This is part of our special feature, Beyond Eurafrica: Encounters in a Globalized World.

Two regions are of relevance when discussing the presence of Dutch in Africa from a historical perspective, i.e. South Africa, which also politically included Namibia between 1915 and 1990, and the Belgian Congo, now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The former witnessed the stable presence of Dutch, and its gradual developed into Afrikaans, from at least 1652 onwards. South-African lawmakers did not officially declare Afrikaans to be a language separate from Dutch until 1983. In the Belgian Congo, Dutch was part of the linguistic landscape from 1879 onwards, namely through the Belgian nationals of Flemish origins living and working in the colony.[1] In what follows, I give a thumbnail sketch of these two histories, and also briefly illustrate when and how they intersected and influenced one another.

South Africa

Dutch has been present in South Africa since the establishment in 1652 of the first permanent Dutch settlement around what is now Cape Town. In the decades and centuries that followed, the Dutch spoken there, detached from its ancestor in Europe, underwent internal developments as well as influences from other languages (such as Khoisan languages, South-African Malay, Portuguese-based Creole, and others) that all took it on a distinct linguistic-historical path.[2] Yet, one should keep in mind that the exact point in history at which a language can be said to have become a distinct or new entity as compared to its ancestor is not only a function of observable grammatical and lexical features, but also, and probably more, a matter of when it is “declared” a distinct one by socio-politically authoritative voices in the speech community. In this respect, it is significant that until the mid-eighteenth century (during 100 years), the newly developing language remained referred to as “Dutch,” at times accompanied by adjectives suggestive of its perceived deficiency, such as “broken Dutch” and “kitchen Dutch.” In the mid-eighteenth century, these qualifications were gradually replaced by ones rather indexing the geographical dislocation from Europe, such as Kaaps Hollandsch “Cape Dutch” (Deumert 2004:65), and later Afrikaans Hollandsch “African Dutch”. Only after the 1870s was the latter shortened to its adjective “Afrikaans,” the name by which the language is known until today (van Rensburg 2015:338).

Also, during more than two hundred years after 1652, Dutch remained the official language—used in written communication, jurisdiction, the administration, the Reformed Church (including for the Bible), and for most creative literature, while the emerging language was only used for informal communication types, and written only occasionally (i.a., Ponelis 2005). By the end of the nineteenth century, a group of Afrikaners felt that the linguistic difference between this “Cape Dutch” (or whichever label by which it was known) and European Dutch had become too large (a view not shared by all) and that too many Afrikaners, due to their typically low schooling, were insufficiently proficient in Dutch (Ponelis 1993:69ff). They formed, in 1875, the “Society of Real Afrikaners” demanding that “Afrikaans Dutch” be considered a language in its own right, and not merely a variety or dialect of Dutch, and be promoted to replace Dutch as the official language (Kannemeyer 1974). The Society largely failed in its ambitions, but its arguments were picked up again in the first decades of the twentieth century, that is, after the second Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902) and the establishment of the Union of South Africa in 1910. The “Act” of 1909 that brought this Union legally into being stipulated that “both the English and Dutch languages shall be official languages of the Union.”[3] No mention of “Afrikaans” as a language, or even a language variety or dialect of Dutch, was made. Around this time, some Afrikaners revived the Society’s claims and arguments of 35 years earlier, stating that Dutch had become a “dead language”’ for many Afrikaners (Steyn 1996:18). Also, in 1914 the Nasionale Party (du Plessis 1986:72), an Afrikaner nationalist organization opposing British linguistic and cultural domination, was founded. The NP almost from the start used Afrikaans as its working language, not Dutch, a practice it officialized in 1917 (du Plessis 1986:72-76). In these years, Afrikaans was also made medium of instruction for Afrikaner children in the Cape, the Transvaal Republic, and the Orange Free State (du Plessis 1986:72; Steyn 1996:21). In addition to this, in 1915 South West Africa (now, Namibia) was annexed after a victory over the German colonizers, and in 1916 the Reformed Church overcame its long-standing hesitation towards a translation of the Bible into Afrikaans, a language it for centuries had deemed “improper” for rendering the word of God (du Plessis 1986:76; Steyn 2009, 2014:175).

