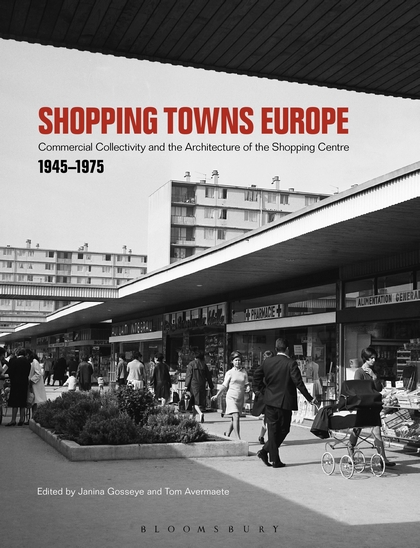

Shopping Towns Europe: Commercial Collectivity and the Architecture of the Shopping Centre by Janina Gosseye and Tom Avermaete

This is part of our special feature, Contemporary Urban Research in the European City.

This is part of our special feature, Contemporary Urban Research in the European City.

Two decades ago, historian Victoria de Grazia argued in the book Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through 20th-Century Europe (Belknap, 1995) that the spread of American-style consumerism to postwar Western Europe was mainly driven by an often unwitting collaboration between state officials and private parties who, “initially acting solo, even at cross-purposes, [ultimately] operated with the impeccable synchronicity of a movie dance routine, resonating with that enthusiastic unity of purpose called the “national interest” that was the hallmark of the Cold War consensus.”[1] Since then, scholars have revisited portions of De Grazia’s argument – notably, a recent volume has qualified the existing view of the Americanization of postwar Europe, noting that the continent’s consumer societies influenced each other as much as they were influenced by American ways.[2] Recent studies have also offered more targeted insights into how various commercial imports such as the supermarket took hold in mid-century Europe. Yet, for all of this scholarship, warn Janina Gosseye and Tom Avermaete, editors of Shopping Towns Europe: Commercial Collectivity and the Architecture of the Shopping Centre (Bloomsbury, 2017), one socially transformative import – the shopping center – has not received similar scrutiny. This, they argue, has seriously distorted our historical understanding of how the built environment shaped postwar European modernity, an understanding focused overwhelmingly on welfare state-driven public (especially housing) projects while virtually ignoring the impact of commercial spaces developed by a diverse array of private as well as public actors.[3]

Gosseye and Avermaete’s collection aims, by its own account, to “redress the historiographical imbalance as it widens the perspective beyond state-driven initiatives and engages with commercial modernity…[and] demonstrates the profound impact that the shopping center has had on everyday life in postwar Europe.” In particular, this book argues that if, as is by now familiar, state-led modernization generally rested on and reproduced belief in a “weighty contract between society and individual,” other forms of modernization also existed that were driven not by social solidarity but a pursuit of individual as well as collective pleasure through consumption. Put another way, Shopping Towns Europe suggests that the logic of the welfare state may have been central to, but was by no means the sole driving factor behind, postwar European modernity’s advance, and if anything, it existed in dialogue with a host of other, often far more individualistic motivations that found expression, “[not] through novel dwelling practices or government-funded spaces…but rather through spaces imbued with the tantalizing logic of mass consumption.”[4]

Shopping Towns Europe advances these arguments across sixteen individually authored chapters that appear organized into three sections, each focused on a different aspect of the multidirectional relationship between state, merchants, architects, and consumers that is the volume’s overarching subject. The contributions in this book’s first section, which is titled, “Urbanism harnessing the consumption-juggernaut: Shopping centers and urban (re)development,” speak strongly to the hybrid public-private character of postwar urban development. Chapters examining France, Brussels, Helsinki, Rotterdam, and Skopje illustrate how state actors invited and used privately-run shopping centers to anchor new or newly-rebuilt urban areas. The book’s second part, “Constructing consumer-citizens: Shopping centers shaping commercial collectivity,” explores the shopping center’s role in a larger mid-century European effort to chart a third way between American capitalism and communist economic planning by shaping “consumer citizens” who operated within a Soziale Marktwirtschaft or “Social Market Economy.” This section’s six chapters, which focus on cases as diverse as Milton Keynes, Stockholm, Italy, and socialist Croatia, explore how urban planners, architects, and businesspersons spearheading these projects aimed not only to anchor the urban surroundings, but to promote specific kinds of consumer – and by extension, social-civic – behavior in shoppers. As such, this book joins the aforementioned wave of scholarship that has stressed the agency of postwar European consumer societies in the face of American cultural hegemony, and which includes recent collections on local reception of the appliance-centered American kitchen and on European commercial innovators’ selective appropriation of U.S. practices and technologies.[5] Finally, this volume’s third section, “Shifting forms of shopping: Between dense and tall and the low-slung (suburban) shopping mall” underscores and further complicates the arguments previously put forward: cases studies of Frankfurt’s Main-Taunus-Zentrum and of regional shopping center development outside of 1970s-1990s Barcelona, to cite two examples, underscore how broadly Europe’s shopping malls could differ from one another and their American archetype, particularly when located in urban centers rather than the peri-urban areas favored in the United States.

