This is part of our special feature, Beyond Eurafrica: Encounters in a Globalized World.

France’s former French citizens of Algeria, the Pieds-Noirs, include one of Europe’s largest diaspora communities in the twentieth century. This diverse group of people settled in Algeria during the colonial years, and after one-hundred and thirty years of French colonial rule, Algeria fought for and won its independence in 1962. The seven-year war was traumatic for both the Algerians and the French living in the colony, and nearly one million people crossed the Mediterranean during and after the war to make a new home in France. Although the Pieds-Noirs were primarily French citizens, many had never set foot in France before. Some grew up speaking Spanish and other languages depending on their heritage and where they grew up in Algeria. The protracted war to keep Algeria French had grown deeply unpopular by the time this wave of migrants arrived in France, and many suffered discrimination because of the strain they placed on the larger coastal cities of France, such as Marseille. Because of the traumatic conditions of departure and arrival, two types of remembrance arose in the community: for the older generation of migrants, a nostalgic attachment to the homeland often labeled “nostalgérie” began to appear in literature and art, and for the younger generation who had trouble processing what they had just experienced and why, their memories of Algeria were often silenced or fragmented. This younger generation received much of their knowledge of Algeria and the pain of its loss from their parents and older relatives or as “post-memory” (Hirsch “Family Pictures” 8).

The creative works produced by the survivors themselves between 1962 and the mid-1990s tended to focus on beautiful recreations of a lost “Paradise” in North Africa.[1] As Lucienne Martini explains, this generation’s deep love for Algeria and their profound knowledge of the country is heavily expressed through landscape and sunlight in their works (21). Identity and homeland were inextricable. Though many Pieds-Noirs were able to return to Algeria as tourists revisiting their childhood homes in the 1980s, the Algerian Civil War of the 1990s cut off the community once more.[2] This new separation, France’s recognition of the memory of Algeria through a series of “memory laws,”[3] and the coming of age of Algeria’s younger generation of Pieds-Noirs during the 1990s brought about a shift in the community. The older generation of stalwart memory guardians was passing away, and the younger generation who had spent a large part of their formative years grappling with the war of independence, began to address the traumatic and painful memories of Algeria in their literature and art.[4] These works may still contain beautiful backdrops of a stunning country, but the landscapes are sometimes littered with cadavers and other fragments of traumatic events, which formed into a scarred memory.

The generation of children and young teens during the war—those too young to understand the war but not too young to see and feel it—as well as those who do not remember but who grappled with post-memory, take the central role in this article. How can the memory of Algeria, both beautiful and violent, be expressed in visual work? How is pain and confusion transmitted when the fragile memory of Algeria as homeland also demands a place? For many of the artists born in the late 1940s onward, layering provides a way to both scar over and highlight physical and psychological wounds. I will specifically examine the artwork of Nicole Guiraud and Patrick Altes to explore how the memory of Algeria is transmitted in contemporary French art. Guiraud suffered the violence of the war directly through a bombing which severed her arm, and Patrick Altes, bearing no nostalgia of his own, has had the memories of Algeria transmitted to him from both family and community. Both artists use layers to engage the personal within the collective traumatic memories of Algeria.

Nicole Guiraud

Nicole Guiraud was born in 1946 in Algeria and famously survived the Milk Bar bombing during the Battle of Algiers in September 1956.[5] Her father was seriously wounded and her left arm was amputated when she was ten years old. Guiraud was among several children who were injured that day, and she uses her artwork to confront this traumatic memory along with many others she endured during the war. She was a sixteen-year-old art student when she fled Algeria with her sister to start a new life in France at the end of the war in 1962. Guiraud underwent intensive psychotherapy to come to terms with her personal trauma, and she has become a spokesperson for victims of terrorism and the Pied-Noir community today. Her art, while highlighting personal wounds, also deeply engages with the scars borne by the Pied-Noir community in France. She is currently working on an exhibit in Fréjus, France to celebrate Pied-Noir art (March 30 to April 23, 2018) and she curates a Facebook group dedicated to Pied-Noir art and culture.

