Translated from the Danish by Susanna Nied.

What We Don’t Talk About

There are a few, very few, things worth talking about—and we don’t talk about them. We can’t talk about them. For instance life, death, and love. We give them big, expensive names, something like a dress so good that we’re not comfortable wearing it. We’re shy. We’re afraid. So we don’t mention it. That kind of word is left hanging in the closet, while we use all the nice, ordinary, and undeniably practical words in our daily dealings with each other.

We’re afraid. But we manage. We’re afraid to be alone and afraid to be with others; afraid of what’s finished, at a standstill, too orderly; and afraid of what’s unfinished, messy, and disorderly—and we’re afraid of sex, afraid of death. But we manage. Or do we? Could it be that the reason we’re still having wars is that we’re afraid to tell each other that we’re afraid of each other, and of everything else? To me it’s as if we keep going out in the rain—and keep refusing to invent raincoats and galoshes.

What We Don’t See

We don’t talk about the things we don’t know anything about, the things we can’t do anything about, the things we can’t see. But those are the things that fascinate us. If a person seems attractive, ultimately it’s not because of this or that external feature; it’s because of the internal interplay among those features. And that interplay is invisible. We’d like to be able to guess one another’s thoughts, put ourselves in one another’s place—you just can’t tell what’s going on in people’s minds, we say. All we know is that there’s something else, something more than what we see.

This recalls a Baroque anecdote (related by Saint- Simon): One winter a set of wax masks had been made to look like all the people of the court. At a ball the wax masks were worn under other, ordinary ball masks, and when the ordinary masks were taken off, everyone was fooled and thought they were standing with the real person, but they were really standing with a wax mask of one of the other people there. Underneath, there was someone entirely different. Everyone was greatly amused by this joke.

What We Don’t Do

Underneath, there’s someone entirely different. That’s certainly worth talking about: how to get this other, fearful, helpless person out, so he’s no longer so afraid of being helpless that he has to wage wars to battle his own fear. One of Gunnar Ekelöf ’s notations:

“I have, in imagination, lived through all the shamelessness and corruptibility of which the first half of the 20th century consists. I have also, at a much earlier age, seen people pale, in shock, along Unter den Linden, and during that same year I saw battlefields with not a house left standing, not a tree. That was in 1920. And then the war in Spain. And then World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and racism on all fronts, lust for power on all fronts. I want to serve … But I will never forget what I have seen, and I think about it constantly. How shall human beings be good human beings. At times I think that human beings are evil animals; at times I think I glimpse a solution, perhaps when I’m in a woman’s arms.

I see no other solution for humanity than an underground one … the secret meal, underground opposition to all forms of oppression…

Someone has said: We must change ourselves, if the world is to be changed. That is not a Christian thought; it’s heathen. That’s the way I see it.”

That’s pretty much the way I see it, too. The individual must change himself. Must show that underneath, there’s someone entirely different.

What We Do Anyway

“I have, in my imagination, lived…” says Ekelöf. In imagination. That is, in words. He said that he was afraid, and he told us that at last he was no longer afraid of being afraid, because he had figured out that he wasn’t anyone special and had accepted it—“In reality, you are no one”— and found a kind of comfort in that. The important thing is that he had the courage to keep telling it to others, to say it again and again: I’m afraid. I’m no one. Isn’t that the way it is for you too? … How else can we put aside the lust for power in all of us?

What We See Anyway

Of course we can see perfectly well that that’s the way it is. We just don’t like to face it. And if we finally do face it, we close our eyes tightly afterward, so it can’t slip out and disturb us any more. We think we’ve put a truth in its place so firmly that it neither will nor can move any more. But there is no truth. There’s only a movement toward … no, not toward a truth, maybe toward a better humanness, a better life with each other. Many people tell themselves that poetry is certainly one thing that has to tell the truth (or at least to tell some truths). But poetry is not truth— it’s not even the dream of truth—poetry is passion—it’s a game, maybe a tragic game, the game we play with a world that plays its own game with us.

What We Talk About Anyway

An old Chinese anecdote about pure passion:

The master said to his followers: “I need someone to carry a message to Hsi-t’ang. Who will take it to him?”

Wu-feng said, “I will.”

“How will you get the message to him?”

“When I see Hsi-t’ang, I’ll tell it to him.”

“What will you say?”

“When I come back, I’ll tell you.”

Through this writing, I’ve been trying to get to the heart of my relationship with my readers.

I want them to talk about what they don’t talk about. What we talk to ourselves about anyway, deep inside.

I want them to see what they don’t see. What we see all the time anyway, but are afraid to put into words.

I want them to do what they don’t do. What we want to do anyway, if we ever could become helpless enough to

do it.

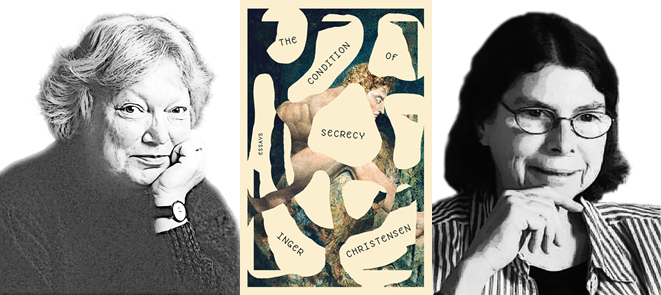

Inger Christensen (1935– 2009), whose work is a cornerstone of modern Scandinavian poetry, was the recipient of many international awards, among them the Nordic Authors’ Prize, bestowed by the Swedish Academy and known as the “Little Nobel.” Her books include the masterpiece it; alphabet; Butterfly Valley; and Light, Grass, and Letter in April.

Susanna Nied is an American writer and translator. Her translations have appeared in publications such as APR, Poetry, Granta, Tin House, and Two Lines, and in several anthologies. For her work with Inger Christensen’s poetry, she has received the Landon Translation Prize of the Academy of American Poets, the American-Scandinavian Association/PEN Translation Prize, and the John Frederick Nims Memorial Prize of Poetry Magazine. She was selected as a finalist for the PEN Award for Poetry in Translation.

This excerpt from The Condition of Secrecy: Essays is published by permission of New Directions Publishing. Copyright © by Inger Christensen and Gyldendal Copenhagen. Translation Copyright © 2018 by Susanna Nied.

Published on September 5, 2018.