All these developments and sentiments led to the “Official Languages of the Union Act” of 1925. It offered an important retrospective reinterpretation of the Union of South Africa Act of 1909: “the word ‘Dutch’ in section one hundred and thirty-seven of the South Africa Act, 1909, and wheresoever else that word occurs in the said Act, is hereby declared to include Afrikaans.”

For the first time in the history of South Africa, an important law text mentioned “Afrikaans” by name. At the same time, it still presented it as an integral part of Dutch, that is, a dialect or variety of it.

After this, the constitution of 1961 marked a next important step in the gradual official, i.e. “declared,” detachment of Afrikaans from Dutch. This text repeated the status of English as official language but for the first time mentioned Afrikaans, not Dutch, at its side. Section 108 stated: “English and Afrikaans shall be the official languages of the Republic, and shall be treated on a footing of equality”. A legal definition (section 119) was added stating: “‘Afrikaans’ includes Dutch.” Thus, it was still deemed necessary to mention Dutch when bringing up Afrikaans, but remarkably the relation of inclusion was now reversed, Afrikaans being presented as the hypernym containing Dutch.

When, in 1983, a new South African constitution was drawn up, section 108 from the 1961 constitution was copied verbatim (becoming section 89), but at this stage, it was finally considered not desirable or necessary anymore to make any reference to Dutch. The definitional statement was not simply omitted from section 119, it was explicitly mentioned not to be in force any longer: “amendment of section 119 by the deletion of the words ‘Afrikaans includes Dutch.’ ”

By the explicit deletion of this phrase, in 1983 Dutch “officially” disappeared from South Africa.

The Belgian Congo

In 1879, the Belgian King Leopold II took the journalist-explorer Henry M. Stanley into his service in order to establish posts along the Congo river and its tributaries, so as to form what would become, in 1885, his private Congo Free State (Cornelis 1991), which in its turn became the Belgian Congo in 1908.

From the start, Stanley worked with officers and agents of a variety of nationalities, many of them Belgians. These Belgian nationals were of either Dutch-speaking or French-speaking origin. As at that time French was still the only language for all formal communication in Belgium, the Belgian officers and agents in the Congo quite naturally used French as the official language among them and for writing. But in private, informal situations, Flemings would naturally return to speaking Dutch (or Belgian varieties of it), especially when all participants in the conversation knew the language. The same communication pattern applied to Belgian missionaries, the first of whom arrived in the 1880s (missionaries of other nationalities had preceded them), and the majority of whom in fact were and always remained Flemish.[4] In sum, the arrival of Flemings in the Congo in the late 1870 and 1880s, marked the beginning of a structural presence of Dutch in Central Africa, albeit always under the hegemony of French as official language.

In 1906, the international condemnation of the massive human rights abuses committed in Leopold’s Congo Free State had reached critical mass. Belgian parliament established a commission to organize the state’s takeover of the Congo from Leopold’s hands, and, between April and September 1908, discussed the commission’s suggestions in plenary sessions (Senelle & Clément 2009). These debates also revolved around the textual details of what would become the “Colonial Charter,” the constitution-like text stipulating the fundamental rights and obligations along which the colony was to be organized (Meeuwis 2015b). One of the topics of these debates was the official status of languages. A number of Flemish parliament members suggested that “the annexation,” as it was commonly called, was a perfect occasion to turn the tables on the exclusivity of French as the colony’s only official language. In the period between the 1870s and 1908, the Flemish in Belgium had made significant progress in obtaining language rights, with laws safeguarding the right to use Dutch in the administration and in schools, reaching a culmination point in the “linguistic equality law” of 1898. This law stated that all laws and decrees were to be promulgated in French and Dutch and that both language versions had equal force of law. In the annexation debates of 1908, some Flemish members of parliament wished to extend all these metropolitan attainments to the new colony by enacting them in the Colonial Charter. They succeeded in having the following stipulations included:

The use of the languages is free. It will be regulated by means of decrees so as to guarantee the rights of the Belgians and the Congolese, and only for acts of the public authorities and for judicial affairs. In these matters, the Belgians in the Congo will enjoy guarantees similar to those that are ensured to them in Belgium. Decrees to that effect will be promulgated no later than five years after the declaration of the present law. All decrees and regulations of a general nature are written and published in the French language and in the Flemish language. Both texts are official. [5]

The last two sentences were clearly inspired by the Belgian equality law of 1898. The first sentence was copied from the Belgian constitution, whose first authors in 1831 had decided to include it in reaction to the language policies of the Dutch King William I before Belgian independence, perceived as restraining linguistic freedom in private contexts (Wils 1977, 1985; Van der Sijs 2004). The limiting phrase “only…” in the second sentence has the same origins.

The commitment, in the last but two sentence, that decrees protecting the linguistic rights of whites (in practice, Flemings) in the Congo would be issued “no later than five years,” in 1913, would be the ground for the fiercest Flemish resentments, as it remained unimplemented. Expressions of this resentment became particularly loud after 1940, when the number of Flemings—and of Flemings who had enjoyed school education in Dutch instead of French—entering into colonial service increased significantly (Van Bilsen 1949). From that moment on Flemings in the Congo reacted more forcefully than before to the colonial government’s inactivity with regard to this 1908 commitment.[6] In fact, only one language-related decree was ever issued, and, for that matter, 44 years overdue, namely on February 15, 1957.[7] It allowed Flemings to be heard and tried in Dutch in colonial courtrooms. In 1957-1958, attempts were made to design a similar decree for communication in the administration, but this decree never saw the light before Congolese independence in 1960. Before 1957, some, mostly Francophone, law specialists argued that the absence of decrees was unproblematic, as it entailed that the linguistic freedom mentioned in the Charter’s first sentence was still “complete” with regard to private language use, and that for official communication the absence of decrees simply meant that the continued use of French, inherited from times prior to 1908, was “sanctioned by consuetude” (i.a. Malengreau 1953).

In this context, school education for Flemish children growing up in the Congo also deserves some attention. Whereas in Flanders children had been able to receive (parts of) their schooling in Dutch since the 1880s, in the Congo they were compelled to go to French-speaking primary and secondary schools (for whites)[8] until 1948. In that year, some primary schools where split up into a French-speaking and a Dutch-speaking section. By 1956, only twenty-four out of the forty-three primary schools for whites in the entire, vast colony, and eight out of the twenty-five secondary schools, had separate French- and Dutch-speaking sections (De Wilde 1958:83).

During the 1950s, a Congolese elite protested against the 1957 decree for the bilingualization of the courts and the preparation of a similar decree for the administration. Their fear was that the social and economic emancipation for which they had had to struggle so long, and of which the latest integration of more Congolese in the colonial administration had been a first success, would now be rescinded. A few, very local, exceptions notwithstanding, the Congolese had never been taught Dutch in the colonial schools for them, French and African languages from the start being the only mediums and subjects of education. If Dutch was to become an official, and thus enforceable, language alongside French in colonial society, Congolese clerks would be denied jobs and career opportunities, as they would not be able to serve the Flemish colonials. During a meeting of the Government Council held in Leopoldville in December 1957, the Congolese representative Anekonzapa argued:

The linguistic conflict is a Belgian metropolitan thing. We don’t want any of it. We see in it a great danger and we demand an official guarantee that the Flemish language will never be imposed on us.[9]

When this Congolese elite rose to compose the governing bodies of the new independent Congo after June 1960, their umbrage with the former Flemish claims manifested itself immediately. For instance in September 1960, earlier Flemish endeavors, that had taken no less than four years of discussions and debates, to bilingualize the University of Elisabethville, were curtailed with one stroke of a pen, changing the statutes to clearly indicate that French was to be the only language of instruction in the university (Govaerts 2010). Secondly, on January 7, 1961, the new government divulged a circular ordering the removal of Dutch from all official documents, as well as from announcements, messages, and signposts in public places, and to replace them with monolingual French ones (Matumele 1987:189; Kazadi 1987:152).