Guiraud’s artwork directly highlights both the physical and psychological effects of trauma. In her Survivre (Survival) exhibit commissioned by the city of Perpignan, France in 2012 to commemorate the end of the Algerian War, Guiraud articulates her own and others’ trauma in her art. Although the beauty of the Algerian landscape sometimes serves as a focal point, the country is also overlain with blood: slit throats, severed limbs, and dead bodies appear on backdrops of sandy beaches and garden paths. In the series “L’Algérie heureuse” (Happy Algeria), six verdant paintings of lush gardens seem to swallow up Nicole and her family members showing us a time that precedes her traumatic amputation, but also exposing dead bodies and bloodied paths. Then Guiraud creates beachscapes, which at first appear to depict happy children splashing in the water against a blue sky. As the eye lingers, however, it is slowly drawn to a bloodied torso and left arm seem to have washed ashore. In each series, an unnamed traumatic event has been inscribed on the previously joyful location, often providing a sense of surprise or shock for the unsuspecting viewer, as it must have done for the original witnesses of the trauma.

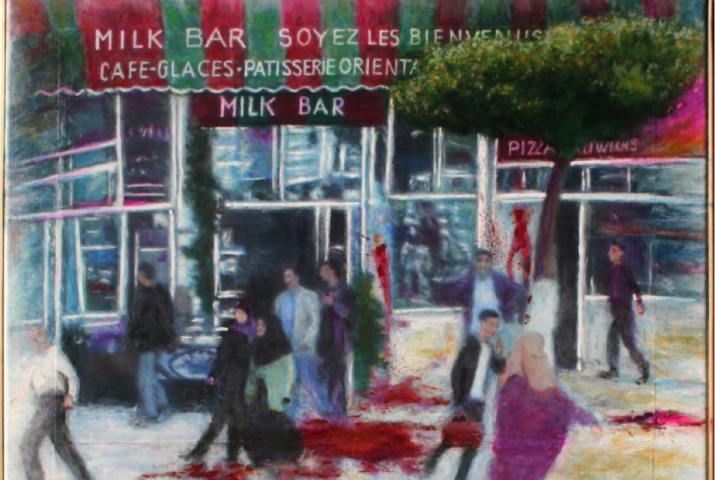

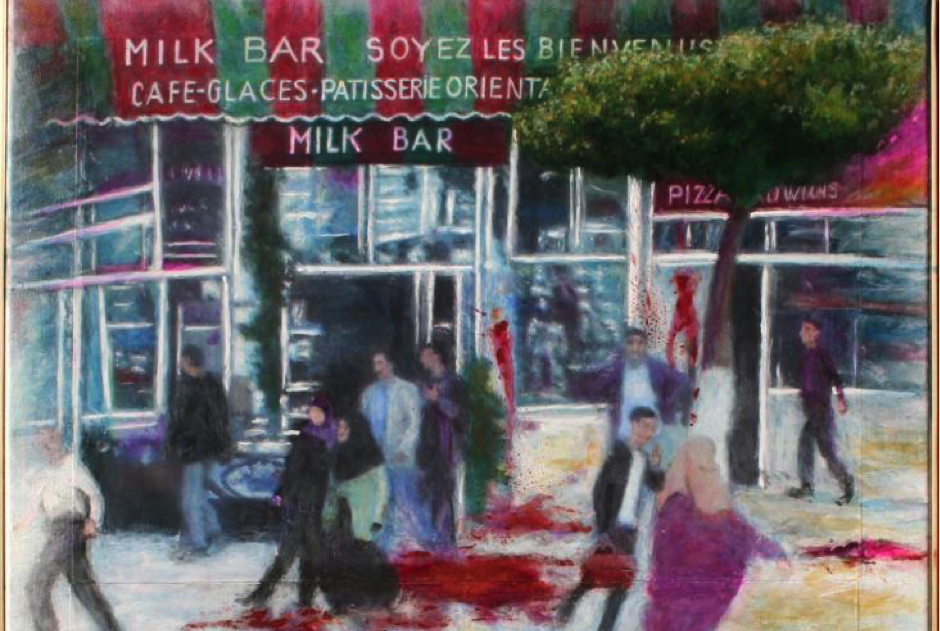

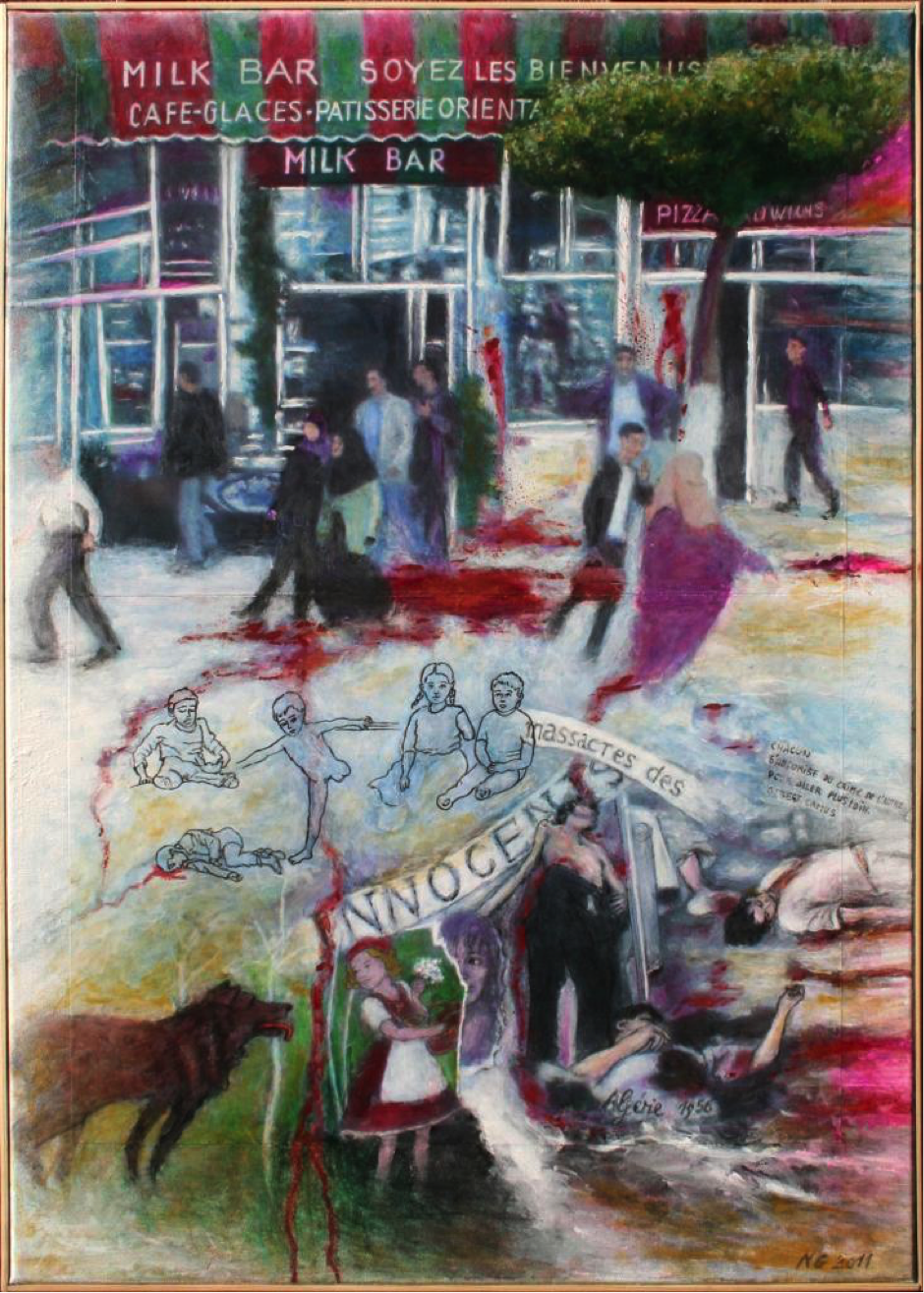

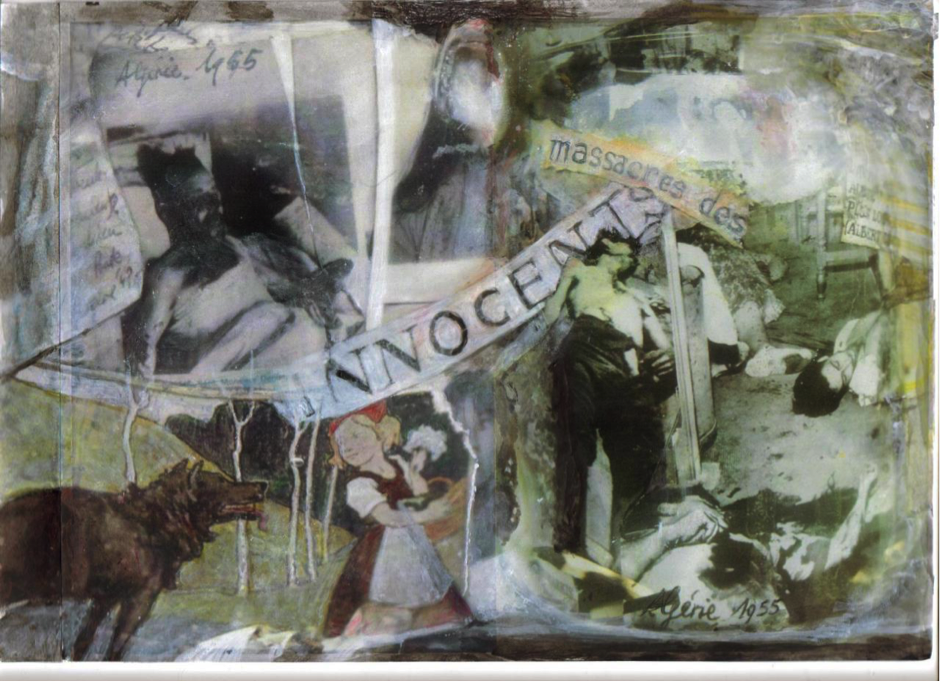

Guiraud’s works often go straight towards the traumatic events that shaped her childhood. As in the above examples where outlines of victims appear, Guiraud layers images in increasingly complex ways across the Survivre exhibit. “L’Algérie heureuse” gives way to “Attentat” (Bombing). Guiraud starts from a well-known black and white photograph of the Milk Bar after the explosion, and she traces it