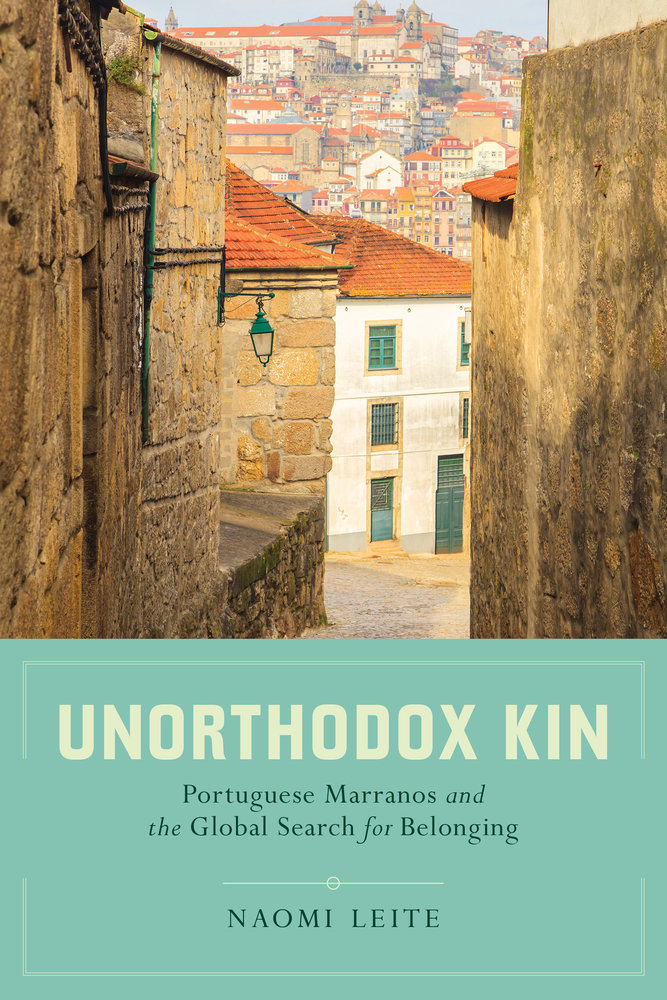

It should come as no surprise that in a world where one can map their genetic ancestry and receive a detailed display of their family tree that heritage tourism is one of the fastest growing sub-categories of travel (Park 2013). As Naomi Leite compellingly argues in her recent book Unorthodox Kin: Portuguese Marranos and the Global Search for Belonging, these trends speak to deeper questions that have gripped the discipline of anthropology since its founding—namely, kinship and belonging. The result of eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in the Portuguese cities of Porto and Lisbon, Leite offers a deep examination of “urban Marranos,” a group of Portuguese who claim to be the descendants of Jews forced to convert during the Inquisition. Their attempt to forge a community in Portugal and to assert themselves as Jewish reveals the complexities of what it means to belong and the continued importance of kinship in a globalized world of shifting identities and allegiances. As Leite shows, urban Marranos undertake a process of “becoming” Marranos, which entails discovering or realizing their Jewishness and then adopting a set of practices to make and reinforce their identity. It is here that Leite turns her attention to the ways globalization facilitates the urban Marrano identity, allowing Marranos to uncover their shrouded history by connecting to Jewish scholars in other parts of the world, and through heritage tourism in which Marranos and Jewish communities from across the diaspora meet in face-to-face encounters in Portugal via walking tours and shared meals. Given the immediate possibilities for the building of connections between communities separated across time and space, particularly in the context of Europe where social upheavals over the last 500 years resulted in forced conversions, repressed political movements, and far-flung routes of migration and colonization around the globe, Leite’s ethnography provides an important entry point for thinking through this phenomenon.

It should come as no surprise that in a world where one can map their genetic ancestry and receive a detailed display of their family tree that heritage tourism is one of the fastest growing sub-categories of travel (Park 2013). As Naomi Leite compellingly argues in her recent book Unorthodox Kin: Portuguese Marranos and the Global Search for Belonging, these trends speak to deeper questions that have gripped the discipline of anthropology since its founding—namely, kinship and belonging. The result of eighteen months of ethnographic fieldwork in the Portuguese cities of Porto and Lisbon, Leite offers a deep examination of “urban Marranos,” a group of Portuguese who claim to be the descendants of Jews forced to convert during the Inquisition. Their attempt to forge a community in Portugal and to assert themselves as Jewish reveals the complexities of what it means to belong and the continued importance of kinship in a globalized world of shifting identities and allegiances. As Leite shows, urban Marranos undertake a process of “becoming” Marranos, which entails discovering or realizing their Jewishness and then adopting a set of practices to make and reinforce their identity. It is here that Leite turns her attention to the ways globalization facilitates the urban Marrano identity, allowing Marranos to uncover their shrouded history by connecting to Jewish scholars in other parts of the world, and through heritage tourism in which Marranos and Jewish communities from across the diaspora meet in face-to-face encounters in Portugal via walking tours and shared meals. Given the immediate possibilities for the building of connections between communities separated across time and space, particularly in the context of Europe where social upheavals over the last 500 years resulted in forced conversions, repressed political movements, and far-flung routes of migration and colonization around the globe, Leite’s ethnography provides an important entry point for thinking through this phenomenon.

