This is part of our special feature Governing the Migration Crisis.

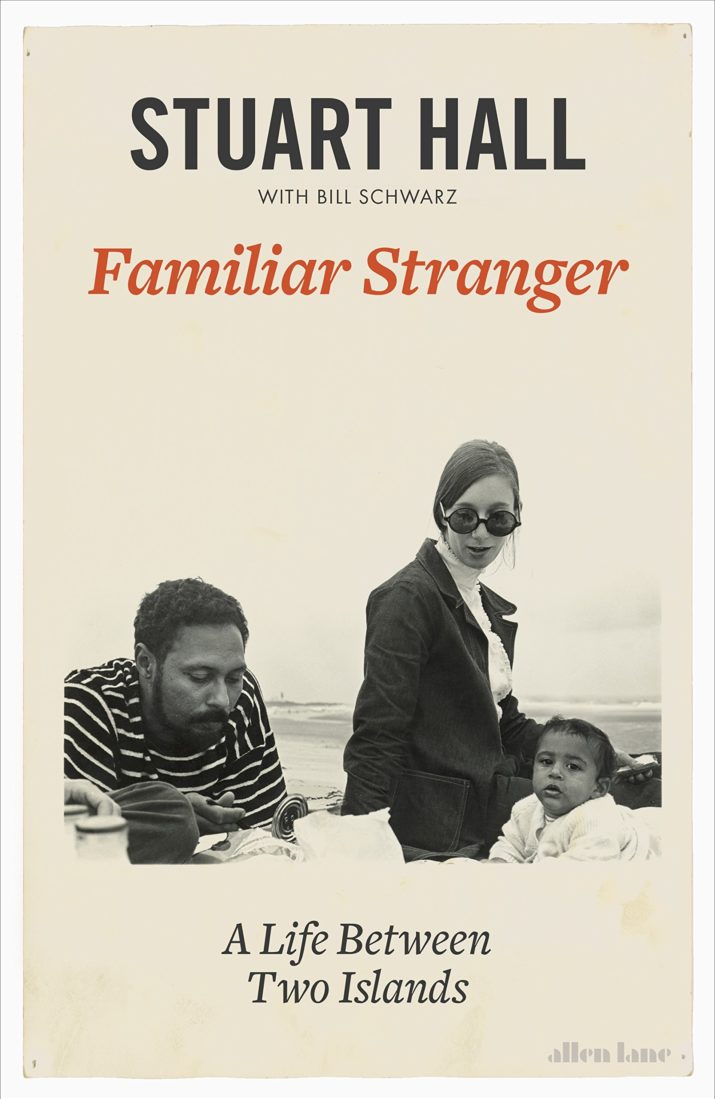

In his Preface to this memoir of Stuart Hall’s life, Bill Schwarz explains that the volume is the outcome of a collaboration between Stuart Hall and himself that goes back some twenty years. Originally initiated to fulfill a publishing contract to provide a “short manuscript in the form of a conversation seeking to illuminate the major contours” of Stuart Hall’s intellectual life, it grew and grew as Hall revised and added material; at the time of his death in February, 2014, the manuscript was over 300,000 words. What we have in Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands is only a portion of this, organized, curated, and edited by Bill Schwartz after Hall had gone. As Schwartz notes, the finished product is based on “original transcribed interviews; on Hall’s subsequent revisions;” on the “many enlargements, in various states of completion;” and “on scores of discussions and conversations spanning nearly two decades.” Some parts, says Schwartz, are “verbatim, while many others have been constructed from fragments.” Schwartz has served his collaborator wonderfully well; what we hear is unmistakably Hall’s voice, albeit often in a register that is very different to the register we would recognize from Hall’s theoretical work.

