This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

My first reaction to this book was to like it very much. My second reaction was to feel quite critical, as a number of questions emerged and went unaddressed. Ultimately, I concluded that the book, while rich in historical and ethnographic detail, is actually rather thin on analysis.

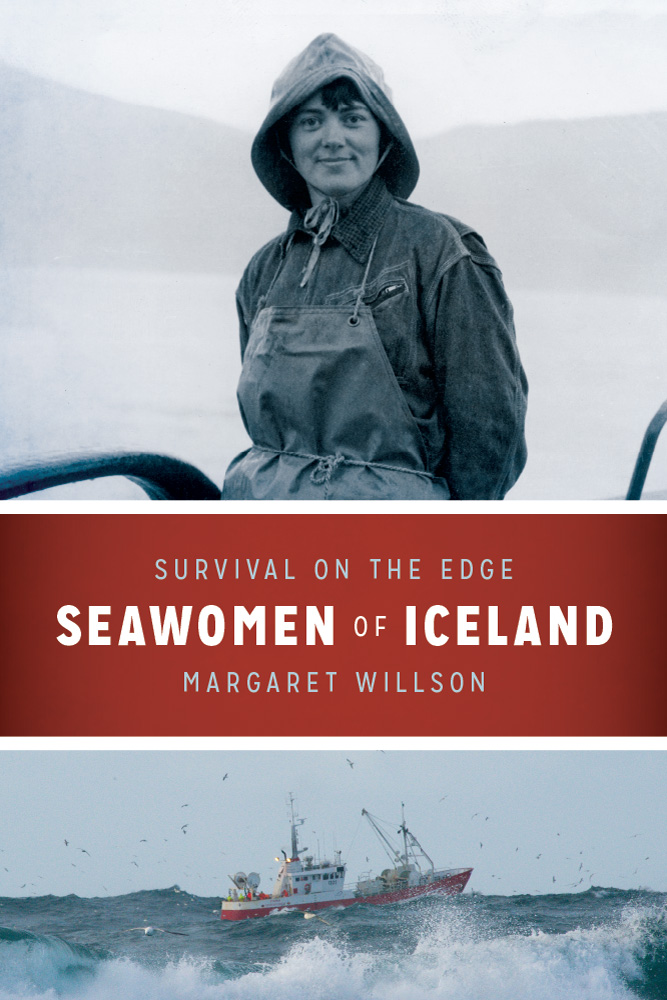

Willson’s volume is well-written, mostly clear, and follows an intriguing puzzle: it seems that Icelandic women have a long history of going to sea, but the Icelandic public is largely unaware of this. Why? What has happened to the memory and the awareness of Icelandic women’s participation in the nation’s fishing history? Once the author begins to explore this question, she has little difficulty uncovering extensive archival and oral history evidence of women in the fishery. Moreover, we learn that maritime women’s numbers now are actually increasing, so this public silence seems like a genuinely odd erasure.

An accidental encounter takes her to this mystery: she finds a small, broken-down hut with a plaque explaining that it once belonged to “one of Iceland’s greatest fishing captains,” a woman who lived from 1777 to 1863 (6). But her initial enquiries about this woman and about other Icelandic fisherwomen initially meet with blank looks and confessions of bafflement. No one seems to know that women went (or go) to sea, so she sets out to find both the history and the contemporary situation of women in the nation’s fishery. She learns that until the nineteenth century, Icelandic investment in fishing and fisheries technology had actually been quite low, even backward compared to that of other North Atlantic countries: “While countries in mainland Europe were using sails and even steam trawlers, the Icelanders had still used mostly rowboats” (84). Unlike their counterparts in the mainland countries, however, Icelandic women went to sea, being “strong members of the fishing fleet…” (84). The domestic division of labor was not strongly differentiated by sex and women’s work in both farming and fishing was essential for household survival. What changed? Not surprisingly, Willson finds that both social and technological transformations are implicated.

