Translated from the Italian by Hope Campbell Gustafson.

This is part of our special feature, Beyond Eurafrica: Encounters in a Globalized World.

When I think about Mama before the war, I see her sitting on her heels in the courtyard, hair wrapped in a green net, her face yellow with turmeric and butter, the precious ingredients of her beauty mask. She’s vigorously stoking the fire, fan clutched in her hand, while her head nods almost imperceptibly, right and left, up and down, like the feathery flower heads that sprout from acacia in bloom.

The brazier is a cone of clay secured between her thighs. It emits ash and lapilli, and only settles when the embers are glowing hot, ready for cooking. Then Mama puts the water on to boil, though she doesn’t prepare tea for us as other women do. Instead, she makes a decoction of roots to protect us from typhus and cholera, pneumonia and measles, because there are too many diseases in this world and you can never be too cautious.

Mama is a medicine woman by vocation, which is why the villagers both fear and admire her. My little sister and I wear bracelets of myrrh around our wrists, antidotes against snakes and sorcery. Mama’s features, beneath the subtle mandarin-coloured sheen, are like those of an Egyptian goddess, engaged with secrets which weren’t inherited, because it seems there were no herbalists among our ancestors.

She watches me and smiles graciously while I draw us some water. There isn’t much left; later today I’ll walk to the well and ask the cart-driver if he’ll come fill the water tank. A barrel never lasts more than a week, and transporting it requires the strength of a donkey.

Mama built our house with flamboyant tree branches and braids of palms, mixing a paste of resin, dung and red sand to protect us from water and from the monsoons. At dawn, the walls are streaked with coral iridescence like in a sea cave.

I clean my teeth with a stick of caday, then gently wake my little sister who turns over on our straw mattress and hugs me, half asleep: she’s still young, her curls are damp on the nape of her neck.

Each morning, we rise early and eat a breakfast of milk and sorghum before getting ready for school, carefully pulling on our threadbare uniforms and worn-out sandals. No one would comment upon our beauty if it weren’t for our hair. Mama extracts gelatine from the leaves of the Jujube tree – the only soap or shampoo we’re allowed to use – then sprinkles us with frangipani water and braids multicoloured ribbons into our hair. The wind transforms it into long vines filled with flowers. And thanks to her treatments, our hair has grown in extraordinary ways, black and lustrous like ebony, the fibres as ductile and strong as gold.

In the evenings, we take turns brushing each other’s hair, crouched down in the threshold, coating our hair with coconut oil and separating it into sections that we twist like little tornadoes.

Recently, Mama managed to set up a small kiosk next to our house where people in the area can buy rice, flour, molasses and sesame oil; tomato paste, Omo detergent and fuel; matches, tea leaves and, remarkably, even henna dust. But people mainly stop by to ask about Mama’s healing power and remedies, for which she never accepts monetary compensation.

She says it would be the same as making a pact with the devil, getting rich from others’ misfortune. Her patients still insist on repaying her somehow, so instead they load her up with kilos of sugar, jars of tomato paste and bottles of oil.

Mama prescribes earth-almond flour, melted butter and honey for newlyweds; qurac pods for parasites; aloe extract for swelling; carmo leaves for broken bones. She also prepares a dessert containing acacia resin and goat milk for the holidays. Yet the most sacred tree for her, the one she always takes us to see, in the middle of her temple of medicinal plants, is the Gob, the Jujube. ‘You see this stick,’ she says, ‘its roots grow in the sky, it cures ulcers and wounds, nausea and abscesses. Whoever dies with jujube seeds in their body goes directly to heaven.’ From its flowers, she extracts an infusion for the eyes, and when it’s the season, we go with big baskets to gather its fruits. When we get home, Mama candies them, dries them out and grinds them up so as to always have a reserve for her remedies and cures in the pantry. She sifts through the fruit with her mortar, a necklace of amber yolks around her neck, trusting in the miracle of plants.