with smatters and drips of blood red (“Attentat Milk Bar” 25). This moment, which for Guiraud represents intense personal suffering, is translated without depicting any victims’ bodies, yet the traces of blood clearly call attention to violent wounds. In the painting Milk Bar, Guiraud recreates this scene, but this time, the maimed children – including Guiraud’s own amputated body – are traced over the image (Algérie 1962 cover, 97). Guiraud’s body is not drawn from memory, but from a recognizable photograph of the amputated children used in a medical journal L’Algérie Médicale.[6] While the photo represents the deepest level of suffering (and simultaneously survival) for Guiraud, by repeating a photographic image of a group of victims in the same outlined style she uses in the garden and beach images, she both creates a buffer around herself and articulates her own suffering with the same vocabulary she uses to represent other children’s suffering in the war. Similarly, when she presents the Milk Bar painting in her book Algérie 1962: Journal de l’Apocalypse, Guiraud places the real black and white pictures of dead bodies opposite her painting of the same victims. Through the juxtaposition of the real bodies with her interpretation, Guiraud enmeshes collective suffering into her own traumatic landscape (96-97) and contextualizes personal suffering into the deep community wounds. The words “Massacres des innocents” are embedded like bits of banners in the bottom half of the painting and the words are partially layered over the arm of one of the sketched maimed children (97). Because Guiraud does not directly identify whose bodies she is showing, it is only through intertextual study that we can recognize that the drawing of the “Innocent” is also a self-portrait.