Intersections and cross-influences

During the Belgian political debates of 1908 on the Colonial Charter, parliament member Adelfons Henderickx and others argued that the Congo would eventually be peopled by a majority of Belgians from Flanders, where at the time birth rates were booming and jobs scarce. Henderickx also expected a demographic contribution to come from “other colonists of the Dutch tribe,”[10] among whom most importantly “the Dutch Afrikaanders,” whom he qualified as “a tenacious race.” He referred to negotiations that had already taken place between Afrikaners living in Angola since 1874, but dissatisfied with the Portuguese rule (Stassen 2009, 2015), and the Belgian colonial authorities, with the aim of organizing their permanent settlement in the south-western Congo. Henderickx mentioned that this project was curtailed by the death of one of the Afrikaner leaders, but that, if it was to be revived, one should remember that they had laid down the condition that “the Dutch language, to which the Boers are so attached, should have, in the Congo, the same rights as French.”

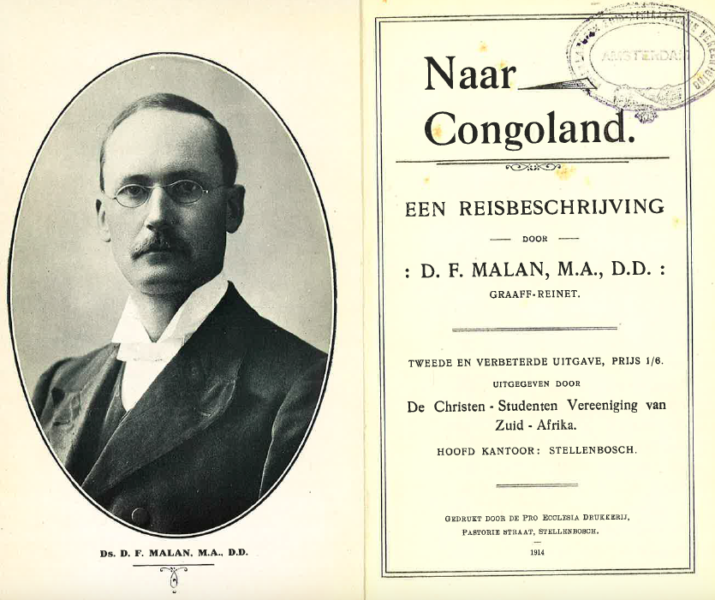

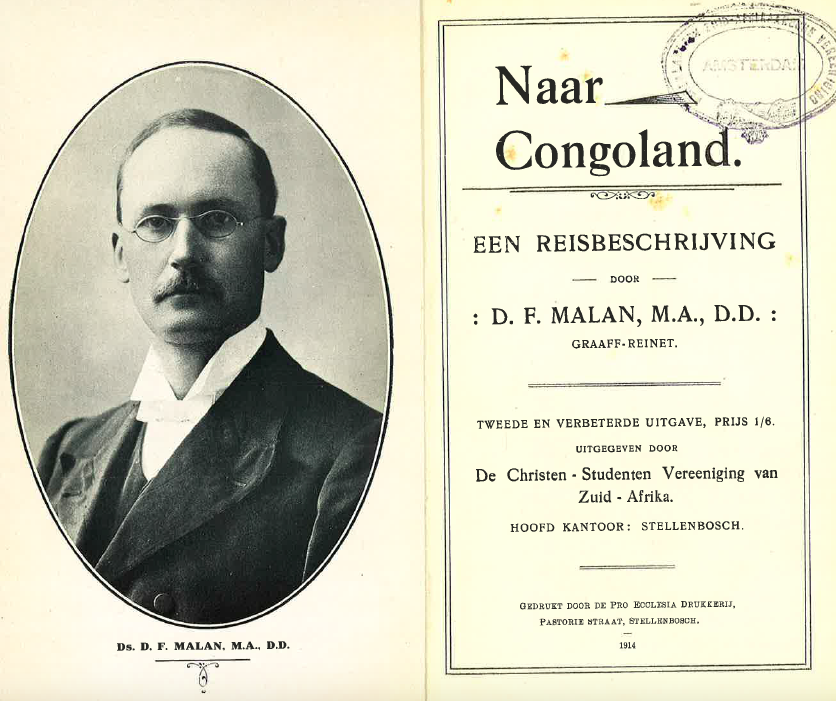

In 1912, the later South-African prime minister D.F. Malan made a trip to the Rhodesias in order to assess the situation of Afrikaners who had settled there (Roux 1988), particularly that of his fellow members of the Dutch Reformed Church (Korf 2010, Malan 1914). He noticed that almost all the Afrikaner families he met wished to migrate further north to the Belgian Congo on account of the new official status Dutch had gained there since its 1908 Charter. Malan himself instead pleaded for an Afrikaner struggle for the recognition of Dutch as co-official language (alongside English) in the Rhodesias. He argued that this would allow for a united, concatenated Dutch-speaking zone in the whole of sub-Saharan Africa:

If now Rhodesia granted the same rights to the language of an important section of its population [i.e. the Afrikaners], the Dutch language would be the official language of the continent from Cape Town up to the Ubangi river, which is up to the borders of the Sudan, i.e. a distance of 3,000 miles (1914:37).

Malan’s vision of an ethnolinguistic brotherhood ran closely parallel with that imagined by Henderickx and his colleagues in Belgian parliament. They, too, dreamed openly of a great nation of Dutch speakers spreading contiguously from the equator down to the southern tip of the African continent.