Ah, but Mama doesn’t foresee the war around the corner, the fleeing people who seek refuge in our village. The city burns and glows like a brazier, a filthy firework under the full moon. My little sister gets sick with an illness as horrible as the plague and Mama is no longer able to procure her roots, barks, berries. It’s too dangerous to venture out there in the brush. The little one squirms on the wicker mat, being eaten by the fevers, the worms, the sores, her mouth filled with foam. Her beautiful hair falls out in clumps, leaving a mosaic of tiny scabs.

Defeated, Mama calls the cart-driver to carry her child to the hospital and entrusts me to the neighbours’ benevolence, promising to return in a few hours.

Ayan Nur, a minor; country of origin: Somalia. Declares that mother and younger sister reside in the United States and requests that the procedure of family reunification be commenced. [Interpreter’s note]

The world seems encased in ice this morning. I walk with my gaze lowered, like an acrobat on the frozen path. I see only the frayed corners of my duffle coat and the fringe of my scarf wrapped tightly around my shoulders. I’m not used to this cold. I can no longer feel my feet; I must have holes in my shoes. The sky is bent down towards the ground, carrying white clouds heavy with water. I try to feel my way forward, but my hands can’t get a grasp on the fog. It’s still early, I keep waking up at dawn. I pace back and forth, the light the colour of iron. Only in the war did I see such barren landscapes of sad browns and bronzes. The trees have a funereal look. I jam my hands deep inside my pockets and jog on the spot. The fog lifts slightly, and the hour of my appointment finally arrives.

I stop in front of the villa’s wrought-iron fencing and hold my breath. The villa hides itself almost shamefully behind a veil of organza. The entire building would seem deserted were it not for a flicker of light in the second-floor window, so faint it almost looks like the reflection of the sky, if only the sky weren’t covered by a blanket of clouds today. I push open the gate and step onto a path of dead leaves, some the colour of honey, others like embers and earth. Tall trees with leafy tops and tangled webs of thorns surround me. A gust of wind loaded with hail hits me like a handful of uncooked rice. The gate shuts behind me with a mournful sound, isolating me from the outside world. I am enclosed within an autumnal garden. I approach a heavy lead-grey door with large off-white stains. There isn’t a bell but a cast iron door-knocker in the shape of a sphinx. I feel a deep anguish, but I need to be brave, the classified ad in the paper seemed promising.

As I cross the threshold, five crystal chandeliers light up and the door at my back closes silently, just as it had opened. I stand motionless in the centre of a constellation of vases filled with chrysanthemums, waiting for somebody to reveal themselves. There seems not to be another living soul in the villa. I’d almost resolved to leave when a black dog with a silver collar walks up to me. The owners of the house must be rich and eccentric. I’m petrified, there’s nothing I can do about my fear of dogs, in my country we had to defend ourselves against the strays. He wags his tail, licks my wet shoes, his eyes the colour of bananas, his ears dangling. He seems to want to tell me something. I swallow my fear and decide to follow him into a small room with grey walls and a small already-set table in the centre. He sits on his hind legs, as though inviting me to take a seat. There’s a cup of coffee waiting for me, a basket of pomegranates and – on a platter covered with an enormous silver cloche – freshly baked bread with butter and orange marmalade. I hadn’t eaten anything since morning. Before I finish breakfast, the dog disappears. I tiptoe through a labyrinth of vaulted rooms, each one smaller than the last like a set of Chinese boxes. I can hear the faint voice of a child behind a half-open door. Could this be the one mentioned in the ad? I step into the dark room, immediately stunned by a miasma of sour milk. A nauseating stench, sharp like shards of glass. The voice, however, grows stronger, crystalline. My pupils get used to the dark and I clearly distinguish two little phosphorescent eyes, green like apples, green like sea fruits. I find my way in the dark, feeling the walls, in search of a light source. Here, a heavy curtain. I pull it aside slightly, afraid that the child might be bothered by the sudden brightness. Now I can see her entirely; she’s standing at the edge of the crib, bouncing. In one of her hands she has an empty baby bottle, her onesie soaked with regurgitation and urine. And yet the child isn’t crying, she’s holding out her little arms towards me, almost chirping. She must be a little over a year old. I pick her up, automatically setting her on my hip just as I used to with my little sister. I’m no longer afraid, I venture down the hallway in search of a bathroom. The girl absolutely must be changed; the smell is disgusting. I enter a large room with a tub in the middle, set on feline claw feet. The faucet is made of brass. I turn it on to check the water temperature and I free the child from her wet onesie and heavy diaper. She’d worn it for too many hours, it was soaked with a yellowish stain. I wash her gently, I’m afraid of hurting her, she has pink spots all over her stomach and blonde hair like fine silk. Mama would be proud if she saw me now: if I find a good job soon I’ll be able to join her in the United States, her and my little sister. I get a towel to wrap the child in and, upon leaving the bathroom, see the Signora for the first time. She’s wearing an amaranth red silk slip, her shoulders covered by a scattered mass of fire-red hair. I back away, startled. She seems to be made of milk and freckles, two agate gems dangle from her ears. I’ve never seen so much exposed white skin.