The complex painting entitled Massacre des innocents (The Massacre of the Innocent), which appears in the Survivre exhibit repeats the bottom portion of the above “Milk Bar” painting. The same dead bodies in the same positions appear but in different circumstances. In Massacre, the top half of the painting is heavily layered and contains different images of victims, a blurred scene from the Milk Bar, fragments of handwritten letters, and the legible indication: “Algérie 1955.” Both paintings contain the same fairy-tale-like image of a wolf panting after a little Red Riding Hood in the lower left quadrant, but the images of dead bodies – some drawn, some painted to look like photographs – are layered on top of each other across the other three-quarters of the painting.[7] This Red Riding Hood appears to be walking along a river of blood, which emanates from the victims (Journal 104, Survivre 26-27). In between the fairy tale and the dead bodies, however, an intermediary image appears. The transition between the little girl and the first cadaver is made through the frayed and mostly obscured image of a woman, presumably Guiraud as an adult, centered below the words “Innocents.” The photo-like image of Guiraud’s face is torn so that one eye, half her nose and most of her mouth are absent. She is silenced against the dead bodies, unable to warn the perfect little child of what is ahead, and unable to escape this central position in the massacre. The intermingled bloodied bodies held in place by bits of letters and other debris overwhelm the eye while Red Riding Hood seems to be both the clearest and safest of all: she nonchalantly looks over her right shoulder to face her wolf among barren white trees appearing unaware of the kinds of death that lurk just ahead.