Around the same time, in 1914, the Belgian politician Louis Franck made a trip to Africa in order to sharpen his knowledge of the continent and colonial policies. Remarkably, his trip brought him first to South Africa. In Cape Town, Stellenbosch, and Pretoria, he gave speeches for audiences of Afrikaners on the Flemish struggle for linguistic equality in Belgium, all of which the Afrikaners received with great enthusiasm (Walraet 1952:331). He was the personal guest of D.F. Malan, as well as of the later prime ministers J. Smuts and J.B.M. Hertzog and ex-president M.T. Steyn. He had conversations with each of these political thinkers on matters of language, Flemish-Afrikaner identity, and their belief in the desirability of racial segregation. From South Africa, he travelled north through the Rhodesias to Katanga in the Belgian Congo, an itinerary very reminiscent of the one Malan had chosen two years earlier.

Louis Franck became Minister of Colonies in 1918, remaining in office until 1924. His South-African experiences influenced his colonial policies substantially. He referred to the 1908 Colonial Charter rather optimistically arguing that the Flemings in the Congo now had “exactly the same” linguistic rights as in Belgium (Franck 1929:1), enjoying the possibility to address the administration and courts in their own language in all situations (which was not the case). He added that this full and real official status of Dutch had also reached the ears of his friend Jan Smuts in South Africa. He reported Smuts to have reacted in truly exalted terms:

one day, this made the eminent South African statesman General Smuts say that the Dutch language had raised to the rank of official language from the Cape to the Equator. (Franck 1929:1)

In conclusion, the history of Dutch in colonial Africa in principle unfolds along two different tracks in two different parts of the continent, one in the Belgian Congo, the other in South Africa. But there were remarkable cross-references between historical events on each track, and junctures at which the actors informed and strongly influenced each other’s thinking. In the limited space available to me here, I have only been able to point at some examples of this, but I hope to have aroused the reader’s interest in this little-known part of Africa’s past.

