This is part of our special feature The Gender of Power.

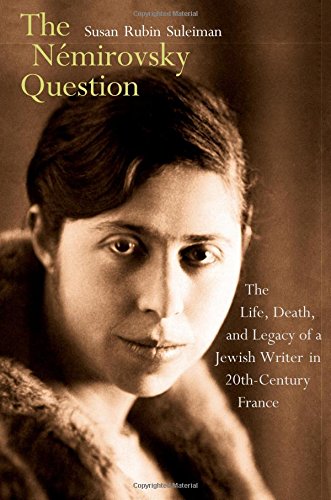

Susan Suleiman’s The Némirovsky Question: The Life, Death and Legacy of a Jewish Writer in 20th Century France is a beautiful homage to her subject, Irène Némirovsky, a brilliant femme de lettres in inter-war France whose life was brutally cut short by the Holocaust. It is also a critical study of Némirovsky’s complicated relationship to Jewishness and the impact of that legacy on her descendants.

Today, Irène Némirovsky is best known for her posthumously published novel Suite Française, which won a top prize for fiction, the Prix Renaudot in 2004, sixty-two years after her death in Auschwitz. The novel, written during the last two years of Némirovsky’s life, lay in manuscript form in a suitcase for decades before her daughters realized it was not a diary, but rather a work of literary fiction. While they transcribed and typed the manuscript as early as the 1970s, it was not until 2004 that the book was published to immediate critical acclaim. It was that critical acclaim—in addition to receiving the Prix Renaudot (the book was translated into dozens of languages and became an international best-seller) that led to the re-publication of Némirovsky’s earlier fiction, and in turn, to the current controversy regarding both her literary portrayals of Jews and certain details of her own career and life-choices.

Suleiman’s book is divided into three sections. The first, “Irène,” chronicles Némirovsky’s life, the second, “Fictions,” analyzes her Jewish-themed fiction, and the third “Denise and Elisabeth,” focuses on the lives of her orphaned daughters, as well as their children’s attempts to come to terms with Némirovsky’s legacy and their own Jewish heritage. In addition to being an analysis of Némirovsky’s literary works and personal letters, Suleiman’s book is also based on archival research and twenty interviews, half of them with Némirovsky’s descendants.

Suleiman frames Némirovsky’s life in terms of choices, which serves as an excellent device to counter a simplistic understanding that some critics have put forth of the author as a “self-hating Jew,” whose primary objective was to assimilate into French high society and leave her Russian Jewish roots behind. In fact, as Suleiman’s narrative demonstrates, in both her educational, literary, and romantic choices, Némirovsky cultivated her status of being “between languages and cultures.”(185) The daughter of wealthy Russian Jews who fled the country after the Bolshevik revolution, Némirovsky arrived in France at the age of fifteen and wrote exclusively in French. She chose to study Russian and comparative literature at the Sorbonne, however, and many of her novels and short stories center on Russian exiles—both Jewish and Gentile—and their feelings of alienation and displacement in France. Némirovsky’s choice of a fellow Russian Jewish émigré as a spouse, Suleiman points out, was not “the most strategic one”(57) for someone who aspired to assimilate into French bourgeois society. In contrast to a number of other Jewish women in the 1920s who married prominent French writers, Némirovsky rather chose a partner who shared her cultural background, and functioned as a “helpmate and supporter, never a rival for the limelight.” (57)

One of Némirovsky’s choices that contemporary critics have the most difficulty with is that of her literary collaboration with Gringoire, a widely read Parisian newspaper best know as a virulently antisemitic, collaborationist organ during the war years. Knowing that the paper did not begin to develop this orientation until 1934 helps us to understand why Némirovsky published there in the early 30s, but it is more difficult to understand why she continued to do so late into the decade and beyond. Suleiman convincingly argues that Némirovsky’s choice was over-determined. While political obliviousness, desire to be a part of the French literary establishment at all cost, and lack of solidarity with the less fortunate Jewish immigrants that the paper railed against all played a role, so too did financial incentive: both the Epstein and Némirovsky families lost their fortunes in the crash of 1929, and Némirovsky’s diaries reveal the enormous financial pressure she felt to maintain the lifestyle to which she and her husband—who, she reported in her diaries, spent twice as much as he earned— were accustomed. This financial incentive became even stronger under the occupation, when her husband was dismissed from his job at the bank and the family was completely dependent on her writing income. Ironically, despite the virulent antisemitic vitriol published in the paper, Gringoire’s editor, Horace de Carbuccia, rather astonishingly continued to publish Némirovsky’s work—under a pseudonym after the passage of the Statut des Juifs in October of 1940 prevented her from publishing in her own name—until February of 1942.