Guiraud’s many works repeat these same layering techniques, inscribing communal photos alongside the personal debris from her experiences in Algeria. From the seemingly peaceful garden and beach images to the highly chaotic scenes of the Milk Bar bombing, Guiraud is both central and effaced, and the trauma she depicts through the layers is both her own and her community’s. While Guiraud has been both physically and psychologically scarred from the war, she also creates a scarred depiction of Algeria through the various layers of wounded victims she piles into the frame – visible and buried under at once.[8]

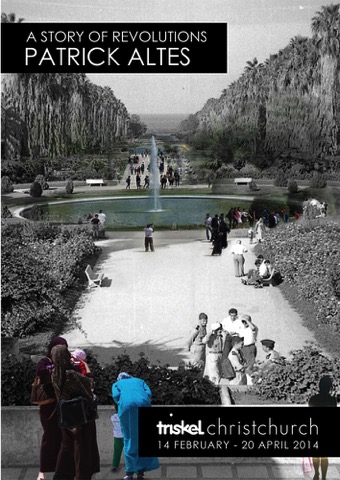

Patrick Altes

Patrick Altes was born in 1957 in Algeria after the war had begun. Unlike Guiraud, Altes’ wounds are not physical, and because of his age at the time of independence, he does not have a sense of proprietorship of this country. Instead, his experience of Algeria has been largely through the scope of independence, and he feels no right to mourn his homeland. He explains: “My ‘political engagement’” against the notion of colonialism has robbed me of my right to feel for the land where I was born and feel guilt at celebrating it. Were my passport Algerian, feeling nostalgia from my birth country when estranged from it, would be natural; with a French passport, it becomes suspect” (“A Story” Leverhume Trust). Because of this sense of separation, in the “A Story of Revolutions” exhibit, Altes does not rework his own images or memories of Algeria. Rather, he relies on photos from the broader community which allow him to investigate different relationships to the past because, “The transactional act of my request for photographs of someone’s private, personal history –and their selecting, handing them and giving me permission is in fact a dynamic exchange in the now where they share their personal history to an artistic exploration that encompasses past, present and future” (“A Story” Leverhume Trust). This exchange in the community calls to question the experience of remembrance across various points in time. It also allows Altes to avoid relying on his own memories of Algeria and to engage with the community and its inherited memories through his own critical eye.

Through these borrowed and recycled images, Algeria is portrayed through organized layers. Altes sometimes incorporates iconic photographic images of Algeria and then inscribes multiple experiences upon them to demonstrate a different kind of history – a fragmented and disjointed story of colonialism – rather than the solidifying picture many Pieds-Noirs have attempted to create of their pasts. His work more closely represents what Svetlana Boym would call reflective nostalgia which “does not follow a single plot but explores ways of inhabiting many places at once and imagining different time zones; it loves details, not symbols” (10). Furthermore, reflective nostalgia, “cherishes shattered fragments of memory and temporalizes spaces”(49). In an interview on the “A Story of Revolutions” exhibit, Altes confirms, “I seek to dissociate personal nostalgia from its political instrumentalisation as well as question the dominant and widely accepted historical and political narrative relating to this period of history. My work offers a thought-provoking and humanistic narrative challenging a dominant pied-noir discourse imbued with distorted myths and political point scoring” (“A Story” Creative Space).