Michael Meeuwis studied African History & Philology at Ghent University and general linguistics at the universities of Amsterdam and Antwerp. He obtained his PhD in 1997 from the University of Antwerp with a thesis on the sociolinguistics of the Congolese community in Flanders, after which he was professor of anthropological linguistics at the University of Amsterdam. Since 2002 he has been Professor of African languages at Ghent University, where he teaches Lingala, as well as courses on the history of colonial and missionary linguistics in Africa. He has published widely on the grammar and political history of Lingala, South-African sociolinguistics, the history of the science of linguistics in Africa, missionary linguistics in the Belgian Congo, and African colonial and present language policies. His list of publications can be consulted at

This account is based on a series of more detailed academic articles Michael Meeuwis has (co-)authored over the last years, namely Meeuwis (2007, 2011a, b, 2015a, b, 2016) and Jaspers & Meeuwis (2018).

References:

BAND. 1956. De taalregeling in Kongo: Documenten. Leopoldville: Band.

Boon, J. 1946. Joris van Geel, een Vlaamsch martelaar in het oud-koninkrijk Kongo (1617-1652). Tielt: Lannoo.

Cornelis, S. 1991. Stanley au service de Léopold II: La fondation de l’Etat Indépendant du Congo (1878-1885). In H.M. Stanley: Explorateur au service du Roi, ed. S. Cornelis, 41-60. Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa.

De Wilde, L.O.J. 1958. Cultuur en levenskansen van Vlaanderen in Kongo. In Les problèmes des langues au Congo-Belge et au Ruanda-Urundi, ed. Stichting-Lodewijk De Raet, 67-95. Brussels: Stichting LDR.

Deumert, A. 2004. Language standardization and language change: The dynamics of Cape Dutch. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

du Plessis, T. 1986. Afrikaans in beweging. Bloemfontein: Patmos.

Franck, L. 1929. La question des langues au Congo. Le Flambeau 12(9): 1-9.

Govaerts, B. 2007. Wilfried Borms in Belgisch-Congo: Een eenmansgevecht voor het Nederlands in de kolonie? Wetenschappelijke Tijdingen 66(1): 6-33.

-. 2008. De zaak van Rechter Grootaert en de strijd om het Nederlands in Belgisch-Congo. Wetenschappelijke Tijdingen 67(1): 7-46.

-. 2010. De Universiteit van Elisabethstad (1956-1960): Arena van het laatste Vlaamse gevecht in Belgisch-Congo. Wetenschappelijke Tijdingen 69(2): 107-146.

Heyse, T. 1955-1957. Congo Belge et Ruanda-Urundi: Notes de droit public et commentaires de la Charte Coloniale, Volume II. Brussels: G. Van Campenhout.

Jaspers, J. & M. Meeuwis. 2018. ‘We don’t need another Afrikaans’: Adequation and distinction in South-African and Flemish language policies. Sociolinguistic Studies 12(3).

Kannemeyer, J.C. 1974. Die Afrikaanse bewegings. Pretoria: Academica.

Kazadi, N. 1987. Propos libre sur une politique linguistique zaïroise. Linguistique et Sciences Humaines 27: 150-155.

Kita, P.K.M. 1982. Colonisation et enseignement: Cas du Zaïre avant 1960. Bukavu: Ceruki.

Korf, L. 2010. D.F. Malan: A political biography. PhD, University of Stellenbosch.

Malan, D.F. 1914 [original 1913]. Naar Congoland: Een reisbeschrijving. Stellenbosch: De Christen-Studenten Vereeniging van Zuid-Afrika.

Malengreau, G. 1953. De l’emploi des langues en justice au Congo. Journals des Tribunaux d’Outre-Mer 4(31): 3-6.

Matumele, M.M. 1987. Langues nationales dans l’administration publique. Linguistique et Sciences Humaines 27: 186-190.

Meeuwis, M. 2007. Multilingualism as injustice: African claims on colonial language policies in the Belgian Congo. In Multilingualism and Exclusion: Policy, Practice and Prospects, ed. P. Cuvelier et al., 117-131. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

-. 2011a. Bilingual inequality: Linguistic rights and disenfranchisement in late Belgian colonization. Journal of Pragmatics 43(5): 1279-1287.

-. 2011b. The origins of Belgian colonial language policies in the Congo. Language Matters 42(2): 190-206.

-. 2015a. From the Cape to the Congo and back: Afrikaners and Flemings in the struggle for Dutch in Africa (1874–1960). Language Matters 46(3): 325-343.

