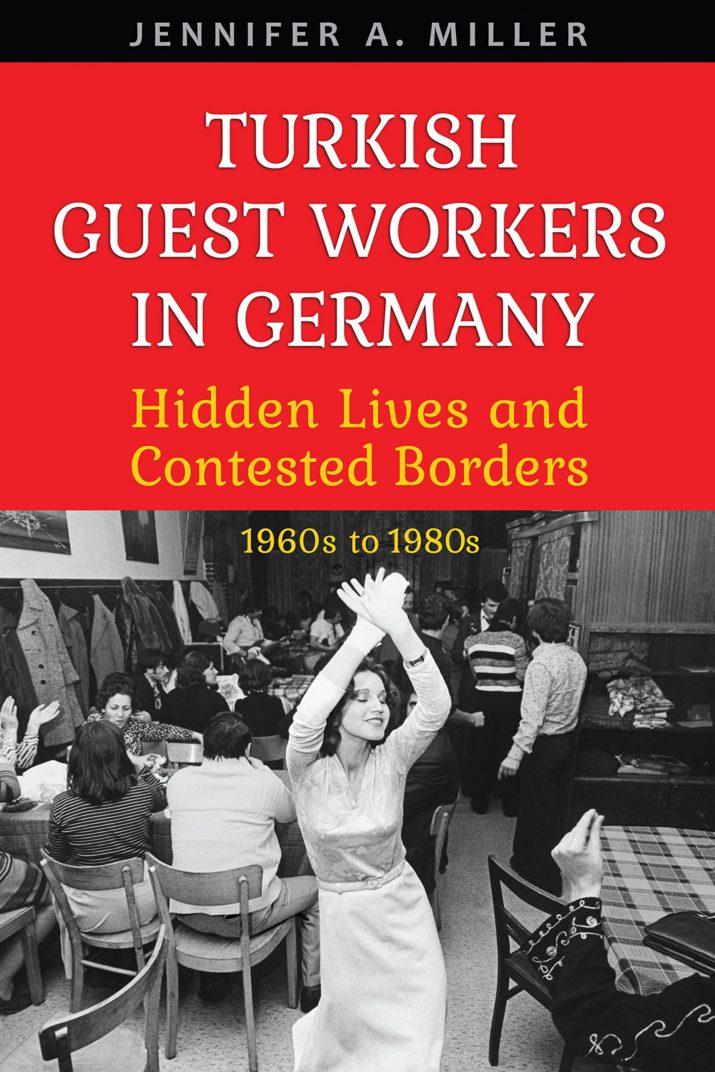

Turkish Guest Workers in Germany: Hidden Lives and Contested Borders 1960s to 1980s by Jennifer Miller

Historians often rely on a preponderance of evidence to stake their claims. In so doing, however, these scholars frequently get lost in the numbers and the trends, forgetting the individual. Jennifer Miller’s much-needed 2018 Turkish Guest Workers in Germany: Hidden Lives and Contested Borders, 1960s to 1980s shows readers that groups of people—even when they number in the millions—are made up of individuals, each of whom has unique experiences.

Historians often rely on a preponderance of evidence to stake their claims. In so doing, however, these scholars frequently get lost in the numbers and the trends, forgetting the individual. Jennifer Miller’s much-needed 2018 Turkish Guest Workers in Germany: Hidden Lives and Contested Borders, 1960s to 1980s shows readers that groups of people—even when they number in the millions—are made up of individuals, each of whom has unique experiences.

That emphasis is the crux of Miller’s—an Associate Professor at Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville—argument. Taking the reader through the process of application and arrival as well as exploring some successes and failures of integration, Miller argues that even with hundreds of thousands of people undergoing similar processes, their experiences were unique. Weaving together interviews and archival material from both Germany and Turkey, Miller shows how these individuals were not passive participants but active protagonists in their own lives (6), often enjoying life even as their situations were far from ideal. Even as the West German government’s programs attempted to dehumanize recruited workers, treating non-German residents as labor instead of people, Turkish workers often found joy where they could and fought to improve their situations (146, 168).