As a history of the beliefs, expectations, motives, and modus operandi of the architects and urban planners who masterminded postwar Europe’s wave of shopping center construction, this volume is superb. It considers not only a range of national cases on both sides of the Iron Curtain, but also includes analysis of a wide range of actors who, depending on the particular social and political circumstances of a given case study, were implicated to varying degrees in the creation of these commercial venues. Chapters such as Inderbir Singh Riar’s study of the Candilis-Woods architectural firm’s conception for Frankfurt’s Römerberg shopping complex, as well as individual contributions from volume editors Janina Gosseye and especially Tom Avermaete, which examine the creation of Milton Keynes’ commercial center and architect Claude Parent’s work developing several shopping centers in mid-century France, respectively, offer a close-up view of the often deeply intentioned choices these buildings’ designers made. Others focus on the work of the usually government-affiliated urban planners with whom these architects often partnered, including Juhana Lahti’s analysis of how shopping centers came to figure centrally in the drawing up of 1950s-1970s Helsinki’s urban layout master plan, as well as Jasna Mariotti’s chapter on how urban planners redesigned Skopje’s urban core around new commercial forms after a 1963 earthquake destroyed much of the city center. This set of approaches is especially welcome, as the majority of the contributing authors are by training scholars of architecture and urban planning, lending the book a perspective that the historian may at points find refreshing novel – notable examples include Avermaete’s attention to the architectonic thinking behind Claude Parent’s use of inclined planes in the planning of the Ris-Orangis shopping center built between 1967 and 1970, and Steffen de Rudder’s analysis of the at-times unconventional choices and practical rather than “high architectural” aims that shaped the design of Frankfurt’s Main-Taunus-Zentrum rural shopping mall.[6] At the same time, various chapters also cast their net more broadly, taking the larger planning, architecture, and commercial professions’ views into account through scrutiny of industry periodicals such as Germany’s Bauwelt and Sweden’s Arkitektur. And in some instances, authors have dipped into the especially challenging waters of determining public reaction to these buildings and the often expansively-conceived social aims inscribed therein.

Unfortunately, this dimension of the book is also a source of possible criticism, which concerns its treatment of the consumers who through their experiences of, around, and inside these shopping centers represented their – and by extension, this volume’s – raison d’être. Though this is perhaps to be expected of a work of architectural history, from the cultural historian’s perspective the otherwise excellent contributions in Shopping Towns Europe tend to focus overmuch on authorial intent: that is, on the methods and motives that shaped the actions of urban planners, architects, businesspersons, and government officials as these parties undertook the many decisions that gave form to the titular shopping towns. The volume’s contributors pay less attention to the people who through their interactions with and mapping of meaning onto these built environments represented an indispensible stage in the process by which, to cite one of the volume’s central themes, patterns of consumer behavior were reconfigured.

In some cases, such as Jennifer Mack’s chapter on Stockholm’s Skärholmen shopping center, the experiences of ordinary shoppers receive their due. Initially, this chapter focuses on planners’ hopes of fostering both prosperity and civic interaction through construction of a shopping mall that would also serve as a collective leisure space, but then shows how, at the level of consumer reception, these hopes were quickly frustrated amid public backlash against the unnecessary over-consumption and ‘passive’ shopping many believed the space encouraged. Similarly, Gosseye’s study of efforts to anchor newly-built Milton Keynes around a shopping center in 1970s England reveals that while planners expected the new public space to cultivate a sense of community among locals, these instead condemned the space’s conflation of social interaction with consumerism and balked at tax increases they believed had financed the project. And in both of the above cases, the authors recover ordinary consumers’ voices by means of a staple of social and cultural history – scrutiny of local press coverage.

Other contributions, unfortunately, are not so well-balanced. Despite its virtues, Avermaete’s study, for instance, only briefly addresses reception as it concludes, noting both that Ris-Orangis generated considerable initial public interest, but was ultimately not socially and culturally transformative as Parent had hoped – points that significantly impact this story and so should feature more centrally. Singh Riar’s chapter on the Römerberg center does not address public responses at all. Admittedly, this critique may be slightly unfair, as many of the book’s chapters focus explicitly on builders’ philosophies and aims. Still, the reader is left with an incomplete view of the process of culture creation that contributors otherwise ably show postwar Europe’s city planners and architects to have undertaken. At the end of the book, one is left wondering, “…and how did consumers feel about all of this?” A skeptic might suggest that some of the grander ambitions that Candilis and others harbored were simply lost on shoppers; both more cultural analysis devoted to these consumers and their societies, as well as further recourse to the methods of business history – some notion of how and how much consumers spent in these establishments, for instance – would lend these chapters greater authority and complete (or complicate) the picture in likely fruitful ways.

