This is part of our special feature on Nationalism, Nativism, and the Revolt Against Globalization.

Populists and people attracted to populist messages have a strong sense of home and belonging, as well as a vehement urge to return to a monocultural version of home, in which their culture will be protected from non-native “intruders.” Migrants emerge as perceived threats to the economic and welfare systems and to culture and tradition by, for instance, “Islamizing” their new European home countries. Artist Do-Ho-Suh uses translucent fabrics and mathematical processes to create works built around the idea of home, only his fabrics are collapsible, thereby questioning the connotations of “home” and “belonging” with the familiar, comforting, and safe. The perception of a safe home is closely linked with the populist view that women’s “intended role” is at home, as dutiful wife and mother, whereby any step outside the home context is threatened by sexual aggression. Korean-born artist, Insoon Ha’s work deals with this rhetoric of rape, the disturbance and aggression that so often marks today’s political agenda and reveals that we are far removed from gender equality.

–Nicole Shea for EuropeNow

Do Ho Suh

Since the beginning of his career during the 1990s, Suh’s practice has been informed by his own experiences of migration, responding to the impermanence, dislocation, and nostalgia he has felt at various points in his life. Suh is best known for his monochrome fabric sculptures that reconstruct to scale his former homes: his childhood Hanok-style home in Korea, a house in Rhode Island where he lived as a student, an apartment in Berlin he inhabited during a residency, and the New York apartment he rented for more than 20 years. Through the replication of these spaces, Suh examines how the body physically and emotionally inhabits and interacts with architecture, particularly domestic spaces. In his recreations of his homes, Suh’s memories are re-materialized in meticulous detail, but instead of brick and mortar, they are constructed in sheer fabric, as though a ghost or lingering remnant of the original. Along with Suh’s interest in the individual’s relationship to architectural space is one’s role within a larger community. For Suh, both our physical home and our communities not only provide security and a sense of belonging, but also inform the construction and definition of our very identity.

Doorknobs, Wieland Strasse, 18, 12159 Berlin, Germany, 2011, polyester fabric and stainless steel wire, 19.25 x 21.61 x 3.35 inches, 48.9 x 54.9 x 8.5 cm

Home within Home within Home within Home within Home, 2013, polyester fabric, metal frame, 602.36 x 505.12 x 510.63 inches, 1530 x 1283 x 1297 cm

Home Within Home – Prototype, 2009-2011, photo sensitive resin, 86.14 x 95.69 x 101.12 inches, 218.8 x 243.04 x 256.84 cm

Apt. A, Corridor and Staircase, 348 West 22nd Street, New York NY 10011, USA, 2011-2012, polyester fabric and stainless steel tubes, 383.46 x 66.14 x 457.87 inches, 974 x 168 x 1163 cm

Apt. A, Corridor and Staircase, 348 West 22nd Street, New York NY 10011, USA, 2011-2012, Corridor and Staircase: 96.46 x 66.14 x 488.19 inches, 245 x 168 x 1240 cm

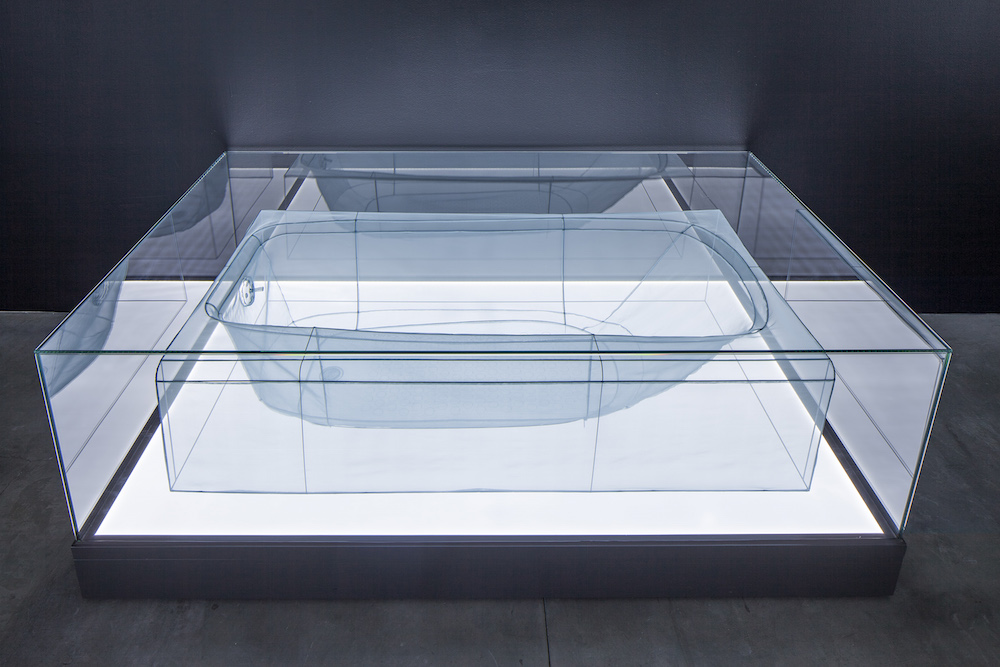

Bathtub, Apartment A, 348 West 22nd Street, New York, NY 10011, USA, 2013 polyester fabric, stainless steel wire, glass and display case with LED lighting 13.375 x 59.188 x 30.125 inches 34 x 150.3 x 76.5 cm

Do Ho Suh (b. 1962, Seoul, Korea; lives and works in London and Seoul) works across various media, creating fabric architecture, figurative sculpture, intricate drawings, and films that address questions of identity and belonging. Suh received a BFA in painting from Rhode Island School of Design in 1994 and an MFA in sculpture from Yale University in 1997. Solo exhibitions of his work have recently been organized at Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC (2018); Frist Center for the Visual Arts, Nashville, TN (2018); and Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, WI (2017).

