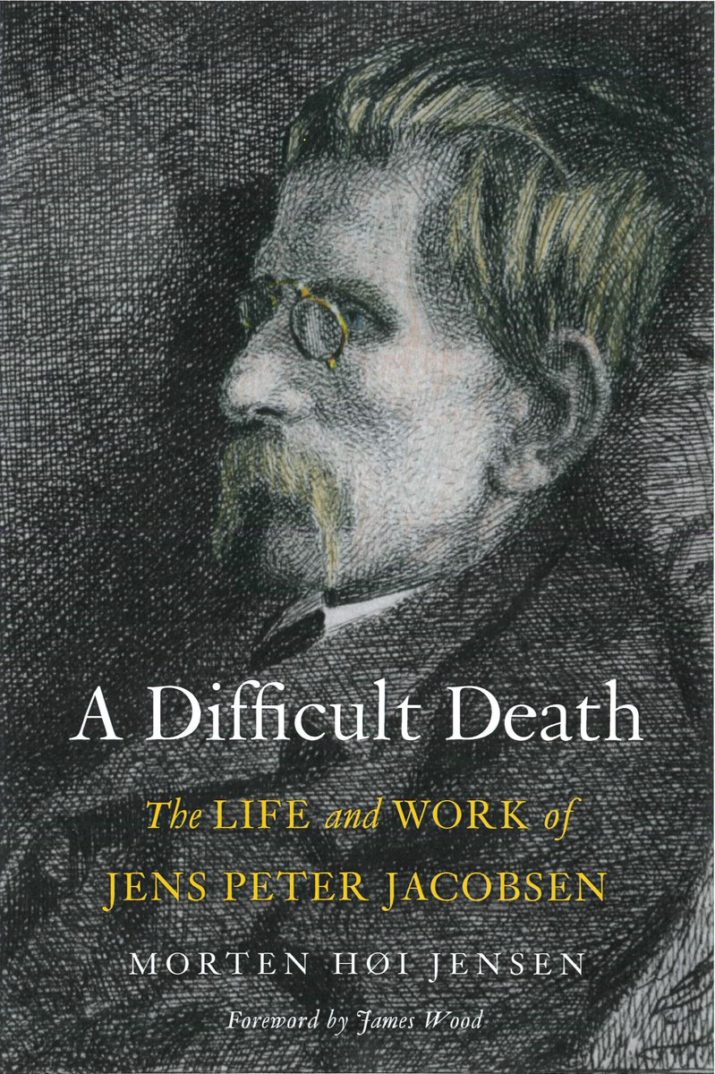

This new literary biography of Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen is a crisp introduction to a major Northern European writer who is ripe for rediscovery. A Difficult Death: The Life and Work of Jens Peter Jacobsen by Morten Høi Jensen beautifully illuminates a writer who was an inspiration to an entire generation of European modernists such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, James Joyce, and Knut Hamsun, even though he is largely unknown today. Jens Peter Jacobsen produced only two novels, several stories, and some poetry before succumbing in 1885 to “consumption” in a northern province of Jutland at age thirty-eight. This first critical study of Jacobsen in English is an engaging synthesis of biography, literary history, and cultural study, appetizingly written, and leaving the reader hungrily reaching to the shelves for the Danish classics, Marie Grubbe (1876) and Niels Lyhne (1880). The title phrase, A Difficult Death, which alludes to Jacobsen’s own fate, are haunting words from last line of Niels Lyhne (a work originally conceived of as “The Atheist”), describing the protagonist’s disquieting death without the comfort of religious faith.

This new literary biography of Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen is a crisp introduction to a major Northern European writer who is ripe for rediscovery. A Difficult Death: The Life and Work of Jens Peter Jacobsen by Morten Høi Jensen beautifully illuminates a writer who was an inspiration to an entire generation of European modernists such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Thomas Mann, James Joyce, and Knut Hamsun, even though he is largely unknown today. Jens Peter Jacobsen produced only two novels, several stories, and some poetry before succumbing in 1885 to “consumption” in a northern province of Jutland at age thirty-eight. This first critical study of Jacobsen in English is an engaging synthesis of biography, literary history, and cultural study, appetizingly written, and leaving the reader hungrily reaching to the shelves for the Danish classics, Marie Grubbe (1876) and Niels Lyhne (1880). The title phrase, A Difficult Death, which alludes to Jacobsen’s own fate, are haunting words from last line of Niels Lyhne (a work originally conceived of as “The Atheist”), describing the protagonist’s disquieting death without the comfort of religious faith.

Jens Peter Jacobsen belonged to that progressive European era of ideas, known in Scandinavian letters as the “Modern Breakthrough.” Sparked by the lectures of Denmark’s influential literary critic Georg Brandes at the University of Copenhagen, the Modern Breakthrough was a coming of age for the Nordic literary world. Brandes railed from the lectern that modern literature should show that it was alive by “putting problems to debate.” It was the era of Charles Darwin, John Stuart Mill, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Emile Zola. In the 1870s and ’80s, atheism and radical thinking rocked Copenhagen (“the little Paris of the North”), the city where Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House premiered in 1879. Here, Jens Peter Jacobsen also earned a distinction, “the foremost Danish champion of Darwin” (42). The writer was a skilled botanist (awarded Copenhagen University’s Gold Medal in 1873 for his pioneering study of algae in Denmark’s bogs and wetlands) and the translator of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species and The Descent of Man. Jacobsen daringly published essays intended to educate general readers about Darwinian theory in the early 1870s. This radical new thinking in Europe was “like bombs under the traditional Christian understanding of humanity” (41), writes Jensen gleefully. Thus, Jacobsen’s literary work melded poetry with a scientific understanding of the natural world and his literary work was later canonized as the “first naturalistic prose in Danish literature” (65). Although Georg Brandes remained a supporter until the poet’s untimely death, Jacobsen’s literary work is not driven by any polemic – in fact, Jacobsen consistently steered away from ideology and politics.

