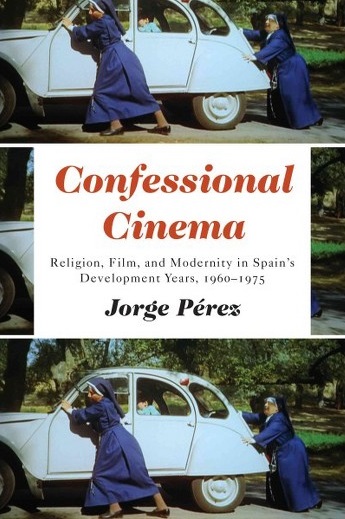

On the cover of Jorge Pérez’s Confessional Cinema, a couple of catholic nuns in their habits are hard at work pushing a Citroën 2CV along a park road with a child hanging on in the back seat. Spanish film aficionados will immediately recognize the image as a frame from Pedro Lazaga’s 1967 comedy Sor Citroën; some may even remember that in that particular sequence, it was the elderly, out of shape Sor Rafaela (played by Rafaela Aparicio) who had to push the out-of-gas car for five kilometers to reach the nearest service station. That image (and the entire sequence) encapsulates many of the tensions, contradictions, and paradoxes of late-Francoist Spain, the Spanish path toward modernity, the Spanish Catholic Church, and Spanish religious cinema of the so-called development years. On the one hand, the cover image is a testimony of the growing mobility of Spanish society and the mechanization of life, as symbolized by the automobile, while the motorized nuns embody the changes of the Church promoted by the Vatican II Council. On the other hand, the precariousness of the nuns’ predicament—with the elderly Sor Rafaela (symbolizing tradition) forced to push a car that has run out of gas (a car that was neither very powerful or reliable to begin with)—serve, along with Sor Tomasa’s inexperience and dangerously limited driving skills, as a very telling comment on the frailty, the shortcomings, and the uncertainties surrounding the modernization process at that point in time. It also shows that mainstream Spanish comedies of the period were willing and able to convey those contradictions in a rather open, even provocative, manner.

Confessional Cinema—Pérez’s second monograph after Cultural Roundabouts (2011), and his third volume overall following the co-edited collection of essays The Latin American Road Movie (2016)—explores a fundamental area of Spanish culture and film that had not yet been appropriately studied, partly because religion remains a very sensitive topic in Spain, and partly because of many critics and scholars’ own prejudices. The book evolves from a couple of core ideas: one, that in the last years of Franco’s dictatorship, religion ceased to be a vehicle of legitimation of the regime to become an agent of resistance and a promoter of democracy; and two, that mainstream commercial cinema understood and embraced religion’s new role more lucidly and in more constructive ways than most of the avant-garde, anti-Francoist filmmakers did. Those points are as intriguing as they are provoking, seeing as, for decades, most of contemporary Spanish literary, film, and cultural scholarship has been rather uncritically perpetuating a set of received, negative notions and attitudes about religion, the Church, and cine religioso. Pérez’s book is most commendable for the comprehensive, thoughtful, balanced approach that it takes toward those issues and toward the films it studies.

Confessional Cinema is divided into four chapters, and includes an introduction and a conclusion. The very thorough introduction reflects on Spanish film, religion, and the Desarrollismo period (1960-1975), and presents the crucial questions of the book; makes a compelling case for the importance of religious cinema in those years and for the need to study it from a new perspective; examines the concept of “religious film;” delves into “the spirit of Catholic capitalism,” paying particular attention to the role of the Opus Dei in the technocratic phase of Francoism as well as to the importance of “economic theology” through that same period. Chapter 1 focuses on hagiographic films of the early 1960s, some of which served as religious reassurances vis-à-vis the changes and the challenges of the emerging process of modernization, whereas others provided commentaries on the transformations within the regime itself. Chapter 2 explores a range of films within the confessional comedia del desarrollismo sub-genre and examines the various ways in which those comedies addressed, and adapted to, Vatican II’s recommendations as well as to the dynamics and contradictions of capitalist modernization. Chapter 3 concentrates on “nun films,” how those films articulate the Church’s tensions resulting from the Vatican II-inspired transformative process, and the ways in which they comment on the changing status of women in Spanish society of the time. Chapter 4 analyzes films by directors of the Nuevo Cine Español movement, including Basilio Martín Patino and Carlos Saura, among others; the chapter shows how those directors’ criticism of religion and of the Catholic Church’s support of the Franco regime was very much influenced by Luis Buñuel’s anti-clerical legacy and largely failed to grasp, or to acknowledge, the recent transformations in the Church as examined throughout the previous chapters.

Pérez’s book considers an impressive number of films—more than fifty—many of which had not received enough, if any, serious critical attention until now. The film analyses are invariably superb, tremendously perceptive, and illuminating. It is surely not an exaggeration to say that, taken as a whole, the sections of the book devoted to Sáenz de Heredia’s films constitute the best body of criticism to be found in any existing volume devoted to that highly significant Spanish filmmaker. The many qualities of the volume are only emphasized by the very clear, concise, elegant writing style and by the tight, cohesive organization. In sum, this is an extraordinary piece of scholarly work, one that comes to fill a void that only an extremely small number of books, such as Elizabeth Scarlett’s excellent Religion and Spanish Film, prevent from being absolute. Coming at a time when the Catholic Church, under the inspiration of Pope Francis, is immersed in a period of significant transformations akin to those of Pope Juan XXIII and the Vatican II Council, Confessional Cinema is bound to be a most influential work and a fundamental referent in Spanish cultural and film studies for many years to come.

Reviewed by Jorge Marí, North Carolina State University

Confessional Cinema: Religion, Film, and Modernity in Spain’s Development Years, 1960-1975

By Jorge Pérez

Publisher: University of Toronto Press

Hardcover / 280 pages / 2017

ISBN: 9781487501082

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on April 17, 2018.