Leite is incredibly clear in mapping the stakes of the book and the thrust of her argument. Unorthodox Kin is a “book about the desire for belonging” that explores “the ways the cultural logics of kinship inform imaginings of self in relation to others” (5). The urban Marranos’ uncovering of their identity and assertion of it to the wider Portuguese Jewish community was met with rejection and dismissal, and yet their assertion of that same identity to the wider Jewish diaspora via the internet and tourism encounters produces a sense of belonging that upends our intuitive sense of the global and the local, particularly as it relates to kinship. As Leite informs us, the contemporary Jewish communities in Portugal are relatively recent, the result of immigration from other parts of Europe during the twentieth century. The urban Marranos in Leite’s account claim a much older lineage, from the time of the Inquisition, but do so without much knowledge of the Jewish religion, Jewish customs, or Jewish history. Leite’s ethnography thus “proceeds through a series of turning points in the Portuguese Marrano movement” tracing their recent history through the deployment of a narrative that is as much analytically rich as it is equally committed to the notion that identity as incomplete, that the ethnography of this group is itself “unfinished” (Biehl and Locke 2017). The chapters that follow the introduction stay true to form, beginning with a history of the Marrano community and Judaism in Portugal, followed by an account of what it means to become Marrano both as a matter of individual discovery (chapter 2) and social interaction (chapter 3), and finally the last two chapters of book delve into the role of the tourist encounter (chapter 4) and global Jewish community (chapter 5) in the formation of Marrano identity.

Throughout the ethnography, Leite consistently utilizes contradiction to analyze the curious situations of Marranos as both a movement and an identity. In chapter 1 she traces the history of the Marranos, taking us from the Inquisition and the forced conversions, to the discovery of rural Marrano communities by journalists and travel writers in the early 1900s. It is this history that serves as the starting place for many Marranos, whose assertion of Jewish identity is at once an attempt to affirmatively link themselves to this past as much as it is about linking that past to their present. This is what takes us into chapter 2 of the book, in which Leite describes the various ways by which her interlocutors came to identify, or “adopt,” the Marrano identity. Here she examines three ways in which her interlocutors came to see themselves as Marrano—through a relative, through “fascination” with Jewish culture, and most curiously, via the assertion of a Jewish soul or gene. Building on Zygmunt Bauman’s work on the subjective liquidity that accompanies our particular moment of modernity Leite shows how her interlocutors assert a “rhetoric of essence” in which the process of becoming Marrano, a process laden with particular choices, is understood as a revealing of one’s essence or true form.

Moving to chapter chapter 3 Leite extends this argument further, documenting how the individual discovery of one’s identity as Marrano soon confronted the more restricted category of Jewish. Marranos learned that while they could assert an ancestral past, their claim of Jewishness as a religious-legal category would be scrutinized and even rejected by Portugal’s established Jewish community. These experiences allow Leite to make her case that kinship is both a site of intimacy and belonging as much as it is a space of exclusion. The experience of not finding belonging among Jews in Portugal takes us into the final two chapters of the book, where Leite describes the role of the internet and global travel in fostering connections between Marranos and Jewish communities around the globe. Here we receive another twist on the classic model of tourism in which guests experience the lives of their exotic hosts (Smith 1989). As Leite shows, Jewish tourism to the Marrano communities is not about heightened difference, but rather about fostering connections that produce a sense of belonging that extends across time and space. This is, of course, the general promise of heritage tourism as it relates to the Marranos, in that it allows Jews from around the world whose ancestors may have been the victims of historical tragedy to reclaim the past in the present, and in doing so, establish new bonds under older, and indeed in the case of Marranos, sacred terms.

Overall Leite’s ethnography is a compelling read and an excellent piece for thinking through the increasing overlap between tourism and kinship, both analytically and in practice. With its hefty ethnographic attention to detail, however, certain parts of Leite’s analysis could have been fleshed out further. For instance, comparing Leite’s findings with the theoretical insights of the Comaroffs’ Ethnicity Inc. (2009), one might ask what this sense of belonging forged through practices of identity making tells us about contemporary politics in Portugal, particularly in light of the country’s recent neoliberal reforms and its turn towards tourism as an economic generator. Leite offers an interesting historical account of the emergence of the urban Marrano community, but the political elements of this phenomenon are pushed to the side at the expense of attending to the ways kinship and tourism, particularly on such global scales, are power-laden and inflected by political-economic forces as much as personal desires for belonging. That said, Unorthodox Kin proved to be an incredibly thoughtful piece of scholarship innovatively charting new pathways for tourism scholarship and raising important questions about the meaning of belonging in our globalized world.

Reviewed by Brandon Hunter, Princeton University

Unorthodox Kin: Portuguese Marranos and the Global Search for Belonging

By: Naomi Leite

Publisher: University of California Press

Hardcover / 344 pages / 2017

ISBN: 9780520285057

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on June 5, 2018.

References:

Biehl, João, and Peter Locke, eds. 2017. Unfinished: the anthropology of becoming. Duke University Press.

Comaroff, John L., and Jean Comaroff. 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Smith, Valene L. 1989. Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.