Insoon Ha

Insoon Ha’s works are mired within brutality, hovering between the aftermath of assault and the moments before an act of aggression is set to transpire. She frequently explores the intersecting rubrics of the abject and post colonialism by utilizing hybridized forms that occupy and embody the liminal space between polarized positions. Most of the pieces that she creates, while often bloodless in deception, still manage to convey a certain debased essence of degradation.

In late 1937, over a period of six weeks, Imperial Japanese Army forces brutally murdered hundreds of thousands of people–including both soldiers and civilians– and sexually assaulted between 20,000 and 80,000 women in the Chinese city of Nanking. Entire families were massacred, with the elderly and infants targeted for execution, while tens of thousands of women were raped. The true nature of the massacre has been disputed and exploited for the purposes of propaganda by historical revisionists, apologists and Japanese nationalists. Some claim the numbers of deaths have been inflated, while others have denied that any massacre occurred.

Ha’s works have been informed by the historical trauma of “comfort women” who suffered enslavement, rape, sexual exploitation, silencing, and abandonment under Japan’s institutionalized system of sexual slavery during its World War II. More than 200,000 women and girls (the majority aged between 13 and 16), mostly Korean, abducted and forced into sexual service by the Japanese military and placed in comfort stations instituted and maintained by the Japanese government in northeast and southeast Asia.

Japan kidnapped women throughout the Asian continent to establish the comfort women system as an extension of the Rape of Nanking. In 1938, the first official comfort women stations of the Japanese army were set up near Nanjing. The Nanjing Massacre marked the starting point of the phenomenon of comfort women, which is deeply entwined with the history of Korea’s colonization.

Ha interrogates the ways in which the historical legacies of systemic rape, sexual violence, and other crimes committed against humanity perpetuate gender-based, racist, and classist ideologies which laid a foundation of violent cultural practices.

1~2. Stay, A sink is filled with water; its drain goes up to the level of the top of the sink, so the water stays there. Sink, Drain, Water. 19 x 22 x 30 in. 2009

1~2. Stay, A sink is filled with water; its drain goes up to the level of the top of the sink, so the water stays there. Sink, Drain, Water. 19 x 22 x 30 in. 2009

3~5. Dripping, A white slip embroidered with red threads that extend beneath it and are connected to about 100 needles.Needles, Slip, Red thread. 2 x 17 x 62 in. 2009

3~5. Dripping, A white slip embroidered with red threads that extend beneath it and are connected to about 100 needles.Needles, Slip, Red thread. 2 x 17 x 62 in. 2009

6~7. Drain, A mannequin wears a red skirt with a drain on it. In the middle of a chair, a sharp metal horn is protruding. Chair, Metal, Skirt, Drain. Mannequin. 2009

6~7. Drain, A mannequin wears a red skirt with a drain on it. In the middle of a chair, a sharp metal horn is protruding. Chair, Metal, Skirt, Drain. Mannequin. 2009

8~9. After it, A woman knelt down, headless, with an infant’s leg protruding from her back. Hydrocal, Dry wall. 2.4 x 1.6 x 1.8 ft. 2004

8~9. After it, A woman knelt down, headless, with an infant’s leg protruding from her back. Hydrocal, Dry wall. 2.4 x 1.6 x 1.8 ft. 2004

Insoon Ha was born in Seoul, South Korea, and currently lives in Toronto, Canada. She works across various media in sculpture, installation, performance, photography and video. Her work has been exhibited internationally, including selected exhibitions in Canada, Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, Latitude 53, La Centrale gallery powerhouse, A Space Gallery, McMaster Museum of Art, Center [3] gallery and Albright-Knox Art Museum, Cepa gallery, Big Orbit gallery in Buffalo, NY, 621 Gallery in Tallahassee, FL, Whanki Museum, Seoul, Korea. She holds both a BFA and MFA from the University of Seoul in Sculpture, and a second MFA from the State University of New York at Buffalo in Fine Arts. She received numerous grants from the Canada Council for the Arts, Ontario Arts Council and Toronto Arts Council for her project.

Nicole Shea ran CenterArts Gallery in Newburgh from 2009-2012 and later incorporated her arts experience into the leadership training at West Point. In 2015, she founded a large-scale sculpture walk outside the gates of West Point, which she has been curating together with the founding members of Collaborative Concepts in a community effort to revitalize the area via the arts. She is also Executive Editor of EuropeNow and Director of the Council for European Studies.

Published on February 1, 2018.