‘So, you’ve already met?’ she asks enigmatically, her gaze impassive. I stammer, unsteady, the child tightens her grip on my shoulders, her little snow-white hands on my black skin.

Investigations conducted thus far are not sufficient to track down any direct relative of the client either in Europe or in the US. [Interpreter’s note]

I watch as the cart carrying Mama and my little sister disappears behind the dunes. Mama turns her head back every few minutes, waving frantically until she is out of sight. The horizon is bathed in blood red; black lines sharp as knives radiate from the last slice of sun. It gets dark quickly, the neighbour looks out from the doorway and invites me to join her, but I tell her I can’t leave, I have to watch over the house while Mama is away. She brings me a small plate of meat stew with a bit of rice. I eat alone, outside on the wicker mat, waiting for them to return. To calm my nerves, I grab one of the few jujubes left, they have a musky scent. I hold the pit in my mouth, roll it around with my tongue and then swallow it whole.

The lanterns agitate the shadows of passers-by and I hear quiet voices through the thin walls made of branches and dung. I pick up the hand-shaped comb and undo my braids, my hair is so long it almost touches the ground. The sky fills with white stars and I can see the Southern Cross next to the figure of a camel. Mama often tells us the story of a time when there was a terrible famine in a village in the North and the men decided to kill the camel of the sky and feed on its meat. So, they climbed a tall mountain and, as they still couldn’t reach it, got on one another’s shoulders until they were able to cut off its tail. In pain, the camel fled towards the South and then sat itself down, exactly as I see it now, ashamed of its lacking backside. Its large body comforts me, keeps me company. The camel saved itself from the greediness and cruelty of men and left a luminous wake in its flight, that of the Milky Way.

It’s night when I’m wakened by a metallic noise like that of frenzied cicadas. I look through the cracks in the wall and quickly recoil: nearby houses are on fire. I rush outside and see women ruffled like wild birds, I see adult men falling like ripe fruit, I see the neighbourhood stormed by men meaner than stray dogs, abnormal creatures, with agate-like eyes blacker than the bottom of hell. The air is saturated with sulphur and dirty water; I move past the flames as lightly as a yellow butterfly.

A pack of ferocious dogs is at my heels, my already worn-out clothes have been reduced to rags. Thin streaks of blood line my legs. I arrive at the burial ground of my mother’s temple. The jujube’s burnt trunk is still smoking. I hug it, although certain it won’t be enough to hide me. And suddenly I see a florescent wake envelope me completely. My hair takes the form of the jujube’s spiky branches, it grows abundantly, hanging down towards the ground until covering me completely. My hair sprouts jagged and luminescent leaves and little white flowers in the shape of stars. The dogs howl around the base of the jujube, but they can no longer see me.

