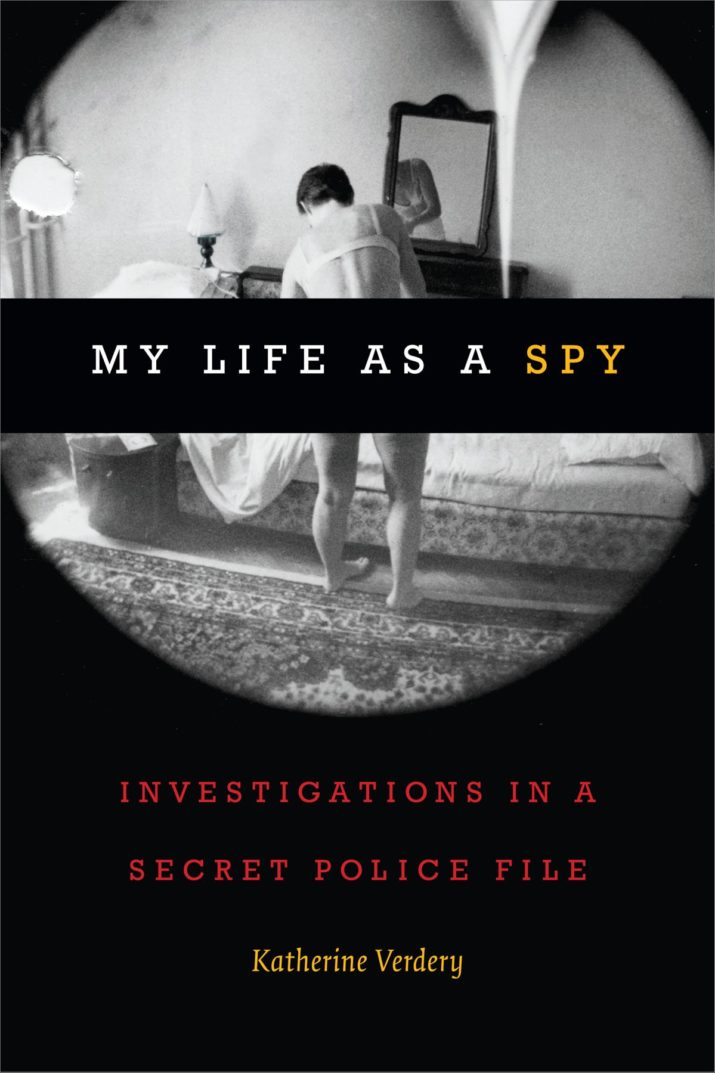

In the prologue of her book, My Life as a Spy: Investigations in a Secret Police File, Katherine Verdery probes herself and the reader, “To be honest, I don’t actually know what this book is” (28). Verdery’s immediate frankness sets an explorative and provocative tone to her book which is part memoir, part ethnography, and part extrapolation of Romania’s secret police during the communist era, the Securitate.

In the prologue of her book, My Life as a Spy: Investigations in a Secret Police File, Katherine Verdery probes herself and the reader, “To be honest, I don’t actually know what this book is” (28). Verdery’s immediate frankness sets an explorative and provocative tone to her book which is part memoir, part ethnography, and part extrapolation of Romania’s secret police during the communist era, the Securitate.

Verdery, one of the first anthropologists to explore beyond the Iron Curtain during the Cold War, has spent over four decades conducting fieldwork in Romania. My Life as a Spy constitutes an impressive work that not only brings together years of research and analysis but also retrospectively studies and critiques anthropological methodologies. This reflective evaluation emerges from Verdery’s weaving together of several voices including her notes from fieldwork of years past, the reports of secret police and informers, and her current thoughts and understandings.

With these narrations, which span time and space, Verdery breaks the book down into two halves: the first considers her experience researching under surveillance (when she was mostly unaware that she was being monitored), while the second delves into the mechanisms of surveillance. The first two chapters in Part I draw heavily from her fieldnotes from the 1970s and 1980s (she conducted research in Romania almost continuously from 1973 to 1989) and the archival research she undertook on her secret police file at the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives (CNSAS) in the 2010s. Having her original fieldnotes juxtaposed against the reports of her invisible observers, the officers and informers spying on her, Verdery brings to the fore the paranoia and power of Cold War surveillance while also evaluating anthropological methods.

