I started the Netflix television series Dark expecting a European mystery detective series in the model of The Bridge, The Missing, or countless other shows with one-word titles. It has its flaws. As the plot unfolds it reveals itself to be a sort of Back to the Future meets Angels and Demons, with a little bit of True Detective’s Neitchizean ponderings mixed in. It rains an ungodly amount in the fictional town of Winden and no one uses umbrellas—or minds standing outside getting soaked. But what sets Dark apart from its cohort is that its drama stems from an engagement with German energy politics.

In 2011, shortly after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, Germany began a plan to phase out nuclear energy, citing the possibility of unforeseen risk. The plan’s goal, still in place, is to close all of Germany’s nuclear power plants by the end of 2022 (Die Bundesregierung 2017). As of 2018, Germany has seven nuclear energy facilities, all located in the former West Germany and built during the 1970’s and 80’s, with operations beginning in the mid- to late- 1980’s. Two additional facilities have already ceased operation, one in 2015 and one in 2017 (Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit 2018).

Winden, the fictional town where the show is set, is the site of a nuclear power plant. The show begins in 2019, and we quickly learn that the power plant is slated to shut down the following year, 2020. English speaking viewers of Dark might notice that the Winden power plant is referred to as the AKW, an acronym which stands for Atomkraftwerk, or nuclear power plant; to a German speaker, this has a more sinister ring, as if “the plant” were so monolithic it didn’t need a proper name.

The plan to phase out nuclear energy is part of a larger push towards dependence on renewable energy, which began with the passage of the Renewable Energy Law (called the EEG, for Erneubare Energien Gesetz) in 2000. The law provided financial incentives to renewable energy producers, with the goal of increasing their share of the energy market. Since the EEG’s passage, the percentage of Germany’s energy produced by renewables has risen steadily, from 6.2 percent in 2000 to 31.5 percent in 2016, the latest available statistics (Arbeitsgruppe Erneubare Energien Statistik 2017). The federal government’s goal is to have 40 percent of Germany’s energy provided by renewable sources by 2025, and 80 percent of its energy renewable by 2050. The shrinking remainder would still be powered by fossil fuels (Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie 2017).

