Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, the ongoing emergence of a new, multi-faceted European identity has been a gradual process. In a valuable contribution, this book takes stock of a work-in-process after its first quarter century, the melting pot fusion that is Europe, as reflected (but not in a vulgar Marxist sense) in European cinema. The geopolitical situation is encapsulated in a compelling formulation: “Europe is a borderless internal space that is also closed around its edges” (140). Euro-Visions devotes just under half its space to what (from a Film Studies perspective) is crucial background information, effectively to a primer in European Studies. It also traces milestones in EU cultural policies, and in the European film industry and its financing. One example: in 2014 the funding program MEDIA, which supported many of the films foregrounded here and which is profiled alongside Eurimages (37), was superseded by Creative Europe, operating across the arts. The broad context provided by Mariana Liz then underpins a succession of individual film analyses in the remainder of the book, with film choices being largely persuasive.

In a sense, this book takes up where another left off, Pierre Sorlin’s European Cinemas, European Societies, 1939-1990.[i] The latter was an early attempt at a convergence sought by Mariana Liz, but it was the exception, with much of the relevant literature long in thrall to a notion of European cinema as the sum of national cinema movements. The fall of the Wall opened a Pandora’s box of identity issues. Here, these are generally negotiated with clarity, but also with occasional essentialism, even when that accords with institutional self-image: “Quality and mobility are key aspects of the idea of Europe that are also visible in contemporary European cinema” (14). The conclusion reached in a 2009 book titled European Identity[ii] was that “at the level of mass society, “European” often means little else than the geographic expansion of a specific national identity – a supranational nationalism – onto European beaches and into European soccer arenas.” Or, to take up the first example cited by Mariana Liz, an expansion onto the stage of Eurovision song contests, a truly puzzling phenomenon, given that this year’s featured an Australian among the finalists… The notion of the transnational and/or transcultural does progress faltering advances on nationalism, and Liz addresses this to some degree, too.

Discussion of European heritage film introduces a number of mini-analyses of recent examples, starting with Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003). While the historical periods treated in these films inevitably extend well beyond the production timeframe of “contemporary cinema,” to cite the book’s subtitle, the author’s own historical frame of reference is at times too limited. In itself, the following passage is unproblematic: “In the first decade of the 2000s, a series of films emerged that explored issues such as collaboration and resistance. In doing so, many of these films challenge the notions of history and memory, as well as the official narrative of an integrated European past” (81). But neither these films nor these themes emerged as a new phenomenon, and a question not addressed here is how this body of films related to earlier European cinema, albeit in national garb. In the early 70s, films by Louis Malle and Marcel Ophüls spawned a lengthy debate about official narratives in France, while Bertolucci’s Conformist among others explored Italian variations on these European themes. Black Book, discussed on page 85ff, almost demands to be profiled against Fassbinder’s Lili Marleen, as does 12:08 East of Bucharest (99ff) against Bertolucci’s Spider’s Stratagem. Does Europe, and especially Germany, now have a “normalized” status which explains the absence in Liz’ book of an earlier debate around “aestheticizing Fascism,” featuring names such as Saul Friedländer and Susan Sontag? Further historical specificity of European film and memory issues in the twenty-first century would have sharpened the argument advanced here and found subsequent historical inflections to earlier issues.

