The European Union’s Fight Against Terrorism: Discourse, Policies and Identity by Christopher Baker-Beall

This is part of our special feature on The Crisis of European Integration.

This is part of our special feature on The Crisis of European Integration.

Since the Charlie Hebdo attack in November 2015, several EU member states have been hit by episodes of jihadist terrorist violence (France, Belgium, Germany, UK, Sweden). Although mainstream media reports only some of these episodes, the latest report released by EUROPOL in July 2016 has provided a systematic analysis of terror attacks recorded in the EU in 2015, including jihadist, left-wing, right-wing, and separatist terrorism: only in 2015, six EU member states (Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, Spain, UK) faced 211 failed, foiled, and completed terrorist attacks (EUROPOL 016).

In parallel, 2016 was marked by EU’s inter-institutional negotiations on a new Directive on combatting terrorism, aiming to reinforce the EU’s legal framework in preventing terrorist attacks. The Directive also complements the current legislation on the rights for the victims of terrorism and envisages enhanced rules for information exchange between the member states related to terrorist offences gathered in criminal proceedings (Council of the EU 2016; 2017).

These aspects make Christopher Baker-Beall’s research topical, cogent, and timely. His book, titled The European Union’s Fight Against Terrorism: Discourse, Policies and Identity, offers not only an original interpretation of EU’s “fight against terrorism,” but also a detailed account of how it has been designed and re-designed since its development and institutionalization. It includes thorough references to the relevant actors involved, and documents epitomizing the stages of a 50-year trajectory of security policy-making. However, the focus of the book does not lie on the complex and manifold set of institutional and public policy responses conceived to tackle the threat of terrorism; quite differently, the book premises on the assumption the EU’s “fight against terrorism” is a political discourse: in other words, laws, agencies, and institutions work as long as they are accompanied and sustained by a language of counter-terrorism.

The author defines the discourse as a practice of meaning-making unfolding at specific sites “where knowledge about terrorism, as well as the identity of the EU, is (re)articulated, (re)produced and (re)enforced” (Baker-Beall 47). The language of EU’s “fight against terrorism” is embodied by statements, suppositions, beliefs, ideas, and all other discursive resources deployed to justify and legitimize counter-terrorism as a particular way of governing society. Such language of counter-terrorism frames a binary understanding of the social reality (freedom/terror, moderate/extremist, Baker-Beall 31) and outlines the actors enabled to speak and act in the counter-terrorism field (officials, practitioners, policy-makers, experts).

Baker-Beall takes a conceptual step further: building on the notion that the concept of terrorism is politically contested and socially constructed (Baker-Beall 8), he advances that terrorism (and counter-terrorism), in turns, constructs identities and social subjects (Baker-Beall 9). Accordingly, the language of EU’s “fight against terrorism” is shaping EU’s security actorness and the “identity of the EU” through multiple processes of othering, that is, identification and differentiation to frame “an overarching story or narrative for [its] self-understanding” (Reinke de Buitrago xxvii)[i]. Not unexpectedly, including the notion of “identity of the EU” might expose any study to criticalities: whose identity? How to trace it? Seeking well-contoured answers for these questions entails a demanding intellectual enterprise.

Baker-Beall argues that representations of identity and counter-terrorism policies stand in a co-constitutive relation through the definition of “who the terrorists are, what the terrorists want and the ways in which the terrorists differ from the actors responding to them” (Baker-Beall 29). The “terrorist” other is defined along with various “others” with which the differentiation occurs; depending on how the terrorist threat is framed, the others may be external, internal, and/or crossing the internal/external divide. In particular, the author contours the “migrant” other and the “Muslim” other as the two counterparts to the “identity of the EU,” which have been delineated via the articulation of the terrorist threat and the development of counter-terrorism practices.

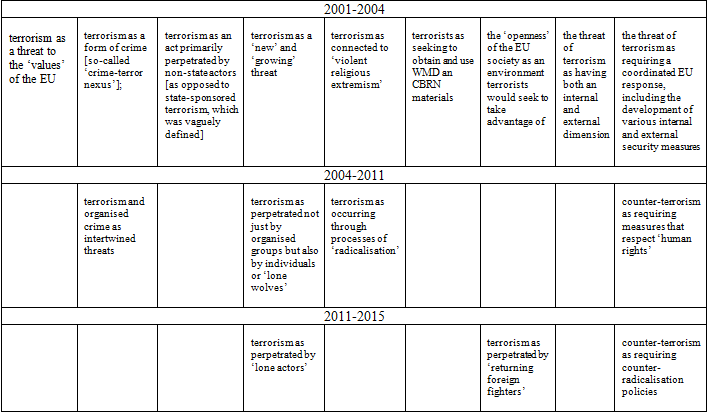

Before delving into the construction of EU’s others, imperative for structuring Baker-Beall’s argument is the genealogic reconstruction of the trajectory traversed by EU’s counter-terrorism discourse since the 1970’s. In particular, specific strands of discourse are identified throughout three crucial phases, each marked by a specific event: 2001-2004 (from the 9/11 attacks to the Madrid train bombings); 2004-2011 (Breivik’s attacks in Oslo and Utøya island); 2011-2015. It is interesting to note that some of the strands of discourse identified in one phase have ramifications in the subsequent periods, while others are confined to a certain stage (Baker-Beall 69, 75, 78).

