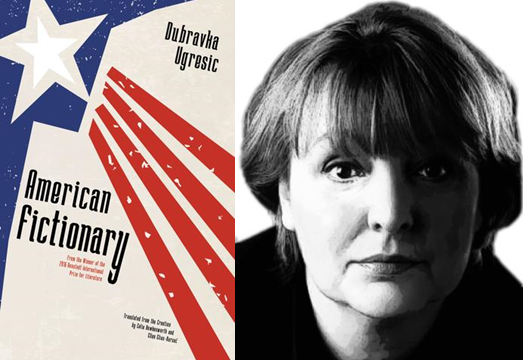

Translated from the Croatian by Celia Hawkesworth and Ellen Elias-Bursac.

Missing

My mother collects other people’s deaths, rattling them mournfully like coins in a piggy bank.

“Did you know Petrović died?” asks Mother over the phone.

“Really?” I say, although I have no idea who this Petrović is.

“Yes, imagine, a heart attack,” says Mother, stressing the words.

“Oh,” I say.

“Poor man,” sighs Mother, ending her little verbal funeral rite. And she files Petrović away in her mental piggy-bank.

Mother tells me these sorts of things. Talking about them allows her to prolong anonymous Petrović’s life for another moment, light him an invisible candle; by counting out other people’s deaths like pocket change she holds her own fears at bay.

But I’m not interested in deaths. They are so final. I’m interested in disappearances.

One year my Zagreb friend Knaflec disappeared as well. People said he’d gone to America. When I first went to America, someone gave me his phone number. I called the number, somewhere in Texas. He answered, but the person I was speaking to was no longer my friend Knaflec. Now I don’t think of calling him—he too has disappeared.

And then one year there was a journalist who took up my favorite theme of disappearance and wrote an article about it. It turned out that 2,847 people had disappeared in Yugoslavia that year. I even remember the exact figure. That year, 2,847 Yugoslavs could not be found among the living or the dead.

I find New York the most confusing. As I walk through the city’s streets I often think I must be in the middle of a nightmare. I see a man with a plastic bag. There’s a long stick of American celery poking from it. And I can clearly see: he’s my friend Nenad. “Hey, Nenad,” I call. “Hey, what are you doing here?” He looks at me but doesn’t recognize me. Goodness, I whisper, confused. He shrugs his shoulders and walks on with the long stick of celery in his bag.

A taxi passes. In it is my friend Berti. “Hey, Berti!” The taxi stops at a crossing, the light’s red. “Hey, Berti!” Berti looks at me through the window, he smiles but he doesn’t recognize me. What’s this, I think, if he were here, if that were Berti, he’d surely say hello, I think. But I’m not certain.

At the park I watch a cleaner clearing away dry leaves. He blows them away with an enormous leaf blower, making rustling, golden-yellow heaps. A magician. For a moment I clearly see the profile of my friend Pavle. “Hey, Pavle, how come you’re here?” I shout. “Hey!” I go up to him and tap him on the shoulder. He turns around and says, in English, with no foreign accent: “Stop that, ma’am, or I’ll call the police.”

So I give up. The newspaper seller on the corner is my Zagreb friend, Vilma. I buy the papers from her every day on the corner of Eighth Street and University Place. I gaze at her for a long time, put the money into her hand knowingly and take my New York Times. I don’t say a word, I’m no longer insisting, I pretend I don’t know she’s Vilma. “Thank you, have a nice day.”

Here in Middletown the situation is altogether different. It’s a small town, I don’t know a soul, I’m a stranger, they’re at home, locals. But still, to be on the safe side, I memorize every face. The salesperson at Bob’s, the cashier at Waldbaum’s, the waiter at the Opera House, the cop by the Clock Tower. I let my eyes range over the names in the local telephone directory. Brigith, Gloria; Kilby, Peter; Hills, Karen . . . I don’t know anyone. I feel safe and serene. Everything is as it should be. I’m a stranger, they are locals, at home.

At about noon each day the mailman comes and brings the mail. I open the Zagreb newspapers of November 29, 1991. I read an article about missing persons. Thirty thousand missing persons have been registered in Croatia, writes the author. People are looking for their vanished brothers, husbands, wives, children, parents. Not only have several villages and towns been razed to the ground, but these 30,000 people are gone as well. They can no longer be found among the living or the dead.

Terrible, I think. It’s just as well that I’m here where it’s safe. I’m a stranger here, they’re all at home, everything is as it should be. Someone called Peter lives near me, someone called Gloria, someone called Karen. I’m protected, nothing can happen to me.

Suddenly I hear the doorbell, I go to the door, open it—and people I have never seen before surge into my apartment. They pour in uncontrollably like a flood, women, children, old men, the wounded, soldiers. “I’m Željko,” a young man introduces himself, “it’s two months since I went missing somewhere near Pirot, my sister Ljubica Oreški is looking for me.” “I’m a mother,” mumbles a woman, “I disappeared in September, somewhere near Drniš; my son, Rade Brakus, is looking for me.”

And I understand, here they are, all 30,000. “Come in,” I say, “find somewhere to sit, make yourselves at home, we’ll manage somehow.” They arrange themselves quietly. There are so many, I think, and they all fit into my small apartment, as if they were transparent, I think, as if they were playing cards, one laid down over the other. That’s because they’ve disappeared, I think, that’s why they’re so collapsible.

And as I cook a meal to feed them all, I think about how the globe is like an egg-timer, like communicating vessels, there’s a copy of everything, as in a library. There’s a Berlin here in my neighborhood, ten minutes’ drive away, West and East, nothing has been left out. There’s a copy of everything somewhere, especially here, there’s a Paris in Texas, and a Moscow and a Madrid and a Copenhagen and a Venice and a London and a Hamburg, and New York is merely another name for New Amsterdam . . . The missing don’t disappear, then, they simply spring up elsewhere, for instance in my apartment. It’s all right, I think, everything’s all right, there’s no need to worry, I’ll look after your brother, Ljubica Oreški.

The telephone rings, it’s my mother calling from Zagreb.

“Did you know . . .” she begins slowly and I already anticipate the familiar, soft rattle in the receiver.

“I know, Mother, no need to tell me. They’re here, we all are,” I say, and I hear a rich jangle like a slot machine suddenly spitting out a whole pile of coins.

Dubravka Ugresic is the author of seven works of fiction, and six essay collections, including the NBCC award finalist, Karaoke Culture. Exiled from Croatia, she currently lives in the Netherlands.

Celia Hawkesworth is the translator of numerous works of Serbian, Croatian, and Bosnian literature, including Dubravka Ugresic’s The Culture of Lies for which she won the Heldt Prize for Translation in 1999.

Ellen Elias-Bursac is a translator of more than a dozen works, including several by David Albahari, Dubravka Ugresic, Daša Drndić, and Karim Zaimović. She is co-author of a textbook for the study of Bosnian, Coratian, and Serbian with Ronelle Alexander, and author of Translating Evidence and Interpreting Testimony at a War Crimes Tribunal: Working in a Tug-of-War, which was awarded the Mary Zirin Prize in 2015.

This excerpt from American Fictionary is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © TK Translation copyright © TK

Published on September 5, 2018.