Another of Némirovsky’s problematic choices that Suleiman explores with great finesse is her decision to convert (along with Michel and her daughters) to Catholicism in February of 1939. The date suggests that she was simply trying to protect herself and her family, as we now know, in vein. Suleiman rather locates this choice within the larger nexus of a wave of conversions of secular Jewish intellectuals to Catholicism in the interwar years. For these Jews—among them the writer Jean-Jacques Bernard, who was her personal friend and converted in 1943—a genuine sense of spiritual longing could not be filled by Judaism, a religion that they had, in fact, never practiced. Suleiman ends this chapter by citing Jonathan Weiss’ observation that it was around the time of Némirovsky’s conversion that she began focusing most intensely on the problem of Jewish identity in Europe.[1] Némirovsky was not alone on this seemingly contradictory path; in fact, many Jewish converts to Catholicism in interwar France maintained a sense of ethnic Jewish identity and feeling of connectedness to their Jewish roots.[2]

Suleiman’s account also sheds light on the unfortunate choice of Irène and Michel to put off applying for French citizenship until 1932. At the suggestion of her publisher, Némirovsky initially filed an application for citizenship in 1930, so that David Golder would be eligible for the Prix Goncourt, which, at that time, was restricted to French nationals. At the last minute, however, Némirovsky decided to withdraw her application: she did not want to become French for self-serving, practical purposes, she explained in a letter to her publisher, but rather purely for love of her adopted country. While French citizenship was no guarantee of survival for Jews during the War years, the odds of being deported for foreign Jews was four times higher than for French nationals (94). Through the retrospective, these odds naturally lead us to speculate on what might have been had Némirovsky not made such a noble gesture towards a country that so cruelly betrayed her in the end.

The last of Némirovsky’s choices was her decision to neither cross over into the unoccupied zone, nor even to go into hiding. Financial considerations provide part of the answer: Némirovsky’s journals reveal that she was concerned that moving into the unoccupied zone would make communication with her publisher more difficult, and the family was completely dependent on her publishing income at this point. Ultimately, however, as Suleiman’s account makes clear, this final, fatal choice can be understood as the logical outcome of Némirovsky’s entire life experience and understanding of her place in the world. Her privileged background and pre-war status as a literary sensation gave her a false sense of security, and prevented her, more so than most other Jews, from seeing the proverbial writing on the wall until it was too late.

Némirovsky’s breakout novel, which catapulted her to literary stardom in 1930, was David Golder. The story of a Russian-Jew who sacrifices himself on the altar of capitalism to his egotistical, money-hungry wife and daughter, has been read by some—both in Némirovsky’s day and our own—as the work of a self-hating “Jewish antisemite.” Suleiman rejects this reading of the novel and of Némirovsky’s Jewish theme fiction more generally, and her succinct discussions of the concepts of both “the Jewish question” and “the self-hating Jew” serve as excellent frames for her analysis. Furthermore, Suleiman very helpfully frames her study with a discussion of the thorny issue of stigmatized minority groups and self-representation more broadly. Suleiman’s discussion of “the Jewish Question” in interwar France, by contrast, is the weakest link in her narrative. Just as her characterization of Jewish immigrants to France as mostly “poor and Yiddish speaking” fails to convey the actual diversity of the Jewish immigrant population, so too does her contention that all “Israélites” (native-born French Jews) considered the influx of foreign Jewish immigrants to France a problem. While most immigrants were of a lower socio-economic class than native-born French Jews, the majority were skilled workers, and there were also significant number of students, artists, intellectuals, and professionals among them.[3] Conversely, while many native-born French Jews did see the immigrants as a problem, for others they were a source of inspiration and a conduit into reconnecting with Judaism and Jewish culture. It is also important to point out that neither Némirovsky’s ambivalent portrayal of Jewish characters nor the controversy surrounding them in inter-war France were a unique phenomenon. Rather, Némirovsky was but one of a number of Jewish writers in the interwar years who produced fiction that other Jews found problematic, and debate of this new body of literature was an important theme in Jewish literary and associational life of the period.[4] Taking the complexity of Jewish life in interwar France better into account would have strengthened Suleiman’s contextualization of Némirovsky’s Jewish theme fiction and reactions to it.

