Translated from the Spanish by Will Vanderhyden

I don’t remember my mother.

My mother—known as “Fair Sarah”—died during the great influenza epidemic, when I was less than a year old. I got sick too. And against all prognoses, condemned by the doctors, I survived, and no one dared call it miracle: there had been so many victims that my modest resistance was more an unrepeatable statistical anomaly than a singular divine gesture.

My name was Isaac, which means laughter in ancient Hebrew; but I wouldn’t say I laughed a lot as a child; there weren’t many things to laugh about in my childhood.

And I can’t remember what my father was like before my mother’s death either. But I do remember how he was after she died. And how my mother seemed to have replaced his shadow, sewing herself to his heels and accompanying my father, Rabbi Solomon Goldman, at all times, everywhere.

I remember my father crying, reading right to left, looking for explanations in the paper and ink voices of ancient prophets. Words filling his throat that only housed pained groans, hushed screams: the sound of one catastrophe produced by the echo of another catastrophe.

Hear it now as I still hear it.

My father chasing an explanation for the end of his world in the forms of the world’s beginning.

Before long, my father begins to detest the false comfort of other religions (the multitude of Eastern gods and Western saints and that oh so sci-fi notion of Paradise, that other utopian “planet” that comes after this planet, I think now) and to rage in front of churches fuller all the time with the Great Depression. Dumps run by fake-orgasmic priests swearing, with a regularity beyond irritating, to have been “touched by God,” as if God were some kind of specially endowed, all- powerful playboy. And so, all of sudden, everyone is claiming they’ve witnessed something or someone and my father ceaselessly condemns this socialization of miracles. Visions like a plague, for someone who thinks that miracles shouldn’t be massive and popular, but individual and occasional and capable of carefully selecting the site and eyes and body where they come to rest.

That clamor of lies and the incontrovertible truth of the Jehovah’s absence. It’s then that he reads what the Spanish cabalist Abraham Abulafia wrote about something called Tikkun Ra, or “the reappearance of the world,” and disclaimer: I’m not entirely sure about the meaning of this term or of the other cabalistic ideas I refer to here. I cite things from memory that I don’t remember precisely but won’t ever be able to forget.

I remember perfectly, yes, my father studying those symbols. The furious intensity of my father staring at a book. The energy that seemed to enter through his eyes and shake his entire figure, which a pulp illustrator of the day would’ve drawn as a mad scientist with sparks and lightning bolts emanating from his burning brain.

I remember my father telling me what the books told him.

I remember my father explaining to me that the mystics believed that in the beginning, the Divine Light of God, keeper of all things good, was preserved inside one or multiple sacred vessels. But, as the glimmers and cracks of evil had also already appeared in the world, the vessels couldn’t contain that splendor and they shattered. And the beneficent Divine Light broke into countless fragments that fell like crystal rain across the world. And, as they spread, swept by the winds and the slow but inexorable inertia of the planet’s rotations, those divine fragments changed sign and transformed into all the horrible and monstrous things that have happened ever since. Diseases and wars and cataclysms. The mystics, my father tells me, maintain that the task of mankind is to reunite all those malignant fragments by doing good deeds. Transforming them back into benevolent material and reassembling them, like restoring a broken statue to its original whole. The perfect good. The indivisible splendor of the creator.

Tikkun Ra, thought my father.

And it’s then, I believe, that my father decided that I’d be one of those small, lost pieces: something evil only in appearance (because he was unable to avoid associating my arrival with my mother’s departure), but in whose fate and origin lived, barely hidden for those who knew how to look, part of the original and absolute root of the best and first good news.

My father also read (and only then did he feel he’d grasped its true significance and importance) about Tzimtzum. That constriction—the Kabbalah explains—experienced voluntarily by God. God contracting and compressing himself and renouncing his own infinite essence to allow for the existence of a conceptual place: chalal panui, a space where a world could exist independent of Him. In a way, God made Himself into the perfect reader so that we’d be imperfect yet fertile writers.

Tzimtzum means, I believe, “to conceal Himself from the beings He created, to let them exist as tangible creatures, instead of over- whelming them with His perpetual and infinite presence.” So God limits Himself—puts boundaries on His divinity—withdrawing with- out disappearing so that there might be something outside of Him. What Solomon Goldman was never able to fully understand was if God’s diminished size implied a relative reduction of His power or, to the contrary, turned it into a far more potent concentrate. If God’s self-limiting weakened Him, then maybe man’s corresponding role was to occupy that chalal panui and attempt to resemble God. Or, perhaps, to the contrary, to commit human errors over and over to emphasize the imperfection resulting from the partial yet decisive withdrawal of the Lord and Master of all things and thereby provoke Him to come back to make order of the chaos. Solomon Goldman didn’t know what to think. Both possibilities seemed logical. That’s the problem with the Kabbalah: unlike other sacred texts, it doesn’t offer answers, just pieces with which to assemble an answer. It’s not a compendium of infallible instructions. In the end, the true manual is mankind, the reader, the interpreter and assembler of all the loose pieces. Man approaches God through reading. And God—this god— is a man with deep faith in mankind. That’s why He’s left them alone and only in certain moments does He reappear, proud, to punish some blunder He deems incomprehensible. Some ignorance unjustifiable in creatures as magnificent as His, in beings artificially designed in His image and semblance. At times, the reason for His presence is easy to comprehend. Floods, commandments, and sharp shadows that cut off the lives of firstborn children and sacrifices that, sometimes, at the last second, are halted or neutralized. Events and marvels woven with the transparent texture of legends or fables.