Numerous are the omissions and incongruences of the events described in the course of the hearing for a request for asylum. The client exhibits signs of torture and abuse. [Interpreter’s note]

It’s spring. The child and I follow the Signora through the garden encircling the villa. She removes dead leaves with a rake and piles them up on the side. She carefully clears the area at the foot of the willow tree. I tell her that the branches of the tree hang down like those of the jujube and I almost feel tempted to tell her about my metamorphosis. She nods sympathetically: I don’t know the jujube tree, she replies, but you are quite right about the willow, that’s why here we say it’s weeping. Her face is motionless in the shade of a wide-brimmed hat. The child toddles unsteadily, attaching herself to my skirt; with her little hands, she picks dry hydrangea flowers, sits down in the grass and reduces them to dust. We help the Signora plant hyacinth bulbs around the cypresses. Clusters of wisteria with its intense aroma dangle from the fence. The Signora sings with an almost deranged joy about the first blooms. The child has her same milk-white skin tone; I protect her with a thick layer of sunscreen and follow her with a little umbrella: by now her curls go far past her shoulders. The Signora knows of my passion for hair, and yet she doesn’t understand why I comb it with such care, why I coat it with regenerative creams, why I protect it from the wind and sun. The Signora’s hair blazes like a flow of lava. She walks, dirtying her clothes with the rich soil and the orange pollen from the lilies. I wonder if her garden has a corner for medicinal plants too, and she responds coldly that she has no real reason to garden, no purpose other than beauty.

When it’s time for a snack we go back inside, the child and I play with wooden blocks on a sand-coloured Persian rug. The Signora brings a silver platter, two cups of jasmine tea and a box of butter cookies. I take a container of fruit yoghurt out of the fridge for the child. While I feed her, she sticks her longest locks into her mouth, getting them all sticky. The Signora sips her tea and invites me to sip mine as well. Then, calmly, very calmly, she announces that soon she and the child will be leaving on a long trip to the United States that she can no longer delay. She knows that I dream of joining my mother and my little sister there, but, despite all her attempts, it’s impossible for her to bring me with them; the laws don’t allow it. But I can stay in her house if I like: the time will fly, it’ll feel as though only a few minutes have passed by the time they’re back.

Then she goes to the child, gathers her hair in her hands and adds, in her icy voice, that she’ll have to cut it before leaving, because she won’t know how to brush it in my absence. I stay silent, I leave my tea untouched. The Signora retires to her quarters. I decide I won’t allow her to leave with the child, I won’t allow her to cut her hair either. I’ll wait for the Signora to fall asleep and escape out the gate with the child in my arms. I don’t want them to disappear behind the hills, just like my Mama and little sister behind the dunes; I don’t want to lose them to America too.

There is a reasonable amount of evidence to conclude that the mother and sister of the client had lost their lives during the massacre in the village of origin. [Interpreter’s note]

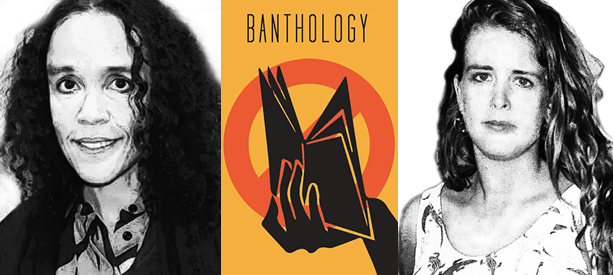

Ubah Cristina Ali Farah is a writer, poet, playwright, and performer of Somali and Italian descent. She was raised in Mogadishu, Somalia, but fled in 1991 at the outbreak of civil war, and eventually settled in Rome to teach Somali language and culture at Roma Tre University. Her stories and poems have appeared in several anthologies and her 2007 novel Madre piccola was awarded the prestigious Vittorini Prize. In 2006, she was awarded the Lingua Madre National Literary Prize.

Hope Campbell Gustafson is from Minneapolis. She double-majored in Italian Studies and English at Wesleyan University before moving to Italy. During the past four years she has interned at Civitella Ranieri Foundation (an artist residency program) in Umbria, taught English at Collegio San Carlo in Milan, and worked as Student Life Coordinator at Temple University Rome. She has done various kinds of translation work, with an emphasis on contemporary Italian prose.

This story from Banthology is published by permission of Deep Vellum Publishing and Comma Press. Copyright © remains with the authors 2017. This collection copyright © Comma Press 2017. All rights reserved.

Published on March 1, 2018.