This is part of our special feature, Beyond Eurafrica: Encounters in a Globalized World.

Africans in Europe

The history of the entangled relationship between Africa and Europe has been shaped by a remarkable mobility of people, capitals, ideas, and goods that traveled across the two continents—pushed and pulled by colonial powers, trade of human and material resources and labor forces, missionary activities, and adventurous travels of people from both sides of the Mediterranean. In the twenty-first century, more than ever, Africans and Europeans are meeting and living together not only in Africa but also in European cities and societies. According to recent data, in 2016, the majority of new European citizens were from Africa.[1] In countries like Italy, Africans make up 20 percent of the migrant population (or 1, 047, 229). The majority of them come from north Africa (13 percent), followed by sub-Saharan Africa, specifically 2 percent from Senegal, 1.75 percent from Nigeria, and 1 percent from Ghana.[2]

Among the migrants coming from Nigeria and Ghana, the vast majority are Pentecostals. Their experience as blacks, economic migrants, and non-Catholics in a predominantly white and Catholic society reveals some of the core features of the twenty-first century relationship between Africans and Europeans in European cities and societies. That they are Pentecostals makes them a particularly complicated Christian “other” that challenges the social and religious order of the Italian society defined by the Roman Catholic ethnoreligious power.

African Pentecostals in Italy

The history of today’s African Pentecostal churches in Italy dates back to the end of the 1980s and the early 1990s, when the first significant migratory movement from West Africa reached Italy. In those year, Nigerian and Ghanaian migrants’ departure cities, like Lagos, Benin City, as well Accra’ and Kumasi, witnessed an impressive growth of Pentecostal megachurches and prayer camps[3] that were attracting members from the historical Protestant and Catholic churches.

The 1980s were also the years of a strong demand for labor in the farming sector in Southern Italy and from the industries and factories in the north of the country. Yet, since the 1980s, the exodus of manufacturers from Italy in search of lower-cost options in Eastern Europe or southeast and central Asia has caused increasing unemployment and worsening working and living conditions. A tedious national economic crisis fed collective social and economic insecurity, while media and the growing xenophobic parties contributed strongly to generate and shape a collective imaginary of migrant’s inescapable illegality and criminality. As a result, African women and men started to experience growing criminalization, expanding incarceration, and escalating racial violence, as we see in the cases of Florence in 2011 and Macerata in 2018, in which fascists and right-wing militants claiming to defend the Italian nation from the invasion of unwanted, dangerous, and indeed criminal migrants, brutally attacked and killed African migrants.

African women and men are responding to these dramatic social crises and instances of racial violence. They are mobilizing the resources of the long-established African diasporas, joining local civil rights associations and organizations, and fiercely expressing their anger at the racial violence and the economic and social injustice they experience. Indeed, Africans in Italy are using the resources available to them to critique and resist the social and racial order of Italian society.

In particular, African Pentecostal churches are playing a singular role in the African communities in Italy. Like other Pentecostal churches in Europe, they support their newly arrived members’ search for housing, jobs, and residency permits. Some of the churches and their pastors are at the forefront of helping young men and women caught up in human trafficking and, even with limited resources, they provide temporary hospitality, at times economic support, and certainly a home away from home where people of the same ethnic group can share their common journey, memory of home, and religious practices.[4] In these churches, African women and men create a safe space far from the inquisitive and suspicious gaze that they experience in their everyday lives.

But these churches also have another important role among the Nigerian and Ghanaian communities: they provide them with a crucial yet unconventional political space to voice their intimate social critique and collective dissent of their imposed social sufferings and marginal position experienced both in Italian society and more specifically in the Italian religious field. For these Africans, marginality is not only defined by their migrant condition but by their Pentecostalism: they are not Catholic in a society where Roman Catholicism is a religious and social power.

The Enduring Catholic Hegemony

The power and influence of Roman Catholicism is not new to African Pentecostals. In Africa, Catholicism is a massive demographic, infrastructural, and socio-political power. But there it has strong and powerful competitors, including Protestant and Pentecostal churches, Islam, and traditional religions. In Italy, Catholicism doesn’t have significant competitors, other than the Italians’ disaffection for the Catholic Church as religious institution. Yet this disaffection is not significantly affecting the Catholic church’s influence on Italians’ lives. Despite the increasing number of people disappointed with Catholic institutions, and despite the growing presence of the religions of the migrants, the number of Italians converting to other faiths or participating in the activities of these new religious communities is negligible.[5] In fact, although other religions are offering alternative ways of being religious, Italians remain essentially faithful to their Catholic predispositions, which do not necessarily involve going to church on Sunday or receiving the sacraments. Indeed, recent research has shown that the Italian lifestyle has changed, and with it, religious practices. The number of people attending official Catholic rituals, like Sunday Mass, and taking holy sacraments (Baptism, communion, confession, confirmation, and last rites) is declining and Catholic parishes are increasingly losing parishioners.