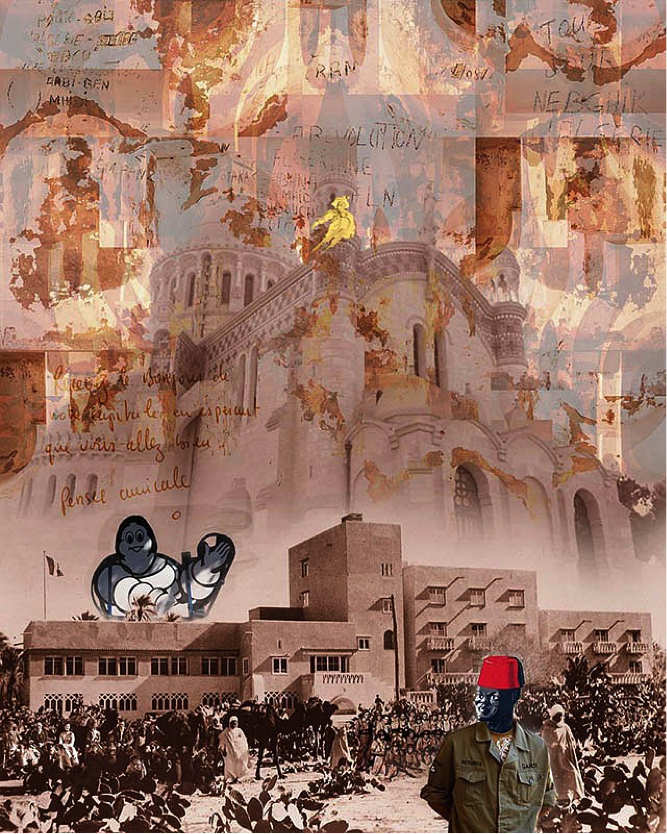

Layers are one way of highlighting the shattered fragments of memory and multiple temporalities of place in the present. In the print Des p’tits Gars bien d’chez nous (2013) Altes superimposes recognizable sites and postcard-like images, melding them into one frame that demonstrates the inherent tensions and oppression that result from colonialism. Faded in the upper half of the photo is the massive colonial landmark Notre Dame d’Afrique Basilica in Algiers. Fragmented and overlapped messages and images partially obscure the mammoth construction but it remains plainly identifiable. Along the top of the tableau, multiple negative photos are layered to form arched and flame-like patterns but the individual images are indecipherable. Words are scrawled, partially from a postcard message (“pensées amicales” or “warm thoughts” are clearly legible) and partially from liberation-inspired graffiti (“FLN” and “La Révolution” are written in block letters). In the top central portion of the artwork, a glowing man sits atop the church, not exactly where the Our Lady statue should be, legs askance. He is a ghostly historical figure watching over the “little guys” below. The otherwise watchful “Our Lady” has been so faded and layered over, the spectator would have to know she is there and then strain to find her. The bottom third of the artwork provides the foreground and it is filled with black and white postcard images: a modern rectangular government building with oriental patterned windows on the bottom floor is skewered with French flags. An army of soldiers sits in front of the building: spahis (Algerian mounted cavalry for the French army) with horses and camels, men in both traditional Arab and French attire, so many little images of people that they blend in with the trees and cactuses. On the left, the smiling Michelin Man (Le Bibendum) humorously looks down waving over the building at the throng of people with his neo-colonial intentions exposed. At the bottom right, a dark-skinned African man in an army green soldier’s uniform and a bright red chechia grins mischievously as he looks to his right but faces forward with his body. This image immediately recalls the French tirailleurs sénégalais, the African troops who served the French army in its wars regardless of their country of origin, but it highlights racial disparities in the colonies as the stereotypical figure stands diagonally opposed to the great white Bibendum.[9] The scene when viewed together is loud and chaotic, but the tones consist of muted metallics and faded oranges. Only the bright red cap stands out. The violence of colonialism is at once felt but not directly depicted. Unlike in Guiraud’s images, there is no blood, no cadavers, no apparent violence, but the multiple layers underscore the scars of colonialism that still remain in French memory. Art critic Stephen Clarke comments:

Underneath the surface of Altes’ pictures bubbles the hot lava of memory. The French colonists, displaced following revolution, hold on to their pictures; family snapshot photographs show their Eden, a past existing in the present. In many of Altes’ artworks these old photographs are displayed as thought bubbles poking through to the surface. Critical of this past, Altes challenges the nostalgia of benevolent colonialism to reveal its oppressive nature.

Des p’tis gars is just one example of multiple memories of Algeria (other than his own) posed together to form a critique. Altes’ recourse to community images is a way of engaging in postmemory work, as Hirsch explains, “because these family photographs are documents both of memory (the survivor’s) and of what I would like to call post-memory (that of the child of the survivor whose life is dominated by memories of what preceded his/ her birth)” ( “Family Pictures” 8). Altes engaged in dynamic exchange with the memory guardians who still protect the memory of Algeria today. While that generation remains tied to a notion of the past that is “truth” (restorative nostalgia), Altes uses layers to demonstrate both the personal and communal wounds of colonialism. He writes:

my art is definitely not interested in nostalgia with its redolence of the golden age of Arcadia but seeks to appraise the multilayered reality of the French presence in Algeria. It deals with the notion of representations and how these affect the process of memory (as opposed to history) and in turn our identities (mine to begin with).