With that said, many of the contributions in Avermaete and Gosseye’s collection show a laudable awareness of the political contexts, motivations, and pressures that conditioned the urban development projects they examine; this is especially welcome in the case of chapters like Mariotti’s as well as Sanja Matijević Barčot and Ana Grgić’s examination of the politics behind the introduction of the shopping center model in 1960s socialist Croatia, which in particular echo research in Koenker and Gorsuch’s The Socialist Sixties that explores the ambitions to a new socialist ordering of society that lay behind the 1960s-1970s Soviet construction of the worker’s colony of Tol’iatti.[7] As in that volume – yet also both in the very different contexts of a pair of constituent republics within geopolitically non-aligned Yugoslavia, and with the focus more specifically on the development of commercial architecture rather than the wholesale construction of and mapping of meaning onto an entire settlement – these authors underscore the thoroughly political nature of the built environments in which individuals’ personal experiences take shape. It is for instance fitting that, writing about precisely the period when critical theorists Jean Baudrillard and Guy Debord were formulating incisive critiques of the spectacular mass consumerism that had become the ontological basis for lived culture in the West, contributors Jennifer Mack and Dirk van den Heuvel point to the often thoroughly political aims behind the creation of fully immersive mass consumer spectacles at Skärholmen and Rotterdam’s Lijnbaan center. Indeed, Tom Avermaete’s individual contribution to the volume gestures especially clearly to this larger sociopolitical backdrop. As his opening gambit, Avermaete selects the iconic postwar European literary critique of the postwar’s empty consumer spectacles, Georges Perec’s novel Things: A Story of the Sixties (1965), arguing that the shopping centers architect Charles Parent built with the aim of modernizing mid-century French social relations by bringing shoppers together around new shared consumer experiences that cut across old class lines, ultimately became epistemological “prisons of plenty” that French consumers, like Perec’s protagonists, willing shut themselves in and defended.[8]

A final welcome aspect of Gosseye and Avermaete’s collection is, as alluded above, its wide field of vision: as the editors put it, the book seeks to examine Europe broadly, from Barcelona to Helsinki, and from Milton Keynes to Skopje. This diversity is appreciated especially because the book examines not just well-trodden France, Germany, and Britain, but a number of consumer societies that straddles competing world systems: Soviet East and capitalist West, in the case of Helsinki; Second World and non-aligned Third (Skopje and Croatia); and – of personal interest to this reviewer – late Franco-era and post-Francoist Spain.

Though it is limited in some ways by the relatively narrow analytical approach taken in some chapters, then, Shopping Towns Europe is ultimately a methodologically refreshing intervention that nevertheless manages to be entirely part of an ongoing historiographical moment. This is very much to its credit, and the novel perspective it offers is likely to prove enlightening to historians of modern architecture, of mass consumption, and most especially of Modern Europe.

Reviewed by Alejandro J. Gomez-del-Moral, University of Southern Mississippi and University of Helsinki, Finland

Shopping Towns Europe: Commercial Collectivity and the Architecture of the Shopping Centre

Edited by Janina Gosseye and Tom Avermaete

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Hardcover / 256 pages / 2017

ISBN: 9781474267403

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on May 1, 2018.

[1] Victoria de Grazia, Irresistible Empire: America’s Advance through 20th-Century Europe (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2006), 7.

[2] Per Lundin and Thomas Kaiserfeld, eds., The Making of European Consumption: Facing the American Challenge (London, New York: Palgrave Macmillan), 2015.

[3] Janina Gosseye and Tom Avermaete, “Shopping Towns Europe, 1945-1975”, in Janina Gosseye and Tom Avermaete, eds., Shopping Towns Europe: Commercial Collectivity and the Architecture of the Shopping Centre, (London, New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017),

[4] Gosseye and Avermaete, “Shopping Towns Europe”, 3.

[5] See Ruth Oldenziel and Karin Zachmann, ed., Cold War Kitchen: Americanization, Technology, and European Users (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009); and, Lundin and Kaiserfeld, The Making of European Consumption.

[6] Tom Avermaete, “Collectivity in the prison of the plenty: The French commercial centres by Claude Parent, 1967-1971”, in Gosseye and Avermaete, Shopping Towns Europe, 115-117; and, Steffen de Rudder, “The shopping centre comes to Germany: Frankfurt’s Main-Taunus-Zentrum at the crossroads of mass-motorization and retail economics” in Gosseye and Avermaete, Shopping Towns Europe, 200-202.

[7] Lewis Siegelbaum, “Modernity Unbound: The New Soviet City of the Sixties”, in Anne E. Gorsuch and Diane P. Koenker, eds., The Socialist Sixties: Crossing Borders in the Second World, (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 66-83.

[8] Avermaete, “Collectivity”, 110-111, 117-118, 121.