Nevertheless, the Catholic Church remains the expression of a modern ethnonational Italian identity, the custodian of individual and collective memory as well as a religious and social world view.[6] As Valentina Napolitano argues in her work, in Catholic-dominated societies, Catholicism is both an individual experience, a religious organization, and a social institution; it is a “passionate machine” that operates at the intersection of governmentality and production of passions and constantly recalibrates its sovereignty over material and immaterial territories.[7] It is this sovereignty that defines the “otherness” of other religious expressions as well as their access to material and social resources.

Despite the historical and social changes that have undeniably shaped contemporary Italian society, Catholicism still retains several features of the hegemonic power observed by Antonio Gramsci in his post-war analysis. The Gramscian Catholic hegemony is not a dominion, but a highly persuasive and taken-for-granted horizon of a political and cultural project that includes a conception of the world and of the sacred.[8] This horizon legitimates Catholic sovereignty over the sacred, governed through a specific and persuasive aesthetic regime. This regime includes articulated religious rituals, artful combinations of regalia and gestures, as well as a stunning visual and material culture. These religious aesthetics shape religious practices, but they also sustain collective identities and subjectivities.[9]

Catho-Pentecostal Aesthetics

In Italy, African Pentecostals find themselves immersed in the Catholic aesthetic regime visible not only in the majestic cathedrals, stunning sacred art, and public religious rituals but also in the deeply entangled relationship between church and state, a relationship that extends to the pompous ceremonies of both local authorities and church hierarchies. Catholic religious aesthetics in Italy are indeed overwhelming and deeply ingrained in Italian social life. Pentecostals observe the spectacle of Catholic aesthetics and power and often shake their heads and react in disgust, for example at the remains of human bodies that Catholics venerate as relics.

Yet, these Pentecostals are a religious minority that occupies a very marginal place in the Italian socio-religious and political arena. As in other European countries, Pentecostal churches are officially acknowledged only as cultural associations. Besides, their religious practices, especially when related to healing and deliverance, often generate suspicion and recall to the colonial imagination the exotic dark power of black magic, voodoo, and superstitions.[10]

But even in the face of such suspicion and marginality, African Pentecostal churches have found their own particular way to express their spiritual and political subjectivity and to mirror to Roman Catholics their suspicion of the authenticity of the Italians’ Roman Catholic religious practices, which appear to the Africans as very similar to the traditional religions they left behind in Africa.[11]

Intriguingly, although African Pentecostals reject Roman Catholicism as a religion and as the ethnoreligious principle that governs the Italian nation state, they nonetheless appropriate and manipulate Roman Catholic aesthetic power for their own spiritual ends. In other words, they use what sustains Roman Catholic religious power and Italian ethnoreligious identity to express their religious and social dissent. How so?

In African Pentecostal churches in Italy, one can observe what I call a surprising transcultural “Catho-Pentecostal” visual and material culture. For instance, one can see African Pentecostals wearing religious robes that seem strikingly similar to Catholics’ vestments. Such cases are particularly noticeable when female pastors use Catholic-style robes, as in the case of an iconic female Ghanaian Bishop named Diana. She claims to be the first female African ordained as a bishop in Europe. She is particularly known in Italy for her work with young Nigerian and Ghanaian girls and for campaigning tirelessly for the ordination of female pastors and bishops, ordination that, she says, will encourage women to take the right path and bring honor and dignity to African women in Italy. After her own ordination in Ghana, Bishop Diana started ordaining women, and greatly increased the number of women pastors in Italy. Her very presence and appearance as black female religious leader, often dressed in Catholic robes, in a Catholic country where women have no access to priesthood, is an intriguing religious and social statement conveyed with an aesthetic break, such as the suspension of the Catholic aesthetic sovereignty over the rules and aesthetics of religious authority.

Her style is not mere provocation but the aesthetic form of her political imagination.Bishop Diana dresses like a Catholic cardinal: she wears a black robe with a red cincture, and high-heeled red stiletto shoes. Adorned in her regalia, she proudly walks down the street, in her black-and-red robe looking like an otherworldly apparition: a black female Catholic cardinal walking down an Italian street.[12]

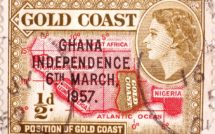

The “Catho-Pentecostal” aesthetics also include altar decorations with images of Jesus, like the Transfiguration of Christ of Raffaello Sarti, that was once an altarpiece at the church San Pietro in Montorio in Rome:

It is interesting to note that in Italy there are only two altars decorated with a copy of Raffaello’s Transfiguration: one of them is an altar in the Basilica of Saint Peter at the Vatican, and the other is in the headquarters of the first Ghanaian Pentecostal church in Italy (see image).