… I use them [layers] to replace perspective as well as define a sense of time. In my series “a story of revolution(s),” the layering, on top of its obvious technical uses, has similar function especially in terms of accounting for time in terms of history and memory. (Personal communication 24 January 2018).

Conclusion

Though layering over the past could be one way to lay claim to it again, both Guiraud and Altes use layers in ways that call attention to the ruptures and the fragments they have experienced and seen.[10] Both artists are absent of restorative nostalgia (nostos), or an attempted ‘transhistorical reconstruction of the lost home” (Boym xviii). Instead, they recreate versions of Algeria in their works in ways that very directly engage with the algia – the very specific pains evoked in the past both for themselves and for others. Their work is not about reattaching themselves to the homeland but rather about understanding suffering and trauma related to the separation they and their generation experienced. Guiraud physically suffered from this pain and must daily contend with the absence of her arm in addition to the absences of family and homeland. She recognizes, however, that reattachment is not a possible outcome, and she uses her work to connect with a community of terrorism survivors. Taking a broader approach, Altes grapples with the crimes against humanity committed under colonial rule and he fights against attempts to recolonize the past through literature and art. His personal experience is subsumed in the collective but in ways that call that previously oppressively nostalgic memory of colonial Algeria into question. By examining the communal memory, he is able to engage with his own. Both artists encourage “creative dialogue to acknowledge the wounds of the past, the effects of the Algerian revolution” (Altes “A Story” Leverhume), and both Guiraud and Altes explore new ways for France and Algeria to move beyond historical trauma and to understand each other today.

Amy L. Hubbell is lecturer in French at the University or Queensland where she researches Francophone autobiographies of exile and trauma. She is author of Remembering French Algeria: Pieds-Noirs, Identity and Exile (U of Nebraska P, 2015), and A la recherche d’un emploi: Business French in a Communicative Context (Hackett, 2017) and co-editor of several journal volumes as well as The Unspeakable: Representations of Trauma in Francophone Literature and Art (2013), and Textual and Visual Selves: Photography, Film and Comic Art in French Autobiography (2011). She is currently working on her new project, Hoarding Memory: Covering the Wounds of the Algerian War.

References:

[1] These authors and artists inherited the traditions of the “Ecole d’Alger” which peaked in 1935 and included Albert Camus, Emmanuel Roblès and Jules Roy.

[2] After the Algerian government cancelled the second round of elections tipped towards Islamic extremism, many members of the intellectual and artistic communities in Algeria were forced to flee in a new wave of migration to France. French intellectuals working on Algeria during this time were not immune to threat.

[3] Amar Guendouzi in “Contemporary Algerian francophone fiction, trauma, and the ‘war of memories,’” explains that these wars resulted from a long silence on Algeria followed by a series of French memory laws in the 1990s which created “an overflow of remembrance” (236). These memories were complicated by traumatic experiences and the various identity groups and political affiliations of those who remember (236-37).

[4] See Didier Lestrade’s article “Pied-Noir et Pro-arabe” in which he reflects on the ways in which the older generation of nostalgic Pieds-Noirs impeded relationships between France and Algeria. Lestrade writes, “Because of them, Algeria is still suffering; because of them, we open museums that glorify colonialism and we vote for laws that clear their conscience. Because of them, the French political class cannot get past the trauma of independence …It’s a whole chain of blockages that is kept up by the old Pieds-Noirs” (my translation in Remembering French Algeria 1-2).

[5] Zohra Drif left the bomb intended to wound civilians in a coordinated attack for the Armée de Libération Nationale. For more information on how Nicole Guiraud and Danielle Michel-Chich express their experiences with this attack, see my forthcoming article, “Scandalous Memory: Terrorism Testimonial from the Algerian War.”

[6] In personal correspondence, Cuesta stated that the booklet dates back to 1956 or 1957 and was sent to each French deputy in 1998 from the Pieds-Noirs in Nice, but that they were not taken seriously.

[7] Though the victims depicted are the same in both paintings, the cadavers look painted in “Milk-Bar” but resemble photos in “Massacre des Innocents.”

