliani Purchase, Chinese Billionaire Dreams of Bigger Canvas,” The New York Times, November 17, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/18/arts/international/with-modigliani-purchase-chinese-billionaire-liu-yiqian-dreams-of-bigger-canvas.html.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Fan, “The Emperor’s New Museum,” 32.

[21] Abdellah Karroum, “Hirst in Arabia,” in Damien Hirst: Relics, ed. Nicholas Serota et al., First edition (Milano, Italy: Skira, 2013), 37.

[22] Damien Hirst, The Immortal, Formaldehyde, 2005 1997, http://www.damienhirst.com/the-immortal.

[23] Firdawsi, A Royal Hunt, Folio from a Shahnama (Book of kings), ca. -1600 1590, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., http://www.asia.si.edu/collections/edan/object.php?q=fsg_S1986.188.2. (Appears in Karroum, “Hirst in Arabia,” 37.)

[24] More than 80 percent of Qatar’s population consists of foreign-born workers. (Allen J. Fromherz, Qatar: A Modern History (London: Tauris, 2012), 2.)

[25] Miriam Cooke, Tribal Modern: Branding New Nations in the Arab Gulf (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 10.

[26] Ibid., 67.

[27] “Qatar National Vision 2030” (General Secretariat for Development Planning, July 2008), 4, http://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/qnv/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

[28] Al-Thani Sheikha Al-Mayassa, “Exclusively from Our Chairperson,” Qatar Museums, 2014, http://www.qm.org.qa/en/blog/exclusively-our-chairperson. (Note: QMA was previously referred to as QM.)

[29] Sheikha Al Mayassa Al Thani, Globalizing the Local, Localizing the Global, 2010, https://www.ted.com/talks/sheikha_al_mayassa_globalizing_the_local_localizing_the_global.

[30] Sheikha Al-Mayassa Al-Thani, “Foreward,” in Damien Hirst: Relics, ed. Nicholas Serota et al., First edition (Milano, Italy: Skira, 2013), 11.

[31] “Qatar National Vision 2030,” 1.

Published on October 2, 2018.