Other Pentecostal religious practices also emerge at the intersection of Roman Catholic and Pentecostal aesthetics. Examples are rituals of consecration using oil, wafers for the healing communion, and holy water. Yet what one might think could connect Catholics and Pentecostals actually only pushes them further apart and increasingly excludes them.

African Pentecostals as a New Type of European Subaltern

In Italy, Pentecostals experience multilayered forms of exclusion and have limited access to the public arena to forcefully voice their dissent of the social and religious order of Italian society. In Italy, Pentecostals are not even recognized as legitimate religious authorities and so it seems particularly unlikely that they could subvert the Catholic aesthetic order. And yet they are creatively disturbing that order through appropriations, manipulations, and remediations that irrupt in the Italian social and religious arena as political and spiritual events, such as the rare and exceptional moments when the excluded subjects suddenly become visible and with their doing and being break the dominant order of things.[13] These events open a space to rethink reality from the standpoint of the excluded, in this case, African Pentecostal migrants in Catholic society.

Pentecostals do not deliberately or consciously intend to overthrow Catholic authority over the sacred, yet neither are their transcultural “Catho-Pentecostal” aesthetics mere gestures or aesthetics of disobedience or provocation. Their dissent doesn’t take place in the realms of government, party politics, or the conventional arenas of political debates. Neither is their opposition consciously articulated or explicitly declared. However, the fact that their dissent is not open and addressed directly to the Italian religious authorities doesn’t make it any less relevant. As Jean Comaroff has argued in her work on the conscious and unconscious religious practices of the Thsidi churches in South Africa, there are various conducts concerned with power that should not be dismissed as apolitical only because they are not in explicit opposition.[1]

African Pentecostals’ transcultural religious aesthetics might appear to be acritical and at times paradoxical, but they have the intrinsic and coherent political and ethical aim to envision another religious order whereby other religious authorities, specifically African migrants, have an equal share in the mediation of sacred power. By doing so, African Pentecostals use their catho-pentecostal aesthetics as political devices that momentarily turn their caged marginalization into liberation. For some skeptics, Pentecostal aesthetics and their embodied religious worlds might look like emblematic examples of futile happiness, a distraction, or at worst a narcotic that keeps Africans away from the real battleground of struggle for economic and racial justice, dignity, and freedom of movement. Yet, an attentive examination of their transcultural religious practices and aesthetics challenges the rigidity of concepts and ideas about what politics is and shows how the political might also take place in nonconventional political arenas and beyond consciously political action.

The politics of the religious aesthetics of African Pentecostals in Italy are not new. Several years ago, Antonio Gramsci also observed similar practices in the religious cultures of Southern Italians, often referred to as folk Catholicism. According to Gramsci, Italian peasants’ modification and distortion of official Catholic prayers, liturgies, and sacramental objects were subtle insurrections meant to escape the hegemonic power of official Catholicism and the strict control of the Catholic hierarchies over religious and socio-political practices. Indeed, the peasants’ struggle was a subterranean, not fully conscious form of dissent that was disturbing the hegemonic official order of the sacred governed by official Catholicism.[1] One can recognize a similar struggle in the subtle practices of appropriation and manipulation that generate African Pentecostals’ aesthetics of dissent. From similar and marginal social positions in Italian society, both folk Catholicism and African Pentecostalism challenge the hegemonic power of Roman Catholicism.

The parallel between the Italian subalterns and African Pentecostal migrants in contemporary Italy doesn’t intend to suggest that the relations of power and oppression experienced are in any way equivalent. And certainly the paramount place of Catholicism in Italy has changed in the meantime. Yet, the Catholic Church still retains some of the features of the hegemonic power that Gramsci examined in his post-war analysis of Italy. Also, African Pentecostals suffer different social conditions shaped by the specific economic regime of late capitalism that involves a highly exploited labor force coming from the global south and a long and deplorable history of racial discrimination and violence. It is nonetheless intriguing to observe how African migrants are becoming part of a long history of anti-hegemonic struggle against dominant social and ethno-religious orders. Although the shaping of the African religious and social subaltern is occurring in a different historical time and social setting, Pentecostal churches are likewise shaping a political project of dissent that includes aesthetic strategies that strongly resonate with the struggles of those that are cast in the part that has no part— the others or the “floating subjects” that demand their authority and power of sacred and social order.

Certainly, African Pentecostals are not the only religious community that is making such a claim in Italy. Other religious minorities, including Italian Pentecostals, are still navigating their complex relations of power with the Catholic Church, along with other Protestant and Christian churches and other religions such as Islam, Hinduism, and Sikhism.

Yet African Pentecostals make their claim from the peculiar position assigned to them in the racial and religious order of Italian society. Their politics of dissent are born from their racialized positions, their imposed marginality, and their supposed second-class Christianity that is often forced into western imaginaries of exotic voodoo rituals and black magic. It is from such a position that they articulate their spiritual and political practices of dissent that arise from their transcultural and Catho-Pentecostal religious aesthetics.