Jacobsen’s first published story, “Mogens,” is lush, painterly prose saturated with botanical color and delicate form. In the opening passages, the reader experiences a vision of a man (Mogens) resting in the roots of a large Oak; his figure merges with nature. But, the story of Mogens – as Jensen points out – is not romantic, but one of uprooting and modern disorientation that engages a central modern motif: the estrangement of the Self from life itself. In this discussion of Jacobsen’s innovative prose, Jensen’s critical study is often reliant on the award-winning translations of Tiina Nunnally. Thankfully, Nunnally’s eloquent translations from the original Danish will convince English language readers of Jens Peter Jacobsen’s poetic artistry.

Strangely, Jens Peter Jacobsen’s breakthrough novel was a sensuous work of historical fiction. Marie Grubbe – Seventeenth Century Interiors was a sensation at its publication in 1876, and soon hailed as the “first major work of the Modern Breakthrough” (105). Akin to Gustav Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Jacobsen’s first novel may have inspired August Strindberg’s drama, Miss Julie, 1888. The historical subject of Jacobsen’s novel was provocative in its day – a Danish noblewoman fallen from aristocratic marriage to a lowly union with an abusive ferryman. Filled with rich historical detail, the scenic episodes of Jacobsen’s first novel disrupt the structure of the nineteenth-century Bildungsroman. Marie Grubbe is a series of fragmented scenes, lushly depicted “interiors,” which capture the downward spiral of a woman’s life (yet as Marie is socially and physically degraded, the author suggests that her personal happiness increases). Jacobsen’s “naturalistic” portrait of Marie Grubbe has long presented readers with a self-destructive enigma. Jensen insightfully points out that Marie Grubbe’s physical desires and masochistic behavior ultimately do not present a consistent whole of “character,” as expected by readers of 1870s. Instead, Marie’s behavior demonstrates the mutability, or lack of wholeness, of the human character – this was something that the scientist Jacobsen observed, and it was something that Strindberg would later write about in his famous foreword to Miss Julie, in which he coins the phrase, “the characterless character.” Whether the reader of A Difficult Death is a novice or a scholar of Scandinavian letters, Jensen’s critical insights serve as wonderful revelations and welcome observations. Fortunately, for today’s reader of Jacobsen, Marie Grubbe: Seventeenth Century Interiors is recently available in a new English translation.

Niels Lyhne (1880), Jacobsen’s second novel, ranks as the most significant of his works. Jensen deems it “the most death haunted novel in European literature” (121). The protagonist, Niels Lyhne, endures a tragic existence (suffering no less than seven deaths of his nearest kin, including his wife and young child in short sequence), without the comfort of the Christian faith (which he has denounced in his youth), until he is fatally wounded as a volunteer soldier in the Dano-Prussian War of 1864 (a crushing defeat for the Danes). In the last line of the novel, Jacobsen’s disquieting words about Niels Lyhne remain with the reader (perfectly translated by Nunnally): “And finally he died the death – the difficult death” (141). Morten Høi Jensen notes with customary clarity, that “Niels Lyhne […] is an astonishingly candid and full-blooded account of the ambiguity of atheism” (141) and adds gingerly that “Freud loved it” (146). Such comments are among the many pithy references with which Jensen enriches this book. In his reflections on the modernity of the novel’s form, Jensen observes that, in Niels Lyhne, Jens Peter Jacobsen “dispenses with inherited novelistic furniture” (132), and he argues for Niels Lyhne as the first truly modern novel, naming its radical fragmentation of style, which was later “stream-lined into form by the likes of Hamsun, Rilke, Joyce and Mann” (132).

Clearly, Morten Høi Jensen owes a debt to Danish biographers and scholars of Jens Peter Jacobsen, who are generously acknowledged in this work. His study is not an archival study of new primary sources, nor radically new readings of Jacobsen’s literary texts. Most of the quotations are cited from previous studies of Jacobsen. It is Jensen’s crisp and concise writing and wit, which distinguish his marvelous contextualization of the intellectual, cultural, and social worlds in which Jens Peter Jacobsen moved and breathed (with some difficulty). Jensen draws vivid portraits of the nineteenth-century literary contemporaries of Jacobsen – so that they spring from the pages. Indeed, it is joyful to reacquaint oneself in the Danish capital with Herman Bang, Henrik Ibsen, August Strindberg, Holger Drachmann, Alexander Kielland, Amalie Skram, and to learn of Rilke’s rain-soaked months in Denmark in 1904 (carrying a copy of Niels Lyhne in his pocket) in pursuit of Jacobsen’s city and the Danish language. No less, Jensen’s positioning of Jacobsen among European prose modernists is a vital contribution to the study of Jacobsen’s literary work. Jensen moves his readers gracefully between German, French, English, and Scandinavian literary worlds and cultural contexts. This new critical study allows readers to appreciate Denmark’s Jens Peter Jacobsen, who died quietly in the northern province of Thy, as one of Europe’s literary giants—and it makes us thirsty to read more. With a rich foreword by James Wood, A Difficult Death must not be missed.

Reviewed by Marianne Stecher, The University of Washington

A Difficult Death: The Life and Work of Jens Peter Jacobsen

by Morten Høi Jensen

Publisher: Yale University Press

Hardcover / 272 pages / 2017

ISBN: 9780300218930

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on December 6, 2017.