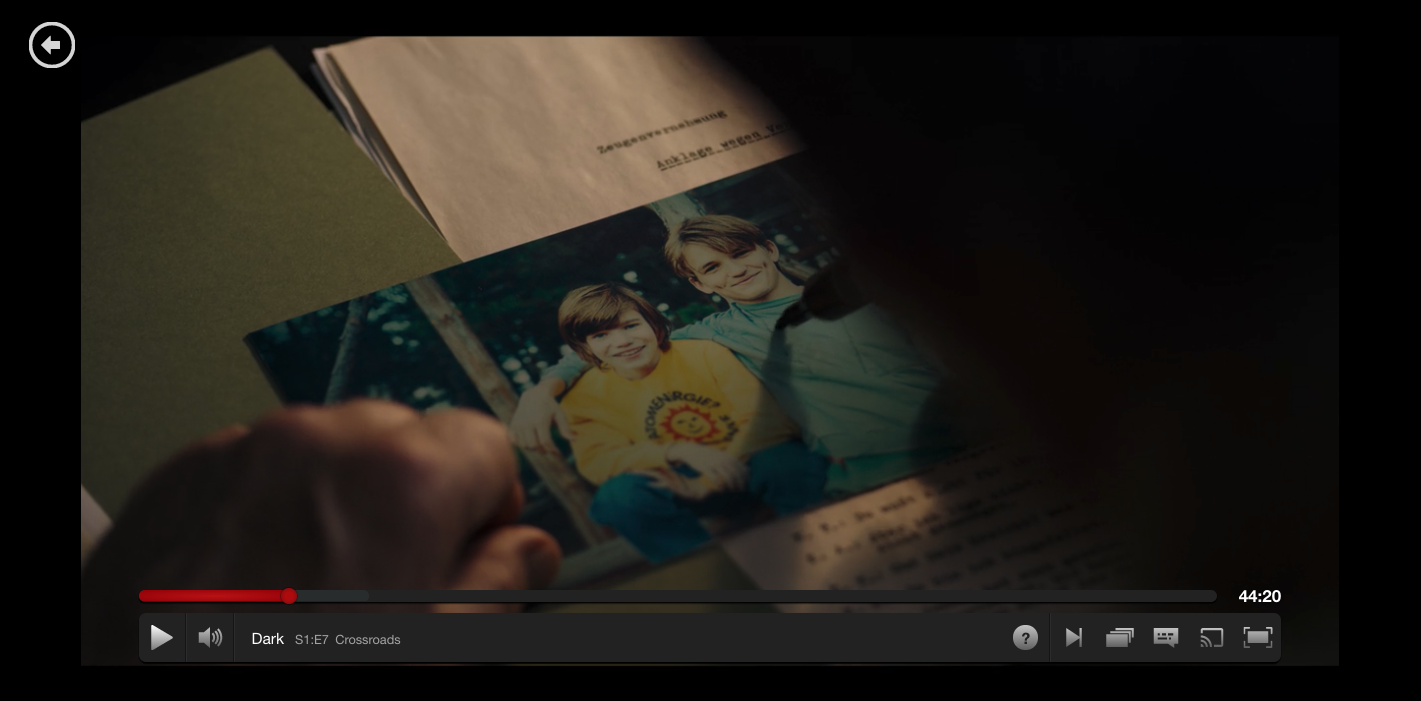

The EEG has brought changes to both Germany’s physical landscape—the proliferation of fields filled with wind turbines and solar panels—and to the everyday life of its citizens, as consumer energy costs have risen precipitously since 2011. Yet Dark illustrates that energy production’s intrusion into social life is nothing new. [SPOILERS] The show’s central premise is that a cave in Winden, once used to house nuclear materials, holds a wormhole that connects three time periods: 1953, 1986, and 2019. In 2019, teenage boys begin disappearing in Winden. We soon discover that this has happened before. Mads Nielsen, the younger brother of detective Ulrich Nielsen, disappeared in 1986. Mads disappeared—and reappeared in 2019—wearing a shirt from Germany’s anti-nuclear energy movement. The logo, seen on shirts, stickers, and other political paraphernalia, depicts a smiling red sun against a yellow background, surrounded by the words “Nuclear energy, no thank you!” Designed by a Danish university student in 1972 (Ausgestrahlt 2017), the logo remains ubiquitous in Germany, and is immediately recognizable. While Mads wears his anti-nuclear shirt in 1986, Winden residents discuss the ramifications of the recent Chernobyl disaster and their fears over the environmental destruction that it could bring; Winden’s ubiquitous rain might turn to acid.

Figure 1: Dark, Episode 7 screenshot: A photo of Mads Nielsen (left) from his 1986 police file shows him in an anti-nuclear energy shirt

By illustrating a direct link between 1953’s nuclear enthusiasm, when the plant was first built, 1986’s nuclear anxieties, and the present day, Dark presents a clear genealogy: from making headstrong decisions based solely on economics, to seeing the dangers of nuclear energy firsthand, to finally learning from the past to divest ourselves from nuclear power and limit future destruction. At the same time, there is a very German engagement with the non-linear nature of history, beginning with the events of 1986.

The wormhole connecting the show’s three eras opened in 1986, when Winden’s power plant executives began illegally storing nuclear waste in a cave, thereby inadvertently creating passages in time. (The struggles of the plant’s first female CEO who discovers this illegal trove provide a pointed and necessary commentary on workplace gender dynamics.) Yet as many scholars have discussed, most notably Hans Gumbrecht, W.G. Sebald, and Andreas Huyssen, Germany’s approach to history is at once cyclical and occlusive: we know that there is a traumatic past—as evidenced by the silence of an older generation, the physical destruction of cities, or monuments to the dead, respectively—but its details and broader context are largely omitted from the things—silence, rubble, statues—which index it.

Much of post-war German memory politics—Adorno’s calls for an Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit, a working-through of the past—are in response to this culture of silence in the face of clear evidence of trauma, complicity, or destruction. In On the Natural History of Destruction, Sebald recounts Swedish journalist Stig Dagerman’s 1946 trip to Hamburg; riding through the ruined, bombed-out landscape, Dagerman gave himself away as a foreigner, Sebald says, “because he looked out” (Sebald 2003, 103, italics in original).

Gumbrecht, in his 2013 book After 1945: Latency as the Origin of the Present, calls this approach to history the temporality of latency. Growing up in the 1950’s and 60’s, the adults in Gumbrecht’s life carried around the secrets of their wartime involvement—one friend of Gumbrecht’s father was a fairly high-ranking member of the Nazi party; a peer, known as S., had a grandfather who buried mysterious glass containers in the woods behind his house. Gumbrecht’s parents, grandparents, teachers, and family friends must have had wartime experiences simply by virtue of having lived through the war. But the topic was taboo, and the details of those experiences never came to light—even when, eventually, Gumbrecht grows up and starts asking questions. Like many Germans of the ’68 generation, Gumbrecht sought to build a new Germany based on openness and tolerance, but at the same time, he was forced to live in the shadow of the recent yet inaccessible past. The intergenerational tensions that resulted from World War II upended the steady temporal progression of past, present, and future. In an age of latency, the present was where you lived in wait of a future where the past would finally reveal itself to you in full.

Dark presents a physical analogue to this model of emotional suppression. The nuclear waste and the wormholes it opens create pain and confusion for Winden residents in all three time periods: missing boys, mysterious dead bodies—perhaps Chinese, one 1953 detective suggest, because their strange clothes have tags that say “Made in China”—mass die-off of animals, suspicion of friends and neighbors. Residents hope that some something—something heretofore secret—will come to light and explain the mysterious occurrences that have been plaguing their town. An answer would mean that these phenomena could be combatted and controlled.