Annalisa Butticci is currently Assistant Professor of Social Anthropology at Utrecht University in the Netherlands. Her areas of research include religious practices and aesthetics, material and visual culture of religions, religions and societies of West Africa, African Diasporas, interreligious and interracial relations, Roman Catholicism and Pentecostalism(s), visual and multimedia studies, and oral history and life stories. She has conducted extensive research in Italy, Nigeria, Ghana, and the US. Her latest book African Pentecostals in Catholic Europe: The Politics of Presence in the Twenty-First Century (Harvard University Press, 2016) was awarded honorable mention by the 2017 Clifford Geertz Prize committee in recognition of its contribution to the anthropological study of religion. She is the co-director of the film/documentary “Enlarging the Kingdom. African Pentecostalism in Italy” (28min), editor of the photographic catalogue “Na God. Aesthetics of African Charismatic Power” (2013), curator of several photographic and multimedia exhibitions, and author of articles published in scientific journals and edited volumes. She received her MA in Political Science from the University of Padua, a post master degree in Gender Studies from the University of Bologna, and a PhD from the Catholic University of Milan, Italy.

Photo: African Pentecostal Church, Italy. Photo Andrew Esiebo

References:

[1] According to Eurostat 2016 the majority of new EU citizens are from Africa (31 percent), followed by North and South America (14 percent), Asia (21 percent), and non-EU Europe (20 percent).

[2] See Istat, 2017.

[3] For a general overview of the transnational history of Nigerian and Ghanaian Pentecostalism, see Adedamola Osinulo, “A Transnational History of Pentecostalism in West Africa,” History Compass 15 no. 6 (2017). For a general introduction on African Pentecostalism, see Ogbu Kalu, African Pentecostalism: An Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[4] Afe Adogame, The African Christian Diaspora: New Currents and Emerging Trends in World Christianity (London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013); Gerrie ter Haar, “African Christians in the Netherlands,” in Strangers and Sojourners: Religious Communities in the Diaspora (Leuven, Belgium: Peeters, 1998), 153–72; Rijk van Dijk, “From Camp to Encompassment: Discourses of Transubjectivity in the Ghanaian Pentecostal Diaspora,” Journal of Religion in Africa 27, no. 2 (1997): 135–159; Abel Ugba, Shades of Belonging: African Pentecostals in Twenty-First Century Ireland (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2009).

[5] Enzo Pace, “Achilles and the Tortoise: A Society Monopolized by Catholicism Faced with an Unexpected Religious Pluralism,” Social Compass 60, no. 3 (2013): 315–331.

[6] Franco Garelli, Catholicism in Italy in the Age of Pluralism (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2010); Franco Garelli, Religion Italian Style: Continuities and Changes in a Catholic Country (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2014); Enzo Pace and Marco Marzano, “Introduction: The Many Faces of Italian Catholicism in the 21st Century,” Social Compass 60, no. 3 (2013): 299–301.

[7] Valentina Napolitino, Migrant Hearts and The Atlantic Return: Transnationalism and the Roman Catholic Church (New York: Fordham University Press, 2016).

[8] There is a rich and nuanced body of works on Gramsci’s hegemony. See, among others, Jean Comaroff and John Comaroff, Of Revelation and Revolution. Vol. 1, Christianity, Colonialism, and Consciousness in South Africa (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991), 23; Bruce Grelle, Antonio Gramsci and the Question of Religion: Ideology, Ethics, and Hegemony (London, UK: Routledge, 2016); Chantal Mouffe, Gramsci and Marxist Theory (London, UK: Routledge, 2014).

[9] On the concept of aesthetics, see Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London, UK: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006); Birgit Meyer, ed., Aesthetic Formations: Media, Religion, and the Senses (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009); Birgit Meyer, “Aesthetics of Persuasion: Global Christianity and Pentecostalism’s Sensational Forms,” South Atlantic Quarterly 109, no. 4 (2010): 741–763.

[10] See Annalisa Butticci, African Pentecostals in Catholic Europe. The Politics of Presence in the Twenty-First Century, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2016.

[11] On the Catholic and Pentecostal reciprocal accusation of idolatry, see the documentary “Enlarging the Kingdom: African Pentecostals in Italy.” Available on ine at www.pentecostalaesthetics.net

[12] The interview with Bishop Diana is part of the documentary “Enlarging the Kingdom: African Pentecostals in Italy” while other pictures of her can be found in Annalisa Butticci, ed., Na God: Aesthetics of African Charismatic Power (Padua, Italy: Grafiche Turato Edizioni, 2013).

[13] Alain Badiou, Being and Event (New York:Continuum, 2005)

Published on March 1, 2018.