As occupants of a lava-based, largely treeless island marooned in the North Atlantic, Icelanders have always needed fish. Arable farming and animal husbandry are difficult, the season short, the winds brutal. Nonetheless, the author tells us that until the 1930s, “most Icelanders lived on farms.” The conditions of farming were harsh, not just because of the latitude, the rocky soils and the climate, but because of the structural inequality built into Icelandic society. From medieval times, landownership was heavily concentrated. From the fourteenth until the early twentieth century, when Iceland won its independence, the island’s Danish masters controlled trade and starvation was a not infrequent threat. Wilson tells us that “Landowners, clergy and Danish merchants formed a tiny elite all made rich off the labors of the rest of the population, who for centuries were kept in a state of abject poverty and near starvation,” managed through a “system of enforced farm servitude that lasted until 1894” (27). High infant mortality rates and stringent laws linking marriage and landownership kept the population low. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, it seems, fishing provided some relief and women played key roles as crew and even as boat captains.

When in the late nineteenth century the fishery began to modernize, however, with larger, more commercially viable boats and harbors constructed to house them, the inshore subsistence fishery shrank and women became more directly involved with fish processing, as opposed to fish catching. Simultaneously, the gendered division of labor in rural households became more distinct, and domestic duties became women’s primary role. I was particularly fascinated by the chapter on “Hags, Trolls and Whores,” which describes how, in contrast to just a few decades earlier, the beginning of the twentieth century saw seawomen talked about in derogatory terms: “strong and independent women are unacceptably unfeminine” (97). Scottish fishwives were similarly denigrated as brash and unwomanly.

To probe the question of how women’s historical role as fishers has become obscured in modern Icelandic consciousness, Wilson consulted archives, which proved astonishingly rich in information on early Icelandic seawomen, who hunted not only for fish but for seals, as well. She also traveled through the country with local guides who took her to remote fishing “outstations,” and spent time in more modern fishing towns (many built only a century ago). Her interviews with contemporary fisherwomen reveal that the late twentieth century actually saw a rise in women’s participation in the offshore industry, yet just a few years later, women were seemingly “pushed away from the sea” (151) and “fishing is currently characterized as an endeavor solely for men…” (152). Immediately after making this statement, however, Willson refers to informants who told her that more women were attending the Schools of Marine Engineering and Navigation and, moreover, that the prejudice against seawomen had diminished.

Willson does not attempt to resolve this contradiction. She concludes that while bias against women at sea may have lessened within places such as the School of Navigation, Icelandic society now consigns fishing itself to a kind of romantic backwater, an occupation incompatible with modernity. Combined with an anti-feminist backlash that values female beauty and sexuality over women’s economic contributions, this new view of fishing, she claims, accounts for the fact that few people seem aware that women have gone and still go to sea. To my mind, this is not enough to explain the erasure of seawomen’s work from the public eye. In Scotland, for example, women’s contributions to the fishery (which in the past were marked as unfeminine) are now celebrated in fisheries museums and fisherwomen’s images are deployed as heritage icons marking tourist trails.

Willson furthermore strikingly fails to ground her work within the existing—and substantial—fisheries and gender literature. Like the Icelanders unaware of their own women’s contributions to the fishery, she seems unaware that the transformations and activities she describes are found elsewhere and that consulting the cross-cultural literature might be helpful in teasing out the significance of what she observes. For example, Sally Cole’s (1991) work on Portuguese women fishers also demonstrates a shift from sea work to shore work (and a concomitant decline in married women’s personal autonomy) that would provide a very useful parallel for Willson to consider. Or she could use the work of Charlene Allison on women skippers in Washington State (1988). Allison talks about how fisher women in the Pacific Northwest love fishing in much the same way that Willson’s Icelandic women do. She does refer to New England’s Linda Greenlaw, made famous by the 1997 film, The Perfect Storm, and also the author of several books on maritime life, but mistakenly identifies her as a shark fisher, rather than a swordboat captain.

I find it genuinely strange that she does not avail herself of the rich, cross-cultural material on gender and the fisheries that reveal women of many Atlantic societies as active participants in the work of fishing, both on and offshore. Had she done so, she would have seen that the effects of technological modernization and the influence of capital investment in fishing upon women’s labor were not unique to Iceland. From North America to Europe, fishery-related activities have provided women with income and a valued place in their communities. It is important to give Iceland a context.

Reviewed by Jane Nadel-Klein, Trinity College

Seawomen of Iceland: Survival on the Edge

by Margaret Willson

Publisher: University of Washington Press

Hardcover / 312 pages / 2016

ISBN: 9780295995502