-. 2015b. Language legislation in the Belgian Colonial Charter of 1908: A textual-historical analysis. Language Policy 14(1): 49-65.

-. 2016. Taalstrijd in Afrika: het taalwetsartikel in het Koloniaal Charter van 1908 en de strijd van de Vlamingen en Afrikaners voor het Nederlands in Afrika tot 1960. Wetenschappelijke Tijdingen 75(1): 27-61.

Ponelis, F.A. 1993. The development of Afrikaans. Frankfurt: Lang.

-. 2005. Nederlands in Afrika: Het Afrikaans. In Wereldnederlands, ed. N. Van der Sijs, 15-30. Den Haag: Sdu.

Roberge, P.T. 2002. Afrikaans: Considering origins. In Language in South Africa, ed. R. Mesthrie, 79-103. Cambridge: Cambridge UP.

Roux, J.P. 1988. Die Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk in Zambië, 1895-1975. PhD, University of Pretoria.

Senelle, R. & E. Clément. 2009. Léopold II et la Charte coloniale (1885-1908). Wavre: Mols.

Stassen, N. 2009. Afrikaners in Angola: 1928-1975. Pretoria: Protea.

-. 2015. Die Dorslandtrek, 1874-1881. Pretoria: Protea.

Steyn, J.C. 1996. Afrikaner nationalism and choosing between Afrikaans and Dutch as cultural language. South African Journal of Linguistics 14(1): 7-24.

-. 2009. Die Afrikaans van die Bybelvertaling van 1933. Acta Theologica 29: 130-156.

-. 2014. ‘Ons gaan ʼn taal maak’: Afrikaans sedert die Patriot-jare. Pretoria: Kraal.

Van Bilsen, A.A.J. 1949. Voor een koloniale taalpolitiek: Demographische taaldruk uit België. De Spectator 18 February 1949: 4.

Van der Sijs, N. 2004. Taal als mensenwerk: Het ontstaan van het ABN. Den Haag: Sdu Uitgevers.

van Rensburg, C. 2015. Creating a standardised version of Afrikaans, the first 50 years. Tydskrif vir Geesteswetenskappe 55(3): 319-342.

van Sluijs, R. 2013. Afrikaans. In The survey of pidgin and creole languages, volume I, ed. S.M. Michaelis et al., 285-296. Oxford: Oxford UP.

Walraet, M. 1952. Franck, Louis. In Biographie Coloniale Belge III, 325-343. Brussels: Institut Royal Colonial Belge.

Wils, L. 1977. De taalpolitiek van Willem I. Bijdragen en Mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden 92(1): 81-87.

-. 1985. De taalpolitiek van Willem I. Wetenschappelijke Tijdingen 4(44): 193-201.

[1] I ignore the Flemish missionaries who travelled to the Kongo Kingdom in the 17th century, Joris van Geel and Erasmus van Veurne (Boon 1946), because of the non-structural presence of Dutch this entailed for the region.

[2] For purely linguistic accounts of the history of Afrikaans, see Roberge (2002) and van Sluijs (2013).

[3] Section 137 of the “South Africa Act” of 1909.

[4] Van Bilsen (1949) wrote that in 1949 no less than 70% of all missionaries in the Congo were Flemings.

[5] Article 3 of the Colonial Charter, officially the “Law on the Governance of the Belgian Congo of 18 October 1908”.

[6] For overviews of these reactions, see the 1956 special issue of the Flemish colonial magazine Band, as well as Govaerts (2007, 2008, 2010) and Meeuwis (2016).

[7] For the Congolese population, no such language decree was ever issued.

[8] Schools remained racially segregated until 1952, when mixed schools were officially made possible (Heyse 1955-1957:520; Kita 1982), but after which many still remained segregated in actual practice.

[9] Minutes of the meeting of the Government Council (Leopoldville) of December 31, 1957.

[10] All these quotes are from the original minutes of the Belgian Chamber of Representatives.

Photo:

Published on March 1, 2018.