Latency is a consequence of the fact that suppression—be it of a Nazi past, or the existence of nuclear waste—still allows unease and distrust to seep out even when something is hidden, perhaps even more so than if that suppressed thing had been properly disposed of. At the same time, suppression creates a separation between the suppressed thing—that mystery at the core of latency—and its effects. In an age of latency, it is impossible to escape the past, and impossible to deny the consequences of the past, even when the details of that past might die with those who knew them. In this way, latency both minimizes and maximizes the suppressed thing: it is wiped of detail, like the unknown contents of a bright yellow barrel, but whatever it is, it is the source of current problems.

Furthermore, in an age of latency, it is not the past in its infinite fullness that comes to characterize the present, but rather one particular historical moment. Unlike in other time travel films and TV shows like Back to the Future, Winden’s residents cannot dial their caves to whatever time period they’d like to visit—one character actually says of the cave’s limited time travel options, “This is no DeLorean.” It is this past, this series of two consequential moments—the moment of the plant’s inception in 1953, and the moment when nuclear energy’s dangers could no longer be contained in 1986—that have wrought the present moment: its guilt and suspicion, its panic and uncertainty, both economic and existential.

In applying the logic of latency to the energy industry, Dark makes it clear that that which is not brought to light will bear unpleasant consequences. But moreover, it makes clear that Nazism is not the 20th century’s only shameful moment, and not its only destructive legacy.

Despite being set in the present, an era of environmental awareness and advocacy in Germany, Dark ends with a reminder that even the most well-intentioned plans can be disrupted by seeds of destruction planted in the past. The protagonist Jonas, using a device that runs on material stolen from the hidden nuclear waste, opens up a new wormhole in the cave, this one connecting three different eras: 1986, 2019, and, we presume, though it is never made explicit, 2052. (The wormhole connects time periods in 33 year increments, a Biblical reference that conveniently tracks seminal moments in Germany’s energy history—construction on the Winden plant begins in 1953, which puts it on track to open around 1957, the year that Germany’s first nuclear reactor began operation [Der Spiegel 2000].) The Winden of 2052 is a gray, post-apocalyptic landscape populated by roving, rag-tag militias. The nuclear plant is in ruins, and burned-out signs warn of radiation contamination in multiple languages. As the episode’s title, Alpha and Omega, hints at, this is the natural conclusion of the era that began in 1986. In 1953, nuclear energy was merely a utopian dream, the promise of an energy source that would power the rise of Germany’s post-war economy. By 1986, nuclear energy had become a ubiquitous fact of life. And despite the efforts to phase it out in 2019, that ubiquity—the millions of tons of waste already produced, the reactors across the country that would have to be carefully dismantled—had already set in motion events that would lead to vast environmental and social destruction.

In German, the reunification of East and West Germany in 1991 is referred to as the “Turning Point,” or die Wende. Today, the shift in energy dependence is referred to as the “Energy Turning Point,” die Energiewende, a turn of phrase that positions it as the next monumental, deeply consequential historical moment. Dark, with its drama centered on the consequences of nuclear energy production—social and economic consequences, in addition to those more speculative and supernatural—illustrates the degree to which changing energy politics serve as the backdrop to everyday life in Germany. One hopes that the show can export Germany’s attention to energy politics to an international audience.

Samantha Fox is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Anthropology at Columbia University and a Mellon-CES Dissertation Completion Fellow.

References:

Arbeitsgruppe Erneubare Energien Statistik, Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie.

“Entwicklung Der Erneubaren Energien in Deutschland Im Jahr 2016,” December 2017.

Ausgestrahlt: Gemeinsam Gegen Atomenergie. “‘Atomkraft? Nein Danke!’ Und Eine Lachende

Sonne,” 2017. https://www.ausgestrahlt.de/ueber-uns/anti-atom-sonne/.

Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit. “Atomkraftwerke in

Deutschland,” January 11, 2018. http://www.bmub.bund.de/themen/atomenergie

strahlenschutz/nukleare-sicherheit/aufsicht-ueber-kernkraftwerke/kernkraftwerke-in-deutschland/.

Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie. “Die Nächste Phase Der Energiewende Kann

Beginnen,” 2017. http://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Dossier/energiewende.html.

Der Spiegel Staff. “Kernforschung: Aus Für Das Garchinger Atom-Ei.” Der Spiegel, July 25,

Die Bundesregierung. “Energiewende: Fragen Und Antworten, Kernkraft,” 2017.

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. After 1945: Latency as Origin of the Present. Stanford University

Press, 2013.

Huyssen, Andreas. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. 1 edition.

Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 2003.

Odar, Baran bo, and Jantje Friese. “Dark.” Netflix, December 2017.

Sebald, W. G. On the Natural History of Destruction. Random House Publishing Group, 2003.

Published on February 1, 2018.