Miller’s approach to her subject deepens the importance of her argument by allowing her to uncover hidden lives while making a necessary contribution to European Cold War as well as West German social and guest worker historiographies. In doing so, Turkish Guest Workers in Germany highlights how interconnected these different histories actually were. First and foremost, select oral interviews allow Miller to explore how both women and men experienced labor migration from Turkey to West Germany between the 1960s and 1980s against an East-West conflict. Adding to that, however, those first-hand accounts combined with archival material and scholarly literature further enable Miller to build on multiple ongoing scholarly debates, including discussions over how labor migration affected West German social development particularly in regards to family structures. Here, building on Monika Mattes 2005 argument, Miller shows how, by recruiting hundreds of thousands of workers from countries like Turkey—one-third of whom were women—West German government and businesses were able to exclude German women from the workforce and instead promote a male breadwinner, nuclear family (7, 149).

Miller’s deft use of her sources similarly allows her to engage with international political history as well as labor history across an introduction, five chapters in two sections, and a conclusion. The book’s introduction serves as a chapter in itself, not only defining the book’s goals and intentions but also clearly establishing the historical, Cold War context and idea of “Turks.” That framing allows the book’s two parts to dive into the experience of migration and a few specific components of settlement. The first part of the book, divided into three chapters, emphasizes the process of labor migration. The first chapter, “The Invitation,” takes the reader through the establishment of the West German-Turkish bilateral labor agreements, the creation of recruitment offices in Turkey, and the often-dehumanizing application process the West German government required Turkish workers to undergo. This, as Miller demonstrates, was not a process that focused on employment qualifications so much as meeting West German expectations of health and literacy. The second chapter, “In Transit,” follows the chosen workers into trains and along the route from Istanbul to Munich before dispersal across the country. Here, as Miller tells readers, workers experienced the first glimpse of the treatment they could expect in the Federal Republic (77). “Finding Homes” underlines that point, highlighting the missed opportunities for integration and collaboration as first employers provided workers inadequate housing and then landlords discriminated against the now-called “guest workers.” Miller shows how, even as the West German economy relied on recruited labor, the state and employers often intentionally made the experience unpalatable in order to encourage eventual re-migration. Nonetheless, even as the West German government and employers tried to control workers’ private lives, individuals still expressed themselves and found space for self-expression (96, 100).

In the second part of Turkish Guest Workers in Germany, Miller illustrates the continuation of that rejection and other opportunities the West German government and majority communities missed to promote worker solidarity as well as guest workers’ choice and activism. Here Miller demonstrates how Turkish workers were often kept on the margins, frequently excluded from West German society and politics long after arrival. In order to highlight that social distance, Miller’s fourth chapter, “Contested Borders,” takes readers out of West Berlin and over the contested border with the East to give readers an outsider’s—here the Stasi’s—perspective. This chapter at first glance feels out of place but the brief feeling of dissonance highlights the individuality of experience as a few thousand men (out of hundreds of thousands) looked for love and adventure in East Germany. Miller further uses those men’s experiences to show how the West German rejection of Turkish laborers enabled these workers to cross the border with greater ease than the German citizens on either side. The very exclusion and capitalist abuse these workers faced in the West made them more acceptable in the East. The final chapter, “Imperfect Solidarities,” follows that theme of West German rejection back into the West, looking at labor activism in the 1960s and 1970s. Here, Miller demonstrates how even if the West German labor unions may have initially demanded foreign workers receive comparable wages with German, over the two decades wage disparity rose exponentially (142-145). Turkish workers, to the Brandt government’s disconcertion, responded by agitating for their rights as laborers. Taken together, these two chapters show just how much Turkish workers’ positions and very humanity in West Germany were contested. Miller’s book is not, however, a tragedy, but an examination of different experiences and an important reminder that the people involved in labor migration were individual people with their own stories.

This book is a must read for scholars of twentieth century German history and an excellent addition for undergraduate classrooms examining modern or twentieth century European or world history. Miller’s historicization in the introduction combined with her richly detailed narrative in subsequent chapters provide a study that is simultaneously in-depth but also readily comprehensible. The smooth writing, short sections, and use of images open the door for multiple possible classroom discussions. This reviewer’s main critique is directed not at the author but the publisher: the book’s print formatting is a problem. The tight text and almost-non-existent margins make the physical experience of reading the book unpleasant. The physical experience aside, this reviewer highly recommends this book even to casual readers. With its body coming in at just under 200 pages, this book is a rapid and informative read.

Reviewed by Brittany Lehman, College of Charleston,

Turkish Guest Workers in Germany: Hidden Lives and Contested Borders 1960s to 1980s

By Jennifer Miller

Publisher: University of Toronto Press

Paperback / 271 pages /2018

ISBN: 978-1-4875-2192-9

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on September 5, 2018.