This critique extends to analyses of individual films, going beyond the concrete case cited. In Bellocchio’s Buongiorno, Notte (Good Morning, Night, 2003), Liz rightly signals that the interplay between archival and fictional images, almost the signature of this director, suggests counterfactual histories, and lends the film a traumatic quality. But she does not go on to examine how stylistically suited that blend might be to conveying both national and European collective memory/memories. There is no mention here of any links between an ongoing, hallowed Resistance tradition and postwar Italian communism, nor of the latter’s stance towards the Red Brigades who kidnapped and murdered Aldo Moro. But this minefield of continuities and discontinuities is important for understanding “a European history apparently nationally specific in content, but significant across the continent” (95), and it is precisely this interplay that is embedded in the film. In a crucial scene, a Partisan text is sung to a Russian melody, while Verdi’s triumphal march from Aïda appears in the background after about two minutes of the film (as one of the brigadists paces out their new hideout), but then again much later over footage of Stalin. Altogether, the soundtrack of much European cinema poses further question marks. Woody Allen’s Match Point is addressed at the visual level in an otherwise enlightening section on ‘cinematic postcards’ from major European cities. But the prominent soundtrack of this film is dominated by Italian opera, pointing viewers in directions other than London as tourist destination. To return to Bellocchio, still more suggestive for the topic of Liz’ book are images from Rossellini’s iconic Paisà (1946), showing the murder of Resistance fighters, to viewers whose historical position reassures them of the sense of this sacrifice. I understand Bellocchio’s film reference less as “images from her [the female brigadist’s] ‘actual’ dreams” (92), and rather as the bold gesture of citing film history as history, as Italian and European history. Fassbinder adopted this technique at a stage when German history left him few other options. Europe’s history can also be approached through contemporary cinema when the latter draws on its own history, the history of film culture.

In her Conclusion, Mariana Liz finds the “meaning” of Europe “within three major oppositions (…): national versus transnational, art versus commerce and thought versus emotion” (143). Of these, the second is a topos of the history of cinema and is probably over-emphasized, while the first has the most current thrust but is under-developed. While relevant films are discussed briefly, the overall implications of this “opposition” warranted further synthesis of their narrative strands. (The index gives but two page references for “transnational cinema,” and none for ‘cinéma beur’.) Fatih Akin is mentioned, but otherwise Turkish-German cinema is largely unexplored, all the more striking when one considers the significance for Mariana Liz’ topic of the hyphenated “-German” component. For this Germany is the old/new fusion of Cold War enemies, a geographical unity seeking to submerge pre-1990 national identity/identities in more than just a European passport. It subsequently acquired a degree of normalization as symbolized by initially hesitant fans waving German flags at the 2006 soccer world championship, its venue, the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, evoking a very different stage of European history. In this new Federal Republic the significant population of Turkish background was alien to the East Germans, whose own identity of the preceding three decades left few traces in the new entity… This panoramic overview is important even for what is more than a mere detail in Paris, a film made two years after the 2006 World Cup by a filmmaker who elsewhere often fails to delve below the surface, Cédric Klapisch. Liz documents: “The film shows him [an illegal migrant from Cameroon to France] working at a holiday resort in Africa and wearing a French national team football T-shirt with Zidane’s name on it” (126). Greater postcolonial abjection is hard to imagine: Cameroon was frequently a finalist (but not in 2006); Zidane, the French captain, was famously red-carded for headbutting an opponent in the final.

Europe will continue to evolve in directions not always anticipated. Post-dating this book, new identity challenges arising from Brexit face British filmmakers, as well as European citizens. The ongoing importance of Liz’ topic remains guaranteed. It is to be hoped that her economical, often insightful work spawns a whole series of complementary monographs.

Reviewed by Roger Hillman, Australian National University

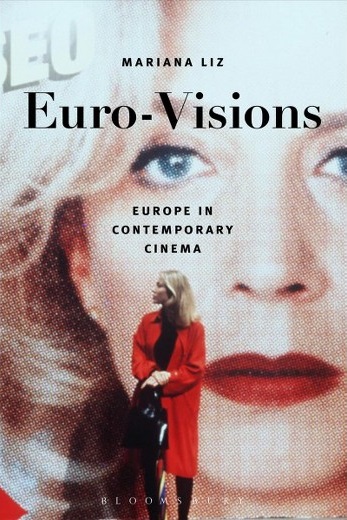

Euro-Visions: Europe in Contemporary Cinema

by Mariana Liz

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Paperback / 200 pages / 2016

ISBN 978-0822363323

To read more book reviews, please click here.

Published on June 20, 2017

References:

[i] Sorlin, Pierre, 1991. European Cinemas, European Societies, 1939-1990, London and New York: Routledge.

[ii] Jeffrey T. Checkel and Peter J. Katzenstein (eds.), 2009. European Identity, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 214.