Los olvidados de los olvidados: Un siglo y medio de anarquismo en España

Los olvidados de los olvidados: Un siglo y medio de anarquismo en España

By Carlos Taibo, with illustrations by Jacobo Pérez-Enciso

Publisher: Catarata

Recommended by Louie Dean Valencia-García

Los olvidados de los olvidados: Un siglo y medio de anarquismo en España [The Forgotten of the Forgotten: A century and a half of Anarchism in Spain], by Carlos Taibo, a professor of political science at the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, is a sympathetic, but well-done, introductory history to anarchist/libertario movements in Spain. With charming illustrations by Jacobo Pérez-Enciso, the book is written to describe anarchist movements to an educated audience because of the author’s belief that Spain’s history of anarchism has been largely ignored, or worse, folded into a Republican narrative (Taibo firmly claims “anarchists were not Republicans.”) The book simultaneously dispels with myths associated with anarchism—the first myth being that anarchists were against organizing. Taibo argues practitioners of anarchism believe in “autogestion”—self-organizing—in a way that allows humans to “collectively direct all economic activities and social relations, without the necessity of business owners and foremen, uses decentralized and federal bases.” Often, histories that do deal with the history of anarchism in Spain delve into what can be a difficult to enter world filled with abbreviations ad infinitum (CNT, FAI, UHP, CEDA, etc.) Taibo’s well-organized and gorgeous book avoids the alphabet-soup traps that often drown most works of its kind. The author skillfully narrates the origins of anarchism in the nineteenth century, describes its successes, and recounts its battle against authoritarian fascism. In particular, the author’s accounts of the women’s anarchists group, “Mujeres Libres,” which had 150 chapters and more than 20,000 members, such as Amparo Poch, Mercedes Comaposada and Lucía Sánchez Saornil, is particularly welcomed. Los olvidados de los olvidados is a visually rich and clear history of anarchism in Spain and provides an excellent bibliography for the newly initiated to that history.

Laboratory of Socialist Development: Cold War Politics and Decolonization in Soviet Tajikistan

Laboratory of Socialist Development: Cold War Politics and Decolonization in Soviet Tajikistan

By Artemy M. Kalinovsky

Publisher: Cornell University Press

Recommended by Samantha Lomb

Artemy Kalinovsky’s new book examines post war Soviet Tajikistan, situating Soviet industrial, educational, welfare and agricultural development projects within the broader historiography of post-colonial economic developmental projects in the Third World. The Soviet Union and the US, and later, the People’s Republic of China competed for allegiances in the developing world by offering advice and resources to post colonial leaders. The Soviet Union’s semi-colonial periphery proved to be a fertile testing ground for such large-scale development projects, which Kalinovsky compares to European colonial and post –colonial development projects in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Additionally, the local Tajik elites took advantage of the USSR’s interest in the Third World to argue for large-scale investment in development projects in primarily rural and agrarian Tajikistan. Like leaders of post-colonial states they too hoped that dam construction, industrialization and education would transform Tajikistan and make the Tajik people modern subjects. Soviet projects were not just designed to modernize the physical landscape but the people as well. The Russian concept of kul’turnost’ (culturedness), a concept that overlapped with many elements of European modernity, or specifically notions of European middle-class modernity, was imprinted in Tajik modernization campaigns as well. But, like other Soviet notions, it was surprisingly mutable, with local elites often creating their own definition of cultured behavior. Laboratory of Socialist Development grapples with how universal ideas were negotiated locally and ultimately reshaped.

Throughout the book, Kalinovsky demonstrates how the modernizing paradigm changed, as large-scale investment failed to yield the hoped for result for both European and Soviet modernizers, who sought to recreate European style modernity in the Third World and Central Asia. Instead they often wound up marginalizing indigenous communities and destroying livelihoods. He offers comparisons with experiences in countries such as India, Iran, and Afghanistan, and considers the role of Soviet and Tajik intermediaries who went to those countries to spread the Soviet vision of modernity to the postcolonial world. Laboratory of Socialist Development provides the reader with a new way to think about the relationship between the Soviet, primarily Russian, center and its Turkic periphery as well as the interaction between Cold War politics and domestic development.

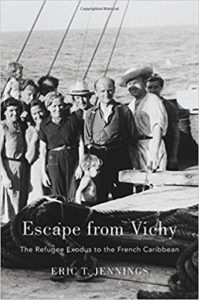

Escape from Vichy: The Refugee Exodus to the French Caribbean

By Eric T. Jennings

Publisher: Harvard University Press

Recommended by Hélène B. Ducros

As the world faces a critical moment in the history of migrations, this book tells the story of a collective transatlantic exodus during WWII from France under the collaborationist Vichy regime to the French and Vichy-controlled Caribbean island of Martinique. Between October 1940 and May 1941, after other maritime routes had been closed or made impracticable, many were those who reached Martinican shores while escape was still possible. They were Jews, but also communists, intellectuals, artists, refugees from Francoist Spain and other European countries under fascist rule, all deemed “undesirables” by the administration. Eric Jennings tracks not only their procedural context of departure, but also the journey itself and the conditions of reception. This captivating book retraces various paths taken and positions individual trajectories in the wider scope of a geopolitical history linking Europe to the Americas, teasing out questions of agency, administrative responsibilities and complicities. Among Jennings’ passengers, anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, poet André Breton and artist Jacqueline Lamba, revolutionary Victor Serge, avant-garde photographer Germaine Krull, screenwriter Jacques Rémy/Assayas and cinematographer Curt Courant, or Cuban artist Wifredo Lam were among a crowd of illustrious characters who, along with less illustrious companions, boarded nineteen vessels in Marseille and headed to Fort-de-France, in a race against the clock for fear of an interruption of the Marseille-Martinique route.

Through these experiences, the book underscores how French colonies were incorporated in WWII relocation schemes as refugee/exile destinations, as well as the role of the US in opening and blocking certain escape routes in the region. It also highlights the role of networks, word-of-mouth, serendipity, mere luck, débrouille, or determination in successful evacuation. Who got on these boats was the result of many factors, often fortuitous and impossible to plan for, including the fact that Vichy itself was not an entirely coherent political space in which everyone strictly obeyed the Interior Ministry, whatever the reasons were for complicit behaviors that saved lives. The account of the transatlantic passage and time spent at sea, immortalized by artists, photographers or writers present onboard, leads to a reflection on the uncertainty and risk of migratory journeys. The second part of the book, emphasizing the encounter dimension of migration, describes the Martinican stay (including a meeting between Césaire and Breton) and life in the internment camps where refugees were detained, confirming that the migration experience does not end when destination is reached. As they grappled with a racist and violent society, over-zealous Pétainistes, political purges, but also resistance activities that would lead to Martinique freeing itself from Vichy in 1943, the book’s protagonists contribute to the reconfiguration of post-colonial studies through a better integration of WWII as a shaper of decolonization.