But Solomon Goldman felt that he was the protagonist of some- thing else, something far more complex. Something only accessed, or suffered, by the enlightened. Because God didn’t halt the rhythm of Fair Sarah’s death. God allowed Fair Sarah to cease existing and allowed him to survive her.

So would his mission be to reunite the pieces of the broken ves- sel, to reunite the lost exhalations of the Divine Light?, my father wondered. One night, after explaining all of this, he asked me that terrible question, and I really didn’t get it. I didn’t even realize that my father was in trouble, that his was another kind of illness. But I intuited how all of that would seem curiously similar to what I’d read later in science fiction magazines.

Religions are, all of them, early forms of science fiction: sudden flashes, flying, above and below, visitors from galaxies on the other side of infinity, appearing and disappearing. It doesn’t matter which planet: the story is always the same and it’s powered by the volatile fuels of love and death and an inferior faith in something superior: man creates God so that God creates man. And then they discover they cannot deactivate each other and that both, in a way, have turned into each other’s Frankenstein’s monster. Thus, man believes in God so he can do as he pleases in His name and God believes in man so He can blame him for all His mistakes.

At some point (I realize now that I refer to him, indistinctly, as my father or as Solomon Goldman, as if I were trying to divide him in two without having to break him into pieces more dark than light; as if in the one or the other I might find, barely hidden, the explanation for his madness) my father Solomon Goldman begins to talk to me about “aerial beings,” about “stellar powers,” about “portals,” and about “dimensions.” And about how I—having been on the threshold of death without being wounded too deeply, having almost come back from the other side—was the key that’d open the cell where he’d find my mother, Fair Sarah, a prisoner.

And it’s not that I believe him, but some part of me wants to believe him. Some part of me needs to believe him, because his visions are so much brighter and livelier than reality’s faded hue. And because, for the first time, in his delirium, in the magical properties he confers on me, I feel that my father loves me as a son, that he’s proud of me. So, one night I clearly hear the whirr of a machine outside my win- dow and believe I see them, just landed, with fierce smiles and tracing symbols in the garden soil with swords of light. Timeless angels held aloft by the wind of other “planes of existence,” their wings exuding a strange, immaculate glow. The next morning I wake up possessed by terrified happiness. Thinking I’d come to believe in what my father believed, convinced that from that moment on a new life would begin for me.

A life of true lies.

A false existence where I’d find myself forced to remember every- thing I said because—if I were to tell someone what I was almost certain I’d seen the night before—I’d be instantly written off as a liar. And liars have the terrible obligation of remembering everything they’ve said. Each and every lie. And that’s how they wind up arriving at that crystalline instant where the lies are enough to completely cover the surface of the planet of their true lives. The lies cover everything like a deadly virus imported from the far reaches of the universe, and for which there’s no cure or comfort. And when there’s nothing left to infect, when everything has been devoured, the lies begin to devour each other.

My lies, I realize, will be very different from the lies of other children. Children who lie to cover up a naughty deed.

I, on the other hand, will lie because, for me, all truth will seem far worse than any falsity.

For me, all truth will be unbearable.

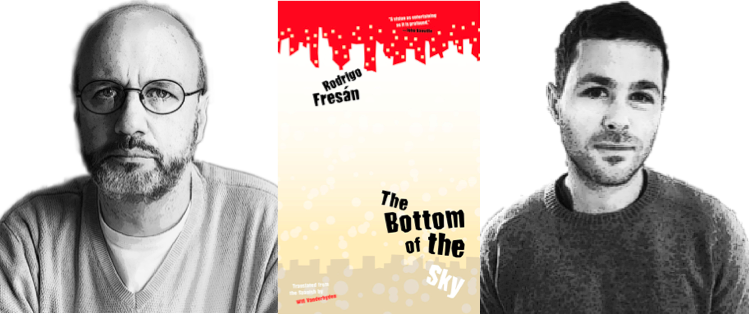

Rodrigo Fresán is the author of ten works of fiction, including Kensington Gardens, Mantra, and The Invented Part, the latter two of which are publishing by Open Letter books. A self-professed “referential maniac,” his works incorporate many elements from science fiction (Philip K. Dick in particular) alongside pop culture and literary references. According to Jonathan Lethem, “he’s a kaleidoscopic, open-hearted, shamelessly polymathic storyteller, the kind who brings a blast of oxygen into the room.” In 2017, he received the Prix Roger Caillois awarded by PEN Club France every year to a French and a Latin American writer.

Will Vanderhyden received an MA in Literary Translation Studies from the University of Rochester. He has translated fiction by Carlos Labbé, Edgardo Cozarinsky, Alfredo Bryce Echenique, Juan Marsé, Rafael Sánchez Ferlosio, Rodrigo Fresán, and Elvio Gandolfo. He received an NEA Fellowship to work on The Invented Part.

This excerpt of The Bottom of the Sky is published by permission of Open Letter Books. Copyright © Rodrigo Fresán, 2009. Translation copyright © Will Vanderhyden, 2018.

Published on June 5, 2018.