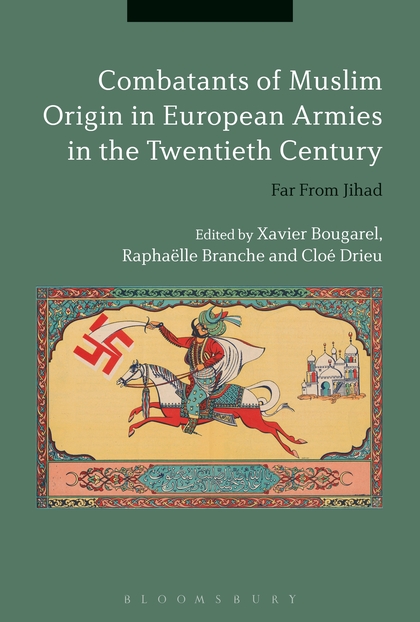

Combatants of Muslim Origin in European Armies in the Twentieth Century: Far From Jihad, ed. Xavier Bougarel, Raphaëlle Branche and Cloé Drieu

This is part of our special feature, Beyond Eurafrica: Encounters in a Globalized World.

The service of peoples of non-European descent in twentieth-century European armies has drawn increasing attention from scholars in recent decades. Historians such as Tyler Stovall have examined the experiences of colonial workers and soldiers in France during World War I, while Richard Fogarty has studied the French army’s reliance on troops recruited from its colonies during the same war. A certain number of works on related topics has even been produced for non-scholarly audiences, including Days of Glory, a 2006 film about African troops who fought in Europe during World War II, and Enemy of the Reich, a PBS documentary about a Muslim woman who served as a spy for the British in Nazi-occupied Paris.

This edited volume builds upon the important but limited scholarship on the diversity of the armies that waged war within Europe during the twentieth century. Focusing in particular on troops who identified as Muslims and fought in European armies, it seeks not only to narrate the experiences of various Muslim groups within European forces, but also to examine the religious, political, social, and cultural significance of their service. Most of the Muslim soldiers who are the subject of this book were of non-European origin, but some essays, such as Xavier Bougarel’s study of Bosnian Muslims recruited to fight for Nazi Germany, focus on Muslim Europeans.

As the subtitle Far from Jihad suggests, the book is framed, in part, by the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V’s decision in November 1914 to call Muslims across the world to jihad in support of the Ottoman Empire and its allies against enemy European states. Many of the essays in this book that deal with World War I assess the extent to which various Muslim groups answered this call; they find that few did. Implicit within this analysis is a concern for understanding how calls to jihad impact the Muslim world today, as well as examining the extent to which Muslims of diverse races and religious doctrines identify themselves as part of a universal Muslim community. On the latter point, too, the contributors to this volume mostly conclude that ethnic and regional identities were more important to most Muslim troops in Europe than was any notion of Pan-Islamism.

While the book’s nominal chronology spans the twentieth century, its scope is primarily limited to the first and second world wars. This focus is understandable; as the editors note in the introduction, some two million Muslims served in Europe during the First World War, followed by several hundred thousand during World War II. Outside of these two conflicts, the service by Muslims in European armies during the twentieth century was much more limited. Nonetheless, some of the essays, such as Tanja Bührer’s chapter on Muslims in the colonial army that defended German East Africa, touch on the service of Muslims in European colonial forces in the decades that preceded the First World War, and Claire Miot explores how European perceptions of Muslims in European armies impacted state policies during the decolonization period that followed World War II. There is no mention of Muslims in European armies prior to the later nineteenth century, even though Muslims fought in parts of Eastern Europe in significant numbers during the early modern period, and existed sporadically within regiments in western Europe as well.

The essays in the volume offer valuable and sometimes fascinating information on the experiences of Muslim troops within diverse regions of Europe during the wars of the twentieth century. Essays by Salavat M. Iskhakov and Kiril Feferman study Muslims, mostly from Russian or Soviet territories in central Asia, who served in Russian or Soviet armies during the world wars. Julie le Gac’s fascinating essay analyzes efforts by French and British psychiatrists to treat combat-related disorders among Muslim troops during World War II, and the ways in which European perceptions of the Muslim psyche informed such endeavors. Gilbert Meynier writes about Muslim Algerians who fought for France during World War I, and considers how their experiences helped to fuel patriotic sentiments that eventually led to Algeria’s independence from France several decades later. Daniel Owen Spence’s essay, about Muslim sailors on British ships during World War II, shows that Muslim military service extended to European navies.

In general, the findings of the essays in this volume are unsurprising. For the most part, the authors conclude that, while being a Muslim in a European army (or navy) was difficult and often entailed confronting discrimination or prejudice, religious practice did not usually interfere with military service in a serious way. Most European officers and publics viewed Muslim troops through a lens that mixed exoticism with hesitation and gratitude. In cases where Muslims remained within European states following demobilization – as did, for example, Muslims from Central Asia who became citizens of the Soviet Union – military service helped to integrate them into European societies. These are the sorts of trends that one would expect, and they align with the findings of earlier studies of Muslims and non-Europeans in twentieth-century European armies.

That said, these essays explore the experiences of Muslims in European armies from several novel perspectives. Although the feasibility of studying Muslim troops’ self-perceptions is limited by the scarcity of source material, these essays offer important insight into the ways in which military service in Europe impacted Muslims, and the extent to which Muslims should be treated as a homogeneous group within the historical contexts in question. They also explore the relationship between race and religion in constructing European understandings of Muslim troops and in the formulation of political identities among people who considered themselves Muslim. For each of these reasons, this is an important volume that will interest scholars of race, religion and identity in any context within modern Europe.

Reviewed by Christopher Tozzi

Combatants of Muslim Origin in European Armies in the Twentieth Century: Far From Jihad

by Xavier Bougarel, Raphaëlle Branche, and Cloé Drieu

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Hardcover / 256 pages / 2017

ISBN: 9781474249430

To read more book reviews, click here.

Published on March 1, 2018.