After accidentally riding her motorbike into a military base in the early days of her fieldwork, the Securitate opened a secret file on her. By 1989, as her research progressed and her network of contacts expanded, the secret police had postulated four different spying identities for her: an agent conducting military espionage, gathering sociopolitical information, riling up Hungarian opposition, and/or conspiring with dissidents. All these identities, which were proliferated by different officers located in various villages and cities, reveal a totalizing concern for Romanians at the time: the denigration of Romania’s image in the world. Under peak Cold War mentality, a western academic and possible spy could tarnish the global image of both Romania and the socialist system in general through potential pervasive publications.

The most salient take away from Part I is the cogitative examination of anthropological field methods. As the reader comes across excerpts of Verdery’s old fieldnotes and then an officer’s subsequent take on a particular situation or context, one begins to wonder who is surveilling whom? While Verdery draws many parallels between spies and anthropologists, she is also quick to note the differences between the two. Anthropologists and spies both create codes for their writing, pseudonyms for their interlocutors, mention the place and context of discussions, and make note of their informers’ attitudes. Yet, unlike anthropologists, spies do not make the effort to feel and experience “with their whole beings while seeking to stand back and analyze those feelings and experiences” (182). The ethnographer interrogates their own feelings, which is a vital data point for anthropological studies.

Verdery highlights the vulnerability of her emotions and experiences by sharing fieldnotes where she describes feelings of hopelessness and despair during particular stressful moments in her ethnographic endeavors. She also documents her emotions as she carefully read her secret file in 2010. This introspective dive into Verdery’s psyche makes her research experience and writing relatable. It also highlights issues concerning wellness and mental health in the field, a topic that is rarely addressed in anthropological literature or in the classroom.

Verdery’s reflections on reading her file segue into Part II of her book, where she unpacks the ways in which the secret police operated. Through her close analysis of the notes in her file, in conjunction with conversations with some of the informers and officers that reported on her, Verdery works to paint a variegated, rather than monolithic and totalitarian, identity of the Securitate. By no means is she excusing or whitewashing their behavior, but she is careful to note that she intends to “understand them [the Securitate] as part of a social system” (270) a task that can only be done now that the Cold War is over.

To examine this social system, Verdery unravels ideas of victimization, the definition of betrayal, and the processes of blame making. Her analysis of these topics reveals that the Securitate were able to operate affectively and to recruit many informers due to the strong sociability of Romanians. Civilians enlisted to report on their friends, colleagues, and family members were compelled to do so as the secret police would threaten to destroy their valued social relationships if they did not comply. Subsequently, informers would keep mum about their surveillance roles so as not to outwardly betray the trust and confidence of their social networks. In remarking on the value of social trust and stability, Verdery notes that in order to understand the system in which the secret police successfully functioned, she had to drop her “very American tendency to think largely in terms of autonomous individuals” and the “too shallow [American]…understanding of a friendship” (227, 228). Loyalties and friendships take years, if not lifetimes, to build among Romanians. Initially, it is this disconnect between American and Romanian understandings of friendship that lends Verdery a great deal of stress as she reads through her secret police files, which contain reports from over seventy informers, many of whom she considered close friends. She agonizes, at first, over the breach of trust her friends committed against her, but then realizes the inescapable pressure and heartache informing brought to her friends. She ends one of her chapters on an uplifting, conciliatory note, stating that despite the extreme societal pressures and threats many of her friends felt under the surveillance of the Romanian secret police, many of her friendships endured and became some of the most meaningful of her life, stating, “If anything proves that the Securitate failed in their goal of insulating Romanians from foreigners, it is that” (276).

The personal, raw tone of Verdery’s writing makes this book not only extremely accessible but also relatable. Halfway through My Life as a Spy, Verdery poses again the question she states in the prologue, exclaiming “What exactly WILL I accomplish with this book?…What’s the point of it anyway? Why should I think anyone will be interested in it?”(188). This book constitutes an excellent, detailed foray into the workings of a surveillance state in the Soviet bloc. But ultimately, this book’s strength emerges from its transparency concerning anthropological methodologies, an openness that comprises a foundational read for not only anthropology students but also for any social scientist working in post-socialist states. Through her frankness, Verdery reveals the multitude of emotions, analyses, and feelings it takes to conduct fieldwork. Anthropological research, in essence, relies on relationships between the ethnographer and their interlocutors. Verdery’s writing shows the power of these relationships and the difficulty and joy in maintaining them.

Reviewed by Sabrina Papazian, Stanford University

My Life as a Spy: Investigations in a Secret Police File

By Katherine Verdery

Publisher: Duke University Press

Hardcover / 344 pages / 2018

ISBN: 978-0-8223-7066-6

To read more book reviews click here.

Published on September 5, 2018.