Table 1. Strands of EU’s counter-terrorism discourse (source: Baker-Beall 2016, author’s adaptation).

These strands of discourse contributed to construct the “terrorist” other and to mould the EU as a particular type of counter-terrorist actor, one whose criminal justice-based approach seconded and complied with EU’s self-representation as a civilian and normative power. The references to “foreign fighters and returnees,” “lone actors” having travelled to “conflict areas” or attended “terrorist training camps” before returning to Europe, on the one hand, and to radicalisation, on the other, expedited the broadening of counter-terrorism to different policy fields (for example border management and visa policies) and nurtured the construction of the “migrant” other and the “Muslim” other.

The counter-terrorism discourse validates the control and surveillance of people moving across borders, conflating the figure and subjectivity of the migrant, refugee, asylum-seeker, and potential terrorist, and putting forward the idea it is exactly through the control and surveillance of border-crossers that globalised and borderless Europe is protected.

In parallel, the counter-radicalisation discourse has implied the co-optation of so-called “front-line professionals” (teachers, health and social workers, prison officers, practitioners, field experts, non-governmental and civil society organisations, victims’ groups, local authorities, law enforcement, academics), tasking them with a policing role. That may mean that control and surveillance materialise not only “at the gates” but are ubiquitous. According to the author, the prevention of violent extremism, recruitment, and mobilisation for terrorist purpose pave the way to the “securitisation of social and political life in Europe” (Baker-Beall 143) and to the “securitisation of policies designed to promote community cohesion and multi-culturalism” (Baker-Beall 165).

Accounting for the social and political implications of the counter-terrorism discourse, considering the latter not only as an instance of security policy- and practice- making, unveiling how it encroaches on non-securitarian territories are all valuable contributions to the debate and stimulating grounds on which the author builds his argument and systematises the empirical materials. The problematic point, though, is to lay the identity of the EU at the centre of his reasoning, as a monolithic entity created and recreated through EU’s counter-terrorism discourse. Whereas EU’s counter-terrorism discourse has generated the process of othering (the terrorist other, the migrant other, the Muslim other), the co-constitutive dialectics between such others and the EU identity cannot be linear and need further deconstruction. Such others are engendered through multiple trajectories of differentiations vis-à-vis plural facets representing the identity pluriverse coexisting within the EU. Even the sources of EU’s counter-terrorism discourses are not univocal, as the EU’s security field is rather multivocal and affected by inter-institutional and inter-state dynamics. In that respect, proceeding from the institutionally-codified narratives of counter-terrorism, a follow-up study on alternative strands of discourse within the EU’s archipelago, yet in a peripheral position, may be sketched by reviewing the EU’s strategic documents and pieces of legislation as well as the convoluted corpus of grey literature, transcripts, minutes, working papers issued by the whole constellation of agencies and offices etc.

The other interesting avenue for future research the author identified in the last page of the book revolves around the idea of comparing and contrasting EU’s “fight against terrorism” with the discourse about the “war on terror” and taking this research direction further to look at how different counter-terrorism discourses have emerged through processes of diffusion and counter-diffusion – adoption, adaption, resistance, and rejection of different international actors’ security models in Europe and beyond.

Reviewed by Alessandra Russo, Sciences Po Bordeaux

The European Union’s Fight Against Terrorism. Discourse: Policies and Identity

by Christopher Baker-Beall

Publisher: Manchester University Press

Hardcover / 216 pages / 2016

ISBN: 978-0-7190-9106-3

References:

Baker-Beall C. 2016. The European Union’s Fight Against Terrorism. Discourse, Policies and Identity. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Council of the EU – Press Releases and Statements. 2016. “Directive on combatting terrorism: Council confirms agreement with Parliament”. Press Release, 5 December.

Council of the EU – Press Releases and Statements. 2017. “EU strengthens rules to prevent new forms of terrorism”. Press Release, 7 March.

EUROPOL – Newsroom. 2016. “211 terrorist attacks carried out in EU Member States in 2015, new Europol report reveals”. Press Release, 20 July.

Reinke de Buitrago S. 2012. “Introduction: Othering in International Relations: Significance and Implications”. In Portraying the Other in International Relations: Cases of Othering, Their Dynamics and the Potential for Transformation, edited by Sybille Reinke de Buitrago, xiii-xxv. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Wendt A. 1994. “Collective Identity Formation and the International State”. The American Political Science Review 88(2), 384-396

[i] Othering positions the Self in a sort of continuum “from conceiving the other as anathema to the self to conceiving it as an extension of the self” (Wendt 1994, 386).

Published on November 2, 2017.