In contrast with non-Jewish French writers of her day whose fiction also put forth stereotyped, Jewish characters that many found offensive, Suleiman notes, “in Némirovsky’s world, the Jewish other is contrasted not with the French same but with other Jewish others: rich versus poor, assimilated versus “ethnic,” dog versus wolf.” (142) This is a key insight that succinctly captures Suleiman’s understanding of Némirovsky’s literature and general frame of mind vis-à-vis her Jewish background. For Suleiman, Némirovsky was very much writing from the Jewish perspective of someone for whom—through no fault of her own—Jewishness had almost no positive content. Furthermore, Suleiman argues, while Némirovsky sought acceptance within the French literary establishment, she never attempted to hide either her Jewishness or her foreignness in order to do so. Rather, her “preferred position” was the “in-between, the position of emotional ambivalence and of an existential sense of otherness in relation to French or any other national or ethnic identity.” (191) Suleiman’s explanation of the ostensible lack of Jewish characters in Suite Française follows this line of analysis. As Suleiman sees it, by the time that Némirovsky, living a stigmatized existence as a Jew in occupied France, was writing her final novel she could no longer place “Jews” and “the French” on the same mental and literary page. There is a Jewish character in the novel, Suleiman explains, and that character is Némirovsky herself, the omniscient narrator, who observes and often offers biting satire of a society of which could no long aspire to be a part.

While Jewishness is a difficult inheritance for all child Holocaust survivors, it was particularly complicated for Denise and Elisabeth. Growing up in the shadow of their once famous mother’s dubious choices and deeply ambivalent relationship with Jewishness, the sisters’ paths in this regard initially diverged quite markedly. Denise raised her children as Catholics and told them nothing of their Jewish background until they were young adults, while Elisabeth rejected Catholicism at a young age and married a fellow atheist, but began to “feel a genuine continuity”(243) with her parents’ heritage after the birth of her children. By the ends of their lives, both sisters were living openly as secular Jews and today, they lie together in the family tomb in the Jewish section of the Belleville cemetery. Suleiman’s narrative also follows the life-stories of Denise and Elisabeth’s children and grandchildren, and considers the role that both Némirovsky’s literary revival and the family’s Jewish heritage have played in the lives and mental landscapes of her descendants. None are practicing Jews, nor affiliated with a Jewish community of any sort. All feel a strong sense of duty to stand up to antisemitism and intolerance of all kind.

In her conclusion, Suleiman commendably counters an inaccurate portrait that one finds all too often in the American Jewish media of France as a hotbed of antisemitism from which Jews are fleeing in droves for Israel. Rather, Suleiman underlines the enormous differences between the current situation and that of the 1930s, and rightly notes that vast majority of French Jew are staying in France. One can only second the “fervent hope” with which she closes this passionate, nuanced, and deeply insightful book: that history will not repeat itself “for Jews or other vulnerable minorities,” and, in turn, that Jews will “be able to continue asking themselves, and each other, the endless questions that have characterized Jewish existence for centuries.”(292)

Reviewed by Nadia Malinovich, Université de Picardie Jules Verne

The Némirovsky Question: The Life, Death and Legacy of a Jewish Writer in 20th Century France

by Susan Rubin Suleiman

Publisher: Yale University Press

Hardcover / 357 pages / 2016

ISBN 9780300171969

References:

[1] Jonathan Weiss, Irène Némirovsky: Her Life and Works (Stanford University Press, 2006).

[2] On this phenomenon, see Frédéric Gugelot, “De Ratisbonne à Lustiger : Les Convertis à l’époque contemporaine,” Archives juives , 35/1 (2002), and Nadia Malinovich, French and Jewish: Culture and the Politics of Identity in Early Twentieth-Century France (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2008; 158-161.

[3] See Nancy Green, The Pletzl of Paris: Jewish Immigrant Workers in the Belle Epoque (New York: Homes and Meier, 1986); 111-113 and Malinovich, French and Jewish; 108-115.

[4] This Jewish cultural flowering of the 1920s is the subject of French and Jewish.

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on July 6, 2017