Familiar Stranger is divided into four parts, and they take us from Hall’s childhood up to the point when he moves to Birmingham and the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies in 1964. Part One, “Jamaica,” deals with Hall’s upbringing in a colored middle-class family in Kingston, Jamaica, embedded in a suffocating, genteel, colonialism. There was another Jamaica, the “darker,” nativist and potentially nationalist, street culture he could only observe from the outside, and while it might be tempting to imagine that provided some kind of antidote to the accommodated colonialism of his family, this was not to be the case. It was, however, a trigger for an interest in Jamaican culture, and for thinking historically about the Caribbean, that was to develop much later, after he had left the island. Parts Two (“Leaving Jamaica”) and Three (“Journey to Illusion”) deal with his departure from Jamaica and his migration to England, and with his experience as a student at Oxford. Migration at that time, he notes, still carried “the promise of that it would level the colonial playing field,” but of course that promise was not fulfilled. Hall outlines the conflicting tendencies of recognition, confusion, and alienation that he experienced at the social level; the intellectual formations which attracted him as he worked at finding himself within his new context; and his dealing with the racism that grew steadily in England over these years. Gradually, he established an identity that was formed in opposition to colonialism and the imperial center, and which affirmed his West Indian, Caribbean roots. He describes this as his “rebirth,” “as a diasporic subject.”

Part Four, “Transition Zone,” perhaps will most interest those who have read and benefited from Hall’s writings over the years, as it delves into the complex mix of intellectual formations and political allegiances that formed him over what were particularly turbulent years from the mid-1950s up until his move to Birmingham in 1964. These were the years of the Suez crisis, the Russian invasion of Hungary, the Aldermaston “Ban the Bomb” marches, the rise of the CND, and the establishment of, first, the Universities and New Left Review, and later, New Left Review. Hall’s account places him as primarily a political actor over this period, with his academic career largely set to one side. The intellectual formations he describes were not so much about articulating the field of study which would become Cultural Studies, but about appropriately framing the politics required by the Left at that conjuncture (there is a chapter devoted to his political development). Along the way, however, he became a very skilled “practical reader of England, of Englishness,” and this “tactic of survival” eventually “took him to the intellectual motivations of what was becoming Cultural Studies.” He talks of the importance of certain kinds of literary criticism – Leavism, for instance, and the Cambridge school of “practical criticism” – in developing this skill, as well as the centrality of his engagement with debates over the political and intellectual positions that were contested by the various components of the New Left at the time. (He also explains, at some length, what interested him so much about the subject of his graduate studies – Henry James.). Indeed, the emergence of the interests that were to feed into Cultural Studies seems closely related to Hall’s rejection of the inwardness and cultural conservatism of the New Left in Britain, and his attraction to a “more expansive conception of the domain of the political.”

For anyone familiar with Hall’s work, this is an extremely rich and fascinating memoir. Its attractions are many but its focus on Hall’s diasporic identity is of particular interest. Critics of Hall’s early writings complained about the invisibility of race in this theoretical work, implying he needed to do more in that area. The publication of Policing the Crisis made such claims redundant, but it is true that it was possible to read Hall’s work at that time and not be aware of his race or ethnicity. Indeed, Hall comments in this book that, even at the time of writing, he was still likely to meet younger scholars who were surprised to find that he was black. The centrality of race, of colonialism, and Familiar Stranger’s account of the forces which go make a diasporic intellectual will, I think, fill out a lot of the gaps in readers” conceptions of Stuart Hall.

There is, of course, the interest that any memoir is likely to generate – the performance of the person beneath the known work. And this memoir does provide a certain amount of detail about the personal interactions that have been among the stories (or perhaps more correctly, the academic gossip) about the rise of Cultural Studies for many years; so, for instance, there is discussion of the breakdown of his relationship with E.P.Thompson, and a particularly warm acknowledgement of Raymond Williams. At moments, too, we hear a much more frankly personal tone that we would have encountered in Hall’s writings before: his personal views on his encounters with V.S. Naipaul at Oxford are trenchant and uncompromising.

Apart from a fulsome tribute to his wife, Catherine Hall, and a short account of their courtship and marriage, as well as numerous acknowledgements of the kindness of those who befriended and supported him over this period of his life, however, it is not a memoir that spends much time on personal or domestic relationships. Instead, the primary task undertaken in Familiar Stranger is, in the end, one of intensely thoughtful theoretical introspection, an introspection that is directed at understanding the processes of cultural and intellectual self-fashioning that had gone into the formation of one of the most influential intellectuals of his generation.

Reviewed by Graeme Turner, The University of Queensland

Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands

by Stuart Hall, with Bill Schwartz

Publisher: Duke University Press

Hardcover / 302 pages / 2017

ISBN: 978-0-8223-6387-3

Published on October 2, 2017.