[8] As I stated about Guiraud in “Unspoken Algeria,” “The layering of images of her traumatized body onto nostalgic pieces of her past is evocative of the scar she physically bears today” (309).

[9] The image of the black African in the red chechia was also used on the French “Banania” chocolate drink advertisements which are often criticized as racist.

[10] For an examination of how layering works in contemporary Franco-Algerian art by Zineb Sedira and Katia Kameli, see my article, “Made in Algeria: Mapping layers of colonial memory into contemporary visual art.”

Altes, Patrick. “A Story of Revolutions: Representations, discourses and Identity within the context of postcolonialism and the Algerian revolution.” Leverhume Trust Artist in Residence, University of Portsmouth. Unpublished manuscript.

⎯ . Des p’tis Gars bien d’chez nous. 2013. Digital print on Hahnemuehle paper on Dibond, 140 x 110 cm (55 1/8 x 43 1/4 in.) Janet Rady Fine Art: Focusing on the Middle East. http://janetradyfineart.com/artist/Patrick_Altes/works/891. 13 February 2018. Web.

⎯ . “Re: Art et mémoire.” Received by Amy L. Hubbell. 28 January 2018.

Boym, Svetlana. The Future of Nostalgia. NY: Basic Books, 2001. Print.

Clarke, Stephen. “Maps of a Wretched Past: Patrick Altes.” The Double Negative 19 May 2014. http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/2014/05/maps-of-a-wretched-past-patrick-altes/?utm_source=invitations&utm_campaign=5930f1168c-Biennale_Oran&utm_me%E2%80%A6 Accessed 1 February 2018. Web.

Creative Space CCI. “A Story Of Revolutions, an Exhibition by Patrick Altes.” http://creativespace.cci.port.ac.uk/2014/10/a-story-of-revolutions-an-exhibition-by-patrick-altes/ Accessed 19 February 2018. Web.

Cuesta, Hervé. “Re: informations au sujet des photos des enfants victimes du Milk Bar.” Received by Amy L. Hubbell. 15 July 2016.

Guendouzi, Amar. “Contemporary Algerian francophone fiction, trauma, and the ‘war of memories.’” Journal of Romance Studies 17.2 (Summer 2017): 235-53. Print.

Guiraud, Nicole. Algérie 1962: Journal de l’apocalypse, Tagebuch der Apokalypse. Friedberg, Germany: Atlantis, 2013. Trans. Amy L. Hubbell and Muhib Nabulsi. Algeria 1962: Diary of the Apocalypse. https://www.academia.edu/35269450/Nicole_Guiraud_Diary_of_the_Apocalypse http://editionatlantis.de/publikationen/details/?pub_id=45&lang=en. Web.

⎯ . Interview by author. Masseube and Montpellier, France. 29 June 2012 to 2 July 2012.

⎯ . Survivre. Une exposition du Centre de documentation des Français d’Algérie dans le cadre du Pôle muséal. Catalog. Éd. Marie Costa. Colleccio Font Nova, 2012. Print.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Family Pictures: Maus, Mourning, and Post-Memory.” Discourse 15.2 (1992): 3-29. Print.

Hubbell, Amy L. “Made in Algeria: Mapping layers of colonial memory into contemporary visual art.” French Cultural Studies 29.1 (2018): 8-18. Print.

⎯ . Remembering French Algeria: Pieds-Noirs, Identity, and Exile. Lincoln: U of Nebraska P, 2015. Print.

⎯ . “Scandalous Memory: Terrorism Testimonial from the Algerian War.” Contemporary French and Francophone Studies 22.1 (2018). Forthcoming. Print.

⎯ . “Unspoken Algeria: Transmitting Traumatic Memories of the Algerian War.” The Unspeakable: Representations of Trauma in Francophone Literature and Art. Eds. Névine El Nossery and Amy L. Hubbell Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2013. 305-324. Print.

Lestrade, Didier. “Pied-Noir et pro-Arabe.” Revue Minorités. 20 Feb. 2011. http://minorites.eu/index.php/2-la-revue/999-pied-noir-et-pro-arabe.html

Accessed 1 February 2018. Web. Trans. Amy L. Hubbell in Remembering French Algeria pp. 1-2. Print.

Martini, Lucienne. Racines de papier: Essai sur l’expression littéraire de l’identité Pieds-Noirs. Paris: Publisud, 1997. Print.

Published on March 1, 2018.